Innocence revisited – 8

Our series continues as we move to special examinations and tests.

Compiled by Dr John Ellard

A bootlace tackle

We all know that special diagnostic tests are done for many reasons. Most commonly the patient’s wellbeing is the sole consideration, but occasionally (whisper it) the practitioner’s anxiety, narcissism, obsessionalism or ignorance may make itself felt. Knowing this, who has not felt virtuous when abstaining from the unnecessary, or relieved when the patient recoils from conventional but marginally indicated investigative speleology, or worse?

Dr Tertius rejoiced, and fell:

It was my first practice and she was almost my first patient in this little country town. Well over eighty, she had been dying for some months, or perhaps just fading away. She also recognised my inexperience and refused to be bustled into clever diagnoses. Knowing that she hadn’t long to live she steadfastly refused to go to the nearby Base hospital for further tests. And that suited me…I hadn’t any idea at all what was really wrong, except that she was simply not going to last.

Even so, after every visit – and they were becoming daily – I was met at the door by her very alert, ninety-year-old husband. He said little, so I answered even less. Yes, his wife was comfortable and no, I didn’t think any special tests were needed or even other opinions for that matter. Surely it was better that she just died peacefully and without pain, as would obviously happen, than that she be hassled into a high-powered centre.

After the best part of two months she did, indeed, just fade away. The family were there, and they fully accepted that grandmother had died. Not her husband, however.

As I came down the front steps I saw him standing by the gate, waiting for me. In my best funereal voice, I offered my sympathy. He ignored it. Instead, he stood up to his full six-and-a-half feet, the better to look down on me.

‘You still don’t know why she died, do you?’ he accused.

I said nothing. I walked away out the gate and towards the car, nearly a hundred yards down the main street by the shops, when I realised he was following me, cane waving in the air.

‘You’re a fool of a doctor’, he yelled in his loudest voice, making sure that the neighbourhood heard, which it did.

‘You’re a fool’, he repeated, ‘you’re not a doctor’s bootlace’. I hurried, now scarlet, as fast as I could with ‘doctor’s bootlace’ echoing and being repeated time and time again. As I started the car I noticed the family, hopefully equally embarrassed, shepherding grandfather home. I also noticed that the entire village population seemed to be witness to my failing.

As I get older I often wonder just why I chased up so many degrees to go after my name – I’m sure that any good psychiatrist would read into it my absolute need to prove, at least to myself, that I was better than a ‘doctor’s bootlace’.

Sleight of hand

Tests can be recursive weapons, impaling the tester as well as the tested. As a manifestation of this capacity, Dr Pelham goes down vicariously:

It was my first week on the wards as a medical student. Every move was observed by thirty pairs of variously-ill eyes. The desire to flee those polished halls was overwhelming. Survival meant taking a grip – rather as one might turbo- charge a monkey wrench.

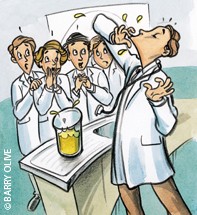

The consultant gathered us around him in the sluice, mother-hen style. A flask of cloudy, yellow urine was set before us on the stainless steel sink.

‘Diabetes’, pointed the consultant.

So that’s what it looks like, I thought.

‘Sugar in the urine’, he continued. Turning, he confronted one of my colleagues who was still swaying under the load of the night before’s hangover, and asked, ‘How would you test for this sugar, young man?’

The ‘young man’ feigned senility perfectly, unable to utter anything comprehensible.

‘Quite simple’, twinkled the consultant, ‘by taste’. So saying, he plunged a finger into the flask and, on withdrawing it, he licked it.

My unfortunate colleague did a rapid impression of a billiard table cover.

‘And now, sir’, continued the consultant, ‘you shall learn by experience and also taste it’.

Wavering as do high office blocks in times of depressed atmospheric conditions, our young man advanced and hesitantly immersed a digit into the urine and licked it.

The atmospherics plummeted – the billiard table cover became quite gaudy.

‘Observation!’ roared our cruel leader. ‘You have today learned the lesson of observation. Nothing to do with diabetes and glycosuria. Had you all been watching more closely you would have noticed that, unlike our seedy friend here, I inserted my index finger into the urine, but I licked my second finger’.

Red alert

Those who would rather not taste urine may prefer to look at it instead. Dr E.L. Sear was reluctant to do even that:

As a locum in a busy country practice, I viewed with some relief the last patient for the day.

He was a stoutly-built, healthy-looking wheat farmer, and handed me the diagnosis ‘on a plate’ – in this instance, a small jam jar containing a reddish liquid.

When he told me that for the past few days he had been passing blood in his urine, I believed him. My interrogation, such as it was, and a general physical examination, gave no clue as to the cause. Nevertheless, painless haematuria had to be taken seriously, so off he went to the district hospital, with a note.

One week later he returned – with a further note – which said, ‘We’ve done a cystoscopy and an IVP, both of which were normal. However, when further questioned, he did admit to having eaten a lot of beetroot lately…’

I glanced around the consulting room. The microscope – with its dustcover untouched – stood as mute testimony to ‘More mistakes are made by not looking than by not knowing’.

Blow me down

There can be more poignant failures, as recounted to me by a pathologist many years ago:

It was suspected that a citizen from one of the furthest and most desiccated towns in New South Wales had malaria, so his doctor despatched him to the big city to have his blood examined. In those days this meant endless hours of discomfort and boredom in a dogbox carriage hauled behind a soot-producing steam locomotive.

It was all touch and go with the all-important timing, for the sick man had to rush to the hospital, provide his specimen, and then rush back to the station to catch his train before it retraced its not very frequent meanderings to the West.

Apprised of the urgency of it all, my informant gathered up the man at the enquiries counter, conducted him through the labyrinth of corridors leading to his laboratory, made the slides, whisked him out again, and finally installed him in a taxi for the journey back to the station.

Exhausted by a work pace entirely unsuited to the temperament of pathologists, our hero wended his way back, pausing to yarn to a colleague or two, and then settled in his chair, lit his pipe, and reached for his stains.

Unfortunately, there was little for him to do except pursue the large blowfly which had beaten him to the films, both thick and thin.

I wondered what the report said, but he didn’t tell me.

Now that we have put the patients at ease, completed the physical examination and marshalled the powers of science, next month the cures can begin.