Diabetic foot infections

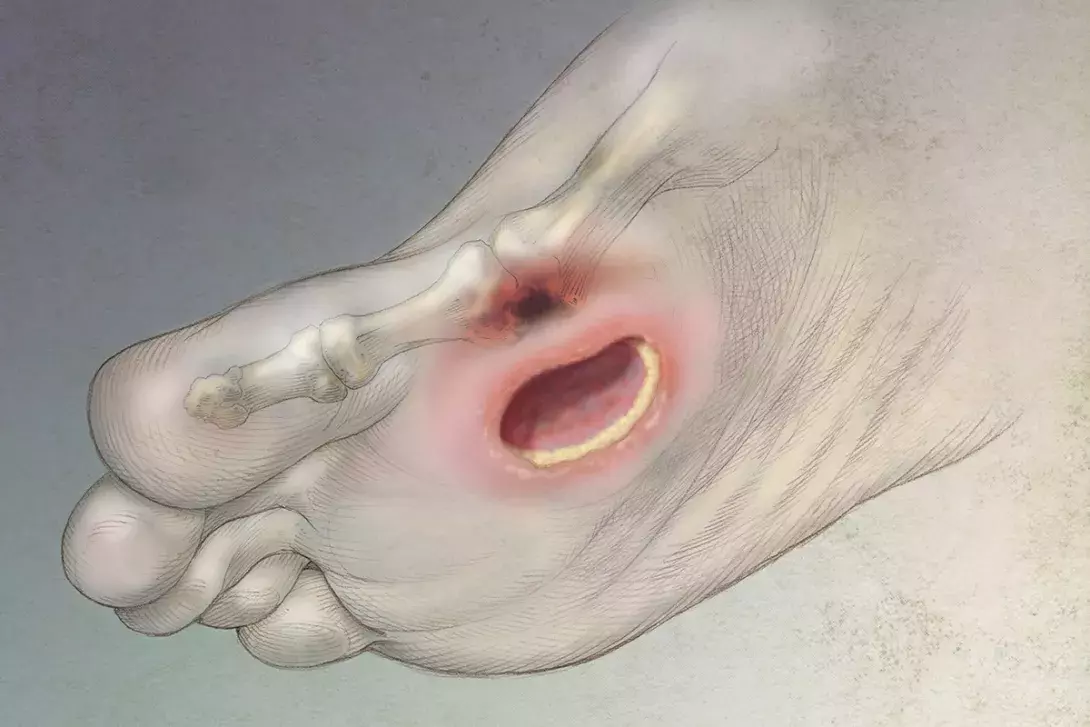

Up to a third of people with diabetes will develop foot wounds and these can become infected and be difficult to manage. An interdisciplinary approach that aims to address the underlying causes can achieve higher rates of wound healing and a reduced time to wound closure, thus reducing the risk of amputation.

It is estimated that up to a third of all individuals with diabetes will develop a wound on their feet during their lifetime.1 This in turn increases the risk of infection, ranging from superficial wound infections to infection of deeper structures, including bone. The main contributing reasons to wound development are:

- peripheral neuropathy

- foot deformities

- foot trauma.

Given the multifactorial pathogenesis, healing of these wounds can be difficult to achieve, and they can often recur. This can be due to peripheral arterial disease and infection. Patients with a diabetic foot wound ideally should be managed by an interdisciplinary team, as this ensures that all risk factors are investigated and managed simultaneously and leads to greater rates of wound closure. The team can include members from the disciplines of endocrinology, podiatry, orthotics, infectious diseases, clinical microbiology, general practice, nursing, radiology and vascular and orthopaedic surgery.2

Differential diagnosis

Clinicians should also consider other diagnoses that can have similar presentations to a diabetic foot wound. These include foot trauma, gout, thrombosis, venous stasis, fracture and acute Charcot neuro-osteoarthropathy.

Wound evaluation

Wound evaluation is based on clinical appearance and supported by investigations. Evaluation should include measuring the dimensions of the wound and determining the causes. The feet should be assessed for loss of protective sensation, and this is best done using a 10 g monofilament.

The adequacy of the vascular supply can be determined by clinical examination of peripheral pulses, the use of arterial doppler ultrasound and measurement of blood pressure in the toe. GPs can feel for the presence of pulses and, if they are absent, request an arterial Doppler ultrasound. A referral to a podiatrist can be considered for assessment of toe pressures. Poor blood supply coupled with poor wound healing should prompt referral to a vascular surgeon.

The wound should be palpated with a sterile probe to determine depth and involvement of structures such as tendons or bone. It should also be examined to evaluate the type of tissue in the wound base. All wounds should be assessed for the presence of infection.

How to determine if infection is present

International recommendations suggest that if two or more of the features listed below are present then infection should be considered:3,4

- local swelling or induration

- erythema extending more than 0.5 cm in any direction from the wound

- local tenderness or pain

- local warmth

- purulent discharge.

If infection is thought to be present, then identifying the causative organism can be helpful in guiding treatment. Antibiotic treatment is only necessary if infection is thought to be clinically present.

Sending superficial swabs for testing from GP clinics should be avoided. A superficial swab of an ulcer may grow organisms that are colonising the area but not causing the infection and may be unhelpful in selecting an appropriate antibiotic. A tissue sample or postdebridement swab is much more likely to provide relevant microbiological guidance (Box).

If infection is present it is important to decide whether this involves soft tissue structures only, or if bone is also involved.

How to detect if osteomyelitis is present

Diagnosis of osteomyelitis is based on clinical examination supported by blood testing and radiological imaging. Osteomyelitis is more likely to be present in chronic wounds that are deep, particularly if there is significant surrounding soft tissue infection. Patients with larger ulcers (more than 2 cm2) or ulcers that have been present for more than four weeks and those with elevated inflammatory markers (e.g. erythrocyte sedimentation rate >70 mm/h) are more likely to have underlying osteomyelitis. Recurrence of ulcers at the same site, visible bone in the wound base, the ability to probe bone with a sterile probe and the presence of an erythematous swollen ‘sausage’ toe also increase suspicion for osteomyelitis.

If a patient has risk factors for osteomyelitis then radiological evaluation with x-ray should be performed. Changes on plain x-ray may include soft tissue swelling, cortical erosion, periosteal reaction, mixed lucency and sclerosis. Radiological changes of osteomyelitis may be delayed, so if suspicion is high then the x-ray may need to be repeated in two weeks or another imaging modality may need to be considered.

Additional testing can then include:

- bone scanning (which can possibly be overly sensitive and show increased uptake of radioactive tracer in a setting of significant overlying soft tissue infection only)

- white cell scanning (which can be falsely positive with soft tissue infection), either alone or in combination with bone scanning

- MRI (which is the most sensitive and specific imaging modality; however, it may be difficult to access in a timely manner and at a reasonable cost)

- bone biopsy (which is the gold standard for diagnosis but is not commonly performed)

- positron emission tomography scanning (which may have a role but is not funded for this indication)

- CT scanning (which has greater sensitivity than plain x-ray to detect osteomyelitis but is not adequate to rule this out and has a limited role in diagnosis).

If a plain x-ray shows osteomyelitis, further imaging is often not necessary. The x-ray can also exclude the presence of a foreign body, which is essential before ordering MRI. If the plain x-ray does not show infection but clinical suspicion is high, then MRI is usually the most useful subsequent test. Bone scans and white cell scans can potentially confuse the diagnosis but can be useful if the x-ray is normal and MRI cannot be accessed or is contraindicated. If imaging suggests osteomyelitis is present, then referral to an interdisciplinary team for management is recommended.2

Treatment

An interdisciplinary team approach has been shown to improve wound healing and reduce amputation rates in patients with a diabetic foot infection.2 GPs are a key member of the interdisciplinary team, assisting with co-ordinating care, potentially assessing and dressing wounds and helping with the prescription of antibiotics.

The key components of achieving successful wound healing are:

- offloading of pressure from the wound

- wound debridement

- wound dressings to create a moist wound environment

- ensuring adequate blood supply to the area

- prescribing antibiotics in the setting of a wound infection.

Control of blood sugar is also important to prevent the progression of other diabetic complications and may assist with wound healing.

Offloading pressure from the wound needs to be tailored to the wound and the individual but may include total contact casts, cast walkers, shoe modifications and felt padding.

Vascular consultation with the aim of performing further vascular investigations, such as lower limb angiography, should be considered if the toe pressure is less than 50 mmHg, foot pulses are absent, there is monophasic or absent wave form on Doppler ultrasound or the wound is not improving over four weeks despite appropriate management.

Wound debridement is an important treatment modality as it removes nonviable and necrotic tissue, allows drainage of purulent fluid, enables the true size of the ulcer to be identified and removes tissue, such as callous, which may increase plantar pressures. It can be performed by an appropriately trained health professional in the ambulatory care setting or in theatre. Debridement should not be undertaken if foot pulses are absent (except emergency drainage of an abscess). If pulses are absent, vascular investigation and management should be promptly arranged.

Dressing selection should aim to encourage moist wound healing and control of exudate. Consideration can be given to the use of dressings containing sucrose octasulfate, which have been shown to be more effective for wound healing than standard dressings in neuroischaemic diabetic foot ulcers.5 We do not recommend topical antibiotics.

Antibiotic choice

Diabetic foot infections that are acute, in patients who have not recently received antibiotics, are usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus or streptococci. If patients have recently received antibiotics, the likelihood of Gram-negative infections increases. Infections that are present for four weeks or more are often polymicrobial, involving Gram-positive and Gram-negative, aerobic and anaerobic bacteria.6,7 Suggested empirical antibiotic choices are shown in the Table.

People who are at high risk of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infection, or who have been previously colonised or infected with MRSA should have antibiotics that will target this organism. Those considered at high risk of MRSA either live in an area with high MRSA rates or have recently spent time in a hospital or nursing home with high rates of MRSA.

People who have been previously colonised or infected with Pseudomonas spp. should have antibiotic therapy that is active against these bacteria. Pseudomonas should also be considered more likely in tropical climates.

Patients started on intravenous antibiotics can be promptly switched to oral medications as they clinically improve; a prescribed length of intravenous therapy is not necessary.

Antibiotics do not need to be continued until the wound completely heals and can be stopped when the clinical signs of infection have resolved. One or two weeks is often an adequate duration of antibiotics when osteomyelitis is not present. If healing is not occurring, the wound should be re-evaluated and the need for further diagnostic studies or alternative treatments should be considered.

Treating osteomyelitis involves longer courses of antibiotics, often including a period of initial intravenous therapy. A total of six weeks of antibiotic therapy can be sufficient, but in more chronic cases, or if several bones are involved, then longer courses may be necessary.

Surgical resection may be necessary for osteomyelitis. If all the infected bone and soft tissue is removed, then only a short course of antibiotics (two to five days) is necessary after resection.

Prevention

After resolution of ulcers, individuals with diabetes remain at a high risk of recurrence and should have ongoing monitoring. Patients should be educated about the importance of wearing appropriate footwear at all times, even indoors, and checking their feet daily for early signs of skin damage or breakdown. Good foot hygiene should be emphasised along with the importance of promptly addressing even very minor wounds. Family members should also be made aware of the need for patients to always wear appropriate footwear.

Conclusion

Good outcomes can be achieved for patients with diabetic foot infections. This requires a comprehensive approach and a focus on controlling the factors that led to the initial wound infection. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.