Pruritus: understanding the causes, soothing the itch

A careful structured approach to the diagnosis and management of pruritus, with simple intensive topical treatment regimens at least initially, helps patients with pruritus.

- Pruritus is extremely debilitating and prompt management is essential.

- A phone call to a dermatologist regarding a desperate patient should ensure prompt review.

- Dry, sun-damaged skin is itchy and avoiding soap and moisturiser and overheating will help all patients with pruritus.

- A careful history and examination is essential.

- Investigations are only indicated if the diagnosis is not obvious or simple treatments fail.

- Printed patient information and treatment instruction sheets are essential.

Picture credit: © Jacopin/BSIP/SPL

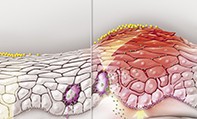

Pruritus (itch) is a common reason for presentation to the primary care physician and is a source of misery to the patient and a challenge to the doctor. It is a feature of many diseases, including allergic, contact, irritant and nummular eczema, idiopathic itch, psoriasis, tinea, systemic disease and urticaria, and it may be a symptom of adverse drug reactions (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3a and b).

An approach to the diagnosis and management of pruritus is discussed in this article. As it is not possible to discuss in detail the treatment of all the conditions that can produce pruritus, the causes highlighted are those responsible for most cases and those that it is important not to miss as they present more challenging management problems, including systemic diseases, neurodermatitis and delusions of parasitosis.

Pathophysiology

Control and elicitation of pruritus involves a complex interaction between skin receptors, the peripheral and central nervous system, and a range of cytokines and neuromodulators produced in the dermis and in keratinocytes.

The sensation of pruritus is transmitted through the primary afferent nerve type C fibres (which, being unmyelinated, are slow-conducting) and possibly also through type A-delta fibres (myelinated and therefore fast-conducting), with the free nerve endings – the nociceptors – located near the dermoepidermal junction or in the epidermis. Activators of the polymodal (chemical, mechanical and thermal) C nociceptors include histamine, neuropeptide substance P, serotonin, bradykinin, proteases (such as mast cell tryptase) and endothelin (which stimulates the release of nitric oxide). A-delta nociceptors are activated by mechanical and thermal stimuli. The sensitivity of these nerve fibres to temperature explains the well recognised phenomenon of a lowered itch threshold when the skin temperature is raised.

Opioids are known to modulate the sensation of pruritus, both peripherally and centrally. Although pruritus is an entirely separate sensory modality from pain, the neural pathways both follow the same overall route from the dorsal route ganglion to the spinothalamic tract and eventually to the thalamus and cerebral cortex.

Under pathological conditions such as tissue damage and nerve injury, the sensation of itch can increase markedly, such that a normally insignificant stimulus can produce itching sensations (alloknesis). Moreover, a normally pruritic stimulus can elicit a greater than normal duration and/or magnitude of itch (hyperknesis).

Diagnosis

At the outset, it is important to know whether the itch is associated with a rash. This is not as easy as it sounds, as sometimes the skin may be covered in excoriations, or even small ulcers, without any other features. The next important feature is whether the itch is localised to a particular area of the body or generalised.

Diagnostic lists based on a simple division of clinical features, determined by the presence or absence of the rash and how much of the body is affected are presented in the Flowchart. The diagnostic clues and the appropriate investigations and management of the conditions are summarised in the Table Page 1 and Page 2.

Scratching the skin can eventually produce secondary changes like lichenification (thickening of the skin), which can be chronic, intensely itchy and treatment resistant (Figure 4). It is essential to reverse the itch–scratch cycle for these patients to get better.

Lichen simplex chronicus is a localised, well-demarcated area of lichenification. It is sometimes termed neurodermatitis. The scratching and/or rubbing appears to heighten the skin sensitivity and alter the itch perception of local nerve endings. Lichenification occurs in many different dermatoses, when there is scratching and rubbing.

Careful examination may reveal dry, slightly scaly xerotic skin without any inflammation. This is a feature of some systemic diseases and is common in the elderly. In Australia, many patients have significant sun damage to their skin, and this is prone to produce dry, itchy excoriated patches on the arms, shoulders and upper back.

In patients with scabies there may be little to find on examination unless the examination is very thorough. Favoured sites for infestation with the scabies mite that should always be checked are the genitals in men and the chest in women.

Some patients, especially older men, develop atypical dermatitic eruptions with no obvious underlying disease but severe itch that is poorly responsive to treatment (Figure 5). Several diagnostic terms for variants have been used, including urticarial dermatitis and ‘itchy red bump disease’.

Patients with urticaria often have no visible wheals at presentation but the history is highly suggestive of the diagnosis. Stroking or rubbing the skin can produce the linear wheals of dermographism, which can be intensely itchy. Some patients may not get a rash unless they rub or scratch, and this is an urticarial variant know as symptomatic dermographism.

The area to which a rash localises can offer important clues for diagnosis, but inflammatory dermatoses such as eczema can ‘systemise’ once the immune system is primed. A good example of this is venous eczema (also known as stasis eczema or gravitational dermatitis), which may be present on the lower legs for months and then spread to the arms and trunk (Figures 6a and b). Grover’s disease is occasionally surprisingly widespread.

Systemic disease

When no other cause is obvious for pruritus, a systemic cause is likely – a diagnosis of exclusion.

Renal pruritus

Renal pruritus is most often seen in patients receiving haemodialysis. The condition is not due to elevated serum urea levels, and the actual pruritogenic substance has yet to be identified. Xerosis greatly exacerbates the condition and raises the ‘itch threshold’.

Cholestatic pruritus

Cholestatic pruritus is more common in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis than in those with extrahepatic cholestasis. It does not appear to relate to bile salt or bilirubin levels. The accumulation of endogenous opioids seems to be involved because opioid antagonists have been shown to partially relieve cholestatic pruritus.

Haematological pruritus

Patients with pruritus and iron deficiency may not be anaemic, suggesting that pruritus may be related to iron and not haemoglobin. Pruritus can be a feature of myelodysplasia. Mastocytosis is generally very itchy due to the high number of mast cells in the skin and sometimes systemically. Polycythaemia rubra vera can also produce very intense pruritus and is associated with aquagenic pruritus.

Endocrine pruritus

Hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism both produce pruritus, the latter especially due to the associated xerosis. Diabetes mellitus is generally included on the list of causes but is unproven.

Pruritus and malignancy

Pruritus has been linked to almost every type of malignancy in numerous reports but in practice is not a common presenting symptom of malignancy. It is, however, a common feature of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The author has seen it present as severe papular urticaria and prurigo following an exaggerated insect bite reaction.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, although rare, is one of the more common T-cell lymphomas and can present with intractable pruritus and what looks like an extensive eczema or psoriasis (Figure 7).

Psychogenic pruritus

Patients may present with severe itch that is so intense that only breaking the skin seems to provide relief. They sometimes admit to scratching when stressed.

The repetitive scratching results in excoriations, erosions and sometimes frank ulcers. Skin that is torn can heal with characteristic white ‘porcelain’ scars, especially on the upper arms and upper back. The itch may be concentrated to single or multiple areas of lichenification that may then go on to form prurigo nodules.

It is essential to reverse the itch–scratch cycle for these patients to get better.

Delusions of parasitosis

Patients with delusions of parasitosis may have pruritus but essentially are convinced that their skin is being infested with insects or other parasites. The descriptions can be bizarre and they may bring containers filled with ‘evidence’ of their infestation containing skin debris. Family members may collude with the diagnosis or describe similar problems.

This is regarded as a psychosis – a psychocutaneous disorder – and is a very serious illness with significant morbidity. Psychiatric referral is essential.

Investigations

Skin biopsy

If a rash is present, a skin biopsy may be helpful in confirming a diagnosis. Punch biopsies (3 mm) should be taken from two or three locations. Inflammatory patches or papules will give the most information; biopsying ulcers and excoriations should be avoided.

Generally, the pathologist will give a description of a ‘reaction pattern’. The diagnosis can only be made from a clinicopathological correlation between the history and what is seen, and what the biopsy reveals.

Blood tests

The author generally orders blood tests when an underlying systemic disease is suspected as the cause of pruritus, and also investigates patients whose inflammatory rash has proved completely refractory to intensive topical, and sometimes systemic, treatment. The diagnostic yield from these tests is low.

The basic screening tests for investigation of pruritus are listed in Box 1. More specific screening such as HIV antibody test, connective disease serology, full thyroid function testing, full iron studies, anaemia screen and hepatitis serology would be predicated by clinical features and the results of initial tests.

Treatment

Simple treatment regimens should be developed. Treatments can be time-consuming, and regimens that involve at the most twice daily activity can help compliance. Patients should be reviewed after one or two weeks of treatment, and moved on to the next step if there is no progress. Referring a distressed patient early if they are no better is a sign of a conscientious physician and will be appreciated by patients (Box 2).

Printed patient information and treatment instruction sheets are essential. Reliable online sources of information for patients with pruritus are provided in Box 3.

Intensive topical treatment

The backbone of all treatment for pruritus is intensive topical treatment. Dry skin is itchy skin. Patients should be encouraged to avoid overheating, which is a problem especially for the elderly and those who are ill. Central heating and slow combustion fires dehumidify the atmosphere, and electric blankets and doonas may increase nocturnal itch. Long hot showers and baths should be avoided.

Soft, synthetic fabrics are kinder to irritable skin than wool or rough natural fibres. Similarly, sand, carpets and upholstery will aggravate atopic dermatitis in small children.

If possible, provide patients with written instructions on skin care and keep regimens reasonably simple. If there is only dry skin and no inflammatory changes then moisturiser is a good starting point, especially in xerosis of the elderly. Always advise the avoidance of alkaline soaps and washes; sorbolene soaps, goat’s milk-based soaps and soaps containing moisturisers (such as Dove) are suitable if patients cannot afford proprietary non-soap cleansers.

Moisturiser in tubs should be used, as it is thicker than moisturiser in pump packs. It should be applied when the skin is wet as water is a good humectant but will worsen skin dehydration if allowed to evaporate. Always smooth on in direction of hair and do not rub because this can cause folliculitis.

If topical corticosteroids are to be used, the author prefers ointment-based more potent corticosteroids such as betamethasone dipropionate, mometasone furoate or methylprednisolone aceponate, provided they are not contraindicated. If patients have an aversion to ointments then a cream may be used. Ointments are more moisturising, better absorbed and significantly more potent. With streamlined authorities, a reasonable amount is easily prescribed on the PBS. The author always instructs patients to apply moisturiser over the corticosteroid. Recommending moisturiser to be used twice a day and topical corticosteroid at night should increase compliance.

Wet dressings can be applied over the applied corticosteroid ointment and moisturiser. For localised areas, cotton bandaging (wet then dry over the top) can be used; for the whole body, use pyjamas wetted with tap water and wrung out and then worn. The bandages can be worn overnight; for the whole body dressings, wrapping in a cotton blanket may be needed for comfort and the wet dressings only applied for an hour once or twice a day. An alternative to wet dressings is a ‘soak treatment’: the patient has a 15-minute oil or oatmeal bath, the topical corticosteroid and moisturiser is applied to the skin without drying and the patient then dresses in light pyjamas and retires for the night.

The rationale for using potent corticosteroids is to achieve good control quickly. Patients should be encouraged to use topical corticosteroids regularly until the skin inflammation has settled and then maintain the skin in that condition with a moisturiser and occasional use of corticosteroid.

The topical calcineurin inhibitors pimecrolimus and tacrolimus (off-label use of tacrolimus, as a compounded ointment) are an alternative to topical corticosteroids. These immunomodulators are similar in potency to hydrocortisone 1% but more expensive. Their advantage is that they do not cause epidermal atrophy, and may therefore be more appropriate for use on the face or longer term in the flexures.

If a patient has had no response after a few weeks of treatment then re-evaluation and consideration of systemic treatment is generally required.

Systemic treatments

Antihistamines are the primary treatment for pruritus when histamine is the principle mediator, as occurs in urticaria. Nonsedating antihistamines are preferable in urticaria, and up to four times the normal recommended dosage may be required.

The sedation provided by traditional antihistamines, and by tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) such as doxepin, may give patients some extra relief at night. Both sedating antihistamines and low-dose TCAs (e.g. 10 mg doxepin or amitriptyline) are often used in patients with nonspecific itch.

Narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy can be extremely helpful in a variety of diseases precipitating pruritus, including urticaria, psoriasis, eczema, idiopathic itch, systemic disease and urticarial dermatitis.

Prednisolone can be used to gain control of very acute dermatitis in patients in whom topical treatment has failed. A moderate dose of about 0.5 mg/kg is adequate to provide relief for almost all patients with pruritus. Start at 25 mg daily and reduce by 5 mg/day every five to seven days; stop at 5 mg/day and review progress. Reducing the dose slowly reduces the risk of rapid flaring below the immunosuppressive level of about 15 mg/day.

Diabetes is not an absolute contraindication for a short course of oral corticosteroids but the patient will need careful monitoring. The prednisolone can be taken in a single morning dose and patients warned of the possibility of disturbed sleep.

When all else fails patients with pruritus may need immunosuppressive medication, at least in the short term, to gain control of the disease precipitating it. The medications that have been shown to work well include azathioprine, ciclosporin, methotrexate and mycophenolate (off-label use for skin conditions). Oral retinoids (such as acitretin) and dapsone can be effective in intractable Grover’s disease and dermatitis herpetiformis, respectively (both off-label uses). Immunosuppressive medications are best prescribed by physicians with relevant experience of prescribing and monitoring these agents.

Treatment of psychogenic pruritus

It is essential to break the itch–scratch cycle for patients with this condition. Topical treatments may help but systemic measures are often required. The GP is the ideal person to provide counselling, support and medication for any underlying depression or anxiety.

Treatment of delusions of parasitosis

Patients with delusions of parasitosis need support without measures that will reinforce the delusion. Referral is essential, and should include a dermatologist and a psychiatrist. Several psychoactive medications have been reported as useful, including risperidone, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and olanzapine.

Conclusion

Pruritus is an extremely debilitating sensation and prompt management is essential. A careful structured approach to its diagnosis and management, with referral early rather than late, will yield rewards. Review is important to gauge treatment efficacy and reconsider the diagnosis. It is also an opportunity for consideration of systemic treatment and eventual referral if there is no progress. MT