Type 2 diabetes in young adults: a management guide for GPs

Young adults with type 2 diabetes are at higher risk of early complications and mortality and require a nuanced approach to management. Clinicians can be guided by recommendations from the Australian consensus statement on the management of type 2 diabetes in young adults.

Note

This is an online update of the original version of this article that was published in the September 2022 issue of Medicine Today. This update was prepared for National Diabetes Week 2024.

- Type 2 diabetes, most commonly a condition of older age, is becoming increasingly prevalent in the young adult age group.

- Type 2 diabetes in young adults has a more aggressive course with a greater risk of complications and early mortality.

- The Australian consensus statement on the management of type 2 diabetes in young adults considers issues for young adults and highlights areas where management might differ from that of older adults. Special considerations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians are highlighted.

- GPs play an important role in identifying type 2 diabetes in young adults and are encouraged to facilitate access to endocrinologists and specialised multidisciplinary available.

- GPs are pivotal in providing support and education, particularly with respect to pregnancy, contraception and psychological health, and in providing continuity of care, especially during transition periods.

- All clinicians involved in diabetes care are encouraged to review the main published summary recommendations for comprehensive guidance.

It is now well accepted that type 2 diabetes in young adults is a more aggressive condition than type 2 diabetes that develops in older age, with a high risk for early complications and early mortality. On a background of high rates of being overweight and having obesity in the early years, young adults with type 2 diabetes are a growing demographic. For young adults with type 2 diabetes, there is an increased lifetime risk of diabetes complications and a mortality risk that appears worse than that seen in people with type 1 diabetes when matched for age of diagnosis and duration.1 In this context, the first Australian consensus statement on the management of type 2 diabetes in young adults, Management of type 2 diabetes in young adults aged 18-30 years: Australian Diabetes Society (ADS)/Australian Diabetes Educator Association (ADEA)/Australasian Paediatric Endocrinology Group (APEG) consensus statement, published in the Medical Journal of Australia, ‘considers areas where existing type 2 diabetes guidance, directed mainly towards older adults, may not be appropriate or relevant for the young adult population’.2 Recommendations are provided on many aspects of care; these are aligned with the current management guidelines for type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents.3 Importantly, dedicated considerations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians are highlighted. In this article, we provide an overview of the main management recommendations from a GP’s perspective, with a particular emphasis on the important role of the GP, who remains at the forefront of screening, diagnosis and team care co-ordination.

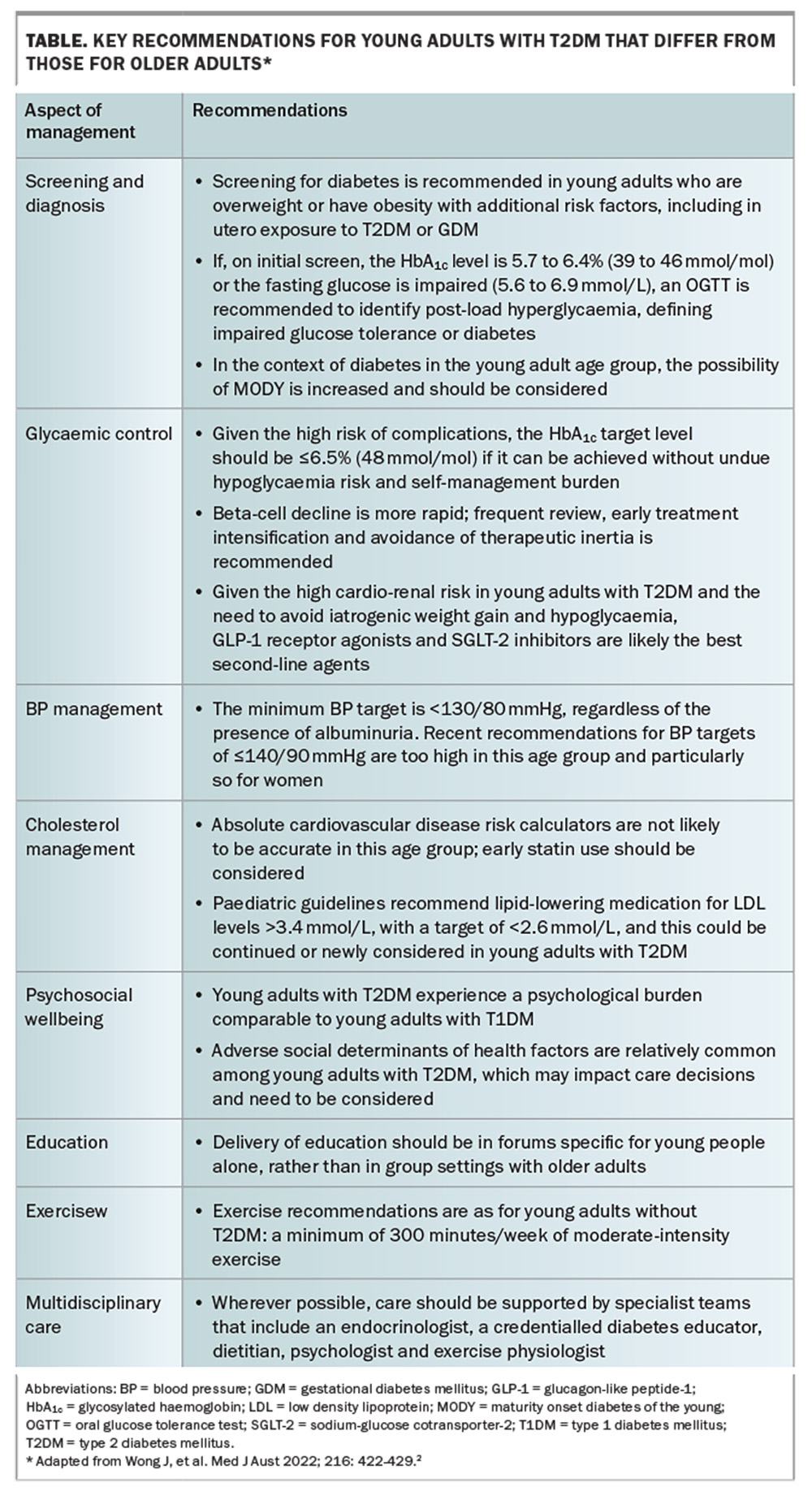

Specialist multidisciplinary care of young adults with type 2 diabetes is recommended where possible, and primary care is well placed to provide continuity of supportive care in the context of family and community. This is important as type 2 diabetes in young adults is a chronic disease requiring lifelong management, often occurring at life-stages characterised by social and economic transition. All clinicians involved in diabetes care are encouraged to review the main published summary recommendations for comprehensive guidance (https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/216/8/management-type-2-diabetes-young-adults-aged-18-30-years-adsadeaapeg-consensus).2 A summary of the key recommendations that differ from those for older onset type 2 diabetes are provided in the Table.

Screening for type 2 diabetes in young adults

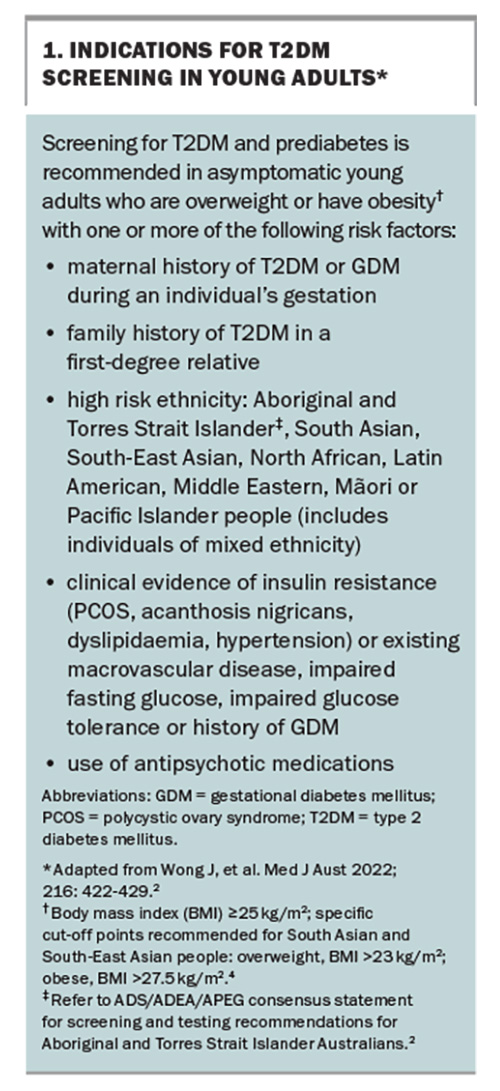

Type 2 diabetes can and does occur in young adults; the main challenges are to raise awareness and diagnose it. The commonly used Australian Type 2 Diabetes Risk Assessment Tool (AUSDRISK) may be less accurate in young adults. In its place, a new risk-based screening approach is suggested. GPs are encouraged to consider the possibility of type 2 diabetes in a young person who is overweight or has obesity (as these are strong risk factors for young adults with type 2 diabetes), in the presence of one other risk factor, such as prior gestational diabetes mellitus, in utero exposure to hyperglycaemia, or an ethnicity/race at high risk for type 2 diabetes overall (Box 1). In recognition of the very high risk of young adult type 2 diabetes in Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people, case-finding recommendations differ and screening can be recommended even in the absence of other risk factors.2

The criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes remain the same as for older adults. If initial tests are within the normal range, screening should continue at a minimum of three-yearly intervals; however, screening is recommended to be repeated earlier if the patient’s body mass index is increasing. Further testing is required when initial results are near the borderline for the diagnosis for diabetes; if the patient’s fasting blood glucose level is in the impaired fasting range (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L) or if the glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level is 5.7 to 6.4% (39 to 46 mmol/mol), an oral glucose tolerance test is recommended to identify diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance, defined by a post-load hyperglycaemia blood glucose level of 7.8 to 11.0 mmol/L. This is particularly important in Asian populations, where post-load glucose abnormalities are the common pattern. If the results of these initial tests are in the impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance range, and diabetes is not diagnosed by an oral glucose tolerance test, screening should be repeated annually (in addition to optimising lifestyle factors). If completely normal, repeat assessments can be done every three years (though this should be re-evaluated if the risk profile changes).

Is it type 2 diabetes or type 1 diabetes or another type?

Clinically, the specific diabetes type in young adults can be sometimes challenging to determine given the overlapping features of type 2 and type 1 diabetes. For example, type 1 diabetes can present in patients who are overweight or have obesity and young adults with type 2 diabetes can present with initial ketoacidosis (although they may subsequently be managed without insulin). It is recommended that autoantibody testing for islet cell antibodies (we suggest glutamic acid decarboxylase and insulinoma antigen-2 antibodies as a minimum) be considered in young adults presenting with diabetes to exclude an autoimmune aetiology, such as slowly progressive type 1 diabetes.

A high index of suspicion should also be present for the possibility of rarer forms of diabetes, such as monogenic diabetes, masquerading as young adults with type 2 diabetes. Taking a family history is particularly important and an initial clue to monogenic diabetes or maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is the presence of multigenerational family members with early onset diabetes (diagnosed as either type 2 or type 1) along one family line, in an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Consideration of monogenic diabetes should also be prompted if the patient is not overweight and there are no signs of insulin resistance typical for type 2 diabetes (such as acanthosis nigricans, elevated waist circumference, signs of polycystic ovary syndrome). Although relatively rare (reported in less than 3% of young adults presenting with type 2 diabetes), the treatment and prognosis are different and there are potential implications for the wider family. Specialist referral should be considered if the diabetes type is in doubt.

Lifestyle recommendations

GPs are well placed to assess and support a family-centred approach to lifestyle modification to assist weight and glucose management. Referral to an accredited practicing dietitian is recommended, as no single dietary approach is specified. An important first step is reducing energy- dense, nutrient-poor foods, including the elimination of calorie-dense or sugar-sweetened beverages, such as fruit-based drinks. Individualised strategies that target improving food literacy should be provided, including an emphasis on reducing reliance on processed and takeaway foods, seemingly common in this age group. From our experience, clinicians should be alert to the possibility of disordered eating, food insecurity and poor health literacy in young adults with type 2 diabetes.

Among older adults in the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT), a primary care-based weight management program incorporating a low energy formula diet achieved remission of diabetes in almost half of the patients randomised to this intervention.5 These results were supported by a similar, although nonrandomised, Australian trial.6 Although young adults with type 2 diabetes were not well represented in this trial, the ADS/ADEA/APEG consensus statement notes that this approach does merit further consideration given the potential benefits of inducing remission in this age group. Further research is needed to identify the most effective nutritional approach for young adults with type 2 diabetes.

Physical activity is encouraged, as for healthy young populations, and sedentary behaviour should be reviewed where possible with recommendations to limit recreational screen time to less than two hours per day. Clinicians should ascertain sleep routines and encourage sleep hygiene practices, such as consistent routines and reduction of evening electronic device use, which may help to assist sleep quality and duration. The specific impact of these recommendations on metabolic control is not yet clear but they are likely to be of benefit. There is evidence for relative resistance to exercise interventions in young adults with type 2 diabetes, which may have a physiological basis, and so any failure to improve should not be considered a failure of personal action.7 Equally, it should not be a reason to discount the benefits of physical activity as part of overall management.

Psychosocial health in young adults with type 2 diabetes

As a group, young adults with type 2 diabetes experience a relatively high burden of emotional health problems, which may not be evident initially. Assessment of a patient’s psychological health, in particular screening for the co-occurrence of symptoms of depression, anxiety or diabetes distress, should be considered at every visit. Screening tools, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire, can be used to identify patients in need of further support and intervention.2 Given the bidirectional impact of psychological conditions, the use of antipsychotic medications in young adults who are overweight or have obesity should also trigger screening for the presence of type 2 diabetes. Early referral to age-appropriate mental health services is encouraged.

Glycaemic control

For young adults with type 2 diabetes, the lifetime risk for diabetes complications is high, in part driven by a long exposure to hyperglycaemia in the absence of a cure. Thus, the current recommendations are for stringent glycaemic management at an early age. The recommended glycaemic target for young adults is now specified: the HbA1c target level should be 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) or less, if it can be achieved without undue hypoglycaemia risk and self-management burden. This target is lower than those set for youth with type 1 diabetes, given the lower propensity for hypoglycaemia in young adults with type 2 diabetes.

Beta-cell functional changes and decline may be more rapid, and metformin monotherapy failure rates may be higher than usually seen. The main clinical implications of these findings are that therapeutic inertia should be avoided, and regular three-monthly follow up and early intensification beyond metformin monotherapy is likely to be needed. Referral to specialist teams would be appropriate at this stage or earlier.

For the treatment of young adults with type 2 diabetes, metformin remains first-line, but the early use of newer agents (glucagon-like peptide-1 [GLP-1] receptor agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 [SGLT-2] inhibitors and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors) is recommended given the lower propensity for hypoglycaemia and weight gain, both particularly important to avoid in young adults.

Given the high cardio-renal risk in young adults with type 2 diabetes, GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors are the likely best second-line agents in accordance with the Australian Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for Diabetes.8 All of these agents are approved for use in Australia in people with type 2 diabetes who are over the age of 18 years. However, in the context of the risk of SGLT-2 inhibitor-induced ketoacidosis, caution is recommended when using this class of medication in young adults with type 2 diabetes who have ever presented with ketoacidosis. If these agents are used, a discussion of the risks and the use of effective contraception in women is essential because there is limited safety evidence for the use of these newer agents in pregnancy.

Diabetes complications

Despite a short preclinical stage for young adults with type 2 diabetes, it is apparent that complications can be present early on, or even at the time of diagnosis, and can progress more rapidly than what is seen in older people with type 2 diabetes. Thus, despite their young age, screening for retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy should begin at diagnosis of young adults with type 2 diabetes (unlike type 1 diabetes) and repeated in a timely fashion according to clinical findings. GPs play an essential role in facilitating and supporting this care.

Overt or clinically significant macrovascular disease is not prevalent in young adults with type 2 diabetes; however, the early presence of adverse cardiovascular disease risk factors is common. Absolute cardiovascular disease risk calculators are unlikely to be accurate in this age group and early statin use should be considered.

Early intervention for elevated blood pressure is encouraged. The recommended minimum target blood pressure is less than 130/80 mmHg, compared with the blood pressure targets in older adults of less than 140/90 mmHg. ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers remain first-line therapeutic options for hypertension, especially in the context of an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio; however, the potential teratogenic effects of these agents and statins should be discussed together with advice on effective contraception. Early referral to a nephrology specialist is recommended if there is concern regarding aetiology, or in the context of worsening albuminuria or declining estimated glomerular filtration rate levels on repeat assessment. Additionally, assessment for nonclassic complications and comorbidities, such as the presence of nonalcoholic metabolic-associated fatty liver disease, polycystic ovary syndrome and obstructive sleep apnoea, are encouraged.

Pregnancy and preconception care

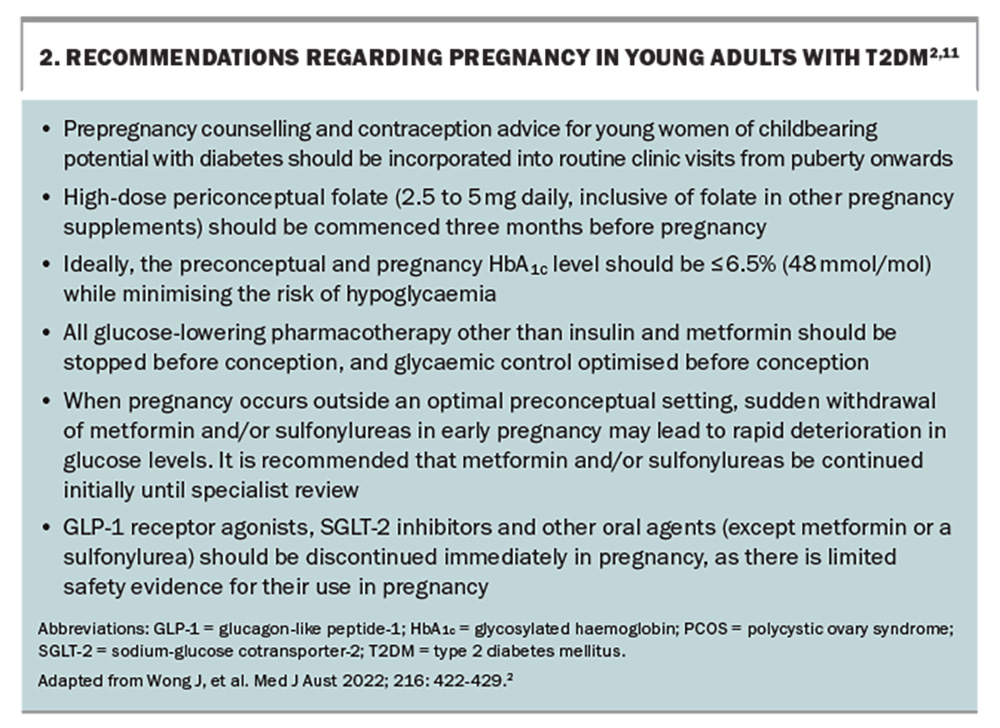

There are higher rates of congenital abnormalities, pre-eclampsia, preterm birth, large for gestational age babies and other adverse outcomes in pregnancies affected by type 2 diabetes.9 Optimal preconception and antenatal glucose levels, and avoidance of excessive gestational weight gain may reduce some of these risks. Exposure to hyperglycaemia in utero seems to amplify the risk for early diabetes in offspring. Prepregnancy planning, including engagement with specialist team support and optimising preconception weight and glucose levels with a preconception HbA1c target level of 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) or less, should be strongly encouraged.

The long half-life of once weekly GLP-1 agonists needs to be reviewed in pregnancy planning to allow adequate time for drug elimination. In the event of an unplanned pregnancy, the newer glucose-lowering agents should be immediately discontinued because of the potential adverse effects. It is recommended that metformin and sulfonylureas not be immediately discontinued in early pregnancy until specialist review, to avoid loss of glucose control at the time of organogenesis.

Practical recommendations for pregnancy planning are outlined in Box 2. Please also see the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners guideline Type 2 diabetes, reproductive health and pregnancy for a summary of safety and risks of common diabetes medications in pregnancy, including ACE inhibitors and statins.10

Breastfeeding is particularly encouraged, given evidence that it may offer protection against the development of early onset type 2 diabetes in offspring, but again noting that only insulin or metformin are compatible with breastfeeding.11 Clinicians are also encouraged to take a proactive approach to effective contraception. Long-acting reversible contraceptives, for example hormonal and nonhormonal intrauterine contraceptive devices and subcutaneous progestogen implants, have been recommended as first-line contraceptive options for adolescents and young women with diabetes.

Education and the optimal model of care

Specific structured person-focused education for young adults is necessary and different to that which is available for older patients with type 2 diabetes or young patients with type 1 diabetes. Education, ideally provided with the expertise of a credentialled diabetes educator experienced with youth, should acknowledge the impact on family, any individual learning needs, and should be integrated into every clinical consultation. Suggested practical topics to address for young adults include the impact of the diabetes diagnosis on education, occupational choice and navigating the health system. GPs should initiate a multidisciplinary healthcare team plan that provides for this support.

Management of type 2 diabetes has always been in the domain of primary care. The optimal model of care for young adults with type 2 diabetes is not yet clear; however, given the high risk, and often suboptimal response to treatment and complex comorbidity, it is recommended that, in addition to management by the GP, young adults with type 2 diabetes should be referred to multidisciplinary specialist clinics with access to endocrinologists, credentialled diabetes educators and specialist psychological, dietary and bariatric support. This does not preclude or diminish the important role of primary care. GPs are pivotal in providing support and education (particularly with respect to pregnancy, contraception and psychological health), facilitating access to multidisciplinary care and providing continuity of care (especially during transition periods), which are all essential to improving outcomes for young adults living with type 2 diabetes.

Conclusion

Type 2 diabetes is no longer just seen in older people, but increasingly in young adults, where the disease appears to be more aggressive. GPs play an important role in identifying type 2 diabetes in young adults, and in supporting timely access to specialist services. Screening for diabetes should be arranged for patients who are overweight or have obesity in the presence of another risk factor and especially for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

The ADS/ADEA/APEG consensus statement provides guidance to GPs and other healthcare providers on many aspects of diabetes care for this growing demographic, which differs from that for older-onset type 2 diabetes. GPs involved in the care of young adults with type 2 diabetes are encouraged to review these recommendations with the shared aim to improve the lives of young adults living with diabetes. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Professor Wong, Dr Wu and Dr Deed: None relevant to the content of this article.

References

1. Constantino MI, Molyneaux L, Limacher-Gisler F, et al. Long-term complications and mortality in young-onset diabetes: type 2 diabetes is more hazardous and lethal than type 1 diabetes. Diabetes care 2013; 36: 3863-3869.

2. Wong J, Ross GP, Zoungas S, et al. Management of type 2 diabetes in young adults aged 18–30 years: ADS/ADEA/APEG consensus statement. Med J Aust 2022; 216: 422-429. Available online at: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/216/8/management-type-2-diabetes-young-adults-aged-18-30-years-adsadeaapeg-consensus (accessed July 2024).

3. Peña AS, Curran JA, Fuery M, et al. Screening, assessment and management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents: Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group guidelines. Med J Aust 2020; 213: 30-43.

4. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004; 363: 157-163.

5. Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2018; 391: 541-551.

6. Hocking SL, Markovic TP, Lee CM. Intensive Lifestyle intervention for remission of early type 2 diabetes in primary care in Australia: DiRECT-Aus. Diabetes Care 2024; 47: 66-70.

7. Burns N, Finucane FM, Hatunic M, et al. Early-onset type 2 diabetes in obese white subjects is characterised by a marked defect in beta cell insulin secretion, severe insulin resistance and a lack of response to aerobic exercise training. Diabetologia 2007; 50: 1500-1508.

8. Living Evidence for Diabetes Consortium. Australian evidence-based clinical guidelines for diabetes. Living Evidence for Diabetes Consortium, Sydney. Available online at: https://www.diabetessociety.com.au/living-evidence-guidelines-in-diabetes/ (accessed July 2024).

9. TODAY Study Group. Pregnancy outcomes in young women with youth-onset type 2 diabetes followed in the TODAY Study. Diabetes Care 2022; 45: 1038-1045.

10. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Type 2 diabetes, reproductive health and pregnancy: safety and risks of common diabetes medicines in pregnancy. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Canberra. Available online at: https://www.racgp.org.au/getattachment/19a48b1e-097b-4896-9bdf-b3d01be3cd0d/attachment.aspx?disposition=inline (accessedJuly 2024).

11. Rudland VL, Price SAL, Hughes R, et al. ADIPS 2020 guideline for pre-existing diabetes and pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2020; 60: E18-E52.