Major study reveals two-thirds of people who suffer childhood maltreatment suffer more than one kind

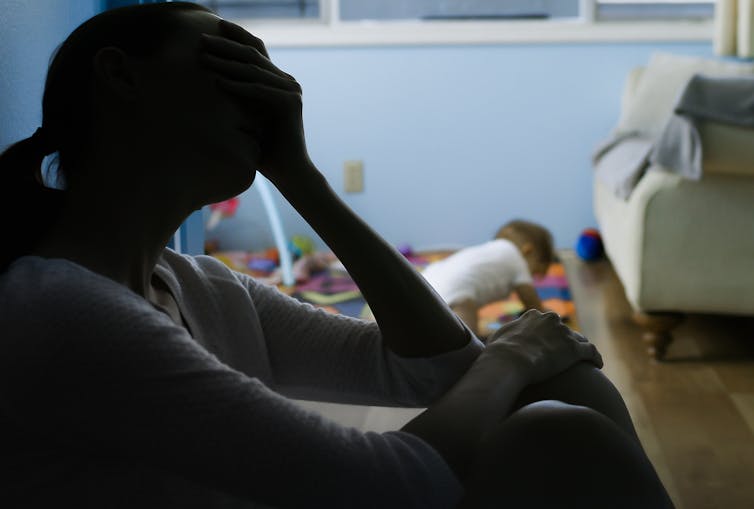

The following story deals with reports of childhood maltreatment, including neglect and physical and sexual abuse.

This week, we released results from the Australian Child Maltreatment Study. It is the first national survey of the population aged 16 years and older about their experiences of child maltreatment. It’s also the first study globally to examine combined exposure to all five specific domains of child maltreatment and associated family risk factors for multiple types of child maltreatment.

We surveyed 8,500 randomly selected Australians aged 16 and over. We found 8.9% had experienced neglect; 28.5% sexual abuse; 30.9% emotional abuse; 32.0% physical abuse; and 39.6% exposure to domestic violence.

While it is shocking to learn more than three in five Australians have experienced child abuse or neglect, there’s more to consider. Many Australians have experienced more than one type. This is critical to understanding the burden of maltreatment and its impacts across life.

What does ‘maltreatment’ mean?

We explored five types of maltreatment that participants experienced up to age 18:

- physical abuse: the use of force likely to cause injury, harm, pain, or breach of dignity

- sexual abuse: contact and non-contact non-consensual sexual acts inflicted on a child by another person (adult or child)

- emotional abuse: acts by parents or carers that convey to a child they are worthless, flawed, unloved, unwanted

- neglect: when parents or carers repeatedly fail to provide the basic developmentally appropriate necessities of life such as food, shelter or health care

- exposure to domestic violence: hearing or seeing acts of violence towards parents or carers in the home.

For Australians who experience any childhood maltreatment, experiencing more than one type is the “typical” experience (almost two out of three who report any maltreatment). Our data show Australian children are more likely to experience multi-type maltreatment (reported by 39.4% of our participants) than single-type maltreatment (22.8%).

Four family factors that double the risk

Four types of family adversity each more than doubles the risk of multi-type maltreatment:

- parental separation/divorce

- living with someone who is mentally ill, suicidal, or severely depressed

- living with someone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs

- family economic hardship.

Girls are more likely to experience multi-type maltreatment (43.2%) than boys (34.9%). The highest prevalence was for those with diverse gender identitites: two-thirds experienced multi-type maltreatment (66.1%).

Although harrowing, our data also reported rates of physical and sexual abuse (in some contexts) are showing some recent declines. One way we determined this was that the younger participants in our study (aged 16–24) had a lower prevalence of sexual abuse (25.7%) than the full sample (28.6%). Similarly, fewer participants aged 16–24 reported physical abuse (28.2%) than all those surveyed (32.0%).

This suggests current policies might be helping. But the continued high rates of most forms of maltreatment, and of experiencing multiple types, shows the need for greater investment in prevention to stop harm from occurring in the first place.

Adults with a history of childhood maltreatment suffer more often from depression and cardiometabolic disease than their non-exposed peers, reports a study published in @BMCMedicine. https://t.co/8og0RWqbEs

— BMC (@BioMedCentral) March 22, 2023

Read more: Our child protection system is clearly broken. Is it time to abolish it for a better model?

We need to stop focusing on single types of abuse

Our view of child maltreatment has typically focused on the experience of individual types, without considering the possibility of their overlap. We now know multi-type maltreatment is common.

We also found girls were at greater risk of most forms of child maltreatment, but particularly multiple types of maltreatment and their associated health consequences. So, as well as population-wide strategies, we need to put extra effort into ensuring the safety of girls, and those who are gender diverse.

We can approach childhood maltreatment on three fronts:

1. Prevention

Child protection services are overwhelmed, so simply asking them to do more is destined to fail. Instead, we need to shift our focus to primary prevention strategies across the community. Global evidence shows violence against children is preventable.

Our attitudes towards children must change, to value them, uphold their rights, and prioritise their safety.

Parents and caregivers need access to evidence-based supports to improve parenting skills, provide safe environments for children and young people, to stop maltreatment from happening in the first place.

Australia’s strategies for creating child-safe organisations to prevent institutional child sexual abuse needs to be adapted for creating safety for children in the home too. Parents could “assess” the suitability of adults to care safely, to understand and address situational risks (depending on the places, the people, and the activities involved), to equip their children with knowledge about sexuality and skills regarding consent and respect, and be prepared to listen and respond to all safety concerns – including harmful sexual behaviour from other children.

National strategies for addressing sexual abuse, child maltreatment and domestic and family violence need to recognise the high likelihood of exposure to multiple harm types. Child maltreatment prevention efforts need to link with points of vulnerability, including when parents separate, suffer mental illness, substance misuse, economic hardship, or family violence.

2. Responding to adversity

When we see families struggling, we need to keep the focus on children as well as their parents. When working with families who are going through adversities – including mental illness, addiction, poverty, family violence, or separation – we need to ask child-centred questions about parents’ care responsibilities.

If we pay closer attention to what’s going on in young people’s lives, we can identify vulnerability early. We can gently convey information about the increased risk of multiple types of maltreatment. And we can provide families with support that works, tailored to their circumstances and challenges.

3. Better treatment for adult survivors

Clinicians need better training to identify and respond to risks.

When working with clients struggling with mental health issues or substance misuse, practitioners should recognise this group is likely to be primarily victim-survivors of multiple forms of child maltreatment.

Teachers, doctors, therapists, parents and carers should learn about how child maltreatment impacts on health throughout life.

Prevention, protection, and treatment services must coordinate to create safety and recovery from all forms of child maltreatment, particularly when they occur in combination. Our results make it clear we need urgent action.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or contact Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article, published on April 3, 2023

Disclosure statement

Daryl Higgins receives funding from the Australian Research Council, the National Health and Medical Research Council and a range of government departments, agencies, and service providers. He is a Chief Investigator on the Australian Child Maltreatment Study, which is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grant (APP1158750). The ACMS receives additional funding and contributions from the Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; the Department of Social Services; and the Australian Institute of Criminology The lead Chief Investigator on the ACMS is Ben Mathews, from QUT. Other Chief Investigators are: Rosana Pacella, James G. Scott, David Finkelhor, Franziska Meinck, Holly E. Erskine, Hannah J. Thomas, David Lawrence & Michael P. Dunne. Thanks to Divna M. Haslam & Eva Malacova for assistance with project management and data analysis.Opinions expressed in Something Borrowed are those of the original authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors, the Editorial Board or the Publisher of Medicine Today.

![]()