Innocence revisited – 35

Dr Eva Szego reflects on two sad cases in which her involvement as a GP was not easy.

The abortion

It was obvious from the beginning that Mrs Y was a determined woman. ‘I am three months pregnant and I want an abortion. Please help me, doctor’, she said without hesitation.

She was about 36 years old, a thin, pale woman who wore high heels and a high hairstyle to compensate for her small stature. ‘I cannot have this baby, not under any circumstances’, she said, after I had tried to persuade her to continue the pregnancy.

She was reluctant to tell me much other than a few basic facts: that she was a new immigrant, divorced with two teenage daughters; that she had to work and there was no future with the baby’s father.

It was 1965 when this happened, long before social security benefits became available for new immigrants and before single mother pensions were introduced. So I understood the difficulty of her situation.

I was deeply sorry to have to tell her that I was not able to help. Government agencies were enforcing the abortion law – abortions could only be performed if the mother’s life was in danger, and doctors who performed illegal abortions had been arrested or forced to close their surgeries. Only in the previous week, one of my patients was getting ready for an abortion when police had raided the premises, arrested the doctor, and sent the patient home.

Finally I said, ‘Some of my patients have gone to Sydney for an abortion. I could make enquiries about that, if you wish’.

‘I can’t afford it’, Mrs Y said, with tears in her eyes.

The next day she rang me at home, late at night.

‘I just had the abortion’, she said in a low voice.

‘Can I ask who did it?’

‘I did it!’

‘But how?’

‘I boiled a knitting needle and pushed it inside. A few hours later I had enormous cramps and aborted the baby.’

‘How do you feel now?’ I asked anxiously.

‘Now I’m all right.’

‘I want you to come to the surgery, straight away’, I begged her.

She reluctantly agreed. I put my daughter to bed, left the untidy kitchen and drove to my office, a 10-minute trip. On the way, I considered the dangers: serious bleeding resulting from retained products of conception, infection (severe or otherwise), and shock.

When I arrived, she was not there, even though she lived closer to the surgery than I did. As I waited, my anxiety soared. Had she fallen on the street? Was she bleeding to death?

Then the doorbell rang, bringing me back from my nightmarish visions. I rushed to the door. There she was, seemingly freshly bathed and smelling of cheap soap, dressed in her high heels and with her hair pinned up beautifully, smiling. As she undressed, I became conscious of my untidy hair and unchanged clothing.

‘You certainly did a good job’, I told her after the examination.

‘Your uterus is empty and the neck of the womb is closed, with very little bleeding. But I have to assume that some infection has taken place, and I need to treat you for that.’

So I treated her for three days with antibiotics, but our relationship was not friendly. I had not helped her, and therefore she was forced to perform that hateful act. After her last injection,

I never saw her again.

A slip of the tongue

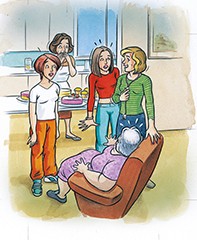

On my way to lunch one day, I got an urgent call from a family I knew well. As I entered their house, the pleasant smell of freshly baked cake reminded me that the younger daughter was soon to be married.

The patient was her future mother-in-law, a 66-year-old obese woman with hypertension and diabetes. She was seated in an easy chair, ashen faced, cold and clammy, with severe central chest pain. It was not difficult to diagnose a massive coronary occlusion.

As I attended to her and waited for the ambulance, I couldn’t help thinking how sad it all was because she clearly was not going to make it. I was also aware of my growing hunger.

Looking around, I could see anxious faces and beautiful cakes everywhere. I wanted desperately to lighten the moment.

Mentioning the wedding seemed the only way to ease the tension. So I turned to the bride-to-be and asked with a forced smile:

‘And when is the funeral?’

As it happened, three days after the wedding. MT