Pelvic venous disorders. Embracing the new SVP classification

Syndromic terminology for pelvic venous disorders, such as May-Thurner, nutcracker or pelvic congestion syndromes, should be abandoned and the new symptoms-varices-pathophysiology (SVP) classification embraced. This will help avoid confusion and allow clinicians to categorise these diverse patient populations into more homogeneous groups, enabling better comparisons, data analysis and treatment guidelines.

- The pelvic veins are interconnected with the lower limb veins. Pelvic venous disorders can thus cause a diverse range of symptoms, affecting the pelvis or the lower limbs.

- Symptoms of pelvic venous disorders are reproducible and related to gravity and exercise and relieved by rest.

- Pelvic venous compression and reflux are widely prevalent in the general population and symptom expression is not well understood.

- Syndromic terminology should be abandoned in favour of the more concise SVP classification, which links symptoms, anatomy and pathophysiology and gives clinicians and patients a common platform for understanding and formulating management plans.

- Patients with pelvic venous disorders that are considered clinically relevant can be treated safely and effectively with minimally invasive options.

Over the past decade, increasing research on the pelvic veins has improved our understanding of how they relate to acute and chronic venous disease. Our ability to treat these veins with minimally invasive techniques has also grown exponentially. However, traditional syndromic terminology, such as May-Thurner, nutcracker and pelvic congestion syndromes, has made it difficult to have consistent reporting standards and outcome measures, in turn affecting the interpretation of the available literature. The lack of uniform definitions and diagnostic criteria has had a negative effect on the credibility of these syndromes, potentially resulting in patients remaining underdiagnosed and undertreated.

Anatomy and physiology of the pelvic veins

To begin to understand pelvic venous disorders and put all these syndromes together, we need to have a basic knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the region. First, the pelvic veins and lower limb veins are anatomically connected. Second, veins carry blood towards the heart and their failure to perform this physiological function leads to increased venous pressure, which in turn manifests as signs or symptoms in the pelvis or the leg. Third, blood in veins, unlike arteries, flows in both directions (antegrade or retrograde) depending on the pressure gradient; venous blood flows from high pressure to low pressure areas and this can be affected by activity levels and gravity.

The legs drain through the external iliac veins into the common iliac veins (CIVs), and link to the pelvic veins through the internal pudendal, obturator, round ligament (inguinal) and inferior gluteal veins. The pelvis drains through the internal iliac veins (IIVs) and the gonadal veins. The IIVs join the CIVs, the left gonadal vein drains into the left renal vein, and the right gonadal vein drains directly into the inferior vena cava. All pelvic veins connect through pelvic plexuses.

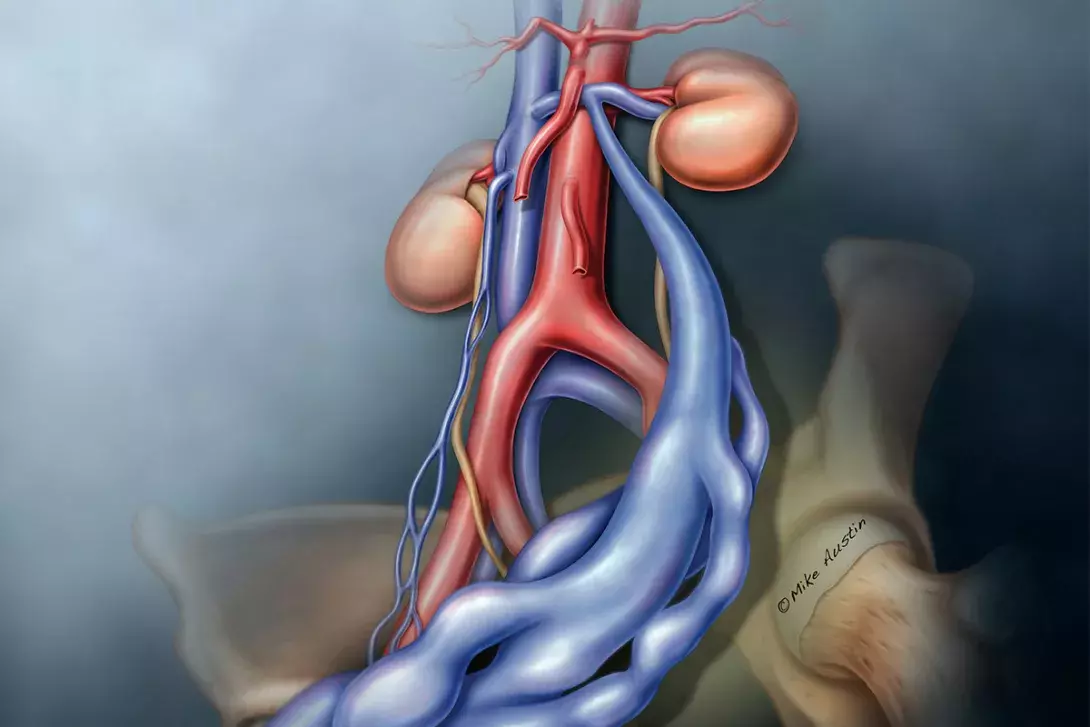

Pelvic venous disorders can arise from primary reflux or reflux secondary to obstruction.1 The new proposed classification considers the symptoms, the location of varices (abnormally dilated veins) and the pathophysiology. Primary reflux usually affects the gonadal vein (mostly in women), and obstruction usually affects the CIV or left renal vein (Figure 1).

Symptoms and signs of pelvic venous disorders

Symptoms and signs associated with pelvic venous disorders relate to venous hypertension. The location where that occurs determines the patient’s presenting symptoms. The most common presentations are:

- chronic pelvic pain

- venous claudication

- lower limb varices (typical or atypical)

- flank pain and haematuria.

It is important to note that different symptoms can come from the same vein lesions, and different lesions can cause similar symptoms.2 The anatomical findings of venous compression, with or without pelvic venous reflux, is prevalent in the general population and it is poorly understood why some patients develop symptoms, yet others do not.3,4 Ovarian vein incompetence is also a common finding after pregnancy, yet the development of symptoms is variable and poorly understood.5

Unfortunately, physicians and patients trying to make sense of these different patterns using variable syndromic terminology with different interpretation

over the years has led to confusion as there can be a disconnect between the anatomical description of a syndrome (e.g. May-Thurner syndrome) and the presence of symptoms. This disconnect further adds to confusion regarding management of these syndromes.

Syndromic terminology of pelvic venous disorders

May-Thurner syndrome (compression syndrome)

The term May-Thurner syndrome is used by some to describe the anatomical compression of the left CIV by the right CIV against the spine, without regard to symptoms. This appears widely prevalent, affecting at least a third of the population. The May-Thurner lesion is also referred to as a nonthrombotic iliac vein lesion. The term is also used by many physicians to describe the finding of an iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (DVT) with an underlying stenosis caused by that compression.

Clinically, a range of symptoms have been associated with the presence of the so-called May-Thurner anatomy as a result of the venous outflow obstruction that occurs. These symptoms can range from pelvic pain, back pain, urinary urgency, bloating, venous claudication, leg aching and swelling.

According to the initial description of this compression syndrome, it develops in three stages: stage one where the compression is dynamic and the patient asymptomatic; stage two with symptoms caused by a fixed stenosis (fibrotic scarring from repetitive trauma from the arterial pulsations); and stage three the development of an extensive iliofemoral DVT.

Confusion regarding use of May-Thurner syndrome terminology occurs as not every patient who develops a stenosis, even a severe one, develops symptoms, symptoms can vary significantly between patients, and not every patient develops a DVT. It has been proposed that pelvic vein obstruction is a permissive pathology and other triggers such as reflux, infection or immobility can turn the patient symptomatic.6

Different patients with the same degree of stenosis can be on two different ends of the spectrum, with no symptoms or very mild ones on one end and excruciating pain or nonhealing ulcers on the other. This is not dissimilar to arterial stenosis, when a patient with a severe femoral artery stenosis or even occlusion can be completely asymptomatic, and another can have severe short distance claudication or a threatened limb.

What adds to the confusion is the myriad of symptoms that patients can present with. Some patients can have venous claudication, aching and swelling if the venous pressure affects the leg, or pelvic pain if the pressure is diverted through the internal iliac vein across the other side through pelvic collaterals. Other patients might develop varices through the pelvic escape points, such as: the perineal (connecting the internal and external pudendal veins) causing inner thigh and posterior labial varicose veins; the inguinal (recanalised round ligament vein) causing groin and labial varicose veins; the gluteal giving varices around the buttocks area; or the sciatic nerve varicose veins causing neurological symptoms.

All the veins in the pelvis are interconnected like a spider web, and the development of symptoms (May-Thurner syndrome) from outflow obstruction at the level of the CIV depends on where the venous pressure is transmitted to and what venous channels open to compensate for the increased venous pressure.

Nutcracker syndrome

The term nutcracker is used to describe the compression of the left renal vein between the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta (like a nutcracker). The original description accounted for flank pain and haematuria due to the increased venous pressure into the kidney from the venous outflow obstruction.

Sometimes, the gonadal vein functions as a collateral, diverting the flow to the pelvis instead. This takes the pressure off the kidney, and the patient may not have flank pain and haematuria. Instead, the redirected venous flow through the gonadal vein can cause pelvic pain or atypical varices such as a varicocele. This is a good illustration of how the same lesion can present with different symptoms and cause confusion depending on what territory becomes exposed to increased venous pressure.

Pelvic congestion syndrome

Chronic pelvic pain is widely prevalent among women and the most common reason for referral to gynaecologists. However, a considerable proportion of these women are told that there is no explanation for their pain, and they need to learn to live with it.

About 30% of women experiencing chronic pelvic pain have pelvic congestion syndrome as the primary diagnosis for their chronic pelvic pain with another 10 to 15% having this diagnosis in conjunction with another pathology.7 The diagnosis of pelvic congestion syndrome as a cause of chronic pelvic pain is secondary only to endometriosis in prevalence.7,8 Typical symptoms of pelvic congestion include chronic pelvic pain, which is worse with menstruation, intercourse and exercise, with significant postcoital ache relieved by rest in the presence of pelvic varices.

This syndromic terminology is out-dated and confusing as there are multiple potential sources for the pelvic varices and it is the anatomical findings that dictate the correct management. If imaging shows the gonadal vein is incompetent and dilated, it could be primary reflux as shown in Figure 2. This scenario is more commonly seen in multiparous women, and a carefully selected patient will benefit from ovarian embolisation.

If the gonadal vein is incompetent and dilated as a result of left renal vein compression instead, as in nutcracker syndrome, the source of the problem is obstruction with secondary reflux. Addressing just the refluxing ovarian vein will not result in a positive outcome and can potentially compromise the kidney.

The other source of pelvic varices can be the IIV, most commonly because of left CIV obstruction, whereby there is reversal of blood flow (retrograde) through the IIV. This then acts as an outflow vessel diverting flow through pelvic collaterals towards the other side and causing pelvic venous hypertension (Figure 3).

Lastly, it is possible that the patient may have all three conditions: left renal vein compression, left CIV compression (Figure 1) and ovarian vein incompetence. It is up to a dedicated venous specialist to determine the pattern and the best way to address the issue. For example, a patient with recurrent pelvic congestion syndrome despite previous coiling of the ovarian vein, who required further ballooning and stenting of a CIV obstructive lesion is shown in Figure 4. This is another good example of how the same symptoms can be caused by different venous disorders, and the same venous disorders can cause different symptoms.

The new symptoms-varices-pathophysiology classification

Complex cases, such as those described above, are the reason venous specialists around the world are abandoning the syndromic terminology and embracing the new pelvic venous disorders classification: the symptoms-varices-pathophysiology (SVP) classification.1 This is meant to complement the widely accepted clinical etiologic anatomic physiologic (CEAP) classification. The SVP classification is patient centred: ‘S’ for symptoms guides towards the anatomical location of the varices ‘V’ and facilitates best management by including the pathophysiology ‘P’ (reflux or obstruction, thrombotic or nonthrombotic). This classification avoids confusion and allows clinicians to categorise these diverse patient populations into homogeneous groups, enabling better comparisons, data analysis and treatment guidelines, similarly to the tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) classification for cancer. A comparison of the SVP and syndromic classification systems for pelvic venous disorders is summarised in Box 1.

Role of pelvic veins and implications for management

Anatomical venous compression and reflux can occur without symptoms and can be an incidental finding in which case no treatment is needed. The role that the pelvic veins play in the development and progression of chronic venous disease, however, is becoming widely accepted. Evaluation of the whole venous system and not just the infrainguinal segment should be performed in patients presenting with signs and symptoms suggestive of pelvic venous disorders.3-5,9-18

Pelvic venous duplex ultrasound examination is appropriate as first-line imaging.16 Sometimes axial imaging with CT venography or magnetic resonance venography might be necessary. Venography and intravascular ultrasound examination are used if a decision to treat has been made with the latter considered the ‘gold standard’ in venous obstruction.17

Pelvic venous disorders can be treated with either balloon angioplasty and stenting for obstruction of the outflow tract (mainly for the iliac veins) or coiling for refluxing veins (most commonly gonadal veins) after obstruction has been ruled out. Both treatment options are minimally invasive and widely successful with minimal risk of complications.19-21

Venous stenting to treat venous obstruction is not new with the first report of venous stenting from 1995.11 However, a multitude of new dedicated devices have been made available in the past decade. The current recommendation is to treat clinically relevant obstruction if there is evidence of stenosis of at least 50%.22 Multiple societal guidelines support therapeutic option based on the robust available evidence.12-15

Obstruction as the main source of venous hypertension is now recognised as a major contributor to venous disease and its consequences. Excellent symptom improvement and ulcer healing has been reported after iliac vein stenting of outflow obstruction despite residual reflux (Figures 5a and b).23 This suggests the proximal obstructive pathology might be more important than reflux.

Which patients to refer?

The following patients should be referred to a venous specialist (Box 2).

- Patients who complain of severe pain and oedema affecting the whole leg, worse after prolonged standing and exercise, described as a ‘bursting sensation’, with no obvious dilated varices as seen in Figure 6. These patients may have significant pelvic obstruction as the source of the problem and will not benefit from isolated treatment of superficial incompetence, even if a duplex scan shows saphenous incompetence. Instead, they will benefit from balloon angioplasty and stenting of the outflow obstruction.

- Patients with advanced chronic venous disease, especially recurrent venous ulcers, should be investigated for pelvic venous disorders. They are more likely to have these disorders and to benefit from intervention, even in the presence of deep venous reflux (Figures 5a and b).

- Women with undiagnosed chronic pelvic pain that worsens with exercise and intercourse and is relieved by rest, with prolonged postcoital ache have a high chance of having a pelvic venous disorder as the main diagnosis and should be investigated and referred early to a specialist.

- People with atypical varicose veins, vulvar veins, varicocele, or aggressive recurrence of varicose veins, which also suggest the possibility of clinically relevant pelvic venous disorders.

Because of the significant variation in patient presentation and underlying pathology, clinical judgement supersedes any available guideline. As always, patient selection is the most exquisite form of medical expertise. Consideration of each individual patient’s history and examination, combined with the appropriate diagnostic imaging and a tailored interpretation of the available literature, along with patient preferences, will lead to the best outcomes. Multiple societal guidelines and other publications are available to guide physicians on patient selection and prevent under- or overtreatment.15

Conclusion

Pelvic venous disorders can cause a diverse range of symptoms affecting the pelvis and the lower limbs. Full evaluation of the venous system should include imaging of the pelvic veins, with at least a duplex ultrasound examination. Syndromic terminology should be abandoned in favour of a more concise classification that links symptoms, anatomy and pathophysiology (SVP), guiding clinicians and patients uniformly. Patients presenting with severe venous disease, recurrent venous disease or undiagnosed claudication or chronic pelvic pain should be referred to a venous specialist. Incidental findings of venous compression or reflux in asymptomatic patients with no sequelae of chronic venous hypertension do not require intervention. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Associate Professor Villalba has received consulting fees from Boston Scientific and Philips in the past but not related to this manuscript. Associate Professor Chin: None.