Orthostatic intolerance in a 16-year-old girl

What is the cause of extreme fatigue, nausea and presyncope in a 16-year-old girl whose ECG shows nonspecific ST changes?

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a syndrome of orthostatic intolerance accompanied by symptoms such as faintness, nausea, fatigue and headache.

- POTS commonly occurs after a viral infection, postpartum or after an illness, but it may occur spontaneously.

- About 85% of cases of POTS occur in women, most often aged 15 to 50 years.

- Mild cases may go undiagnosed and it is open to misdiagnosis because POTS is not well known.

- POTS usually resolves over months, but in its more severe form, it may persist for many months to years.

- Treatment is primarily supportive with increasing dietary salt and fluid intake, elevating the head of the bed and avoiding lying down too much.

The extreme fatigue that Kylie was experiencing did not improve with rest or sleep and worsened with any exertion, even walking across a room. Such slight exertion, especially standing still for a couple of minutes, produced faintness, nausea and palpitations (regular, at about 100 beats per minute [bpm], when tapped out). Kylie lost 2kg in weight over six weeks because she did not feel like eating, and if she forced herself to eat, she became nauseated. There was no further fever, no chest pain or heaviness in the chest and no shortness of breath (but a feeling of needing to breathe deeply and rest when she exerted herself).

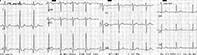

Kylie was on no medications and had no past medical problems. There was no family history of any cardiac disorder, mental illness or asthma. Kylie saw her GP again five weeks after she first became sick. Her ECG is shown in the Figure.

Q1. What does this ECG show?

The ECG shows a sinus rhythm, rate 90bpm and regular, and nonspecific ST changes in the limb leads inferiorly. These suggest early repolarisation (a high take-off of the ST segment).

Q2. What is POTS?

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is due to an abnormality in the regulation of the autonomic nervous system, in particular the neural mediation of the cardiovascular system. The heart is usually structurally normal. The main sign of this syndrome is orthostatic intolerance (hypotension and tachycardia). The condition may be severe enough to produce syncope even on standing for a short time only.

There are often other autonomic features such as nausea, generalised mild abdominal discomfort, generalised mild headache especially when standing, facial pallor and cool, pale extremities. The upright position may cause mottled venous discolouration in the lower limbs that reverses upon lying down.

POTS commonly occurs after a viral infection, postpartum or after an illness during which the patient has been largely bed bound, but it may occur spontaneously. It is difficult to estimate the incidence of this condition as there are variations in its presentation. Mild cases may go undiagnosed and it is open to misdiagnosis because the condition is not well known and the differential diagnosis is broad.

About 85% of cases of POTS occur in women, most often in those aged 15 to 50 years. It usually resolves over months, but in its more severe, incapacitating form, it may persist for many months to years, and the incidence of this severe form ranges from one in thousands to one in hundreds of thousands annually. It is very likely that some cases of chronic fatigue syndrome are due to POTS.

Q3. How is POTS diagnosed?

POTS is diagnosed by its clinical features and the exclusion of other diagnoses. A full clinical examination is important. Orthostatic intolerance is confirmed by an increase in heart rate of at least 30bpm on standing in adults (or 40bpm in adolescents) or an increase to 120bpm or faster during the first 10 minutes of standing, accompanied by orthostatic symptoms (headache, hypotension, nausea, faintness, pallor).

Normally, people have a mild increase in heart rate upon standing (10 to 15bpm) and a mild decrease in blood pressure (5 to 10mmHg, from lying to standing). These findings stabilise over about a minute. ‘Neurally-mediated hypotension’ is defined as a drop in systolic blood pressure of 25mmHg from lying to standing (or if a tilt test is positive) and it is further confirmation of POTS. Blood tests (e.g. full blood count; urea, creatinine and electrolytes; liver function tests; C-reactive protein; blood glucose, antinuclear antibody, thyroid-stimulating hormone; and iron studies) are usually performed to exclude anaemia, systemic lupus erythematosus and thyroid, renal and hepatic diseases. An ECG is recommended; if it is abnormal, an echocardiogram and cardiology review should be arranged urgently.

Q4. What is the cause of POTS?

The cause of POTS is not clear but is thought to be due to dysautonomia. As it is a syndrome, by definition, it is a cluster of signs and symptoms rather than a well-defined disease. There is evidence of sympathetic nervous system over-activation (raised serum noradrenaline levels in research subjects).1 Of note, this differs from repeated neurocardiogenic presyncope (also called vasovagal presyncope), in which serum noradrenaline levels are low.2 There is also evidence of small fibre neuropathy affecting the sudomotor nerves in 50% of patients.1 The significance of these findings with respect to prognosis is uncertain. There is evidence of a familial tendency to the condition and there are specific genes that have been associated with the syndrome. There are also a wide number of other conditions that present possible differential diagnoses and increase the likelihood statistically that an individual will also suffer from POTS. The more common of these are listed in the Box.1

Q5. Has POTS got a psychiatric component to it?

POTS is not considered to be a psychiatric or psychological condition. Due to its uncertain prognosis, physically unpleasant symptoms, functional impairment and often prolonged course, it may precipitate generalised anxiety or major depression in susceptible individuals. Surprisingly, the incidence of these comorbidities is the same as in the general population.1 The stress of performing simple everyday activities should not be underestimated. Family, friends and teachers may often become frustrated that the patient is not improving or be overly encouraging about what the patient might be able to do; these reactions may increase stress or worsen mood in the affected individual.

Q6. What exacerbates symptoms?

Symptoms are more marked when standing upright. Mild exertion may paradoxically relieve the faintness associated with standing still, but physical weakness and fatigue will become more prominent. Causes of vasodilation, notably warmth, exacerbate the tachycardia and hypotension. Diversion of blood to the intestine during digestion may exacerbate symptoms, including nausea. Fear and anxiety, such as that associated with upcoming exams or witnessing an accident, may also increase symptoms. Dehydration and hypoglycaemia may complicate the condition and its signs.

Q7. How is POTS treated?

Managing any underlying contributory causes is important. A high salt intake (3 to 10g daily) together with increased hydration may improve intravascular hydration and reduce symptom severity. Maintaining an upright posture, rather than taking to bed for hours, is important, and tilting the head of the bed up is recommended. Compression stockings may help. Exercise should be performed frequently for short periods of time (even if only for several minutes) as tolerated. It is likely that the patient will not be able to perform significant aerobic exercise or prolonged exertion, unless it can be done in a recumbent position (e.g. swimming or rowing). Eating small amounts frequently is recommended and a multivitamin could be considered if intake is insufficient. Some patients have been trialled on fludrocortisone, serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with varying success.1

Outcome

Kylie’s blood tests were normal. The GP had a phone consultation with the cardiologist who reported the ECG, and it was decided that echocardiography was not indicated. Kylie, through sheer determination, continued to attend school as normal but was exempt from doing sport. Special consideration was granted for examinations and she was given extra time to study and prepare. This greatly reduced her stress levels. Kylie followed medical advice and found a high salt intake to be most useful in taking the edge off her faintness on standing. After two months, on some days she felt less affected, and by four months, she felt almost completely better performing ordinary simple activities. Even so, she still experienced faintness and nausea if she overexerted herself physically or if she had a lot of things to do. CT

References

Further reading