Fracture prevention in postmenopausal women given infrequent zoledronate

By Rebecca Jenkins

An infusion of zoledronate every five or 10 years can prevent vertebral fractures in early postmenopausal women, a large randomised controlled trial suggests.

The bisphosphonate zoledronate was known to prevent fractures in older women when given every 12 to 18 months; however, studies had shown a persistent effect on bone density and bone turnover lasting beyond five years, researchers wrote in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Current fracture-prevention strategies focused on people at highest risk of fracture, they added, an approach that had severe limitations given only 20% of fractures occurred in women with a bone mineral density (BMD) that indicated osteoporosis.

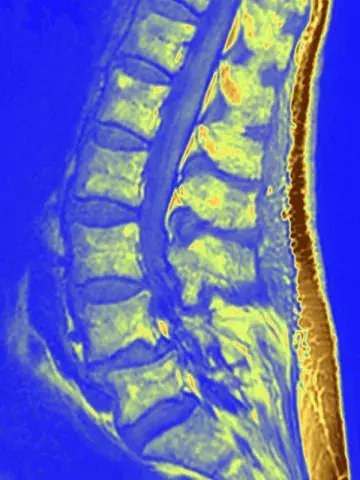

‘Another possibility for the primary prevention of fractures would be to prevent bone loss in early postmenopausal women and maintain BMD near the peak level of a young person,’ the researchers wrote.

The 10-year, prospective randomised placebo-controlled trial enrolled early postmenopausal women (50 to 60 years of age at baseline) with BMD T-scores lower than 0 and higher than –2.5 at the lumbar spine, femoral neck or hip, with scores of –1 or higher typically indicating normal BMD.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three study arms: zoledronate infusion (5 mg) at baseline and at five years (zoledronate–zoledronate group), zoledronate infusion (5 mg) at baseline and placebo at five years (zoledronate–placebo group) or placebo at baseline and again at five years (placebo–placebo group).

Of 1054 women with a mean age of 56 years at baseline, 1003 (95.2%) completed 10 years of follow up, the researchers reported.

A new morphometric vertebral fracture occurred in 22 women (6.3%) in the zoledronate–zoledronate group, in 23 women (6.6%) in the zoledronate–placebo group, and in 39 women (11.1%) in the placebo–placebo group.

The number needed to treat to prevent one woman from having a new morphometric vertebral fracture during the 10-year period was 21 in the zoledronate–zoledronate group and 22 in the zoledronate–placebo group.

Compared with the placebo–placebo group, the risk of any fracture was 0.70 in the zoledronate–zoledronate group and 0.77 in the zoledronate–placebo group.

Markers of bone turnover remained low in the zoledronate– zoledronate group at 10 years, the researchers wrote, with markers increasing after five years in the zoledronate– placebo group but remaining below baseline levels at 10 years.

Professor Peter Wong, Clinical Professor at Westmead Clinical School, The University of Sydney, Sydney, said the study was methodologically robust with almost all patients included in follow up at 10 years.

‘Intriguingly, it raises the possibility of an interesting public health strategy for primary fracture prevention,’ he told Medicine Today.

Professor Wong, who is also Medical Director of Healthy Bones Australia, a national consumer advocacy organisation to reduce broken bones and improve bone health across Australia, said it would be interesting to see further studies on the effect of the protocol in men and older women and also the benefits of the strategy beyond the current 10-year study – i.e. whether it continued to result in fewer fractures.