Innocence revisited – 6

Our series continues as we move from greeting the patient to taking the history...

Compiled by Dr John Ellard

Give us a cough

Sometimes things are not as uncomplicated as they look. Dr Pelmore, who shared stories with us last issue, is at it again – this time vicariously, in the emergency department.

Seriousness was to our surgical registrar as Nelson’s Column is to Trafalgar Square. The two were inseparable. During a ward round with this registrar, a sister hove into view:

‘There’s a very interesting inguinal hernia in Casualty, doctor’, she said reverently. ‘I thought the students might like to see it.’

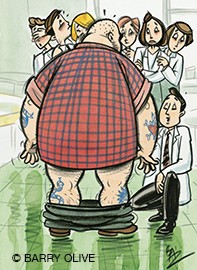

We were frogmarched, straight-faced, down to the bowels of the hospital to the emergency department. A bow wave of people melted away before us. The cubicle curtain was thrust aside, and there before us stood a tattooed, 18-stone truck driver.

‘Drop your trousers, if you would be so kind’, asked the registrar politely.

The throng pressed forward for a glimpse of the poor man’s genitals.

Lo, and behold, there hung the hernia.

Our registrar dropped to his haunches to perform the routine coughing procedure for hernias. Boldly taking the man’s scrotum in his hand, he looked up at the embarrassed truckie, and with a complete slip of the tongue said:

‘Give us a kiss?’

Red marks

I think it was Osler who said we should always listen to patients, for they are telling us the diagnosis. Osler was correct, of course, but for once he did not go quite far enough, since listening to ourselves may lead to great insights. For example, Dr O. Francis soon learned not to ask mothers of six if they had a job, and not to ask welders if they had flashes of light in front of their eyes. But he still had a little way to go, as we shall see:

I have learned that the reply is not always complimentary when the question is: ‘And how did you come to consult me?’ For example:

‘The better-known eye specialists were too busy’, or ‘Because I heard you are the best optician in the suburb’. This is a time when relations between ophthalmology and optometry were less cordial than today. And I was the only eye doctor in the suburb anyway.

One hot day, in my airconditioned surgery, came another explanation that did my ego no good at all:

‘I thought it was about time I had a check up, and it’s cool in here.’

And here’s a lesson I learned only the other day – drum up thoroughly on the patient’s records before you begin the interview.

‘Let’s see’, I thought aloud, as I rifled through my not very clearly written notes, ‘why did I ask you to come back?’

The patient replied, ‘To collect another fee, I suppose.’ But she smiled as she said it and I did find a valid reason when I read my notes carefully.

Another lesson of more recent vintage: don’t be like a second-rate TV interviewer and repeat needlessly what the patient has just told you.

The young man complained that since commencing a course in political science:

‘I get red marks under my eyes with all that reading.’

‘Red marks?’

‘Oh, yes. I’ve read Marx, Keynes and all those sorts of books.’

A question I learned not to ask on the first of June:

‘Have you had any chest trouble this winter?’

‘No, but it only started this morning.’

An innocent ambiguity can be regarded by the patient as an intentional leg-pull. In neither of the following exchanges was I trying to be smart – really!

First patient: ‘I was recently under treatment for scalding of my water, but I’m OK now.’

‘So it was just a passing trouble?’

‘Oh, doctor!’

Second patient: ‘I’m on tablets for fluid. Can’t think of the name. Starts with a “D”. Damn it!’

‘How do you spell that?’

Salvation

Those who interrogate rather than listen confine the history within the limits of their own imagination and will be the poorer for it, never seeing far into another’s mind. For example…

I suspected that there might be a touch of psychosis in the family, and had manoeuvred the conversation around to the lives, habits and eccentricities of its members.

She was talking, half to herself and half to me, turning over the album pages in her memory, ‘And there was grandfather … very loving, but very busy.’

She thought some more.

‘You know, he spent the whole of his life trying to form the Salvation Navy – but it never caught on…’

The great Lokhman

It is important, too, not to be blinkered by one’s culture, or one’s personal tastes. Dr A. Gilani reminds us of a great physician who was not.

Legend has it that the great Arabian physician, Lokhman, was on a voyage when a storm arose, and one passenger on board was so severely affected that he lost consciousness. The time-honoured remedy of smelling salts, perfumed with attar and frankincense, was applied by several well-wishers, but in vain.

In desperation, the crew approached the great Lokhman and sought his help. Lokhman stood over the prostrate form of the unconscious man and asked:

‘Does anyone know this man’s profession?’

Someone in the crowd answered, ‘He is the head cleaner of the vegetable market in the city of Baghdad.’ Whereupon Lokhman asked an attendant to crush some decaying vegetables and place some of the juice in the man’s nostrils.

This was done – and behold! He who was lifeless a moment ago sat up and eagerly looked about him, completely recovered.

It might be prudent to try something a little more orthodox first.

Having taken the history, next month we shall proceed to the physical examination, which has some unexpected difficulties.