Innocence revisited – 18

Hospital-based perspectives can have their limitations, as Professor Sir John Scott relates.

The Widow Smith

By the time I had completed medical registrar training, I had gained in self-confidence and was striving to become a well informed professional dedicated to my particular discipline. When the time came to undertake a spell in general practice, I thought I was reasonably prepared.

Before this time, I had enjoyed the privilege of working with a team that was the very model of a modern major general hospital unit. We had acquired the first almoner to work in any hospital in our district. These women were the forerunners of the modern social worker. We took what we thought were careful social histories, shared those with the almoner and did everything to expedite the smooth transition from the acute hospital back to the patient’s home environment. We wrote letters that were considerably longer than those of our specialist colleagues. I wrote such a carefully prepared treatise on Widow Smith.

A lonely tale

We all felt sorry for Widow Smith. She had lost her husband and two sons in the Second World War. She had weathered her two pregnancies relatively well, despite having rheumatic endocarditis. When I met her, 14 years after the third of her triple tragedies, she had combined mitral and aortic disease that was not amenable to the cardiac surgery that was available at the time. The almoner was deeply concerned about her problem – a perceived combination of lonely widowhood and chronic heart disease – and shared my misgivings in acceding to the demands of Widow Smith that she be discharged home without a period of convalescence. All this was set out carefully in my letter to her general practitioner. Nevertheless, her demands were met.

Flushed with a recently acquired MRACP, I proceeded into a long term locum in general practice. The principal, whom I was relieving, took me around the practice, which was acknowledged to be one of the best in the district. There was a twinkle in his eye when he ended the tour saying, ‘and on Monday you must visit Widow Smith’. In those days, about half of one’s time was spent doing ‘domiciliary’ visits.

My previous confidence in the hospital-based perspective was somewhat shaken. What more could there be to Widow Smith’s circumstances? I knew that the principal in question had superb knowledge of his patients and exercised great skill, characterised by universally acknowledged sound judgment.

A different perspective

Monday morning came, and I proceeded in my Morris Minor. Widow Smith’s small but extremely well presented home. To my surprise, a healthy man of about her age greeted me, somewhat sleepily, in his pyjamas and dressing gown. He turned out to be the night supervisor at a major industrial plant, but there was more to come.

The man was perhaps a little embarrassed, as would be the case in those days, when he explained that he did the ‘day-watch’ as Widow Smith’s companion and comforter, in all senses of the word. Another man, who worked at a day job, completed the ménage à trois as the night-time partner of Widow Smith. Both men were grateful for what the hospital had achieved – their bedtime companion was much less breathless than before her admission to hospital.

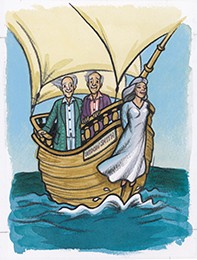

At about that time a film entitled The Captain’s Table was released. This was the story of a skipper whose boat plied the western Mediterranean and the Strait of Gibraltar. He had a mistress at the northwestern port and another at the southwestern port. While things became a bit tangled for him in the course of the film, the seas for Widow Smith were not rough during my time in that practice.

When I left the practice I registered my gratitude to the returning principal and acknowledged that hospital-based perspectives had their limitations. He murmured ‘Plus ça change, c’est plus de la même chose’ (the more things change, the more things stay the same). MT