Innocence revisited – 33

The tenacity of the human spirit is highlighted in Professor Sir John Scott’s recollections.

Doctors who endure the horrors of war immediately and savagely gain a perspective on human capacity for survival. Fortunately, most of us are denied such vivid learning. Much of our awareness of the tenacity of the human spirit, and of the survival capacity of the human body, is second-hand.

Surviving through ingenuity

During World War II, I worked on farms because labour was desperately short. I spent time with much older men, many of whom had served in World War I. On horseback we mustered sheep, working with dogs, and returned ‘home’ at night exhausted but deeply contented.

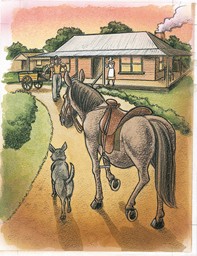

Jack owned one large station. He had lost his left arm below the elbow in Flanders in 1917. He had designed a crude prosthesis and had it made for himself. Jack was remarkably adept at tackling tasks which, theoretically, were beyond him. One day he was at the back of beyond using a knife to deal with footrot in some of his sheep. The knife slipped and he opened the femoral artery of his left groin. The wound was such that the artery stayed open. Jack was dying rapidly. He tore material off his shirt, happened to have a sack needle with him and managed somehow, using his teeth and right hand, to thread the needle, ligature the two ends of the femoral artery and loosely stitch the skin together. He managed to spur the horse into action, sending it plodding homewards alone. After a while his faithful dog understood that the primary canine duty was to go back to the homestead rather than stay with his injured master.

As dusk fell, the horse stumbled home, accompanied by the dog. A huge search was mounted in semi-darkness, and Jack was found, barely conscious. Sulfonamides had arrived, and probably deserve much credit, along with Jack’s own capacity for survival, such that the tale ended happily.

At an impressionable age I was greatly influenced by all aspects of this story; however, the men who had been in the war were not surprised by what Jack had done. Conversely, they were amazed that Jack did not develop gangrene and die over a miserable 10 to 12 days.

Doubting the prognosis

I had learned an important lesson that was reinforced later in my life. As a physician I looked after a naval officer who had been head of the Free French forces in the Pacific, and also his wife. They came down to visit me once or twice a year from New Caledonia. The Commander died first, followed by his wife. I was sad that a chapter had closed.

Several months later, a white-faced receptionist came into my office. I can still remember her words. ‘There is the remains of a man at the front desk demanding to see you’, she said. It was not her usual language. I went out and realised that the description was accurate.

The French military had sent the man to me with the Commander’s gold watch, which he had left to me in his will. With due ceremony the man transferred the bequest. With surprise, gratitude and hopefully some humility, I acknowledged the gift. He then turned to me and asked me to examine him. He explained that the French doctors had given him a prognosis and he wasn’t quite sure whether to trust them. He was one of the survivors of Dien Bien Phu. He had nothing but praise for General Giap’s North Vietnamese troops. They had treated this French survivor with dignity and great care. He had lost most of one hemithorax and one forearm and had wound scars over his abdomen and a shattered left lower leg. His face was grossly disfigured, and he had lost an eye. He had responded gradually to management provided by the North Vietnamese. He felt rather bitter about the bungles of the French campaign and did not wish to return to France. He was repatriated to New Caledonia.

I examined the man carefully and arranged for a chest x-ray. When I had the result I sat down with him. I knew enough French to converse reasonably efficiently. Sadly, I told him that I agreed with the prognosis he had been given about three months earlier. The scarring and distortion in his ‘good’ hemithorax was such that he had fully established cor pulmonale. His ECG showed massive right ventricular hypertrophy. As compassionately as I could, I explained that, although miracles had been achieved in his case, nothing further could be done. He accepted what I said calmly. He thanked me profusely for my trouble. His plane took him back to Noumea the next day. I checked up and found that he had died about six weeks later. I suspect he gave up, and who would fault him for that?

Surviving the impossible

Those of us who practise in the calmer territories away from the continual crises faced by the paramedics, the trauma surgeons and the ICU specialists may well carry throughout our professional lives a form of ignorance that may operate to the detriment of some patients, who have the capacity to survive the impossible. We need to remember this special group, while not striving too officiously to keep alive those to whom continued existence is not life as they or we would wish to know it.

Medicine never was and never will be an easy profession. MT