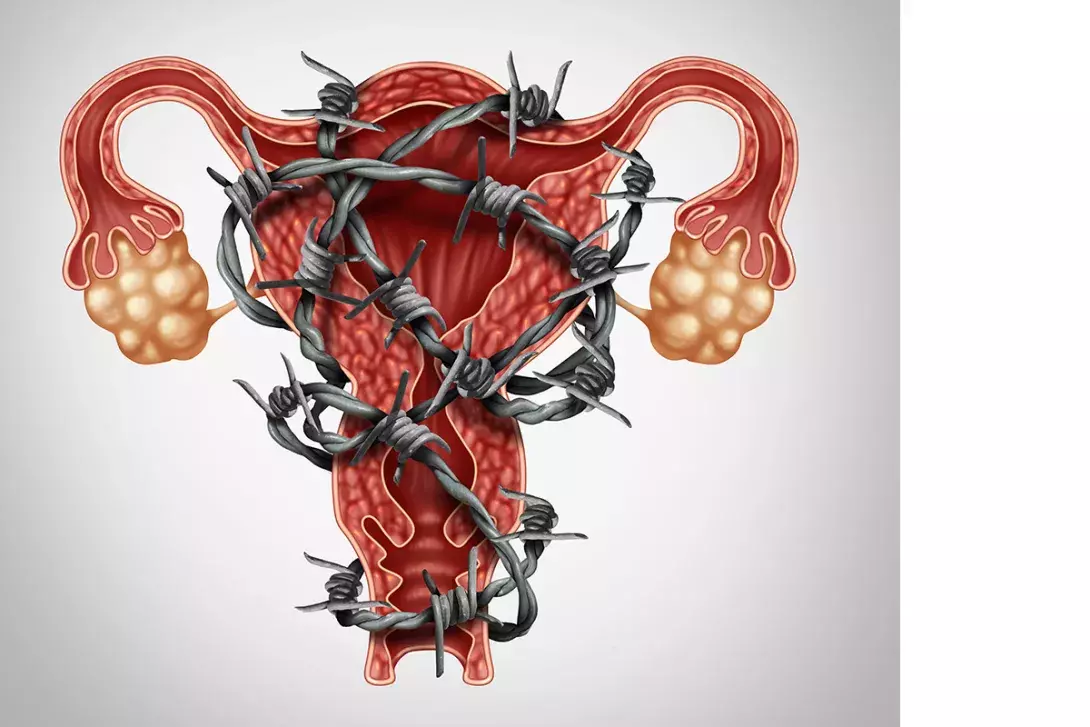

Endometriosis – current management options

Endometriosis is the most common cause of persistent pelvic pain in women. Any age group can be affected. Initial medical management of painful symptoms without invasive diagnosis is appropriate.

Endometriosis, or the presence of endometrium-like glands and stroma outside the endometrial cavity, is the most common but not sole cause of persistent pelvic pain in women of reproductive age. Endometriosis is often under-recognised, and diagnostic delay may have a substantial impact on quality of life. Recent Australian data on a large cohort of women followed up over 20 years show an endometriosis prevalence of 11.4%, suggesting that more than 830,000 Australian women and girls are living with endometriosis.1 The causes of endometriosis remain unclear; however genetic factors are considered to account for 50% of causation, with biological and environmental factors contributing to the other 50%.2

Clearly, a surgical procedure is required to satisfy the definition and confirm a diagnosis of endometriosis. However, a clinical diagnosis without surgery is reasonable when history, examination and imaging findings suggest endometriosis is likely. Importantly, many other persistent pelvic pain conditions have similar management strategies to endometriosis. An initial discussion about differential diagnoses and options for management is appropriate and may help reduce morbidity.

This article summarises the steps to diagnosis and management of women with endometriosis. Resources on endometriosis for GPs and patients, including webinars on awareness, diagnosis, treatment, complementary medicine and fertility, are available from Endometriosis Australia (www.endometriosisaustralia.org/webinars).

History taking

To determine a potential diagnosis of endometriosis, initial questions should be directed towards:

- pain and systemic symptoms

- infertility.

No single symptom or sign is either sensitive or specific enough for the diagnosis of endometriosis, but clusters of symptoms in the history increase the likelihood of this diagnosis (Box). Endometriosis is present in around half of women presenting with infertility (see below). Adolescents can and do get endometriosis, and young age does not exclude the diagnosis.

Imaging

With advances in imaging, particularly ultrasound examination, around half of people with endometriosis can be diagnosed sonographically. Importantly, this group often represents the more severe cases with deep lesions in the ovaries or pelvic tissues that are discernible by ultrasound examination (Figure 1). Earlier diagnosis of endometriosis may reduce progression, although this has not been established with any certainty. However, early lesions cannot be reliably identified using any type of imaging. MRI may be useful in certain situations but should not be used as a primary tool in general practice in Australia. It is particularly limited by cost.

When endometriosis is suspected, a good-quality two-dimensional ultrasound scan is an appropriate first step. This should be performed transvaginally in women who are sexually active. A transabdominal scan should be performed in those who are not sexually active but has less capacity to diagnose endometriosis accurately.

There has been considerable discussion about the use of deeply invasive endometriosis (DIE) scans. These are specialist ultrasound scans that use additional manoeuvres to image the uterosacral ligaments, the pelvic spaces to check for mobility, and the rectum to assess size, depth and attachment of endometriosis lesions. DIE scans have variable availability, found predominantly in major cities, and may be costly.

Key to a DIE scan is the dynamic nature of ultrasound and its capacity to see organs move relative to each other. In endometriosis, inflammation often results in the formation of adhesions, which restrict movement between organs. Clinicians should be aware of the ‘sliding sign’ in ultrasound reports, which is said to be positive when organs slide well over each other (i.e. the rectum over the posterior uterus or the bladder over the anterior uterus). A negative sliding sign may indicate adhesion of organs due to scar tissue formation and more advanced disease.

The other major advantage of DIE ultrasound is the ability to define lesions within the bowel or urinary tract. This is generally for surgical planning. When there is disease in these organs, specialist involvement is recommended.

There is no role for serum marker tests in the diagnosis of endometriosis at this time.3 They should not be routinely requested.

Medical management

For women presenting with pain associated with menstruation, intercourse or bowel or bladder function, the first step is to exclude acute or life-threatening conditions, such as infection or a pregnancy-related issue. After this, endometriosis is a principal differential diagnosis. However, dysmenorrhoea is common, affecting about 50% of women and girls with each cycle, and although 10% of women and girls will have endometriosis in the course of their lifetime, 90% will not. Thus it is clear that most cases of dysmenorrhoea are not related to endometriosis.

Symptom treatment

Treatment of dysmenorrhoea should be symptom-based, with use of NSAIDs, simple analgesics and heat each being supported by evidence. Local heat, commonly baths, showers or a hot water bottle, can be helpful. Clinicians should warn of the risk of burns to the lower abdomen with prolonged use of hot water bottles, leading to skin discolouration. General advice about exercise, diet and self-care is appropriate. Importantly, regular review (annually after symptoms are stabilised) is necessary to ensure that symptoms are under control.

Menstrual regulation and suppression

If symptoms continue or progress or cause time to be missed from school, work or family and social life, or there are constitutional symptoms then both further investigation and treatment are warranted. Pelvic ultrasound examination may help differentiate contributors to pelvic pain. Even in the absence of any pathology seen on ultrasound examination, symptomatic treatment is recommended. Menstrual regulation and suppression should be offered.

Oral contraceptive pill

Menstrual regulation and suppression will often be in the form of an oral contraceptive pill (OCP), although they are not specifically licensed for endometriosis management. Mechanisms whereby an OCP can be effective for treating endometriosis are shown in Figure 2. When an OCP is used continuously (without taking the placebo pills in a monophasic preparation), menstruation as well as ovulation is suppressed, further decreasing noxious stimuli. The fewer cycles and more quiescent the ovaries and uterus, the fewer pain symptoms.

OCPs can have side effects, with breakthrough bleeding common when they are taken continuously. Discussion about this and a plan of management are appropriate.

Progestogens

Progesterone alone in various forms has also been shown to be effective for the treatment of endometriosis symptoms. Oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) and dienogest are both registered to treat endometriosis in Australia. MPA is listed on the PBS and is therefore cheaper for patients when used long term. Neither is approved as a contraceptive, and this should be considered in discussions with the patient.

The higher-dose (52 mg) levonorgestrel intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) has been shown to have efficacy in treating the symptoms of endometriosis but is not registered for this purpose in Australia, although it is registered for contraception. No data are available for the low-dose (19.5 mg) LNG-IUD at this time.

Progestogens have a more variable effect on ovulation than the OCP, with some such as the LNG-IUD and oral intermittent MPA suppressing some but not all ovulatory cycles. Depot MPA (a registered contraceptive) and dienogest have a more reliable ovulatory suppressant effect. Side effects, including irregular vaginal bleeding, mood lability, depression and androgenic symptoms (acne, hair loss, weight gain), may limit tolerability. Progesterone resistance may contribute to a limited effect or no effect in some people with endometriosis.

Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonists

Complete ovulatory suppression using a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist, such as monthly depot injections of goserelin acetate, may be helpful in a minority of people with endometriosis. This treatment should be initiated only by a gynaecologist but can be continued in conjunction with the GP. The complete suppression of oestrogen limits the duration of action, with only six months of treatment currently registered for use in Australia to treat endometriosis. Menopausal-like side effects (hot flushes, vaginal dryness, skin change and bone density decrease) are all common with this medication. It may be used with add-back oestrogen (commonly the OCP), with no decrease in action.

The GnRH antagonist elagolix is an oral, daily preparation with a similar side effect profile to the GnRH agonists. It is not currently available in Australia but may become available in the future.

Surgical treatment

Surgical removal of endometriosis lesions should decrease symptoms and improve fertility (see below) but is not as straightforward as it seems. Placebo-controlled surgical studies have shown that there is a benefit of surgical treatment for symptoms, with 80% of patients having a response.4 This means that one in five women who have surgery do not benefit. The flipside of these studies is that the placebo group had a 30% response rate – also not unusual in any type of intervention.

Generally, most surgical procedures for endometriosis are performed by laparoscopy in Australia. The improved visualisation, shorter recovery time and other surgical benefits compared with laparotomy are well studied. Laparoscopy allows systematic examination of the entire peritoneal cavity, from the diaphragm to the pelvic floor, where the vast majority of endometriosis lesions are located.

Excision versus ablation

The modality of surgical removal has been hotly debated, with excision reported to be superior to ablation.5 However, it is the removal of the lesions that is important, including the glandular and stromal elements, surrounding neoangiogenesis and fibrotic ingrowths (Figure 3). The depth of lesion is crucial, and flexibility as to modality is the key. Surgeons dealing with endometriosis should be able perform both dissection and excision around key structures and remove all disease but also be able to ablate (or more accurately vaporise) superficial lesions. They should know when and how to use these different modalities.

Decision-making about the timing of surgery should be shared. Generally, medical treatments should be offered and tried initially. There is no role for ‘diagnostic laparoscopy’ in modern endometriosis management. Any time surgery is recommended, it should be with the view to both making the diagnosis and providing surgical treatment at the same surgical procedure.

Symptom improvement after surgery

Among people who have surgery, symptoms recur in 30 to 50% within five years.6 Given that the underlying aetiology of endometriosis remains unknown but may include genetic factors that are not modified by the surgical technique, this might be expected. Postoperative ovarian or menstrual suppression may delay recurrence of symptoms.

Although repeat surgical intervention is common, there is substantial risk with multiple repeated procedures. Surgery may directly cause central sensitisation and nociception. As surgical interventions can have a placebo response, the key to decision-making about a repeat procedure is the response to the initial procedure and its durability. A few months’ symptom response is not an adequate response, and a few years’ response should be the minimum criterion for surgical success.

Fertility

About one-third of people with endometriosis have fertility concerns. Although endometriosis is a common diagnosis in women being investigated for infertility, there still remains no clear mechanism for the effect, which can occur with even minimal disease. Treatments are few in this situation, with hormonal medical managements contraindicated as they interfere with ovulation or fertilisation. The only choices are expectant management (which should be first line), surgery or assisted reproductive technology (usually in vitro fertilisation [IVF]).

As a general principle, if expectant management has been unsuccessful, and the woman has no other symptoms, IVF is a prudent choice. For a woman with other symptoms of endometriosis, consideration of surgery (as long as it is the first surgical procedure) may be offered to diminish both symptoms and improve the chance of pregnancy. Fertility is generally possible, with 70 to 80% of women becoming pregnant following IVF or surgery. This is less than in the population who do not have endometriosis. Specific groups (i.e. those whose fallopian tubes and ovaries are particularly involved in the endometriosis process) have a poor outcome with either surgery or IVF.

There are many permutations and details to be considered in decision-making about treatment options for women with fertility concerns. Patient preference and provision of appropriate information by an infertility expert should inform the choice.

Conclusion

Often, the earliest symptoms of endometriosis are a constellation of problems around menstruation. For anyone presenting with these symptoms, treatment with NSAIDs, simple analgesics and local heat, general advice and follow-up are appropriate. Persistent problems should be investigated, with ultrasound examination as a firstline investigation, and endometriosis and other possible diagnoses should be discussed with the patient. Simple hormonal treatments should be considered and offered. Patients with ongoing symptoms or ovarian or other pelvic pathology seen on imaging should be referred for specialist input. Surgery should be used judiciously, and the adage that ‘the first go is the best go’ kept in mind. Fertility problems affect one in three women with endometriosis. There are few choices for managing this, with surgery or IVF the only alternatives to expectant management. Practice points are listed here. MT