A polycyclic scaly eruption on the trunk and shoulders

Test your diagnostic skills in our regular dermatology quiz. What is the cause of this erythematous, scaly eruption on sun-exposed areas?

Case presentation

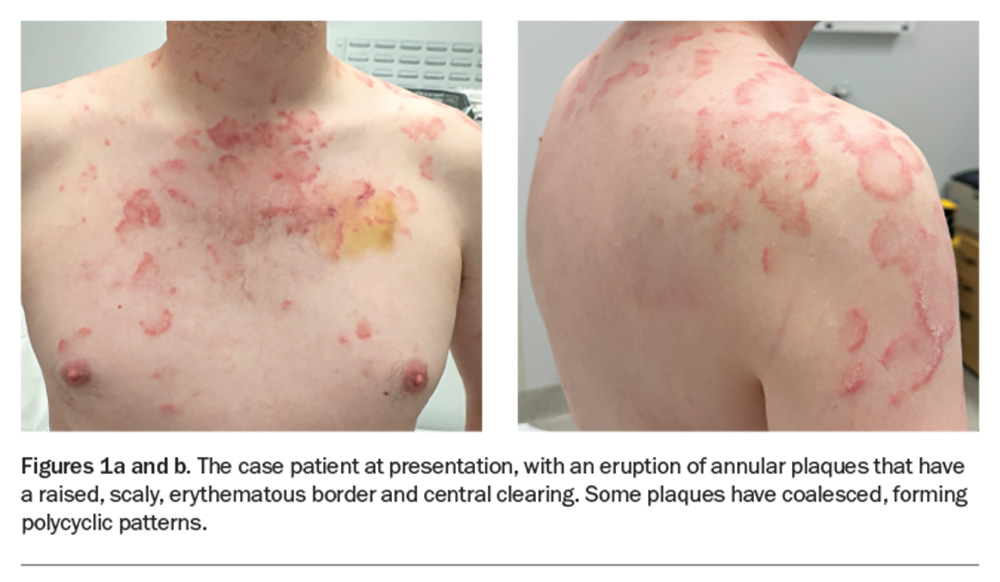

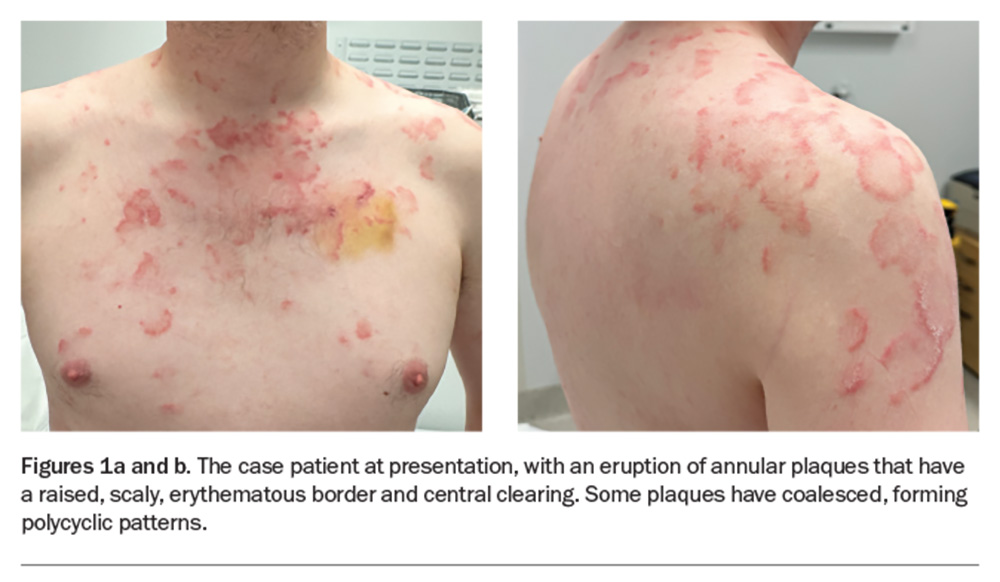

A 36-year-old man presents with a four-month history of annular plaques on his upper back, chest and shoulders (Figures 1a and b). The eruption is asymptomatic and not migratory, but is aggravated with sun exposure. He is otherwise well and does not have any systemic symptoms.

The patient’s medical history includes attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, allergic rhinitis, slow gut motility and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, for which he takes methylphenidate, prucalopride and esomeprazole. Six months ago, he took a 10-week course of oral terbinafine for a fungal toenail infection.

On examination, annular plaques are noted with central clearing and a raised border that is erythematous and scaly. The plaques coalesce to form polycyclic patterns on the upper chest and shoulders. The eruption is symmetrically distributed on the sun-exposed areas of the upper trunk and proximal arms but the face is spared. There is no involvement of other skin or the mucous membranes. Inspection of the feet reveals chronic onychomycosis of the left hallux toenail.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnosis include the following.

Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis is a dermatophyte infection usually caused by anthropophilic species of dermatophytes, most commonly Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton tonsurans, and less often by zoophilic species, such as Microsporum canis.1 It typically presents as a solitary, well-demarcated patch or plaque that is mildly erythematous, annular and scaly with associated mild pruritus.2 Over time, multiple lesions may develop and can coalesce to become polycyclic. Tinea corporis is also known as ‘ringworm’, a misnomer that describes how the annular lesions often spread centrifugally and form a central clearing with a raised, active, scaly border (‘ring’) on the leading edge.3

Tinea corporis is generally a clinical diagnosis. If there is any doubt then a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation of skin scrapings can be taken for microscopic examination, with the diagnosis confirmed by visualising dermatophyte hyphae as bright, linear and/or branching structures.4 Fungal culture of the skin scrapings can provide identification of the causative organism. Skin biopsy reveals foci of parakeratosis with epidermal acanthosis, spongiosis and neutrophils in the upper epidermis, and oedema and chronic inflammatory changes in the dermis.5 Periodic acid-Schiff or Grocott-Gömöri’s methenamine silver staining showing septate branching hyphae is diagnostic.

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, whose eruption began with multiple lesions, rather than as a solitary lesion that spread over time. Furthermore, microscopic examination of KOH preparation of skin scrapings did not reveal branching hyphae.

Granuloma annulare

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a cutaneous, noninfectious granulomatous disease that is benign and often self-limiting. It occurs in all ages but is more common in females and people under the age of 30 years.6 The aetiology is unknown but has been thought to be associated with a triggering event, including infections (e.g. HIV, hepatitis B and C, herpes zoster, Epstein-Barr virus infections), autoimmune conditions, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, malignancy, skin trauma (e.g. insect bites, tattoos), Mantoux testing for tuberculosis, sun exposure, vaccinations and certain medications (e.g. allopurinol, NSAIDs, amlodipine, quinidine).7-9

GA usually presents as erythematous annular plaques or papules, which may be solitary or multiple. The surface of the lesions is smooth, and the central area may be slightly depressed.10 GA is usually asymptomatic but some people experience mild pruritus or tenderness.

The most common form of the disease is localised GA (75 to 85% of cases), which frequently occurs over the bony prominences of the hands and arms, but may be distributed anywhere on the limbs or trunk.6,11 Up to 15% of patients will have more than 10 lesions.10 Generalised GA (8 to 15% of cases) presents as widespread flesh-coloured or erythematous small papules in an annular configuration; this form usually presents around the skinfolds of the trunk and proximal extremities. Other forms of GA, including subcutaneous, perforating and actinic forms, are far more rare.

GA is usually diagnosed clinically, but if there is any doubt then a skin biopsy may be performed. Histopathology usually reveals necrobiotic dermal granulomas, surrounded by histocytes and lymphocytes.12

For the case patient, the raised borders of the lesions were scaly, rather than smooth, and the distribution was not typical of GA.

Erythema annulare centrifugum

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) directly translates to red (erythema), ring-shaped (annulare) and spreading outwards with central clearing (centrifugum). The cause of EAC is unknown but it is classified as a hypersensitivity reaction and is associated with various underlying conditions, including infections (fungal, bacterial, parasitic and viral), autoimmune conditions, pregnancy, endocrinopathies, hypereosinophilic syndrome and various foods and medications.13 EAC may also occur as a paraneoplastic phenomenon, typically preceding a clinical diagnosis of malignancy, known as paraneoplastic erythema annulare centrifugum eruption (PEACE).14

EAC usually starts as small, mildly erythematous papules that gradually enlarge over several weeks to form annular or arciform plaques with central clearing.15 Classically, the lesions have a raised outer edge and a trailing, inner rim of scale. As the lesions enlarge, they may coalesce and form polycyclic or serpiginous patterns. The eruption may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic. EAC most commonly affects the proximal limbs and buttocks but can occur in any location on the body, although the palms and soles are typically spared.15

If the characteristic trailing, inner rim of scale is present then EAC may be diagnosed clinically. It can be confirmed by skin biopsy, which shows the typical features of an infiltrate of histiocytes and lymphocytes in a well-demarcated perivascular arrangement.16

For the case patient, the history of the skin eruption was not consistent with EAC because the lesions did not start as papules that enlarged over several weeks. More-over, the plaques did not have inner rims of scale.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

This is the correct diagnosis. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), a subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, is a photosensitive, erythematous eruption that usually presents as a papulosquamous eruption symmetrically distributed on sun-exposed areas, such as the neck, trunk, shoulders and extensor arms, but usually sparing the face.17 Lesions include annular plaques with raised, scaly, erythematous borders and central clearing, as seen for the case patient (Figures 1a and b). Vesicles, bullae and crusting may also be present.

The aetiology of SCLE involves a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental factors. It can affect people of any age, sex and ethnicity, but is most common in middle-aged women. SCLE occurs in around 10% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and is also associated with other autoimmune diseases, most commonly Sjögren’s syndrome.18

The most common precipitating factor for SCLE is sunlight exposure, which causes immune dysregulation and increased expression of Ro/SSA antigens on the surface of keratinocytes binding to auto-antibodies, leading to the disease.19 Around 20 to 40% of cases are drug-induced – the common offending agents include thiazide diuretics, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, terbinafine, antihistamines, beta-blockers, anticonvulsants, statins, chemotherapy agents and immunomodulators such as TNF-alpha inhibitors.20 The responsible drug can be difficult to deduce given the variation in incubation times between its commencement and the onset of the skin eruption (days to years). There have also been increasing case reports of SCLE associated with malignancies.21

SCLE is usually a clinical diagnosis. When in doubt, skin biopsies for histopathology and direct immunofluorescence testing can be performed. Haematoxylin-eosin, Alcian blue and periodic acid Schiff stains may help to clarify the histological features of SCLE for diagnosis – these include vacuolisation of the basal keratinocyte layer, perivascular inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate and increased dermal mucin.22 Direct immunofluorescence reveals granular deposition of immunoglobulin along the dermal-epidermal junction in around two-thirds of patients (positive lupus band test).

A thorough assessment for features of SLE should be conducted, given its strong association with SCLE. At a minimum, this includes a comprehensive history and physical examination for symptoms and signs of SLE and urinalysis. Investigations might include: a full blood count; electrolyte, urea and creatinine levels; and testing for autoimmune markers (antinuclear antibody [ANA], anti-double stranded DNA [anti-dsDNA], extractable nuclear antigen [ENA] antibodies including anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB, and complement levels C3 and C4). Most patients with SCLE fulfil more than four of the American Rheumatism Association criteria for SLE.18

Management

The cornerstone of SCLE management is diligent sun protection, with use of daily broad-spectrum sunscreen (ideally a physical blocker with zinc oxide or titanium dioxide), broad-brimmed hats and sun-protective clothing, and patients should be advised to minimise sun exposure where possible.23 If drug-induced SCLE is suspected, the causative medication should be ceased.

First-line pharmacological therapy involves topical corticosteroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus 0.1% or pimecrolimus 1%), applied two to three times daily to affected areas.24 If the condition is severe or oral therapy is inadequate, first-line oral treatment is hydroxychloroquine (6 to 6.5 mg/kg bodyweight daily), an antimalarial medication with photo-protective and anti-inflammatory properties. Around 25% of cases do not respond to hydroxychloroquine and another oral agent may be added – these include dapsone, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine.25 Cigarette smoking potentiates the disease and may also render hydroxychloroquine less effective, so it is crucial that patients who smoke be given advice about cessation.26

Patients generally respond well to treatment, although some may experience flares during warmer weather, when patients often expose more skin to UVA radiation in daylight hours.27 Fortunately, the eruption is nonscarring and often resolves with postinflammatory hypopigmentation that improves with time.

About 10 to 15% of patients with SCLE will later develop SLE.18 Therefore, it is important that patients with SCLE have routine follow-up assessments for neurological, renal and cutaneous involvement.

Outcome

The case patient was referred to a dermatologist. Investigations were arranged, including blood tests for autoimmunity, which returned a positive result for ANA (titre 1:320), Ro/SSA antibodies (Ro-60 and Ro-52) and La/SSB antibodies. The results of his other blood tests were unremarkable.

Two 4 mm punch biopsies were performed (one specimen placed in formalin for histopathology and another in saline-soaked gauze for direct immunofluorescence testing). Histological examination revealed scattered apoptotic keratinocytes, mild spongiosis, and superficial and perivascular chronic dermal inflammatory infiltrate with negative immunofluorescence. Given the strong clinical suspicion for SCLE, an Alcian blue stain was requested; this showed moderately increased dermal mucin, which confirmed the diagnosis.

The diagnosis of SCLE was communicated to the patient, with terbinafine being the likely precipitating cause. General management measures were explained carefully, including the need for diligent sun protection and awareness of the UV index. He was prescribed a potent topical corticosteroid (betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% ointment) to be applied twice daily to affected skin. A six-week follow-up appointment was arranged to assess his response to treatment and consideration of oral hydroxychloroquine. Regular follow-up with his GP was advised, as a significant number of patients with SCLE develop SLE. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Gupta AK, Chaudhry M, Elewski B. Tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea nigra, and piedra. Dermatol Clin 2003; 21: 395-400.

2. Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, Hon KL. Tinea corporis: an updated review. Drugs Context 2020; 9: 2020-5-6.

3. Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Stone MS. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician 2014; 90: 702-710.

4. Richardson MD. Diagnosis and pathogenesis of dermatophyte infections. Br J Clin Pract Suppl 1990; 71: 98-102.

5. Park YW, Kim DY, Yoon SY, et al. ‘Clues’ for the histological diagnosis of tinea: how reliable are they? Ann Dermatol 2014; 26: 286-288.

6. Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician 2006; 74: 1729-1734.

7. Studer EM, Calza AM, Saurat JH. Precipitating factors and associated diseases in 84 patients with granuloma annulare: a retrospective study. Dermatology 1996; 193: 364-368.

8. Dahl MV. Granuloma annulare. In: Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in general medicine. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003: 980-1010.

9. Voulgari PV, Markatseli TE, Exarchou SA, Zioga A, Drosos AA. Granuloma annulare induced by anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67: 567-570.

10. Rubin CB, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: a retrospective series of 133 patients. Cutis 2019; 103: 102-106.

11. Barbieri JS, Rodriguez O, Rosenbach M, Margolis D. Incidence and prevalence of granuloma annulare in the United States. JAMA Dermatol 2021; 157: 824-830.

12. Pokharel A, Koirala IP. Necrobiotic granuloma: an update. Indian J Dermatopathol Diagn Dermatol 2018; 5: 27-33.

13. Erduran F. Evaluation of clinicopathological features and associated conditions in erythema annulare centrifugum: a retrospective observational analysis of 63 patients. Dermatol Pract Concept 2024; 14: e2024039.

14. Chodkiewicz HM, Cohen PR. Paraneoplastic erythema annulare centrifugum eruption: PEACE. Am J Clin Dermatol 2012; 13: 239-246.

15. Bressler GS, Jones RE Jr. Erythema annulare centrifugum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1981; 4: 597-602.

16. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol 2003; 25: 451-462.

17. Fabbri P, Cardinali C, Giomi B, Caproni M. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003; 4: 449-465.

18. Chlebus E, Wolska H, Blaszczyk M, Jablonska S. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus versus systemic lupus erythematosus: diagnostic criteria and therapeutic implications. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 38: 405-412.

19. Lee LA, Gaither KK, Coulter SN, Norris DA, Harley JB. Pattern of cutaneous immunoglobulin G deposition in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is reproduced by infusing purified anti-Ro (SSA) autoantibodies into human skin-grafted mice. J Clin Invest 1989; 83: 1556-1562.

20. Lowe G, Henderson CL, Grau RH, Hansen CB, Sontheimer RD. A systematic review of drug‐induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 2011; 164: 465-472.

21. Renner R, Sticherling M. Incidental cases of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus in association with malignancy. Eur J Dermatol 2008; 18: 700-704.

22. Bangert JL, Freeman RG, Sontheimer RD, Gilliam JN. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus: comparative histopathologic findings. Arch Dermatol 1984; 120: 332-337.

23. Furner BB. Treatment of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Int J Dermatol 1990; 29: 542-547

24. Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2013; 27: 391-404.

25. Reich A, Werth VP, Furukawa F, et al. Treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: current practice variations. Lupus 2016; 25: 964-972.

26. Ezra N, Jorizzo J. Hydroxychloroquine and smoking in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol 2012; 37: 327-334.

27. Lu Q, Long H, Chow S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis, treatment and long-term management of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun 2021; 123: 102707.