Hidradenitis suppurativa: more than a skin disease

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic, inflammatory skin condition that is associated with significant morbidity and reduced quality of life. Early recognition in primary care and proactive management are essential to prevent complications.

- Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic, inflammatory skin disorder that can be misdiagnosed as recurrent infections.

- Early diagnosis and management can prevent complications.

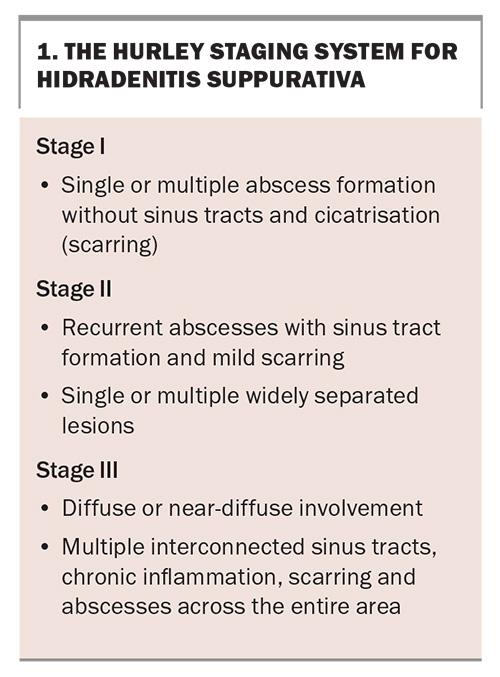

- Appropriate treatment is guided by staging using the Hurley staging system.

- Therapeutic options include topical clindamycin, oral antibiotics and biologic agents, as well as surgical and adjuvant therapies, depending on the stage of disease.

- Weight loss, smoking cessation and mental health support are integral to management.

- Specialist referral should be considered for patients with moderate to severe or refractory disease.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disorder affecting the apocrine gland-bearing areas, often leading to pain, abscess formation, scarring and reduced quality of life. The condition remains underdiagnosed and undertreated, associated with an average diagnostic delay of at least seven years.1 It primarily presents after puberty and affects hair-bearing areas, such as the axillae, groin and inframammary regions, causing the formation of painful nodules, abscesses and sinus tracts.1 The condition significantly impacts patients’ quality of life, often leading to psychological distress.

GPs play a crucial role in the early detection and holistic management of HS. This article provides a practical approach to the identification, diagnosis, staging and management of HS, including lifestyle interventions; medical, surgical and adjuvant therapies; and the indications for specialist referral.

Epidemiology and risk factors

The estimated prevalence of HS in Australia is 0.67%, based on a screening questionnaire. However, only 6.8% of those who screened positive reported a confirmed diagnosis.1 This low diagnosis rate likely reflects under-recognition of HS because of patients not seeking care and fragmented healthcare pathways. HS has a higher prevalence in females and its onset is typically after puberty.1,2

A family history of HS is a key risk factor for its development, with 30% of patients having some genetic predisposition. Obesity is present in about 60% of patients with HS and is strongly linked to disease severity because of increased mechanical friction and inflammation. Smoking is associated with worsened symptoms.1-5 Hormonal influences, such as menstruation, can exacerbate the condition.3,6

Pathophysiology: beyond a skin disease

HS is now recognised as an immune-mediated inflammatory disease, rather than just a follicular occlusion disorder. Dysregulated innate immunity with strong activation of T helper (Th)1 and Th17 pathways, increased tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)-1β , IL-17 and IL-23 pathways, together with an altered microbiome, contribute to chronic inflammation and abscess formation.3,7

Comorbidities

HS is frequently associated with multiple comorbidities, for which screening is recommended. These include acne, metabolic syndrome (affecting about 40% of patients), insulin resistance, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, cardiovascular disease, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), Crohn’s disease, pilonidal sinus disease, depression and spondyloarthritis.3,5,8-10

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

HS is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of all three of the modified Dessau criteria:

- the presence of typical lesions

- in the typical locations

- with chronicity.4,11

Typical lesions are painful nodules, abscesses, sinus tracts and scarring (Figure 1). The typical locations include the axillae, groin, buttocks and inframammary and perianal regions. Chronicity is defined as the occurrence of more than two episodes in six months.4,10

HS typically follows a relapsing-remitting course, with progressive severity. The Hurley staging system helps to classify the disease by stage (Box 1).1

Differential diagnoses for HS include recurrent bacterial abscesses, folliculitis, cutaneous Crohn’s disease and severe acne vulgaris.12

Investigations

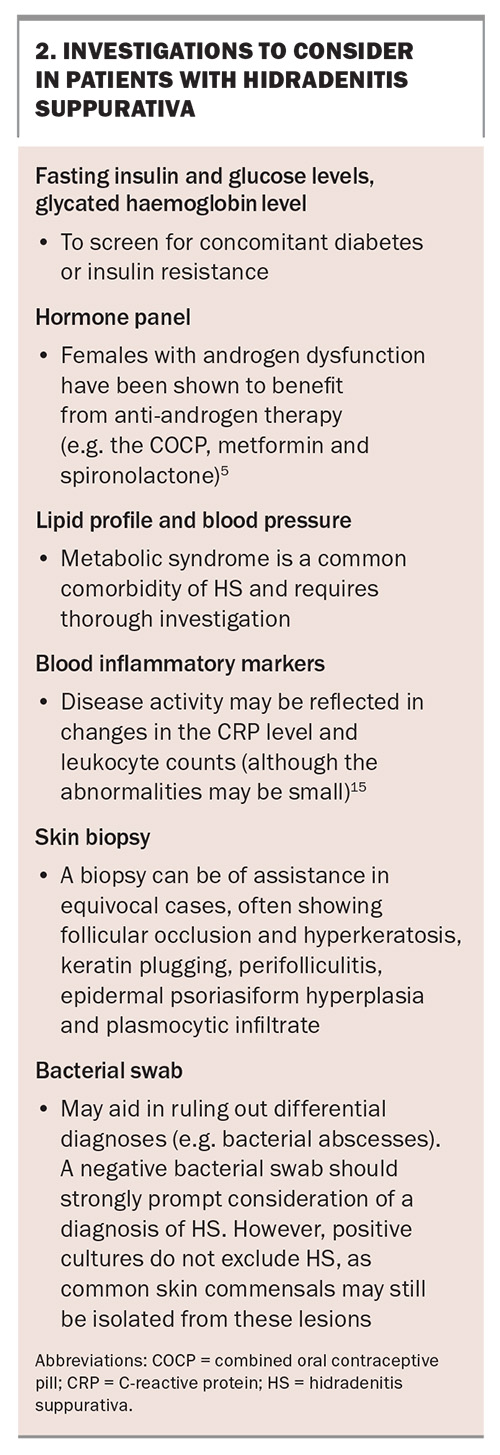

The diagnosis of HS is purely clinical and there is no confirmatory test. However, investigations can support the diagnosis, identify comorbidities and help plan for future treatment (Box 2).13-17

Management

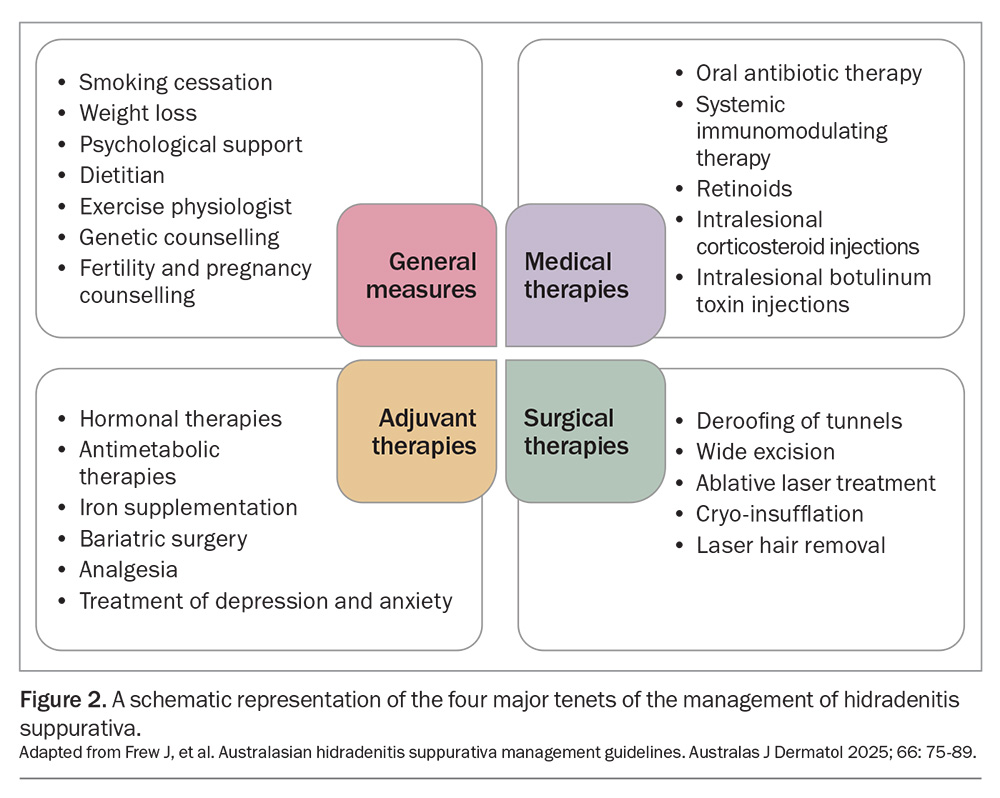

The management of HS is multimodal and tailored to the disease severity. It often incorporates a combination of general measures in addition to medical, surgical and adjuvant therapies. Figure 2 provides a summary of the latest consensus guidelines for the management of HS in Australasia.10 GPs play a vital role in initiating treatment and coordinating care for patients with HS, including its comorbidities.5

General measures

Lifestyle and preventive measures are recommended for all patients with HS, and include smoking cessation, weight loss (when appropriate) and psychosocial support. HS is associated with anxiety, depression and reduced quality of life. One large Australian study showed that about 50% of patients with HS experienced a large or extremely large effect on quality of life from the condition.1 Another study showed that the mean Dermatology Life Quality Index score for HS was higher than for other skin diseases and was correlated with disease severity.18 It is important for clinicians to recognise these psychological impacts and offer support, including consideration of referral to dermatology nurses, support groups (e.g. Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation), specialist psychology services or psychiatry services.5

Medical, surgical and adjuvant therapies

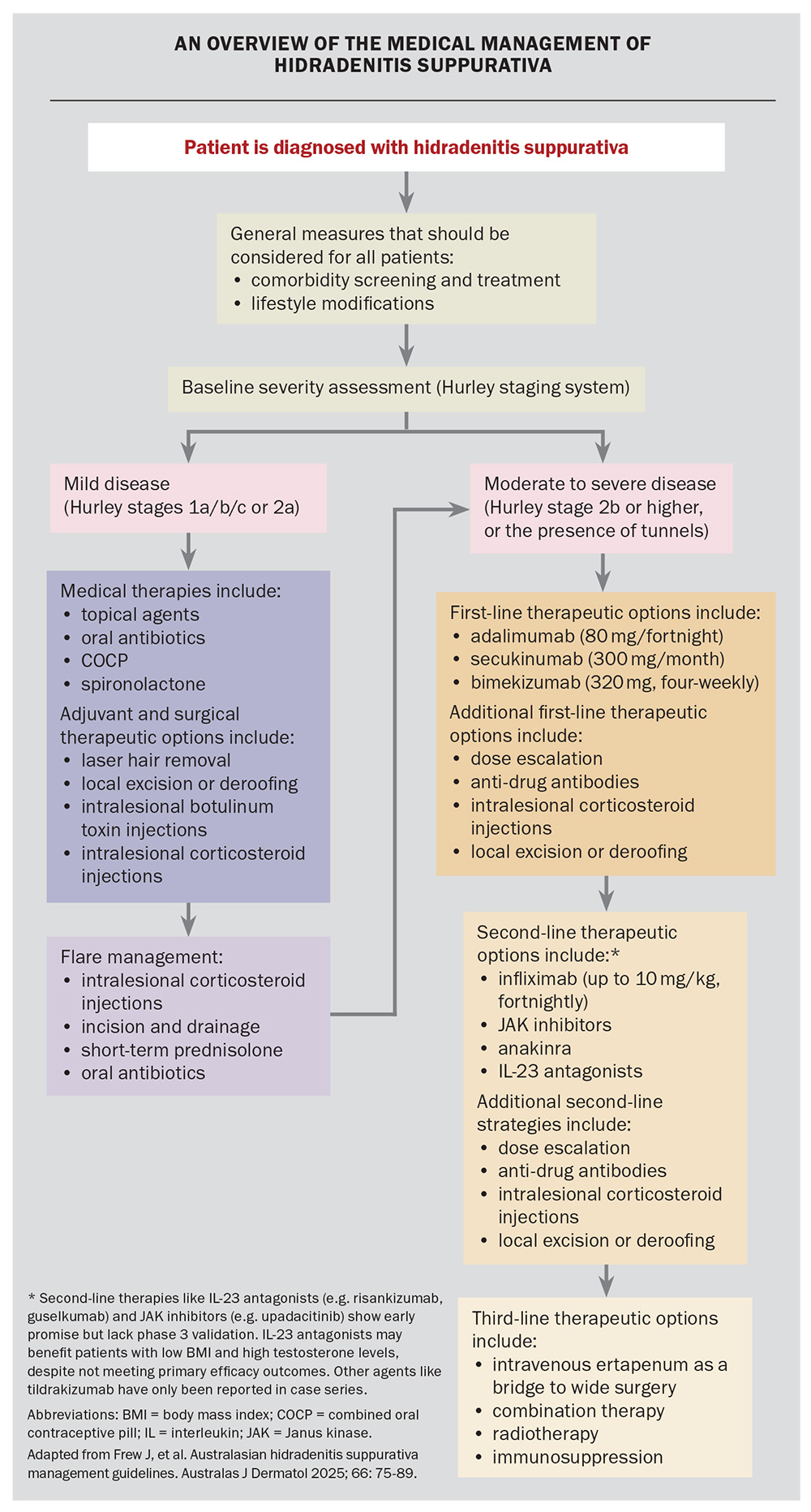

The medical and surgical therapies for HS are summarised in the Flowchart. The therapeutic options depend on the severity of the disease and include the following.

- Mild to moderate disease (Hurley stages 1, 2a and 2b)

– topical antibiotics (e.g. clindamycin 1% gel)

– oral antibiotics (e.g. rifampicin and clindamycin, clindamycin monotherapy, tetracyclines)

– metformin, glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists (especially for adjuvant weight loss or diabetes management)

– oral contraceptives and spironolactone (especially for perimenstrual flaring and patients with comorbid PCOS)

– local surgical intervention (e.g. deroofing)

– intralesional corticosteroid injections5,10 - Moderate to severe disease (Hurley stages 2b, 2c and 3, or any disease with tunnels)

– systemic biological therapy (e.g. adalimumab, secukinumab and bimekizumab)

– surgical intervention: referral for wide excision or deroofing procedures for persistent sinus tracts.10

Acute flares in patients with mild to moderate disease can be treated with courses of antibiotics (e.g. oral tetracyclines), incision and drainage of the lesion, and, for acutely painful lesions, intralesional corticosteroid injections.10

It is important to recognise that the use of serial sequential monotherapy is often disappointing. The most effective method of managing HS is using a combination of therapies (e.g. combining topical antiseptics, oral antibiotics, the combined oral contraceptive pill and local deroofing). The specific combination of therapies should be guided by the patient’s disease status (e.g. deroofing can be helpful for persistently draining tunnels, intralesional corticosteroid injections can be helpful for recurrent painful nodules) and comorbidities (e.g. insulin resistance, PCOS, etc.).

Deroofing

Deroofing (also known as unroofing) is a common procedure for the treatment of HS in which the top of the HS lesion is surgically removed and the wound is left to heal via secondary intention. This allows for the removal of scar tissue and trapped debris with minimal destruction of normal skin.19 It is thought that the removal of the folliculo-pilosebaceous unit also removes the stem cells responsible for the growth of the nodules and sinus tracts. Deroofing has been found to have low recurrence and complication rates.20

A variation of this procedure that can be performed within minutes in an office setting is punch deroofing. This procedure is effective at relieving pain from acute HS flares and is appropriate for use in patients with Hurley stage I HS (those with small lesions). After applying local anaesthetic to the affected area, a 5 to 8 mm punch biopsy tool is used to remove the top of the HS lesion, which is then debrided with a curette and left to heal via secondary intention.19,21

Intralesional corticosteroid injections

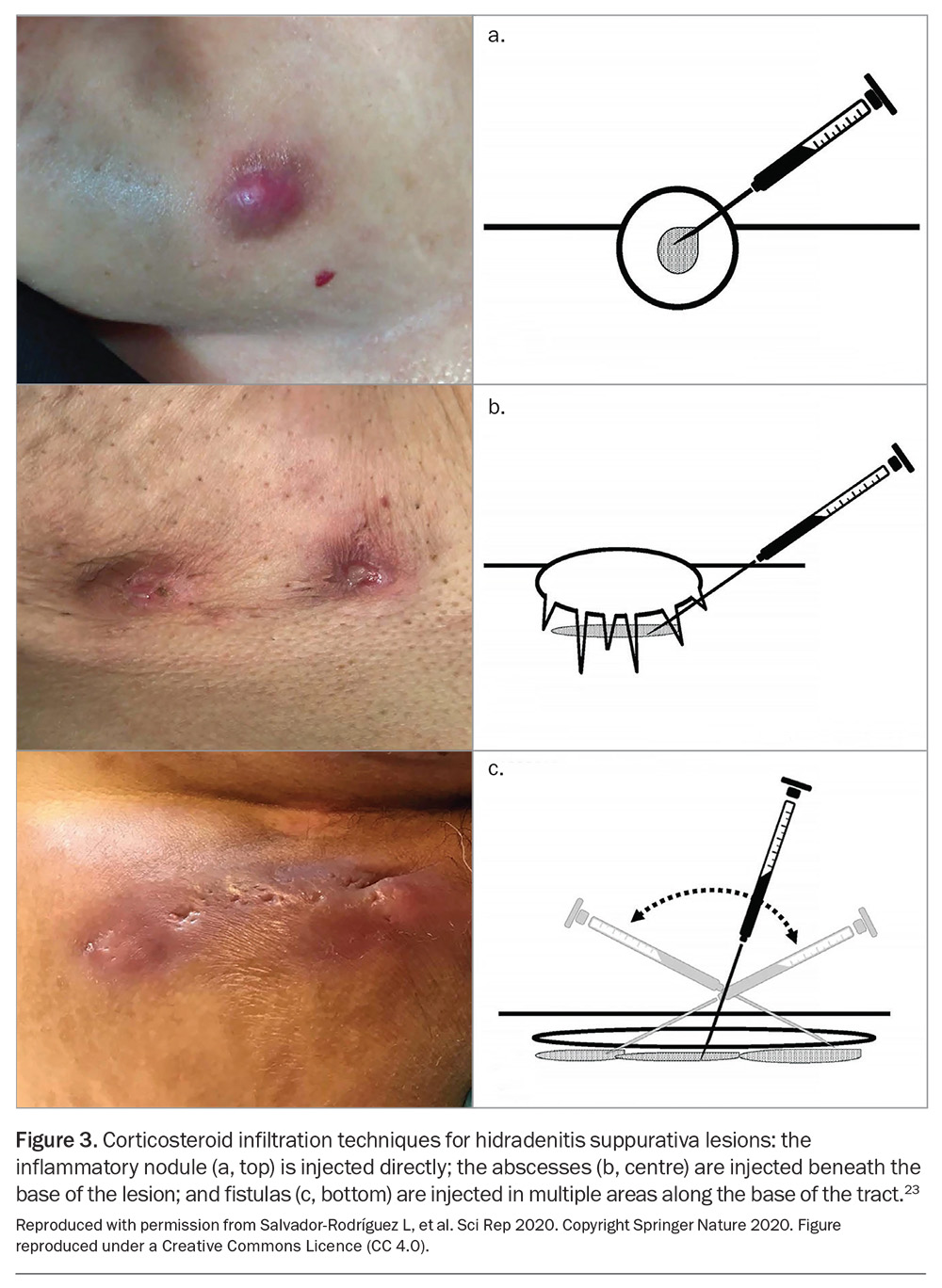

Intralesional corticosteroids (e.g. triamcinolone acetonide) injected into inflamed HS lesions have been shown to reduce pain after one day and inflammation after seven days.22 Figure 3 demonstrates the techniques for corticosteroid infiltration of HS lesions.23 This treatment can be employed every four weeks, using concentrations of 10 mg/mL up to 40 mg/mL, depending on the patient’s disease severity and response to treatment.

Indications for specialist referral

Specialist dermatology services are often required for moderate and severe cases of HS (e.g. those that are refractory despite oral antibiotics), when considering biologic therapies and when there is significant scarring requiring surgical intervention.5

Conclusion

HS is more than a skin condition – it is a chronic and debilitating systemic disease that requires a proactive approach to management. Patient outcomes and quality of life can be improved by the early recognition of HS and implementation of effective treatment strategies. Prompt referral for severe refractory cases ensures timely escalation of care. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Professor Frew has received grants or contracts and consulting fees from Abbvie, Amgen, Azora, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chemocentryx, CSL Behring, Elgia, Fortrea, InflaRx, Janssen, Kirin, Kyowa, LEO Pharma, Medici, Moonlake, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sonoma, Takeda and UCB; and has received payment or honoraria for presentations by Abbvie, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Kirin, Kyowa, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Sonoma and UCB. Dr Sholji: None.

References

1. Calao M, Wilson JL, Spelman L, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) prevalence, demographics and management pathways in Australia: a population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0200683.

2. Sibbald RG, Mufti A. Hidradenitis suppurativa. CMAJ 2015: 187; 1235-1235.

3. Wolk K, Join-Lambert O, Sabat R. Aetiology and pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183: 999-1010.

4. Scala E, Cacciapuoti S, Garzorz-Stark N, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: where we are and where we are going. Cells 2021; 10: 2094.

5. Vekic DA, Cains GD. Hidradenitis suppurativa – management, comorbidities and monitoring. AFP 2017; 46: 584-588.

6. Fernandez JM, Hendricks AJ, Thompson AM, et al. Menses, pregnancy, delivery, and menopause in hidradenitis suppurativa: a patient survey. Int J Womens Dermatol 2020; 10: 368-371.

7. Melchor J, Prajapati S, Pichardo R, Feldman SR. Cytokine-mediated molecular pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: a narrative review. Skin Appendage Disord 2024; 10: 1-8.

8. Dauden E, Lazaro P, Aguilar MD, et al. Recommendations for the management of comorbidity in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 129-144.

9. Garg A, Neuran E, Strunk A. Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with polycystic ovary syndrome: a population-based analysis in the United States. J Invest Dermatol 2018; 138: 1288-1292.

10. Frew J, Smith A, Fernandez Penas P, et al. Australasian hidradenitis suppurativa management guidelines. Australas J Dermatol 2025; 66: 75-89.

11. Moussa A, Willems A, Sinclair RD. Hidradenitis suppurativa: an up-to-date review of clinical features, pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches. Wound Practice and Research 2022; 30: 40-49.

12. Veraldi S, Guanziroli E, Barbareschi M. Differential diagnosis. In: Hidradenitis suppurativa: a diagnostic atlas. 1st ed. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell; 2017. p. 91-100.

13. Ballard K, Shuman VL. Hidradenitis suppurativa. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. PMID: 30521288.

14. Collier EK, Parvataneni RK, Lowes MA, et al. Diagnosis and management of hidradenitis suppurative in women. AJOG 2021; 221: 54-61.

15. Revuz JE, Jemec GBE. Diagnosing hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatologic Clinics 2016; 34: 1-5.

16. Katoulis AC, Koumaki D, Liakou AI, et al. Aerobic and anaerobic bacteriology of hidradenitis suppurative: a study of 22 cases. Skin Appendage Disord 2015; 1: 55-59.

17. DermNet. Hidradenitis suppurativa. DermNet; 2025. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/hidradenitis-suppurativa (accessed May 2025).

18. von der Werth JM, Jemec GB. Morbidity in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol 2001; 144: 809-813.

19. Mansour MR, Rehman RA, Daveluy S. Punch debridement (mini-deroofing): an in-office surgical option for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2024; 90: e193.

20. Kohorst JJ, Baum CL, Otley CC, et al. Surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa: outcomes of 590 consecutive patients. Dermatol Surg 2016; 42: 1030-1040.

21. HS Ireland. Surgical techniques for hidradenitis suppurativa. HS Ireland Hidradenitis Suppurativa Association; 2021. Available online at: https://hsireland.ie/surgical-techniques-for-hs-2-mini-unroofing-and-deroofing/ (accessed May 2025).

22. Riis PT, Boer J, Prens E, et al. Intralesional triamcinolone for flares of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75: 1151-1155.

23. Salvador-Rodríguez L, Arias-Santiago S, Molina-Leyva A. Ultrasound-assisted intralesional corticosteroid infiltrations for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 13363.