Innocence revisited – 25

This month Professor Sir John Scott reflects on his handling of a surprise accusation.

From early adolescence onwards I always admired and envied contemporaries (usually boys) who could remember every joke they had ever been told, and who were experts in rapid-fire repartee. Judicious exhibition of such skills can be useful from time to time in clinical practice, although overuse should be discouraged. In the wider world and the jungle of medical politics, the advantages accruing to the possessor of these talents are obvious.

My genetic background and formative environmental expe.riences failed to provide me with these social skills. Fortunately, my professional career took place in quieter, less competitive, and certainly less defensive-medicine-influenced times. How would or should the average young doctor react today to the situation in which I found myself 42 years ago?

The alcoholic

The patient in question was massive in size, overflowing with confidence and possessed of an overpowering ego. He had started off as a clerk but later became the managing director of a very major company. He was acknowledged to be a chronic alcoholic by his family, and he freely admitted to a liking for all that was good in life generally.

By the time I knew him and had to handle his medical problems, he was indulging in heavy drinking bouts which were superimposed on a moderately steady daily intake of spirits. These episodes were likely to end with vomiting, anorexia and a temporary withdrawal from alcohol. The inevitable DTs ensued. My job was to pin him down and inject the dreadful drug paraldehyde into his buttocks so that he became manageable within his family home, preferably without developing an abscess, which was the usual side effect of such brutal procedures. Valium and similar agents had not then been introduced into this dramatic context.

All at sea

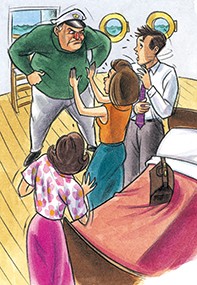

One night I was called to the home. His daughter had telephoned – she had worked with me as a staff nurse and was the person holding the family together. His much-battered wife was cowering in the background. As far as the patient was concerned, everything in the room was part of his yacht. He was particularly incensed because I was in bed in a bunk with his wife. The seas were indeed rough. The daughter and I eventually subdued him enough to administer the magic potion.

A few days later he came into the surgery, seemingly under control, although the odour of drink was upon his lips, so to speak. I was surprised to see him: he or the family normally called me to attend him at his home. I was apprehensive; however, I relaxed when he commenced with a seemingly contrite approach. Was he at last becoming a candidate for Alcoholics Anonymous? The optimistic thought flashed through my mind.

‘I got it wrong the other night, Doc.’

‘Yes’, I replied.

‘I was a bit muddled. You weren’t in bed with my wife, you were…with my daughter in the bunk.’

I botched the rest of the ‘discussion’. Taken by surprise, I indicated tersely that I was offended by his accusation, and rapidly ended the ‘consultation’. He left, angry with me.

It didn’t matter then: times were different. But these days my inept response to his sudden accusation might well have had serious consequences. Hopefully a young doctor today would make a cheerful, witty response and proceed to the next business. MT