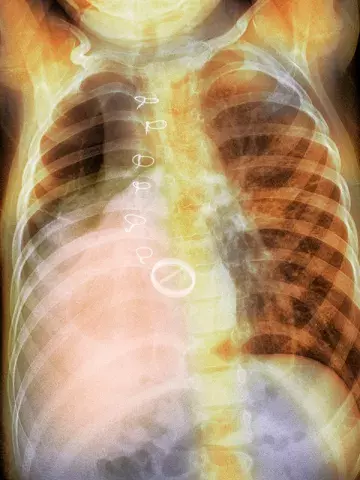

Early childhood lower respiratory tract infections linked to premature respiratory deaths in adults

By Rebecca Jenkins

Early childhood lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) are linked to an almost two times increased risk of dying prematurely from respiratory disease in adulthood, research finds.

‘LRTIs in early childhood are known to influence lung development and lifelong lung health, but their link to premature death from respiratory disease is unclear,’ UK researchers wrote in The Lancet.

Using data from a national birth cohort of more than 5000 participants spanning eight decades, researchers found people who had an LRTI before 2 years of age were 93% more likely to die prematurely from respiratory disease as adults than people who did not have an early childhood LRTI.

The risk would account for one in five (20.4%) premature adult deaths from respiratory disease, they concluded, equating to 179,188 excess deaths across England and Wales between 1972 and 2019.

‘This increased risk remained robust even after adjusting for multiple markers of childhood social disadvantage and adult smoking, and the risk seemed to be specific for respiratory mortality, not for alternative causes of death,’ the researchers wrote.

‘By showing such a substantial link to early childhood LRTI, this study shows there is scope for much earlier preventive interventions and provides a more rounded explanation for existing inequities in survival.’

Of the 5362 participants who were enrolled in the birth cohort in one week in March 1946, 3589 participants aged 26 years were included in survival analysis from 1972 onwards, with a maximum follow-up time of 47.9 years.

Dr Shivanthan Shanthikumar, Paediatric Respiratory Specialist and Clinician-Scientist Fellow at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, said the study added further weight to the long-standing theory that adult lung disease originated in early life.

‘This concept, which is well described from chronic respiratory diseases like asthma, highlights that any insult to respiratory health in the childhood period results in slowed development of lung function, lower peak lung function in early adult life, leaving less reserve to tolerate lung function decline in adult life,’ he told Medicine Today.

‘What is new in this study, and a little surprising, is the magnitude of the effect (i.e. double the risk of death) and that acute LRTI in childhood, as compared to a chronic disease, could have such a profound effect.’

Dr Shanthikumar noted this study could not determine if treatment of LRTIs modified the long-term sequalae, speculating that LRTIs could have this effect regardless of treatment. However, GPs and clinicians could promote childhood lung health by supporting vaccination, which can prevent LRTIs, and educating caregivers around the risks of second-hand childhood smoke exposure from cigarettes and vapes.