Wasting resources

Given the current overstretching of resources, Professor Sir John Scott questions how a present day complaints committee would view the following case.

Over the past 10 to 15 years, there has been increasing interest in the media, and within the community generally, in what goes wrong in our hospitals. Certainly, there is increasing concern at what are perceived to be cover-ups of previous misadventures. The public’s expectations of health worker performance have risen to levels that at times are unrealistic and unattainable in relation to the available resources and the limits of human capacity.

Health professionals often understate the public’s contribution to the problem. This general policy had a sound basis in the past when trust and faith in health professionals was a proportionately more significant element in determining the success or other wise of various interventions. Such arguments hold little or no water at present, even though a trusting confidence between patients’ families and health professionals is highly desirable for maximum efficacy of the various inter-relationships.

It is not politically correct to make light of untoward events these days. I wonder how a present day complaints committee would view and judge the following circumstances.

Wartime legacies

In the decade following the end of the Second World War there was a gross deficiency of medically qualified staff in most countries. All levels of staff did their best, but supervision was patchy, and those in the various levels of apprenticeship exhibited widely differing qualities of experience. Ex-service personnel returning to the health services had a maturity and level of experience well in advance of the emerging graduates from medical schools. They usually combined experience with commonsense tested in the school of hard knocks, and acted swiftly and decisively.

There were other legacies from wartime. One such was a veteran from the First World War who had acquired syphilis, presumably in France. He had a perforated palate as a result of a gumma. The perforation was hidden under his upper dental plate. He had lightning pains and was very fond of the relieving features of pethidine and morphine injections.

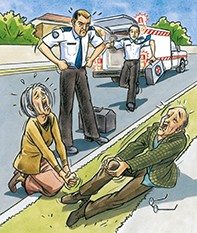

The veteran learned to dislocate a patella and lie at a roadside, pretending to be in acute pain as a result of a hit and run incident. His wife was part of the act, wailing and gesticulating on the sidelines. Successive waves of ambulance drivers and their assistants became wise to the act. If he did end up in a casualty department there was usually someone around who knew to take out his upper dental plate and expose the perforated palate. In those days a gumma scar thus exposed was synonymous with the probability of coincidental morphine addiction, in turn consequent upon the lightning pains of syphilitic neuropathy. He and his wife would promptly leave the hospital.

One extremely hot and humid Christmas Eve while working as a junior house surgeon, I was called upon to assist in casualty. The department was overburdened, and the staff were obviously harassed. The senior casualty officer had served in the Fleet Air Arm. He was competent, confident and irascible. He had met the First World War veteran before. When the veteran appeared amidst the chaos, the senior officer made his feelings known loudly, promptly and in naval language. The suffering patient with the ‘dislocated knee’ took a swing at the doctor, who swung back and knocked the patient unconscious. The doctor then had to admit the patient as a case of concussion. As a young doctor, full of good intentions and unsullied innocence, I was shocked by this sequence of events; my older colleagues were somewhat amused.

Abusing the system

Given the current gross overstretching of resources, if a complaints committee sat in judgment on a case such as this now, who would be found most at fault? The patient and wife were clearly habitual abusers of the system and thus wasting resources. The doctor in question might plea that he acted in self-defence, but who would believe him. Moreover, he contributed to further waste of resources through an unnecessary admission. Probably it was better then that the public knew nothing about it.

Would the public benefit from exposure of such a situation today? A doctor in such a case would undoubtedly have had a better lawyer than either the patient or the local authority. What do you think? MT