Innocence revisited – 38

Dr Andrew Black loses his innocence in an isolated part of Papua New Guinea.

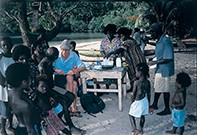

I am living and working at the Arawa Health Centre on Bougainville Island, Papua New Guinea, a large tropical volcanic island in the northern part of the Solomon chain. This island was the site of the world’s largest copper mine until discontent with the mine flared up into a conflict that lasted eight years. Since 1997, however, there has been a truce, and services and infrastructure are being restored gradually.

In Arawa, our theatre team consists of Andrew (the other doctor), Llane (a nurse from New Zealand who doubles as an anaesthetist), Jean (an outpatient department nurse who has learnt fast how to function as a theatre nurse), Elizabeth (an indispensable theatre nurse), and myself. We are faced daily with new challenges and have learned to value the art of improvisation. Similar to health workers in other developing countries, we are experiencing the time when medical science and technology were in their innocence, when diagnosis and treatment were primarily based on clinical judgement, not on a barrage of investigations.

My first burrhole

Not long ago, I was faced with my first opportunity to perform a burrhole evacuation, a classic part of medical education and training. The patient was a young boy who had fallen out of a tree and suffered a skull fracture. He had a probable enlarging intracranial haematoma and was deteriorating, but the nearest CT scanner and neurosurgeon were way beyond reach. I had to rely on my clinical judgement. It was a difficult situation: without intervention he would soon be dead, but I lacked the equipment to perform burrhole surgery.

With his parents’ consent, I drove to the Peace Monitoring Group to phone the medical section. The army doctor and a paediatric nurse came to review the boy, then departed to use the satellite phone to contact either the provincial hospital on neighbouring Buka Island or Australia for a neurosurgical opinion. They returned an hour later with a drill to use. ‘Phone’s out in Buka’, they reported. ‘The Australian neurosurgeon said drill.’

The drill was a proper drill for use in neurosurgery and the army doctor had recently used one on a patient in East Timor. We opened the scalp under IV sedation, using local lignocaine with adrenaline. The fracture extended from the occipitoparietal region down to the temporal bone and up again to the frontal bone. Making the burrhole was tricky, and the drill bit kept slipping. Eventually we got through the bone and white material began extruding – inflammatory material, we decided, not brain. The extradural haematoma underneath had coagulated, so we were forced to enlarge the hole with bone nibblers. After making a 4 by 3 cm opening, we excavated as much clot as possible, put in a drain and closed the scalp.

The patient’s left eye became reactive postoperatively, but as his coma lightened over the next days it became obvious that he had had ani ntracerebral haemorrhage or infarct. We didn’t need a CT scan to determine that; he had a left hemiplegia and a fixed dilated left pupil.

The young boy now has aspiration pneumonia, which is improving slowly, but I am saddened because my clinical judgement tells me that the boy is likely to have suffered severe brain damage.

A bladder fit to burst

Where medical facilities are sparse, we often have to deal with familiar problems in new ways. Recently I was faced with an unusual challenge. A man with urinary retention had somehow failed to have his indwelling catheter changed for four months. Now the catheter was blocked and so, I soon discovered, was the balloon. I couldn’t aspirate the liquid from the balloon or remove the catheter. All I could do was inject more water into the balloon. When I had injected 100 mL, his already full bladder was ready to burst. I quickly aspirated one litre suprapubically, and then returned to filling the balloon. Eventually, when I had injected 250 mL and was about to give up, the balloon burst, the man had a brief pain, and the catheter came out easily. For the record, it was a 20 French catheter with a 20 mL balloon.

Being a part of Bougainville

Life is never dull here. Many of the things that occur would be humorous if they were fictitious, but in fact they are very real. Bougainville may be an island paradise, but it is overflowing with children crying out for health care and education. I was able to come to Bougainville Island through Australian Volunteers Inter.national, which recruits doctors to work in developing countries throughout the world. My colleague, the other doctor (and the other Andrew) on the island, describes working here as the best job he will ever have. I describe it as the perfect challenge for any.one who feels that all of his or her skills need to be put into use. MT