Millions of high-risk Australians aren’t getting vaccinated. A policy reset could save lives

Each year, vaccines prevent thousands of deaths and hospitalisations in Australia.

But millions of high-risk older Australians aren’t getting recommended vaccinations against COVID, the flu, pneumococcal disease and shingles.

Some people are more likely to miss out, such as migrant communities and those in rural areas and poorer suburbs.

As our new Grattan report shows, a policy reset to encourage more Australians to get vaccinated could save lives and help ease the pressure on our struggling hospitals.

Adult vaccines reduce the risk of serious illness

Vaccines slash the risk of hospitalisation and serious illness, often by more than half.

COVID has already caused more than 3,000 deaths in Australia this year. On average, the flu kills about 600 people a year, although a bad flu season, like 2017, can mean several thousand deaths. And pneumococcal disease may also kill hundreds of people a year. Shingles is rarely fatal, but can be extremely painful and cause long-term nerve damage.

Even before COVID, vaccine-preventable diseases caused tens of thousands of potentially preventable hospitalisations each year – more than 80,000 in 2018.

Vaccines offered in Australia have been tested for safety and efficacy and have been found to be very safe for people who are recommended to get them.

Too many high-risk people are missing out

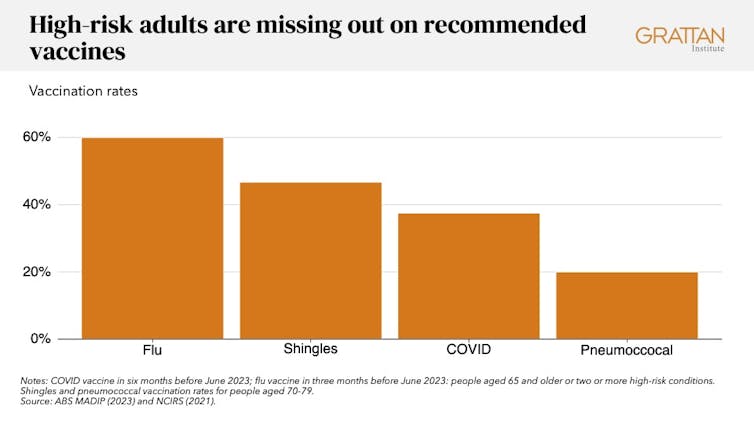

Our report shows that before winter this year, only 60% of high-risk Australians were vaccinated against the flu.

Only 38% had a COVID vaccination in the last six months. Compared to a year earlier, two million more high-risk people went into winter without a recent COVID vaccination.

Vaccination rates have fallen further since. Just over one-quarter (27%) of people over 75 have been vaccinated in the last six months. That leaves more than 1.3 million without a recent COVID vaccination.

Uptake is also low for other vaccines. Among Australians in their 70s, less than half are vaccinated against shingles and only one in five are vaccinated against pneumococcal disease.

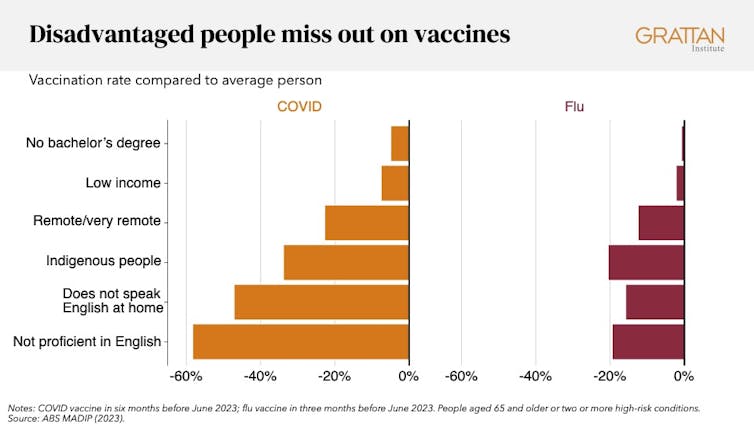

These vaccination rates aren’t just low – they’re also unfair. The likelihood that someone is vaccinated changes depending on where they live, where they were born, what language they speak at home, and how much they earn.

For example, at the start of winter this year, the COVID vaccination rate for high-risk Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults was only 25%. This makes them about one-third less likely to have been vaccinated against COVID in the previous six months, compared to the average high-risk Australian.

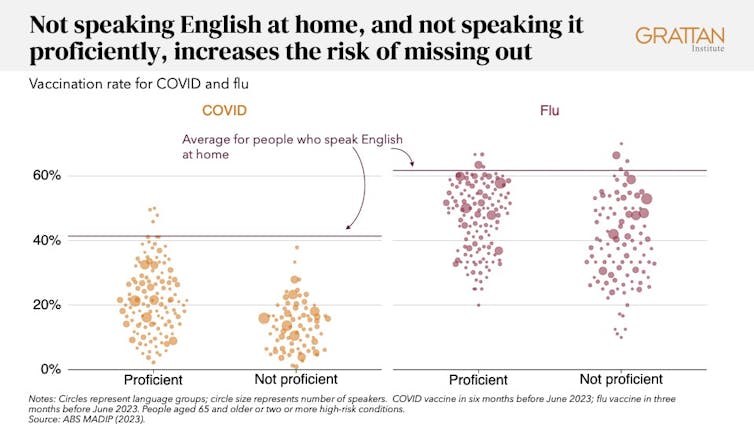

For more than 750,000 high-risk adults who do not speak English at home, the COVID vaccination rate is below 20% – about half the level of the average high-risk adult.

Within this group, 250,000 adults aren’t proficient in English. They were 58% less likely to be vaccinated for COVID in the previous six months, compared to the average high-risk person.

High-risk adults who speak English at home have a flu vaccination rate of 62%. But for people from 29 other language groups, who aren’t proficient in English, the rate is less than 31%. These 39,000 people have half the vaccination rate of people who speak English at home.

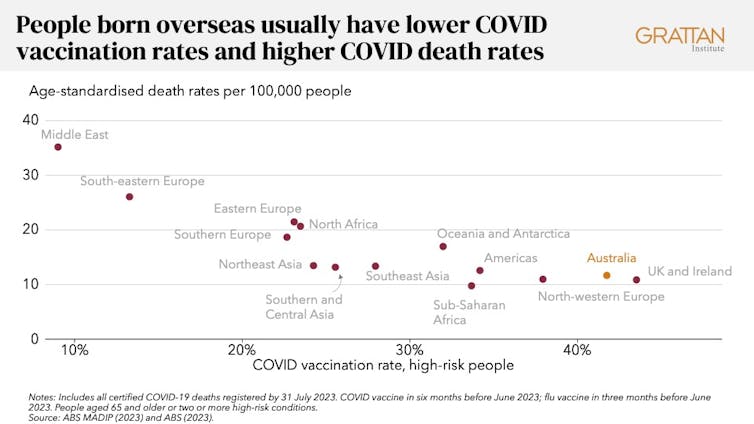

These vaccination gaps contribute to the differences in people’s health. Australians born overseas don’t just have much lower rates of COVID vaccination, they also have much higher rates of death from COVID.

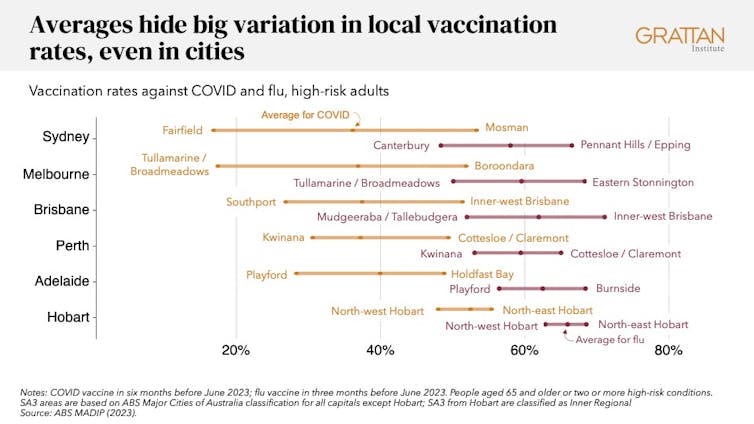

Where people live also affects vaccination rates. High-risk people living in remote and very remote areas are less likely to be vaccinated, and even within capital cities there are big differences between different areas.

We need to set ambitious targets

Australia needs a vaccination reset. A new National Vaccination Agreement between the federal and state governments should include ambitious but achievable targets for adult vaccines.

This can build on the success of targets for childhood and adolescent vaccination, setting targets for overall uptake and for communities that are falling behind.

The federal government should ask the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) to advise on vaccination targets for COVID, flu, pneumococcal and shingles for all high-risk older adults.

Different solutions for different barriers

Barriers to vaccination range from the trivial to the profound. A new national vaccination strategy needs to dismantle high and low barriers alike.

First, to increase overall uptake, vaccination should be easier, and easier to understand.

The federal government should introduce vaccination “surges”, especially in the lead-up to winter, as countries in Europe do.

During surges, high-risk people should be able to get vaccinated even if they have had a recent infection or injection. This will make the rules simpler and make vaccination in aged care easier.

Surges should be reinforced with advertising explaining who should get vaccinated and why. High-risk people should get SMS reminders.

Second, targeted policies are needed for the many people who are happy to use mainstream primary care services, but who don’t get vaccinated – for example, due to language barriers, or living in aged care.

Primary Health Networks should get funding to coordinate initiatives such as vaccination events in aged care and disability care homes, workforce training to support culturally appropriate care, and provision of interpreters.

Third, tailored programs are needed to reach people who are not comfortable or able to access mainstream health care, who have the most complex barriers to vaccination – for example, distrust of the health system or poverty.

These communities are all very different, so one-size-fits-all programs don’t work. The pandemic showed that vaccination programs can succeed when they are designed and delivered with the communities they are trying to reach. Examples are “community champions” who challenge misinformation, or health services organising vaccination events where communities work, gather or worship.

These programs should get ongoing funding, but also be accountable for achieving results.

Adult vaccines are the missing piece in Australia’s whole-of-life vaccination strategy. For the health and safety of the most vulnerable members of our community, we need to close the vaccination gap.

Disclosure statement

Peter Breadon's employer, Grattan Institute, has been supported in its work by government, corporates, and philanthropic gifts. A full list of supporting organisations is published at www.grattan.edu.au.

Ingrid Burfurd's employer, Grattan Institute, has been supported in its work by government, corporates, and philanthropic gifts. A full list of supporting organisations is published at www.grattan.edu.au.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article, published on 27 November 2023.

![]()

Opinions expressed in Something Borrowed are those of the original authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors, the Editorial Board or the Publisher of Medicine Today.