Innocence revisited – 34

Children’s interpretations of events often catch us by surprise, as Professor Henry relates.

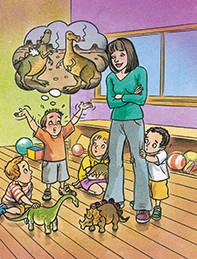

Smoking dinosaurs

The harmful effects of cigarette smoke are important to most doctors but especially to a respiratory paediatrician. Hence I have always been attracted by the Gary Larson cartoon that has the caption, ‘The real reason dinosaurs became extinct’.1 It shows dinosaurs wandering the earth with cigarettes in their mouths. A copy of this cartoon was prominently displayed in my office for several years and patients and their parents would notice this when they came to see me. In fact it became a real conversation piece with parents.

Sometime later a mother rang me to tell me of an event that had occurred at her son’s school. Let us call him Peter. Peter was in kindergarten and his teacher greeted his mother one afternoon in some distress. The teacher said that Peter had become very upset during class and she was not sure why this had occurred. However, Peter’s mother had pieced together the jigsaw and was now ringing to tell me the events.

That particular day the kindergarten class had discussed dinosaurs. Peter had been very excited about this and indicated that he knew the real reason that dinosaurs had become extinct. Naturally his teacher asked him to tell the class what the explanation was. When Peter said that it was because dinosaurs smoked, his teacher gently explained to him that this was not the case. Peter stoutly held to his opinion that it was the case and cited as his reference the fact that his doctor (naturally a respected person beyond reproach) and his mother (with far stronger credentials) had told him. Unfortunately, his teacher was unaware of the Larson cartoon and so she was confused about dinosaurs and smoking. The final result was a terrible day for Peter.

As a Professor of Paediatrics I try to impress upon students the importance of understanding childhood development. One aspect of this is the fact that young children interpret things literally and the notion of a joke is very definitely acquired by older children rather than understood by young children. Clearly I had not put my theory into practice.

Worlds apart

What is important to adults may have little to do with what is important in the world of children. The mother of a young girl with cystic fibrosis recounted to me the following story.

Picture two adults in the front seat of a car and three children in the back seat, chattering away. One of the three has cystic fibrosis and the other two are her cousins. They had been staying with their grandparents, the occupants of the front seat. Separate conversations were occurring in the front and the back seats until the discussion in the front seat moved to that traditional theme of how the children of today do not know how lucky they are. After a pause a little voice piped up from the rear saying, ‘It’s not as good as all that!’.

‘Oh really dear’, came the response from the front seat. These are always tense moments in a family where a child has a severe chronic illness. How should the grandparents respond to the probing questions about disability and premature death? How does one maintain the external appearance of composure at the same time as being very upset at having to discuss painful issues? Oblivious to the anxiety pervading the atmosphere in the front seat came a single and unexpected comment: ‘This morning at breakfast you stirred my Weetbix the wrong way’. MT

Reference

1. Larson G. The Far Side Gallery. Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 1984.