Innocence revisited – 36

Two cases of poor doctoring have greatly influenced Professor Sir John Scott’s approach to clinical problems.

Learning from bad advice

To varying degrees, innocence remains with many of us throughout our lives. Others develop cynicism at an early age. Many great clinicians are remembered for their combinations of skill, understanding of people, and contributions to society generally. Such doctors generally manage to avoid the descent into cynicism, while learning from the series of surprises that human nature successively presents to them.

As an 18-year-old, I attended the compulsory medical examination for possible military service. At the time I was struggling with the mysteries of anatomy, physiology and biochemistry. A handsome, bronzed and extremely efficient young doctor examined me from top to toe. He scribbled as he worked and grunted from time to time. I had never been through such a procedure.

My cremasteric reflexes were powerful as he poked around my groin, ignoring my acute embarrassment. He seemed pleased with what he had found. ‘You’ve got a large varicocele – on the left side as usual – probably a bit on the other side too. It is most unlikely that you will ever be able to have children’.

The message came suddenly, but sank in slowly. I had no brothers and only one male cousin within what was quite a large extended family. I worried about the matter for over a year before going to the senior doctor in the student health service. He was a gentle, kindly man who listened thoughtfully to my tale of anxiety and embarrassment.

‘I am sorry you have had such unnecessary worry. You are the victim of a very bad piece of doctoring. I know a man who has lost one testis and has a large varicocele on the remaining side. He has six children and I am sure they are his’, he said with a grin.

In my innocence I didn’t quite understand the implications of that remark. Four children and eight grandchildren later, I still ponder on the worry the young doctor had inflicted upon me.

… from the inexperienced to the experienced

I had had a similar experience about two years earlier. I was nearing my peak as a swimmer when I was smitten by what would now be called glandular fever-like syndrome. I had been wrestling with the key issue of vocational choice. Barriers to medical school entry were high. Despite my intense fatigue, I battled on with my studies and made money in the holidays at the wool stores and on the wharves.

One night as I was leaving work, I leapt to get on to the slowly moving last tram. Simultaneously a massively built waterside worker did the same. I came off second best. My chest was extremely sore but I carried on at work. Eventually the pain led me to visit the quite distinguished, relatively senior, family GP. He knew, from my parents, about my career anxieties. He decided rapidly that my chest pain was ‘psychosomatic’. He even went to the lengths of giving me some local anaesthetic, making an incision and pretending that he had released some purulent material; this did not fool me.

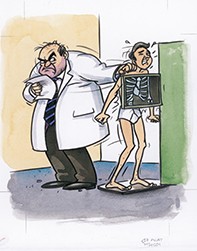

I persisted at work and with my complaints. The GP was clearly annoyed that his sleight of hand had not worked. He sent me off for an x-ray with a note carefully sealed in the envelope. The senior radiologist opened the envelope, read the note and scowled at me. He marched me before the machine and slapped my chest against a cold x-ray plate. I yelled. He made a derogatory comment.

Twenty minutes later he returned, obviously a bit flummoxed, but made no apology. He said the report would be sent to the GP. I had a fractured sternum and by the time I had the x-ray some callus was already visible. Understandably, I never reached my peak as a swimmer.

There were other incidents as well, but it was those two that greatly influenced my later approach to clinical problems. I had learned early on that there were wide discrepancies in the overall competence of colleagues, of all ages. They varied in terms of their ability to listen carefully and compassionately, and to proceed thoughtfully in their handling of the succession of human problems that they confronted. MT