Innocence revisited – 11

This month we arrive at the eventual outcome of all medical interventions – death.

Compiled by Dr John Ellard

Exodus

First, your Editor – still wrestling with the problems of that night, so many decades ago, at Sydney’s Royal North Shore Hospital.

A gentleman lay dying in the medical ward. There was little more to do: he was unconscious but his family had come in multitudes to comfort him and each other by their presence and concern. Not even a consultant thanatologist could do more.

To view my patient I had to thread my way through unyielding rows of backs, whose owners saw further medical intervention as a disruption of their grief. I found that my resources extended to penetrating three or four ranks and then standing on tip-toe to peer at him from afar, at the same time listening to the sound of his breathing to reassure myself that he was still among us.

This occasional and remote surveillance continued until for some reason or another, early one morning, the family retreated to form a scrum outside, and I could have a good look.

Two things became apparent. The sound of breathing was the sound of the oxygen bubbles from a nasal catheter stirring up the secretions in the pharynx, and my patient was not only dead, but icy cold. The news was conveyed to the scrum, and after order was restored I left the nurses to their last duties.

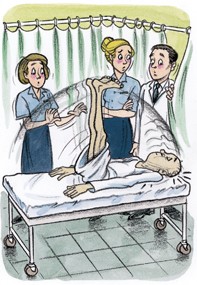

I was puzzled when they called me back. Nothing was said, and I was taken behind the screens to where he was being laid out. He was sitting bolt upright. Silence still reigned, although I must confess that I felt the need to speak. Then the two nurses holding his legs down slowly relaxed their efforts, allowing his legs to rise in the air, while his torso lay gently back. A brief hesitation, and then renewed pressure on his legs slowly rose him up again. Rigor mortis I could understand – but what to do?

We thought for a while, and then installed him in a wheelchair, with a sheet roping him to its back, and his legs, suitably draped, sticking out in front of him.

The night porter was summoned, calmed, and then he, the nurse, the chair and its occupant set out into the darkness for the mortuary, all three of them looking rigidly in front, as though afraid of what they might see were they to look sideways.

The medical giants’ omission

Next, Dr Robert N. Linacre, who had some trouble calling his shots:

About my third night – why do these things always happen after dark? – of pretending to be ward intern, I thought I’d better check on a patient on the private floor.

I’d been told about her. This octogenarian had been admitted earlier in the day with the largest in a series of myocardial infarcts and wasn’t doing too well. Her wise physician had instructed that she be made comfortable and left to slip quietly away from this world. She was rather VIP; the mother both of a local dignitary and one of the hospital’s more important charge sisters.

Paying my respects seemed quite in order. I could make a succinct note in the record to demonstrate my mature medical judgement, and, if I played it right, I might get a cup of tea and be able to park my overloaded white coat for a moment.

My coat was weighed down with a heavy-duty stethoscope which was guaranteed to produce murmurs on demand and which, at a pinch, could be used to bang in tent pegs. The right-hand pocket contained four heavy volumes, explaining what to do in cases of emergencies related to medicine, paediatrics, ENT and podiatry; the left pocket covered the remaining specialties in a kilo or two.

In the private room, lights subdued and the standard issue of flowers scattered around, the old lady sat in state in her bed, puffing through lightly smiling, pursed lips, rather like a duchess nonplussed after running for a bus. Her pearls jiggled up and down in time to her JVP. Her delicate cyanosis matched the Liberty print of her night attire. Gathered around her were a dozen assorted affluent relatives, including the superior Sister.

I spoke one or two learned platitudes – after all, even the aforementioned wise physician couldn’t last forever, and a chap might need to set up practice sometime – took the lady’s pulse, and turned to leave.

Hang on – I couldn’t feel a pulse.

Frantic unprofessional massaging of her radial artery confirmed that it had gone. She was very quiet. Even the puffing had stopped. She seemed quite a lot bluer. These changes had been noticed by the daughter-Sister, who started to massage the other radial artery.

Our eyes met. Pause. A sophisticated, casual grope at the carotid pulse. Nothing. Pause. Meet the Sister’s eyes over the bed. Pause. Weak smile from me. ‘Ahem.’ Pause. Remassage of patient’s wrist.

‘I’m very sorry to have to tell you that your dear old relative has, well, passed away.’

The dozen relatives collapse in a rather unmiddle class wail. The Sister and I smile at each other for support, let down the head of the bed to stop the old dear’s head rolling quite so obscenely, shut her eyes, and herd the wailing mob down to a sort of waiting room.

Cups of tea and cuddles all round. I look up the Woodchuck Instant Guide to Mourning and think that they seem to have traversed the initial denial stage surprisingly smoothly, and I decide to escape before they reach the anger/hostility stages. Better make those notices I was planning to do.

While trying to compose these remarks so that they didn’t end up with, ‘I hereby declare, with the powers invested in me, this patient well and truly dead’, a nurse, all startled doe, comes to the desk – ‘Would you come, quickly’.

The light in the room was on. The old lady was puffing away rather less smoothly than before, her cyanosis now exceeded the Liberty print, and the pearls were jammed up to her ear lobes by her JVP.

She didn’t seem terribly dead. Not very well, certainly, but equally, not very dead. Not dead enough for my liking anyway.

There was absolutely nothing in the library of books I was carrying to help in the situation. To the distinguished writers, death had seemed sort of, well, permanent. The problem of patients who vacillate or compromise appeared to be one that the medical giants had neglected.

I felt bloody stupid. Far from confusing left hemiblock from axis perambulation I couldn’t even tell dead from alive! Six long years and an Honours degree. All blown in a few seconds.

This agonising was interrupted by the super-Sister saying that the relatives felt a little better, thank you, and would like to go home after paying their last respects.

Oh, sure. The old lady would like that. At the moment she was sitting up in bed, stronger than ever, asking to read the paper!

I explained that we would need a few minutes to get things suitably arranged. As the minutes passed I grew to resent the old lady’s increasing ruddy good health, and the relatives’ increasing impatience. After 10 minutes the Sister took me aside and demanded to know what was going on. Having received my feeble explanation and a mumble about the well-recognised problems of Stokes–Adams syndrome, she inspected the body and agreed that life was not altogether extinct.

By half-an-hour even the grief-stricken relatives knew that something was up.

My little speech about the dramatic change in the patient’s state was not one of my great moments. It was pathetic. There is really surprisingly little one can say on such an occasion. They all filed back in to the room to stare at the cadaver who, by this time, was sitting up in bed, fumbling with the television programs. I fled, feeling that I had little to contribute further.

She died, quietly and permanently, in her sleep later that night.

A terrible mistake?

And last, Dr David Cooke, who will never know whether or not he should resist temptation again:

She was terribly, terribly thin, and she was the only patient who ever offered to pay me for my services with her emaciated body. This last fact is more an indictment of my personal attractiveness than a comment on my strict professional rectitude. She offered it with a grin, rather like a cheeky but likeable child. Oddly innocent.

I learnt that she was a cheerful and unrepentant alcoholic, getting through a flagon of cheap red and a bottle of brandy every day. She earned enough to keep alive by acting as a door-to-door collector for a popular charity – one reason why doorknock appeals leave me cold.

She lived with her second husband, also an alcoholic, in a room rented from her first spouse, and I wonder now why I never asked her how she paid the rent. It was a gloomy, gruesome place, with guilt and deprivation written everywhere in grime.

I treated her once for pneumonia. She had no fever, only a hacking cough which rattled her bones and threatened to part her fragile soul from what was left of her body. In hospital, with antibiotics, she recovered. A small and inconsiderable bill to me remained unpaid, and eventually unnoticed.

About the same time I had a patient who had won a racehorse in a raffle. If you believed the raffle organiser, the colt would have left Phar Lap anchored, but his performance on the track was disappointing.

I was invited to a local race meeting to see the colt in action. Now, I am not a punter. I will admit to a liking for strong drink occasionally and in good company, but betting is not my scene, as they say. But on this rare occasion I strolled around the betting ring and tried to look knowledgeable.

She was there. She spotted me, and said, ‘Fancy seeing you here’, with that grin. I forget what I replied.

Some time after this I received a call from her daughter to come urgently. Mum was desperately ill. I asked for a brief history, and was told that she had had a recurrence of chest trouble and had seen another doctor who had found the absence of fever reassuring. Perhaps he did not understand pneumonia in alcoholics.

I called around to the house and entered the depressing bedroom to find my patient dead. The second husband was absent. I declined to give a death certificate and rang the police. I remember a padlock on the telephone.

I went home only to have a second call – this time from the second husband. In a desperate but controlled voice he said, ‘Doctor, I’m afraid you’ve made a terrible mistake. My wife is not dead. She’s terribly ill, but she’s not dead’.

I went out again, bewildered and curious, and was shown at once into the now familiar sleazy bedroom.

She was dead, very dead. I told the stricken family that this time there could be no doubt and then, after chatting to a tolerant police sergeant, gave a certificate, listing the causes of death as pneumonia, malnutrition and alcoholism.

I often wonder if shame at catching her at the races had played a part in her calling in my colleague. Or maybe I should have accepted payment in kind. After all, aren’t the wishes of the patient always paramount?