Innocence revisited – 26

Professor Gillian Shenfield recalls four incidents that reveal the hazards faced by a young woman in a ‘man’s world’.

When I was a student, 90% of my colleagues were male and most patients thought of ‘women doctors’ as oxymorons. I still cringe when I remember some of my experiences.

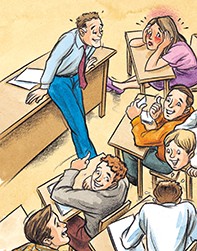

The eager medical student

As a student locum I looked after a man with pelvic vein thromboses, grossly enlarged blue legs and a bizarre rash on the lower half of his body. His consultant was the surgeon who later conducted our final revision course. On the first day of the course the consultant put up a slide and asked me to make a diagnosis. I looked at the man’s legs and said, ‘I recognise this patient’.

As hilarity broke out I realised that the man was completely naked. For the next two months it became a running joke. Every topic or question remotely connected to male urogenital function was addressed to me with the comment, ‘You’ll know this since you’re our expert in these areas’. After my initial embarrassment I found that it was easier to go with the flow and join in the general amusement. It even earned me a few beers.

Today I would probably be able to claim immense damages for sexual harassment. However, this was a very mild experience compared, for example, with the behaviour of some surgeons in operating theatres. Unfortunately, it did not prepare me for the next patient.

The embarrassed young man

It was my first day as a doctor, and things had not gone well. I had taken blood from six young women, all of whom were dying of metastatic breast cancer, and reviewed 20 postoperative patients while the ward sister catechised me with exaggerated deference. Our team was on call and I admitted numerous women and children with acute abdominal pain. By 10 p.m. my male colleague was assisting in theatre and I was carrying both our pagers.

His pager went off and summoned me to the emergency department. I found a young man who looked exceptionally embarrassed when he saw me. In a broad Irish accent he said, ‘It was like this, doctor: I had sex with my girlfriend this afternoon and it hasn’t gone down since’.

I had two sensible options: wait until my registrar emerged from theatre or take a proper history and examine the patient. In my stressed and embarrassed state I did neither. I took a deep breath, pulled back the sheet, shut my eyes, replaced the sheet and ran up to theatre to ask how to treat priapism.

Half an hour later the team arrived to discover that ‘it’ was not the penis but the foreskin. I was mortified, and by the time I crawled miserably into bed at 2 a.m. I had made a serious resolution to give up medicine. I think it was only fear of ridicule that stopped me resigning the next morning.

The call had been intended to provide ‘light relief’ for my male colleague, but I learnt the lesson that to make a diagnosis one must examine the patient – until the next incident.

The noisy psychiatric patient

By this time I had passed my physician’s membership and was a locum registrar in a busy London district hospital.

On my first day (perhaps I should stay in bed on first days) I had to get to know about 30 patients with conditions as varied as myocardial infarction, stroke, endstage airways disease and tuberculous peritonitis. As I worked my way down the ward I was aware that a young West Indian man was making an incredible amount of noise. I asked one of the nurses what was going on. ‘Don’t worry’, she said, ‘he was transferred here with pneumonia from a psychiatric hospital. Now he shouts out and masturbates whenever one of us walks past. We’re trying to get him transferred back to a psychiatric bed’.

This seemed a little bizarre but I had more pressing problems, and it was midafternoon before I reached him. I rapidly discovered that the poor man had been suffering from priapism all day.

I was appalled at my negligence. I administered heparin and rang the surgeons, who operated within the hour, but I suspect that he never recovered his sexual function. Timeliness is an essential part of a physical examination.

The angry consultant

A year earlier, I had been a resident at the Brompton Hospital’s country annexe in Surrey, England. The workload was light, but two residents shared all on call duties.

One Friday afternoon the ward sister asked me to see a Pakistani man who was being treated for tuberculosis. He was extremely anxious because he had not had his usual erection for the previous three mornings and was convinced that he would be permanently impotent. I did my best to reassure him about the side effects of essential drugs and went away for my weekend off. I did not tell the consultant or my fellow resident. On Monday morning I found my colleague pale and shaken. At 6 a.m. the patient had performed a very neat tracheotomy on himself. By some miracle he had avoided cutting any significant blood vessels. He had been given a tracheotomy tube and dispatched to the nearest surgeon. My first shameful thought was relief that I had not been on call.

The consultant summoned me to his office and gave me the most abusive criticism that I received in my entire career. He screamed that I should have told him about the problem and taken impotence more seriously.

At the time I felt guilt, shame and an early feminist anger at male priorities. With the advantage of hindsight I accept that I did not take the patient’s concerns as seriously as I should have done, but I doubt that a man-to-man chat with the very unempathic consultant would have made any difference. I suspect that the consultant’s anger was the only outlet he could find for his own guilt at having failed to elicit the history himself.

Conclusion

I do not defend my mistakes, but I believe they arose from a combination of the attitudes of the time, the stresses intrinsic to my working conditions and, of course, my innocence. MT