Innocence revisited – 15

This month, Dr Warwick Carter describes a diagnosis – and retreat – made in haste.

Down and out

An unpleasant experience

‘You’ve got to visit Mrs J at the end of surgery, she’s got a pain in her gut.’ The receptionist’s comment to me – the junior locum in the inner city general practice – was the start of quite a saga.

In the early evening I arrived at Mrs J’s terrace house, which was by far the most dilapidated in a street that gentrification had barely touched. The door was opened by her husband, dressed in shorts, singlet and a three-day stubble of beard. The house, and Mr J, smelled of decaying food, stale beer and a lack of personal hygiene.

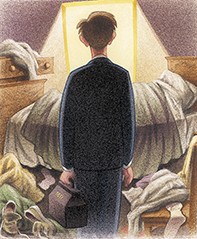

I was told ‘the missus’ was upstairs in bed. Scrambling over piles of dirty clothing, around young urchins, and past the open door of a teenage disaster zone blaring maximum volume pop music, I found the patient. She was trying to doze in her bed – quite unsuccessfully – due mainly (I thought) to the loud music, as well as to the pain in her gut. The bedroom floor and bed were covered in discarded clothing, and the room was pungent with the odour of faeces and sweat.

The history was brief – in the past 12 hours she had slowly developed a worsening bellyache; this had been followed by diarrhoea. She had no appetite, was mildly febrile but had no other complaints.

Regular bathing was not one of Mrs J’s strong points. She was obese, and examination of her abdomen was not performed with great enthusiasm. She was tender everywhere, but (to the best of my recollection) there was no guarding or rebound. I made a hasty diagnosis of gastroenteritis and advised her on the correct diet and to use paracetamol, before beating a rapid retreat through the chaos and smells to the fresh air of the street.

I knew now why the practice partners had sent me on such an unpleasant visit.

A sudden demise

The phone call at 6 a.m. the next morning was a shock. ‘Mum’s dead and Dad says you’ve got to come straight away.’ Mrs J’s teenage son’s bland statement had me up and running in no time.

The circumstances in the house had changed in only two ways: the music was off and Mrs J was cold in her bed. I was dumbfounded and had absolutely no idea what had happened. Thoughts of ruptured appendix or bowel crossed my mind, but I really couldn’t explain her sudden demise. The discussion with the husband was one of the most difficult of my life. The discussion of the case with the partners later in the morning was not much easier.

Naturally I felt extraordinarily guilty, and begged time off to attend the postmortem. Going straight to the point, the pathologist opened Mrs J’s corpse from neck to pubes, and the peritoneal cavity was explored. The back wall of the peritoneum was black, and when incised, a large collection of retroperitoneal blood was found.

The pathologist knew immediately what the diagnosis would be, but it took me a couple of minutes to comprehend what I was being shown – a swollen aorta with a fragile torn wall. Mrs J had died from a ruptured aortic aneurysm at 42 years of age.

The cause of the aneurysm at such a young age was a mystery at first, but later tests showed it to be secondary to syphilis. The leaking aneurysm had caused peritoneal irritation, which in turn caused gut inflammation and diarrhoea. Mrs J’s obesity may have lessened the tenderness and guarding that would have been elicited in a thinner patient.

A lesson learned

The main lesson learned was not the rare presentation of an unusual diagnosis but that, regardless of the unpleasant circumstances, a doctor should always question carefully and thoroughly examine his or her patient. MT