Pneumococcal vaccinations in Australia: current recommendations and beyond

Pneumococcal vaccines are effective in protecting against disease. They are recommended in Australia for young children, older people, Indigenous Australians and those at increased risk of disease, and funded under the National Immunisation Program for many of these groups. Clinicians should be aware of the available vaccine types and the current recommendations to effectively advise about and administer vaccines to those who will benefit most while also being abreast of the latest developments in this field.

Note

This is an online update of the original version of this article that was published in the Supplement of the August 2022 issue of Medicine Today. This update was prepared for World Immunization Week 2024.

Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) is the severe form of pneumococcal disease and is a nationally notifiable disease in Australia. Although rates of pneumococcal infections declined substantially when the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions were in place, they have since re-emerged to pre-pandemic levels. In Australia, pneumococcal vaccination is recommended for young children, older people, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and at-risk cohorts, and is funded for most of these groups under the National Immunisation Program (NIP). This article gives an overview of the pneumococcal vaccines available, including new pneumococcal vaccines that have become available recently, and describes the current pneumococcal vaccination recommendations for Australians.

Pneumococcal disease

Pneumococcal disease is caused by the encapsulated Gram-positive coccus Streptococcus pneumoniae, with pneumococcal disease responsible for 14% of deaths in children under 5 years of age in 2019 globally.1 IPD is characterised by the presence of S. pneumoniae in sterile body sites, including blood and cerebrospinal, pleural, peritoneal and joint fluid, causing severe disease.2 Noninvasive pneumococcal disease typically presents as localised mucosal infections that are usually less clinically serious and more common than IPD, such as otitis media, often seen in children.3 The most common adult presentation of IPD is bacteraemic pneumonia; however, most community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia cases are noninvasive.4 In most cases, S. pneumoniae resides in the nasopharynx, leading to asymptomatic carriage, which can be a precursor to disease and an important transmission factor.5 Over 100 unique pneumococcal serotypes have been identified so far based on the polysaccharide capsule of S. pneumoniae, which is an important virulence factor, with vaccines targeting serotypes that commonly cause disease.6

Pneumococcal disease in Australia

IPD became nationally notifiable in 2001 and there were 2267 notifications in 2023, 16% of which were in children aged younger than 5 years and 35% in adults 65 years or older.7 IPD notification rates are consistently higher among Indigenous Australians than non-Indigenous Australians.8 During the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of IPD in both adults and children decreased internationally, mainly because of public health restrictions resulting in reduced circulation of pneumococcal and other infectious agents. The reduced testing capacity and healthcare presentations may also have contributed to this observed decline.9,10 However, the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions has seen the resurgence of IPD to pre-pandemic levels with broadly similar serotype epidemiology.7

Pneumococcal vaccine types

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) involve the conjugation of multiple selected pneumococcal polysaccharides to a protein. This protein carrier conjugation converts the pneumococcus polysaccharide to a T cell-dependent antigen that induces immune memory and results in a robust, high-quality immune response, sufficient to prevent pneumococcal disease, including in infants, together with the ability to reduce carriage of the vaccine serotypes.11,12 In comparison, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines (PPVs) generate antibodies against pneumococcal disease alone, producing relatively short-lived immunity, and are considered to have no effect on pneumococcal carriage.13 Pneumococcal vaccines currently available in Australia are a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (13vPCV), a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (15vPCV), a 20-valent pneumococcal vaccine (20vPCV) and a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (23vPPV).

Current pneumococcal vaccine recommendations

In Australia, all adults aged 70 years and older are offered a dose of the 13vPCV for free through the NIP.14 For children, the NIP schedule is three doses of 13vPCV at ages 2, 4 and 12 months (2+1 schedule).15 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and those with certain underlying risk conditions are recommended to have the adult vaccine doses at a younger age, as well as additional doses of the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (23vPPV). This is because of their increased risk for pneumococcal disease, with a considerable proportion caused by extra serotypes in 23vPPV. The Figure summarises current pneumococcal vaccine recommendations for each target population. Although 13vPCV and 23vPPV are the only pneumococcal vaccines offered free to eligible Australians through the NIP, there are now recommendations for two other higher valency vaccines (15vPCV and 20vPCV) as nonpreferential alternatives to 13vPCV, but only through private prescription.

For children with medical risk conditions and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in certain states and territories, four doses of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (13vPCV or 15vPCV) at 2, 4, 6 and 12 months of age (3+1 schedule) are recommended; only 13vPCV is funded through the NIP.

Children and infants can receive their dose of pneumococcal vaccine (PCV or 23vPPV) coadministered with other routine childhood vaccines, including inactivated influenza vaccines. However, parents and caregivers should be made aware of a small increased risk of fever when 13vPCV and influenza vaccinations are given together. Pneumococcal vaccines (PCV or 23vPPV) can be coadministered with herpes zoster vaccine (Shingrix), COVID-19 vaccines and inactivated influenza vaccines in adults.14

People with conditions that put them at increased risk of pneumococcal infection are also recommended to receive pneumococcal vaccines. Vaccination for people with most (but not all) of these high-risk conditions is funded under the NIP and is summarised in the Box. All current recommendations by the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) for pneumococcal vaccines are published in the Australian Immunisation Handbook (https://immunisationhanbook.health.gov.au).14

Changes to the pneumococcal vaccination program

The current recommendations and funding of 13vPCV for adults were introduced in July 2020.16 This updated schedule no longer recommended the 23vPPV for healthy adults aged 70 years or older, and instead recommends a single dose of 13vPCV for this cohort. Under the updated recommendations, the 23vPPV is reserved for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults aged 50 years or older and adults with underlying risk conditions only, following a dose of 13vPCV in both. The key evidence leading to the decision to use 13vPCV in adults came from the results of a randomised controlled trial that showed 13vPCV was effective against all pneumococcal pneumonia, including less severe but more common nonbacteraemic pneumonia.17 Serotype epidemiology of pneumococcal disease in adults in Australia showed that most disease from the additional serotypes contained in 23vPPV occurred in Indigenous adults and individuals with pre-existing risk conditions; therefore, 23vPPV doses are now offered to those groups only.

Alongside this change, two doses of 23vPPV were added to the existing recommended 3+1 schedule of 13vPC for Aboriginal children living in the Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia to provide broader serotype protection. In 2018, the PCV schedule was changed, from the longstanding 3+0 to the current 2+1, for most children in Australia to address the waning immunity from the second year of life.18,19 Early assessment of this change shows that the expected reduction in breakthrough cases of IPD in older children is occurring.20

Since 2021, the two PCVs with expanded serotypes, Vaxneuvance (15-valent PCV by Merck) and Prevenar20 (a 20-valent PCV by Pfizer) were licensed by the TGA for use in adults and children. Both vaccines have also been assessed by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee and approved to be listed on the NIP for eligible children and adults.21,22

What’s next for pneumococcal vaccination?

As current pneumococcal vaccines target specific serotypes, infections with certain nonvaccine serotypes of S. pneumoniae may occur when those serotypes have a competitive advantage in nasopharyngeal carriage, leading to some ‘serotype replacement’ disease.23 The development of the vaccines with expanded serotypes (known as the higher valency vaccines) aims to maintain and optimise pneumococcal disease prevention by covering these emerging and common residual serotypes.

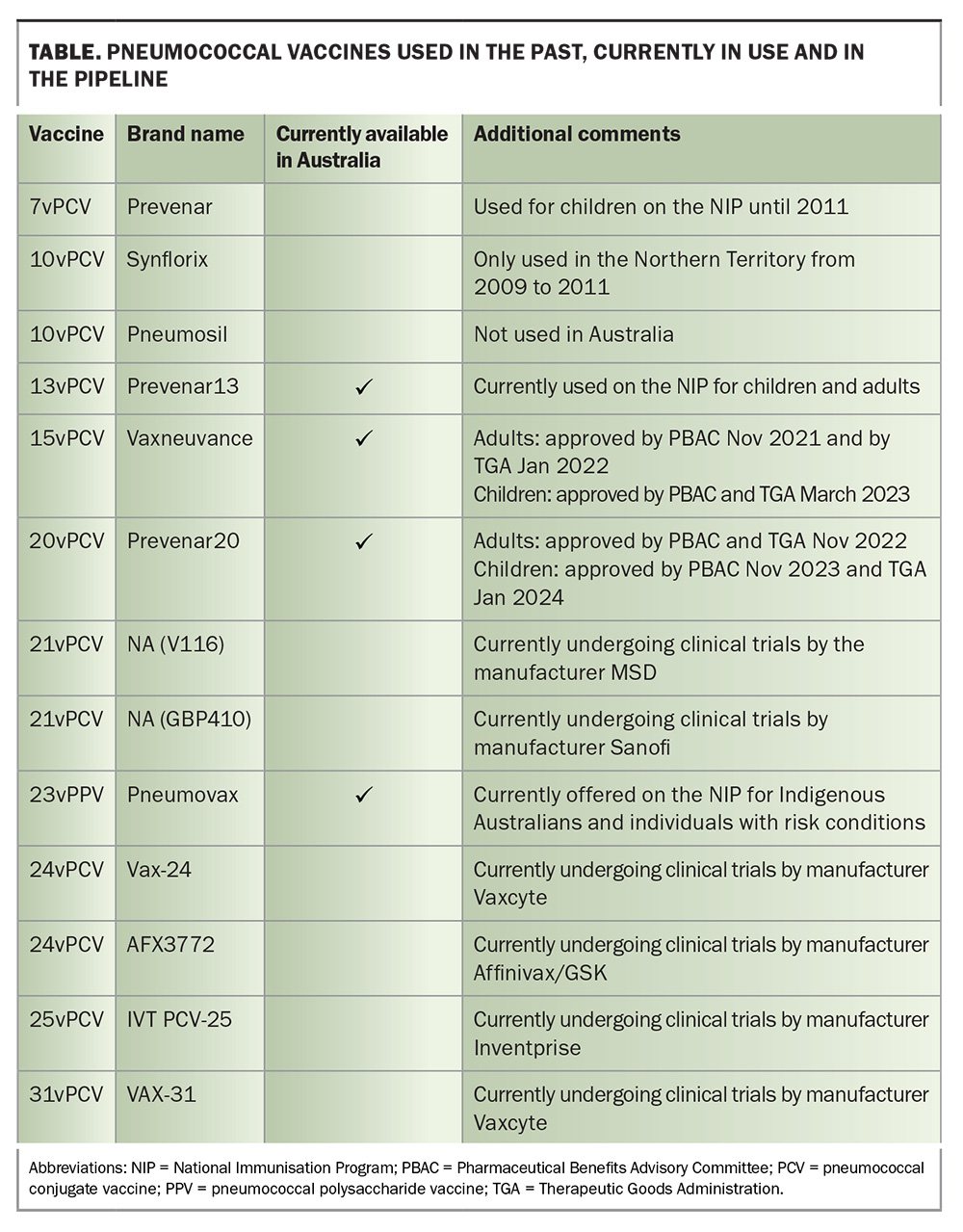

Previous pneumococcal conjugate vaccines used in Australia have been superseded by vaccines with an expanded serotype spectrum (e.g. 13vPCV replacing 7vPCV in 2011).24 The 15vPCV and 20vPCV cover some of the main serotypes that are causing residual IPD following several years of 13vPCV use. There is a 21-valent PCV (V116PCV by Merck) that is being developed as an adult formulation, which already has several trials completed.25,26 PCVs with even greater number of serotypes, some using novel vaccine platforms, are also in the pipeline (e.g. a 25-valent PCV and a 31-valent PCV candidate).27 The Table summarises important details of pneumococcal vaccines previously used in Australia, those currently part of the NIP and the higher valency vaccines currently available or under development.

The ATAGI is currently undertaking a comprehensive review to determine the optimal pneumococcal vaccination program for Australians considering all the available pneumococcal vaccines.

Conclusion

In Australia, the recommendations for pneumococcal vaccination are based on vaccine characteristics and individuals’ IPD risk factors, including age, Indigenous status, state or territory of residence, the presence of underlying conditions and previous pneumococcal vaccination history. It is important for immunisation providers to be aware of the differences between pneumococcal vaccine types, their dose schedules and approved population groups, as well as changes to recommendations, with potential inclusion of new vaccines. Understanding the differences between pneumococcal vaccines and potential vaccination program changes with the availability of new vaccines will provide easier implementation of current pneumococcal vaccination recommendations. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Jayasinghe holds an emerging leadership investigator grant from the NHMRC. Ms van Eldik and Dr Norman: None.

References

1. World Health Organization. Pneumonia. Geneva: WHO; 2021. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/pneumonia (accessed April 2024).

2. Tuomanen EI, Austrian R, Masure HR. Pathogenesis of pneumococcal infection. N Engl J Med 1995; 332: 1280-1284.

3. Eskola J, Kilpi T, Palmu A, et al. Efficacy of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against acute otitis media. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 403-409.

4. Drijkoningen JJ, Rohde GG. Pneumococcal infection in adults: burden of disease. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20(Suppl 5): 45-51.

5. Jochems SP, Weiser JN, Malley R, Ferreira DM. The immunological mechanisms that control pneumococcal carriage. PLoS Pathog 2017; 13: e1006665.

6. Ganaie F, Saad JS, McGee L, et al. A new pneumococcal capsule type, 10D, is the 100th serotype and has a large cps fragment from an oral streptococcus. mBio 2020; 11: e00937-20.

7. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System: National Communicable Disease Surveillance Dashboard. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2024. Available online at: https://nindss.health.gov.au/pbi-dashboard/ (accessed April 2024)

8. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Pneumococcal disease in Australia. Canberra: AIHW; 2018. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/0e959d27-97c9-419c-8636-ecc50dbda3c1/aihw-phe-236_Pneumococcal.pdf.aspx (accessed April 2024).

9. Brueggemann AB, Jansen van Rensburg MJ, Shaw D, et al. Changes in the incidence of invasive disease due to Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis during the COVID-19 pandemic in 26 countries and territories in the Invasive Respiratory Infection Surveillance Initiative: a prospective analysis of surveillance data. Lancet Digit Health 2021; 3: e360-e370.

10. Dirkx KKT, Mulder B, Post AS, et al. The drop in reported invasive pneumococcal disease among adults during the first COVID-19 wave in the Netherlands explained. Int J Infect Dis 2021; 111: 196-203.

11. Pichichero ME. Protein carriers of conjugate vaccines: characteristics, development, and clinical trials. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013; 9: 2505-2523.

12. Rose MA, Schubert R, Strnad N, Zielen S. Priming of immunological memory by pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children unresponsive to 23-valent polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2005; 12: 1216-1222.

13. Daniels CC, Rogers PD, Shelton CM. A review of pneumococcal vaccines: current polysaccharide vaccine recommendations and future protein antigens. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2016; 2: 27-35.

14. Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation. Pneumococcal disease. In: Australian Immunisation Handbook. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; 2018. Available online at: https://immunisationhandbook.health. gov.au/contents/vaccine-preventable-diseases/pneumococcal-disease (accessed July 2022).

15. Bonten MJ, Huijts SM, Bolkenbaas M, et al. Polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against pneumococcal pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1114-1125.

16. Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation. ATAGI clinical advice on changes to recommendations for the use and funding of pneumococcal vaccine for 1 July 2020. Canberra, ATAGI; 2020. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/atagi-clinical-advice-on-changes-to-recommendations-for-pneumococcal-vaccines-from-1-july-2020 (accessed April 2024).

17. Australian Government Department of Health. National Immunisation Program Schedule. Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia; 2022. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/immunisation/when-to-get-vaccinated/national-immunisation-program-schedule (accessed April 2024).

18. Blyth C, Jayasinghe S, Andrews R. A rationale for change: an increase in invasive pneumococcal disease in fully vaccinated children. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 7: 680-683.

19. Jayasinghe S, Chiu C, Quinn H, Menzies R, Gilmour R, McIntyre P. Effectiveness of seven and thirteen valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in a schedule without a booster dose: a ten year observational study. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67: 367-374.

20. Public Health Association of Australia. Blyth CC. Looking back, looking forward: vaccine preventable disease control in Australia. Presented at: Communicable Disease and Immunisation Conference 2022.

21. National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NCIRS). Significant events in pneumococcal vaccination practice in Australia. Sydney, NCIRS; 2024. Available online at: https://ncirs.org.au/sites/default/files/2024-03/Pneumococcal_History%table.pdf (accessed April 2024).

22. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) meeting outcomes November 2021 PBAC meeting. Canberra, PBAC; 2021. Available online at: https://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/pbac-outcomes/2021-11/pbac-web-outcomes-11-2021.pdf (accessed July 2022).

23. Weinberger DM, Malley R, Lipsitch M. Serotype replacement in disease after pneumococcal vaccination. Lancet 2011; 378: 1962-1973.

24. Chiu C, McIntyre P. Pneumococcal vaccines – past, present and future. Aust Prescr 2013; 36: 88-93.

25. National Institute of Health US National Library of Medicine. Safety and immunogenicity of V116 in pneumococcal vaccine-naïve adults (V116-003, STRIDE-3). Maryland, USA, NIH; 2023. Available online at: https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05425732 (accessed April 2024)

26. Platt H, Omole T, Cardona J, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a 21-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, V116, in health adults: phase 1/2, randomised, double-blind, active comparator-controlled, multicentre, US-based trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2023; 23: 233-246.

27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting February 2024: Pneumococcal Vaccines. Atlanta, USA, 2024. Available online at: (accessed April 2024).