What’s the diagnosis?

Reticulated hyperpigmentation and erythema on the legs

Case presentation

A 47-year-old woman presents with a four-week history of a reticulated (‘lace-like’) eruption on her lower legs (Figure 1). It was initially intermittent but has become fixed.

On examination, there are non-blanching reticulated patches with hyperpigmentation and erythema observed on the anteromedial aspect of the right shin and anterolateral aspect of the left shin. There is no tenderness on palpation.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Livedo reticularis

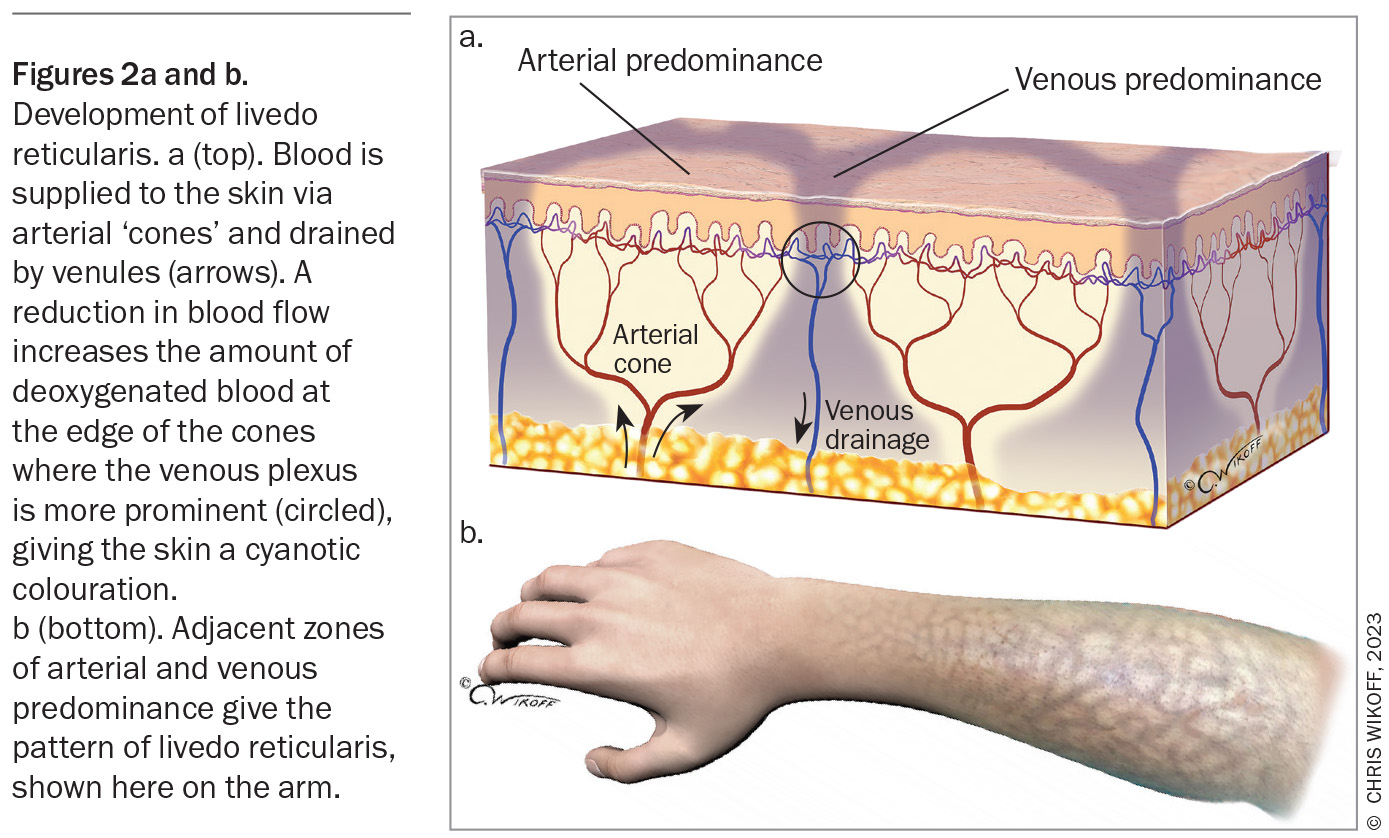

Livedo reticularis refers to the physical finding of reticulated, mottled, cyanotic discolouration of the skin. The pattern arises due to disruptions in blood flow through the skin vasculature (Figure 2).1

There are three main categories of livedo reticularis and many causes.

-

Physiological livedo reticularis (cutis marmorata) is a response to exposure to cold that resolves upon rewarming. It is common in healthy babies and is also seen in many children and adults.

-

Primary livedo reticularis may be congenital or acquired. The congenital condition, which is also known as cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita, is discussed further below. The acquired (idiopathic) condition primarily affects adults and is a diagnosis of exclusion.

-

Secondary livedo reticularis is associated with underlying conditions that lead to blood flow impairment. These include coagulopathy, thrombo-occlusive diseases, arteriosclerosis, arteritis, congestive cardiac failure, infections and paralysis.2,3

Livedo reticularis is not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. Her skin eruption was not triggered by exposure to cold and she did not have comorbidities causing blood flow impairment. In addition, the eruption was hyperpigmented and not cyanotic or violaceous.

Livedo vasculitis

Livedo vasculitis is a rare chronic vasculopathy with an estimated incidence of 1:100,000.4 The condition predominantly affects middle-aged adults, mainly women (the ratio of affected females to males is 2.4-3 to 1).5

The exact pathogenesis of livedo vasculitis is unclear but it has been associated with the presence of various prothrombic factors, such as factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin mutations, antiphospholipid antibodies and sticky platelet syndrome as well as deficiencies in protein C, protein S and antithrombin III.6-8 It is thought that increased coagulation and impaired fibrinolysis lead to thrombi and blood vessel occlusion, resulting in ischaemia and subsequent pain.9

Livedo vasculitis typically starts as erythematous or purpuric macules or papules that are extremely painful and occasionally pruritic. The lesions are usually bilateral and most commonly affect the lower legs, ankles and dorsum of the feet.10 Over time, the lesions turn into punched-out ulcers that heal slowly (over three to four months), forming residual stellate, ivory-white, atrophic scars with peripheral telangiectasias and haemosiderin pigmentation (atrophie blanche).4 The hallmark of livedo vasculitis is the recurring cycle of ulcer formation and healing.

Although the case patient is female and within the age group most commonly affected by livedo vasculitis, this is not the correct diagnosis. Her cutaneous eruption was painless and she did not have a characteristic ulcer.

Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita

Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (CMTC) is a rare vascular malformation of capillaries characterised by livedo reticularis. The condition has been associated with two congenital abnormalities: Adams-Oliver syndrome and phakomatosis pigmentovascularis.11,12 The exact aetiology of CMTC is unknown, but has been linked with ARL6IP6 and GNA11 gene mutations.13-15 Patients often do not have a family history of the condition. Postzygotic GNA11 gene mutation may explain the low occurrence of familial cases.

CMTC is usually asymmetrical, with the limbs being most commonly affected.16 In most patients, the lesions slowly fade over the first few years of life.16 The condition should not be confused with physiological livedo reticularis (discussed above). CMTC can be enhanced by exposure to cold but lesions do not disappear on rewarming.

CMTC is not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, whose skin eruption had not been present since birth.

Erythema ab igne

This is the correct diagnosis. The term directly translates to redness (erythema) from (ab) fire (igne). It is an acquired, erythematous and pigmented dermatosis with a reticulated appearance that results from repeated or prolonged exposure to infrared radiation. The eruption is usually transient and initially erythematous but becomes persistent and hyperpigmented with repeated exposure. Over time, the skin can become atrophic and hyperkeratotic. Some patients may develop pruritus and a burning sensation. The case patient’s history supports the diagnosis: when asked about daily activities, she mentions that during the past six months she has been sitting close to an electric heater for up to three hours every night while watching television.

Prior to the invention of central heating, the classic presentation of erythema ab igne was reticulated pigmentation on the lower limbs following recurrent periods of prolonged sitting in front of a fireplace or electric heater.1,17,18 The distribution may be symmetrical or asymmetrical, depending on an individual’s habitual sitting style. For those who prefer to sit to the side of the heat source, the eruption usually affects the inner aspect of one leg and the outer aspect of the other leg, as portrayed in the presented case. For those who prefer to sit directly in front, the eruption usually affects both legs symmetrically. Other common heat sources that can cause erythema ab igne include hot water bottles and personal heat pads, car heaters and heated car seats.19 Heat generated by laptop computers can affect the anterior thighs.20 Occupational exposures may be relevant – for example, bakers who are routinely exposed to hot ovens may develop the dermatosis on the arms whereas jewellers who are exposed to heat sources may develop it on the face.

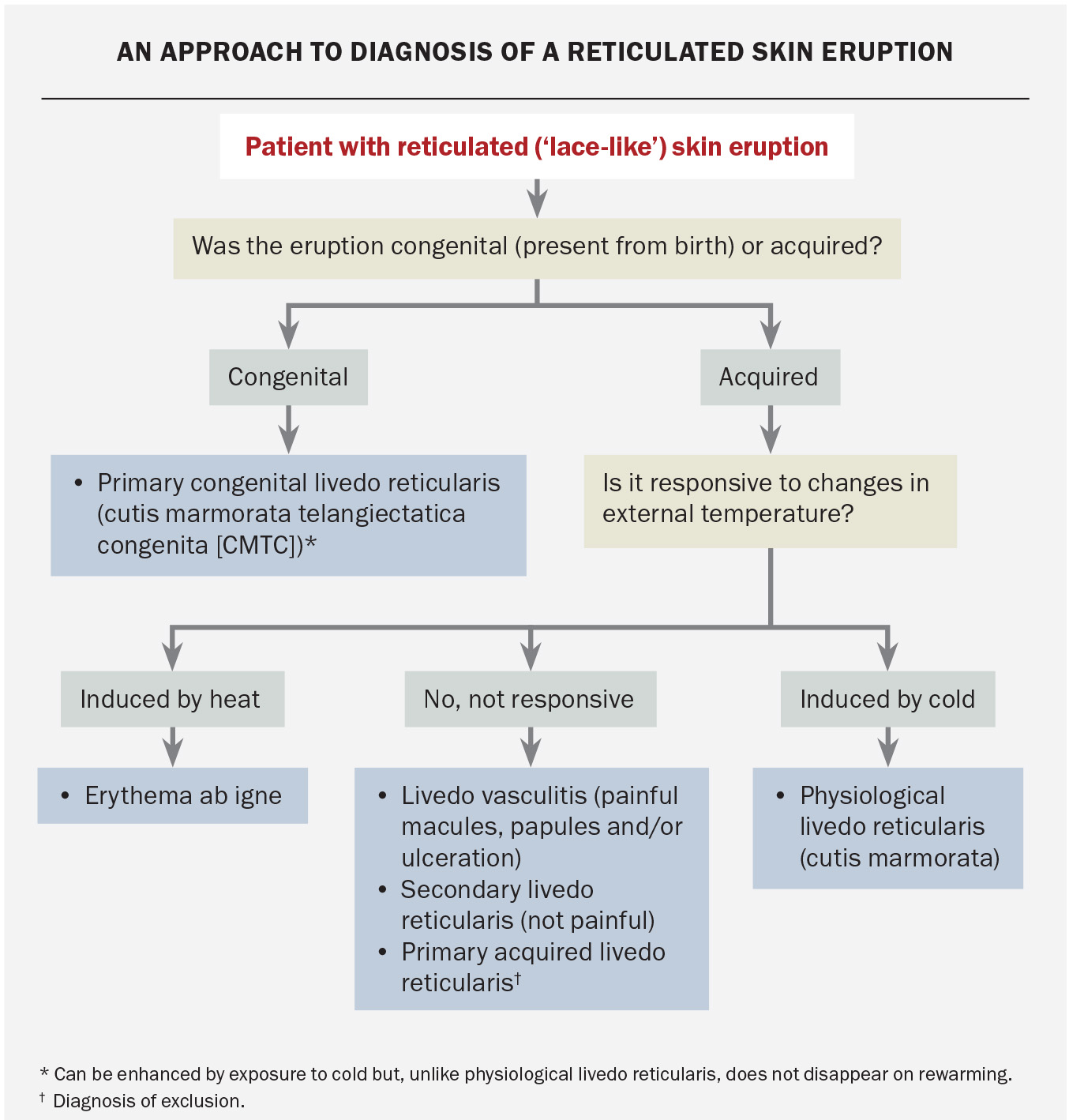

An approach to the diagnosis of reticulated skin eruptions is outlined in the Flowchart.

Management

The main principal of management of erythema ab igne is removal of the heat source. The possibility of an underlying condition that may be leading the patient to prolonged use of heat sources should also be considered, such as impaired thermoregulation caused by hypothyroidism or chronic pain caused by chronic pancreatitis or malignancies.21,22 Investigations for underlying conditions should be performed where indicated.

In milder cases, the erythema self-resolves within a few months. However, pigmentation and atrophy, once developed, may persist for many years and may never resolve. In severe cases, there is an increased risk of skin malignancy as a result of repeated heat injuries – actinic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma and Merkel cell carcinomas have been reported.23-29 Given the increased risk of skin cancers, regular full skin examinations should be considered in patients who have permanent skin hyperpigmentation.

Outcome

The diagnosis was explained to the case patient and she was advised to stop sitting close to her electric heater. The erythema improved, but the increased pigmentation remained. This may fade over time but is usually permanent. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr Isobel Pye for her contributions to this article.

References

1. Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L (eds). Disorders due to physical agents [Section 13]. In: Dermatology, 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018.

2. Pennington M, Yeager J, Skelton H, Smith KJ. Cholesterol embolization syndrome: cutaneous histopathological features and the variable onset of symptoms in patients with different risk factors. Br J Dermatol 2002; 146: 511-517.

3. Singh AK, Wetherley-Mein G. Microvascular occlusive lesions in primary thrombocythaemia. Br J Haematol 1977; 36: 553-564.

4. Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Davis MDP. Update of management of connective tissue diseases: livedoid vasculopathy. Dermatol Ther 2012; 25: 183-194.

5. Di Giacomo T, Hussein T, Souza D, Criado PR. Frequency of thrombophilia determinant factors in patients with livedoid vasculopathy and treatment with anticoagulant drugs – a prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24: 1340-1346.

6. Criado PR, Rivitti EA, Sotto MN, de Carvalho JF. Livedoid vasculopathy as a coagulation disorder. Autoimmun Rev 2011; 10: 353-360.

7. Castillo-Martínez C, Moncada B, Valdés-Rodríguez R, González FJ. Livedoid vasculopathy (LV) associated with sticky platelets syndrome type 3 (SPS type 3) and enhanced activity of plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1) anomalies. Int J Dermatol 2014; 53: 1495-1497.

8. Criado PR, Di Giacomo TH, Souza DP, Santos DV, Aoki V. Direct immunofluorescence findings and thrombophilic factors in livedoid vasculopathy: how do they correlate? Clin Exp Dermatol 2014; 39: 66-68.

9. Alavi A, Hafner J, Dutz JP, et al. Livedoid vasculopathy: an in-depth analysis using a modified Delphi approach. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 69: 1033-1042e1.

10. Hairston BR, Davis MDP, Pittelkow MR, Ahmed I. Livedoid vasculopathy. Arch Dermatol 2006; 142: 1413-1418.

11. Fayol L, Garcia P, Denis D, Philip N, Simeoni U. Adams-Oliver syndrome associated with cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and congenital cataract: a case report. Am J Perinatol 2006; 23: 197-200.

12. Chang BP, Hsu CH, Chen HC, Hsieh JW. An infant with extensive Mongolian spot, naevus flammeus and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita: a unique case of phakomatosis pigmentovascularis. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156: 1068-1071.

13. Abumansour IS, Hijazi H, Alazmi A, et al. ARL6IP6, a susceptibility locus for ischemic stroke, is mutated in a patient with syndromic cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. Hum Genet 2015; 134: 815-822.

14. Dereure O. Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita: mutations in a susceptibility gene involved in cerebrovascular accidents [article in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2016; 143: 96-97.

15. Schuart C, Bassi A, Kapp F, et al. Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita being caused by postzygotic GNA11 mutations. Eur J Med Genet 2022; 65: 104472.

16. Kienast AK, Hoeger PH. Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita: a prospective study of 27 cases and review of the literature with proposal of diagnostic criteria. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009; 34: 319-323.

17. Dermatological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Br J Dermatol 1901; 13: 176-186.

18. Patel DP. The evolving nomenclature of erythema ab igne – redness from fire. JAMA Dermatol 2017; 153: 685.

19. Adams BB. Heated car seat-induced erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol 2012; 148: 265-266.

20. Jagtman BA. Erythema ab igne due to a laptop computer. Contact Dermatitis 2004; 50: 105.

21. Mok DW, Blumgart LH. Erythema ab igne in chronic pancreatic pain: a diagnostic sign. J R Soc Med 1984; 77: 299-301.

22. Hale JM, Chambers F, Connell PRO. Erythema ab igne: an unusual manifestation of cancer-related pain. Pain 2000; 87: 107-108.

23. Hewitt JB, Sherif A, Kerr KM, Stankler L. Merkel cell and squamous cell carcinomas arising in erythema ab igne. Br J Dermatol 1993; 128: 591-592.

24. Corson EF, Knoll GM, Luscombe HA, Decker HB. Role of spectacle lenses in production of cutaneous changes, especially epithelioma. Arch Derm Syphilol 1949; 59: 435-448.

25. Sahl WJ Jr, Taira JW. Erythema ab igne: treatment with 5-fluorouracil cream. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 27: 109-110.

26. Kligman LH, Kligman AM. Reflections on heat.

Br J Dermatol 1984; 110: 369-375.

27. Arrington JH, Lockman DS. Thermal keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma in situ associated with erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol 1979; 115: 1226-1228.

28. Wharton JB, Sheehan DJ, Lesher JL Jr. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Drugs Dermatol 2008; 7: 488-489.

29. Wilder EG, Frieder JH, Menter MA. Erythema ab igne and malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma. Cutis 2021; 107: 51-53.

Skin lesions