Bed 12

A GP remembers the first time she saw a hospital bed change into a person, with a family, friends and a story to tell.

We huddle around Bed 12, flimsy blue curtains drawn, a trolley of paper files piled high. It’s the morning ward round, a formalised hunger games ritual where humiliation is disguised as a learning experience, necessary to disgrace any medical student who lacks the mettle to spew out the correct answers during the bedside grilling.

The patient is a fellow in his 60s, rubbing his right thumb and forefinger endlessly while the rest of him is frozen in position, one side of his blue gown slipping off his shoulder.

I am still new to this learning exercise designed to make a public display of who knows what, who stands firm in the face of intimidation.

‘You.’

The consultant’s finger points towards me, and the colleagues on either side withdraw, relieved to be temporarily spared.

‘Look at this man’s face. What do you notice?’

I glance at the patient, his face devoid of expression, the urgent pill rolling of his thumb and finger, the only movement in the room.

‘Well, you won’t find the answer staring at your shoes.’

I realise my eyes have dropped to the floor, my heart flapping loose behind my sternum. I clear my throat and whisper. ‘He has Parkinson’s disease.’

The neurologist’s voice is low, filled with derision. ‘Is that what I asked? I want to know what you notice about his face. If you don’t look, you’ll miss things. It’s the most important part of any examination. Now use your eyes and look.’

I force myself to stare at the slight man, who gazes past us at some point in the distance, his eyes watery and unfocused. In Parkinson’s disease, there is a loss of dopamine from a part of the brain known as the basal ganglia, critical for fine tuning movement. This results in rigid, jerky movements, difficulty initiating motion and a loss of facial expression, which can be misinterpreted as aloofness or lack of engagement.

My voice falters, aware that Patient 12 is impaled on his bed by a semicircle of curious eyeballs, the hospital gown now exposing half his wrinkled chest. ‘He lacks facial expression.’

‘Thank you.’

We spend another 10 minutes discussing the pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease and why the drugs eventually cease working. Another medical student is asked to demonstrate the classical signs of this neurological condition by examining the hapless man, who is now asked to walk a short distance and turn around, his feet frozen to the floor by his depleted basal ganglia.

We move on. The registrar barks instructions at a nurse to help the man back to bed.

A few days later, he is discharged. I am sitting at the nurses’ station when he shuffles past, now dressed in jeans and a battered jacket. He stops and hands me a large brown envelope, my name on the front. I wonder how he knows my name and am ashamed when I realise, I don’t know his.

‘Take it home, love.’

Stooped and stumbling, he leaves, his son carrying a duffle bag and the discharge summary.

I shove the envelope into my backpack and forget about it, my attention absorbed by my long days, looming exams and a busy waitressing job. I find it weeks later, crumpled in the bottom of my bag. Curious, I reach in and pull out several pages of typed print, the pages blotted with whiteout.

Ronald Woods, yes that was his name, had written a narrative about his experience of living with a degenerative neurological condition. I realise he wanted me to know that he was more than his Parkinson’s, more than the patient in Bed 12 with no facial expression.

Ronald is a retired engineer, fought in Borneo in the Second World War. He is married and has three children and eight grandchildren. After diagnosis, he was forced to retire: a challenging period marked by depression.

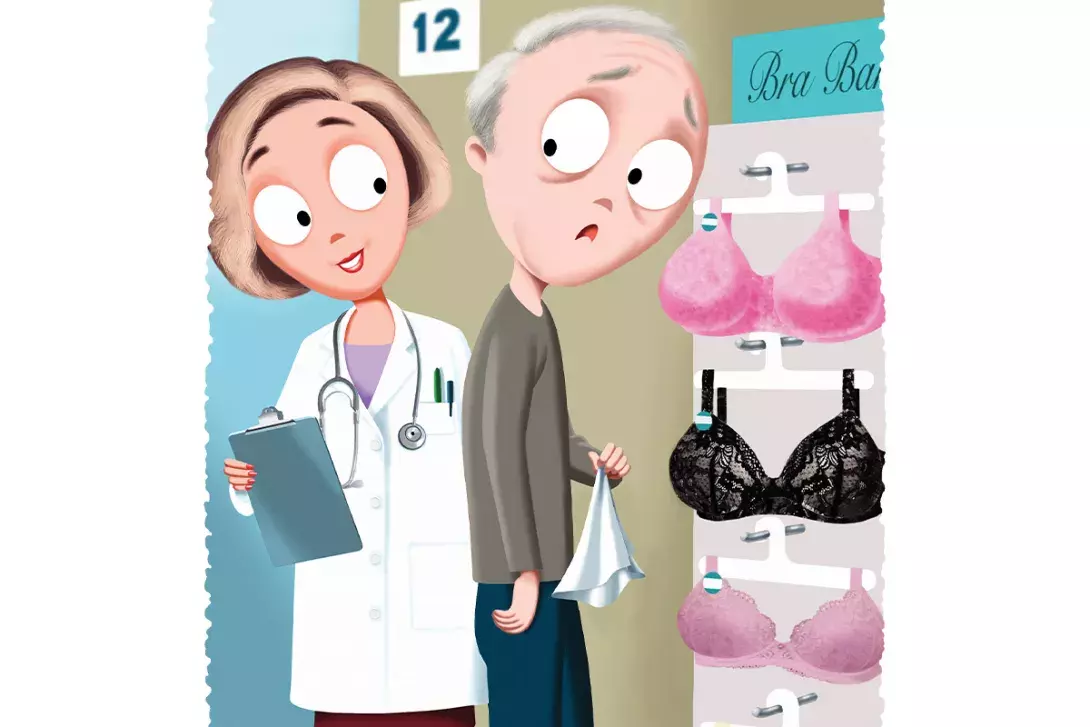

Despite his failing body, he retains a wicked sense of humour. He describes taking a shortcut through the ladies lingerie section of a department store when his body freezes and he finds himself rigid, eye level with a row of lacy bras. He comments how it is impossible to find a salesperson to help when you need them, but the minute he stands, apparently ogling lingerie, a fierce woman is right there. Arms crossed, voice dripping sarcasm, she asks how she can help.

It is a phenomenon in Parkinson’s disease that your limbs can suddenly seize up. If you drop something, you can step over it and initiate forward motion again. Nose pressed into a D cup, Ronald fumbles for a handkerchief, lets it fall and lurches forward, nearly knocking the saleswoman over as he stumbles towards the elevators.

Bed 12 has become Ronald: a person with a loving family and friends, trying his best to live well despite significant losses due to his diagnosis. Reading his story is a defining and powerful lesson, and one I still reflect on three decades later.

However tired I feel, I remind myself that every patient has a unique story, dreams about their future and memories of a past already lived. They have a name, an identity and a right to dignity and respect. I know how I want to be treated should I ever be that anxious, vulnerable patient in Bed 12, and try to provide the care I hope to receive.

On days when I feel overwhelmed and focus on the issue rather than the person in front of me, I reflect on Ronald’s nose pressed against a D cup as he fumbles for the handkerchief that will propel him forward, and find myself smiling. It reminds me to drop in questions about the patient’s interests or their loved ones, so I can learn who they are and what is important to them before rushing to make a diagnosis.

Ronald taught me that empathy is central to finding common ground and rapport with others. And that a little humour never goes astray. MT