What’s the diagnosis?

A unilateral facial rash with ocular involvement

Case presentation

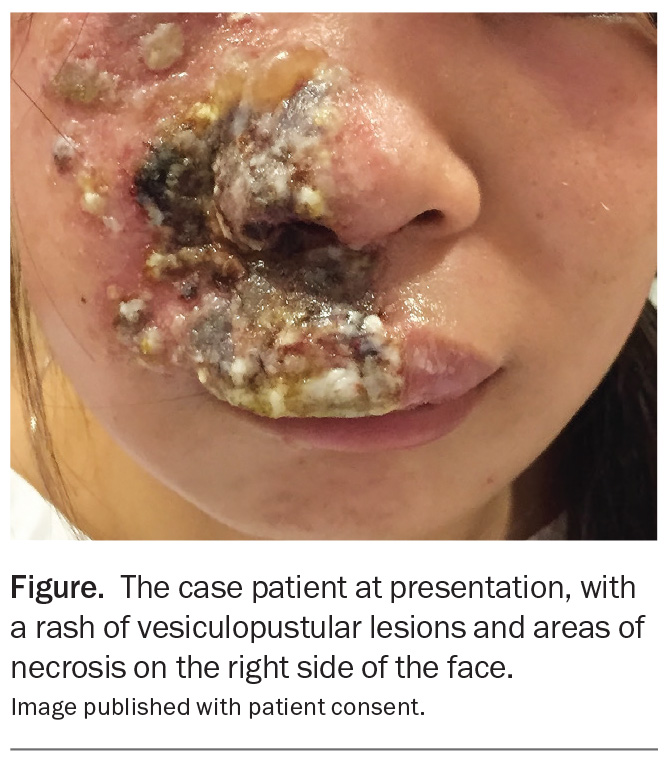

A 24-year-old woman presents with a three-day history of a painful eruption on the right side of her nose and upper lip that extends onto her cheek (Figure). The rash initially appeared as small red papules but has progressed to clustered vesicles, bullae with crusting and ulceration. She reports severe burning pain, increasing facial swelling and heightened sensitivity to light.

The patient describes a low-grade fever of 37.5oC with malaise and a ‘tingling’ sensation on the affected side of her face three days before the rash appeared. She has a history of rheumatoid arthritis, which is treated with methotrexate.

On examination, an extensive unilateral rash of vesiculopustular lesions and areas of necrosis is observed that particularly affects the upper lip and perinasal and periorbital regions. There is mild conjunctival injection but no significant ocular changes.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Autoimmune blistering diseases

Autoimmune blistering diseases are a group of rare disorders in which the immune system attacks proteins that are essential for maintaining skin and mucosal integrity, resulting in blister formation. There are two main categories: intraepidermal blistering (such as pemphigus foliaceus and vulgaris) and subepidermal blistering (such as bullous pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita).1 The incidence of autoimmune blistering diseases varies worldwide, with bullous pemphigoid being the most common, particularly among individuals over 60 years of age.2 Pemphigus vulgaris is more frequently seen in younger individuals, with a higher prevalence in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern populations.2

Clinically, autoimmune blistering diseases present with pruritus, blisters and erosions affecting the skin and mucous membranes. They have predilections for different body sites, with blisters forming on the skin or mucous membranes lining the mouth, nose, throat, eyes or genitals, depending on the disorder. Patients may experience pain and secondary infections, leading to impaired quality of life.

The aetiology of autoimmune blistering diseases involves autoantibodies targeting structural proteins like desmogleins (in pemphigus disorders) or hemidesmosomal proteins (e.g. in bullous pemphigoid). The onset of disease can also be triggered by genetic predisposition, environmental factors and certain medications – these include dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, loop diuretics and penicillin and its derivatives, as well as certain antibiotics.3,4 Investigations may include histopathology, direct immunofluorescence testing and serum antibody assays.

An autoimmune blistering disease was a less likely diagnosis for the case patient, whose rash was unilateral with a dermatomal distribution and had evolved rapidly. These diseases typically present with more widespread blisters or erosions.

Folliculitis

Folliculitis, an inflammatory condition of the hair follicle, is prevalent worldwide (particularly in areas with a warm, humid climate) and can affect any individual, regardless of age or gender. It is more common in patients with a history of diabetes and obesity and is often linked to prolonged use of antibiotics and immunosuppression, as well as shaving and wearing of occlusive clothing.5

Folliculitis presents clinically as small, erythematous pustules or papules centred around hair follicles, often accompanied by itching or tenderness. It can affect any hairbearing area of skin, most commonly on the chest, back, buttocks, arms and legs. Folliculitis can be classified as superficial or deep, depending on the extent of follicular involvement, and severe cases may progress to abscess formation or scarring. Common forms include bacterial and fungal folliculitis and pseudofolliculitis barbae.6 Bacterial folliculitis is most often caused by Staphylococcus aureus but Gram-negative organisms can be implicated. Fungal folliculitis is usually caused by Malassezia species. Pseudofolliculitis is caused by ingrowing hairs that re-enter or remain trapped within the skin, leading to an inflammatory response that is characterised by papules and pustules; it commonly occurs in areas that are subjected to frequent hair removal, such as the face, neck and groin.

The diagnosis of folliculitis is primarily clinical. However, bacterial cultures or fungal scrapings may be required for confirmation in refractory cases.6,7

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. The severity of her vesiculopustular lesions and their distribution (unilateral and following a dermatomal pattern rather than folliculocentric) were more consistent with a different disease.

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis is caused by a delayed (type IV) hypersensitivity reaction. Sensitisation occurs when an allergen activates T lymphocytes, which trigger inflammation on subsequent exposures.8 At least 20% of the general population have a contact allergy to at least one common environmental allergen, with the prevalence being significantly higher in women.9 Common allergens include fragrances, nickel and rubber accelerants.10

Allergic contact dermatitis results in eczematous inflammation that is often confined to areas of exposure, particularly the hands, feet and lips, but the eruption may not remain limited to the initial site of contact. Patients may present with erythema, oedema, pruritic vesicles and blisters. Chronic or repeated exposure can lead to lichenification, scaling and fissuring.11

Allergic contact dermatitis is generally a clinical diagnosis that is supported by a history of exposure to a putative allergen. If suspecting this diagnosis, it is important to ask carefully about potential exposure to new substances, including the use of personal care and cosmetic products and occupational and environmental exposure, as well as any prior allergic reactions. Patch testing, which identifies specific allergens responsible for the reaction, may be used to confirm the cause.11

The case patient did not have a history of exposure to new allergenic products before the rash onset and the unilateral distribution was not consistent with a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis.

Erysipelas

Erysipelas is a bacterial skin infection characterised by a bright patch of erythema and oedema with a well-demarcated border. It primarily affects the upper dermis and superficial lymphatics and is most commonly caused by Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus).12

Erysipelas presents with sudden onset of fever, chills and malaise, followed by the appearance of a bright red area on the skin that is firm and swollen with a sharp, raised border. The lower extremities are most commonly affected; however, facial involvement can occur, with patients often displaying a characteristic ‘butterfly’ distribution across the cheeks and nose. The lesion expands rapidly via lymphatic vessels and may be associated with bullae or petechiae.

The risk of erysipelas is increased by skin barrier disruptions. Entry points for infection include sites of skin trauma (e.g. wounds, insect bites), ulcers or fungal infections such as tinea pedis.13 Erysipelas is more common in infants and elderly patients, and the incidence is higher in those with chronic venous insufficiency, lymphoedema and immunocompromised states such as diabetes or alcohol dependence.14

For the case patient, the vesicular eruption on an erythematous base, progressing from papules through vesicles to crusting lesions in a unilateral distribution, was not typical of this diagnosis. Erysipelas presents with a uniformly bright erythematous area and associated swelling, typically in a butterfly pattern crossing the midline when affecting the face.

Herpes zoster

This is the correct diagnosis. Herpes zoster (shingles) is a reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) – the virus that is responsible for chickenpox. Following primary infection, VZV remains latent in the dorsal root ganglia and can reactivate years later, typically when cellular immunity is waning. This reactivation leads to a painful vesicular dermatomal rash accompanied by neuropathic pain, which can persist after rash resolution (postherpetic neuralgia).15 The incidence of herpes zoster increases with age, particularly beyond 50 years, and is more common in those who are immunosuppressed due to conditions such as HIV infection or malignancy or receiving immunosuppressive therapy.16

The global burden of herpes zoster is significant: the estimated lifetime risk is 25 to 30%, and this figure increases to over 50% in individuals who reach 85 years of age.17 The introduction of VZV vaccines has reduced the incidence in vaccinated populations; however, breakthrough cases still occur.18

Herpes zoster has a prodromal phase characterised by localised pain, itching or burning in the affected dermatome, which may precede the rash by several days. The rash itself consists of grouped vesicles on an erythematous base that follow a unilateral dermatomal distribution, most commonly affecting thoracic, cervical and ophthalmic regions.19 In individuals who are immunocompromised, the rash may become disseminated, extending beyond the primary dermatome. Systemic symptoms such as fever, headache and malaise can also occur.20

The aetiology of herpes zoster is closely tied to immune function. Although VZV-specific immunity remains stable for years following varicella infection, advancing age and the development of chronic diseases (e.g. diabetes, chronic kidney disease) and immunosuppressive conditions lead to a decline in VZV-specific T-cell immunity, which allows for viral reactivation.21 Psychological stress, trauma and exposure to immunosuppressive medications, such as corticosteroids or chemotherapy, are recognised triggers.22 Herpes zoster is infectious to people who have not previously had chickenpox.

Diagnosis and investigations

Herpes zoster is primarily a clinical diagnosis made on the basis of the characteristic unilateral, dermatomal vesicular rash. However, it can be challenging to diagnose, particularly in the prodromal stage when patients may present with nonspecific symptoms that can be mistaken for musculoskeletal pain, neuropathy or other dermatological conditions. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion, especially in high-risk populations, such as elderly and immunocompromised individuals.

Laboratory confirmation may be required for atypical cases or immunocompromised patients. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is the gold standard for detecting VZV DNA in vesicular fluid or crusts or, for patients with herpes zoster meningitis or encephalitis, in the cerebrospinal fluid.23 Direct fluorescent antibody testing of skin lesions is another testing option but has lower sensitivity than PCR.24

Serological tests are not useful in the diagnosis of acute reactivation of VZV. In the primary infection (chickenpox), IgM is often detectable early; however, the response is inconsistent in herpes zoster and often absent or weak.25 The prior exposure results in persistent VZV IgG positivity.23

Management

Early commencement of antiviral therapy, started within 72 hours of rash onset, is crucial to reducing the severity and duration of symptoms in herpes zoster and can significantly reduce complications such as postherpetic neuralgia and prolonged pain syndromes.26-28 Three antiviral agents – aciclovir, famciclovir and valaciclovir – are available for the treatment of herpes zoster. The current Australian guidelines recommend valaciclovir (1 g three times daily for seven days) or famciclovir (500 mg three times daily for seven days [10 days for immunocompromised patients]) as first-line treatments and aciclovir (800 mg five times daily for seven days) as second-line treatment, noting evidence that famciclovir and valaciclovir are more effective in reducing acute pain in patients with herpes zoster.29 Famciclovir and valaciclovir have superior bioavailability and more convenient dosing than aciclovir.26 Intravenous aciclovir (10 mg/kg three times daily) is reserved for severe cases, such as disseminated disease or central nervous system involvement.26,29

Pain management is an integral component of management.30 A stepwise approach is recommended, starting with simple analgesics like paracetamol or NSAIDs.26 For more severe pain, opioids may be considered.28 Adjunctive therapies such as gabapentin or pregabalin can be used, particularly if there is a risk of persisting neuropathic pain after resolution of the rash (postherpetic neuralgia).25,28

Vaccination is available for the prevention of herpes zoster. The recombinant zoster vaccine (RZV, Shingrix) is preferred over the live attenuated vaccine because it has higher efficacy, especially in older adults.31 RZV is recommended for individuals aged 50 years and over, administered according to a two-dose schedule.31 As of November 2023, RZV has been funded under the National Immunisation Program for certain groups: it is available for all adults aged 65 years and over, Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander people aged 50 years and over, and selected groups aged 18 years and over with moderate or severe immunocompromise.31

Outcome

The case patient was diagnosed with herpes zoster on the basis of her clinical features. The rash of vesiculopustular lesions followed the distribution of the right maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve, and sensory examination revealed hyperaesthesia in the affected dermatome. A PCR test, performed on a specimen from vesicular fluid, returned a positive result for VZV DNA. It is likely that methotrexate, which has immunosuppressive activity, was a trigger for a severe episode of the disease.

The patient was treated with valaciclovir and simple analgesics. She was referred for ophthalmic review, where no epithelial defects were identified. Ophthalmologists play a crucial role in diagnosing and managing herpes zoster ophthalmicus to prevent long-term complications such as corneal scarring, chronic pain and vision loss.

The patient’s skin eruption resolved after several weeks. Follow-up at three months showed gradual pain improvement with no lesion recurrence, but she was left with residual scarring. If she continues on long-term immunosuppressive therapy, she would satisfy National Immunisation Program criteria for funded RZV vaccination. Immunocompetent people can wait at least 12 months after an episode of herpes zoster before they receive a zoster vaccine as a lower recurrence rate is observed in the first year; immunocompromised people are at higher risk of recurrence and should receive VZV from three months after the acute illness.31 MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Daniel BS, Murrell DF. Review of autoimmune blistering diseases: the pemphigoid diseases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: 1685-1694.

2. Taş Aygar G, Gönül M. Skin blister formation and subepidermal bullous disorders. In: Maurício AC, Alvites RD, Gönül M, eds. Wound healing – recent advances and future opportunities. IntechOpen; 2023.

3. Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Modern diagnosis of autoimmune blistering skin diseases. Autoimmun Rev 2010; 10: 84-89.

4. Verheyden MJ, Bilgic A, Murrell DF. A systematic review of drug-induced pemphigoid. Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100: adv00224.

5. Winters RD, Mitchell M. Folliculitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

6. Luelmo-Aguilar J, Santandreu MS. Folliculitis: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2004; 5: 301-310.

7. Natsis NE, Cohen PR. Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus skin and soft tissue infections. Am J Clin Dermatol 2018; 19: 671-677.

8. Gober MD, Gaspari AA. Allergic contact dermatitis. Curr Dir Autoimmun 2008; 10: 1-26.

9. Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP, Johansen JD. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis 2019; 80: 77-85.

10. Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP, Johansen JD. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis 2019; 80: 77-85.

11. Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, Pootongkam S, Nedorost S, Brod B. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74: 1029-1040.

12. Stevens DL, Bryant AE. Impetigo, erysipelas and cellulitis. In: Ferretti JJ, Stevens DL, Fischetti VA, eds. Streptococcus pyogenes: basic biology to clinical manifestations. Oklahoma City (OK): University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center; 2016.

13. Bonnetblanc J-M, Bédane C. Erysipelas: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003; 4: 157-163.

14. Bartholomeeusen S, Vandenbroucke J, Truyers C, Buntinx F. Epidemiology and comorbidity of erysipelas in primary care. Dermatology 2007; 215: 118-122.

15. Patil A, Goldust M, Wollina U. Herpes zoster: a review of clinical manifestations and management. Viruses 2022; 14: 192.

16. Harpaz R, Leung JW. The epidemiology of herpes zoster in the United States during the era of Varicella and herpes zoster vaccines: changing patterns among children. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69: 345-347.

17. Yawn BP, Saddier P, Wollan PC, Sauver JLS, Kurland MJ, Sy LS. A population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction. Mayo Clin Proc 2007; 82: 1341-1349.

18. Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al; Shingles Prevention Study Group. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 2271-2284.

19. Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med 1965; 58: 9-20.

20. Nagel MA, Gilden D. Neurological complications of varicella zoster virus reactivation. Curr Opin Neurol 2014; 27: 356-360.

21. Weinberg JM. Herpes zoster: Epidemiology, natural history, and common complications. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57(6 Suppl): S130-S135.

22. Cebrián-Cuenca AM, Díez-Domingo J, San-Martín-Rodríguez M, Puig-Barberá J, Navarro-Pérez J; Herpes Zoster Research Group of the Valencian Community. Epidemiology and cost of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia among patients treated in primary care centres in the Valencian community of Spain. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11: 302.

23. Sauerbrei A, Eichhorn U, Schacke M, Wutzler P. Laboratory diagnosis of herpes zoster. J Clin Virol 1999; 14: 31-36.

24. Gershon AA, Breuer J, Cohen JI, et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015; 1: 15016.

25. Min SW, Kim YS, Nahm FS, et al. The positive duration of varicella zoster immunoglobulin M antibody test in herpes zoster. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95: e4616.

26. Wehrhahn M, Dwyer D. Herpes zoster: epidemiology, clinical features, treatment and prevention. Aust Prescr 2012; 35: 143-147.

27. Gnann JW Jr. Antiviral therapy of varicella-zoster virus infections. In: Human herpesviruses: biology, therapy, and immunoprophylaxis [chapter 65]. Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, et al, eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

28. Adriaansen EJM, Jacobs JG, Vernooij LM, et al. 8. Herpes zoster and post herpetic neuralgia. Pain Pract 2025; 25: e13423.

29. Shingles. In: Therapeutic guidelines: antibiotic. Melbourne; TG; 2019 [amended 2022]. Available online at: https://tg.org.au (accessed March 2025).

30. Acute pain associated with shingles (herpes zoster). In: Therapeutic guidelines: pain and analgesia. Melbourne; TG; 2020. Available online at: https://tg.org.au (accessed March 2025).

31. Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI). Zoster (herpes zoster). In: Australian immunisation handbook. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Available online at: https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/contents/vaccine-preventable-diseases/zoster-herpes-zoster (accessed March 2025).