Erythema nodosum: presentation and treatment

Erythema nodosum, the most prevalent type of panniculitis, is most frequently seen in women under the age of 40 years. Although a cause is often not identified, its presence warrants consideration of a range of potential triggers and investigation.

- Erythema nodosum (EN) is the most prevalent type of panniculitis. It may be primary (idiopathic) or secondary.

- EN has a strong predilection for women. It can occur at any age but is most common in the second, third and fourth decades of life.

- Most cases of EN spontaneously resolve within three to six weeks. Recurrence can occur, particularly if a cause is not identified.

- Referral to a dermatologist should be arranged for patients with EN that is chronic or recurrent and for patients who have lesions that do not respond to first-line therapy, and is appropriate in the situation of diagnostic uncertainty.

Erythema nodosum (EN), an inflammatory disorder affecting subcutaneous fat, is the most prevalent type of panniculitis in the Australian population.1 The condition has a strong predilection for women and can occur at any age but most commonly presents in the second, third and fourth decades of life.2 Although an underlying cause is often not identified, the presence of EN warrants consideration of a range of potential triggers and investigation as appropriate.

Clinical presentation

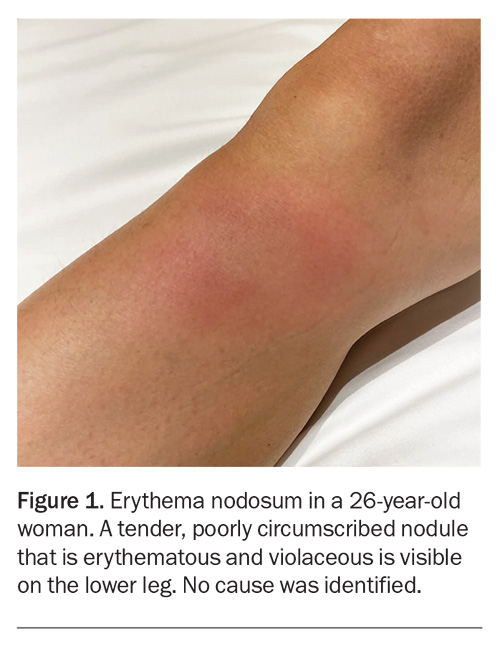

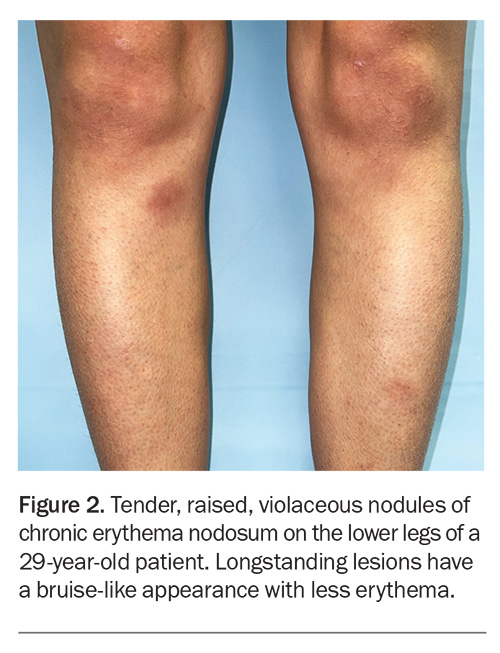

The characteristic presentation of EN is the sudden onset of tender, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules that are distributed symmetrically on the extensor surfaces of the lower limbs (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Patients may experience systemic symptoms, such as fevers, fatigue, malaise and gastrointestinal upset, which can provide clues to triggers.3 Rarely, lesions can occur on the upper limbs, neck or face.2

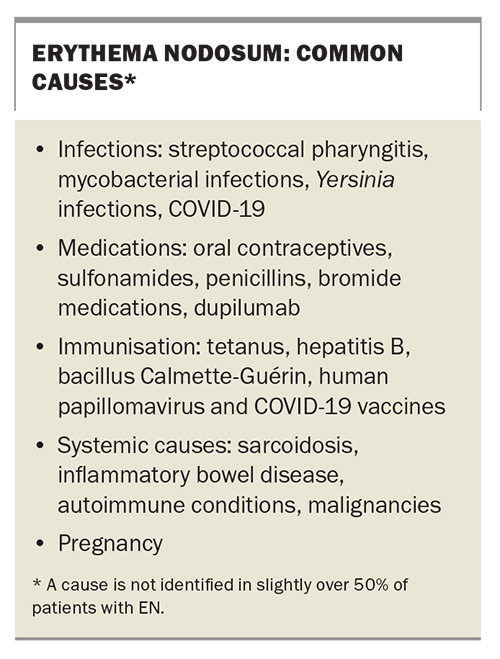

Causes

EN is a type IV delayed reactive hypersensitivity process that has a wide variety of causes (Box).4 It is believed that an antigenic stimulus leads to the formation of immune complexes that are deposited in the septa between subcutaneous fat lobules, which causes inflammation and the development of lesions after three to six weeks.1,3

A preceding streptococcal throat infection is the most frequently found cause of EN, usually in children.5 However, the condition can also be precipitated by other infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis and atypical mycobacterial infections as well as Yersinia infections. An association has recently been found between COVID-19 and EN.4,6

Medications that are most often implicated in EN include the oral contraceptive pill, sulfonamides, penicillins, bromide medications and dupilumab.1,7 Although uncommon, EN has been reported after administration of tetanus, hepatitis B, bacillus Calmette-Guérin, human papillomavirus and COVID-19 vaccines.5,8,9

The systemic causes of EN include sarcoidosis, autoimmune conditions and malignancies. In adults with inflammatory bowel disease, the presence of lesions may precede or correlate with a flare of disease.1 Pregnancy is a known trigger.

Despite extensive investigation, an apparent cause may remain elusive. EN is primary (idiopathic) in slightly over 50% of affected patients, particularly in women of childbearing age.1,3 A causal relationship involving oestrogen has been hypothesised, given its known associations with pregnancy and oral contraceptives.3

Diagnosis and investigation

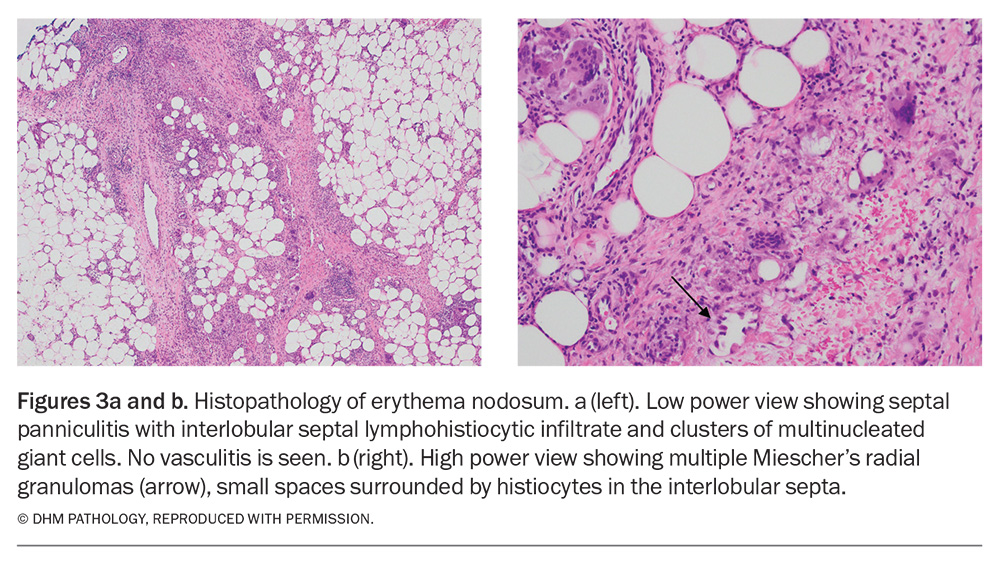

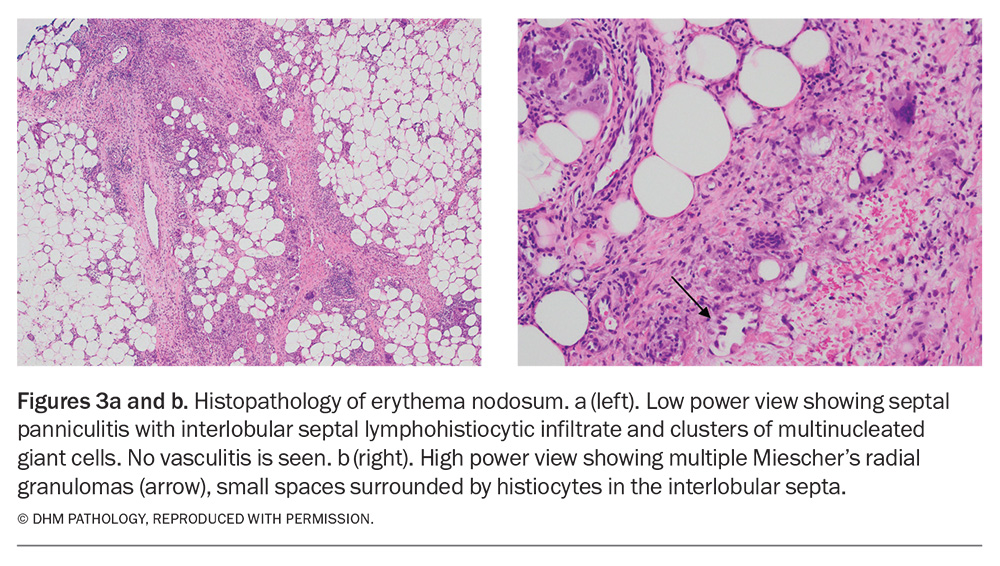

EN is usually diagnosed clinically on the basis of its distinctive appearance. A biopsy is not usually warranted but, if performed, a deep incisional specimen to the level of the subcutaneous fat should be obtained for adequate visualisation.4 Histopathological analysis reveals a characteristic septal panniculitis in the absence of vasculitis (Figure 3a).1,3 In the early stage, neutrophilic infiltration with associated oedema is present; in later stages, there are Miescher’s microgranulomas and septal walls may be thickened and fibrosed (Figure 3b).2,3

It is important to consider causes of secondary EN. Patients with systemic symptoms (fever, sore throat, cough, diarrhoea, arthritis) and patients with elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein [CRP], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]) are likely to have secondary EN, which often resolves when the underlying cause is treated.3 A thorough history should be elicited, which includes autoimmune diseases (including any family history), use of medications and recent vaccinations.1 Potential exposure to unusual infectious agents can be relevant – this may include bites or scratches from pets or exotic animals, recreational activities or hobbies (e.g. diving in tropical water) or overseas travel. In addition, a careful examination of the skin as well as any relevant body systems should be undertaken to help elicit an underlying cause.

Investigations should include a full blood count, liver function tests, and CRP and ESR measurements. If there is clinical suspicion of streptococcal pharyngitis, a throat swab and antistreptolysin-O titre can be ordered. Patients with suspected pulmonary pathology may warrant a chest x-ray to exclude tuberculosis or sarcoidosis.1,3

The nodules of EN tend to regress spontaneously in three to six weeks without scarring, atrophy or ulceration but sometimes leave hyperpigmentation that will resolve over a period of months.1,10 If lesions persist then other types of panniculitis should be considered; biopsy is warranted in this setting.

Management

Management of EN is largely symptomatic. First-line treatment involves bed rest with leg elevation and compression stockings and use of NSAIDs (aspirin, naproxen, indomethacin).1,10 For patients who have severe pain, oral corticosteroids can be used (after infectious causes have been excluded) and provide rapid improvement.1 If identified, any associated condition should be treated and potential culprit medications should be ceased, if reasonable.

Referral

Patients with primary EN are most likely to experience recurrence, which can last months or years.1,3 Referral to a dermatologist for further investigation and management should be arranged for patients with EN that is chronic or recurrent or have lesions that do not respond to first-line therapy. For those with chronic EN or recalcitrant episodes, dapsone, potassium iodide, colchicine and hydroxychloroquine have shown benefit.1,5,10 Referral is also appropriate in the situation of diagnostic uncertainty.

Erythema nodosum in pregnancy

Patients who develop EN during pregnancy should be referred to a dermatologist and consultation with a maternal-fetal medicine specialist considered before starting any medications. Many standard treatments, including NSAIDs and corticosteroids, may be relatively contraindicated, especially in the first trimester, and should be only used with caution in this patient group.11

Conclusion

EN is the most prevalent panniculitis in patients of all ages. The lesions are characteristic in appearance and biopsy is not usually required for diagnosis. The condition may be primary (idiopathic) but it can also be an early sign of an important underlying cause. Most cases resolve within three to six weeks. Patients with primary EN are most likely to experience recurrence; secondary EN often resolves when the underlying cause is treated or removed. Referral to a dermatologist should be considered in certain circumstances, including patients with EN that develops during pregnancy. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr Karen Cheung, dermatopathologist, Douglass Hanly Moir Pathology, NSW, for assistance with the histology images.

References

1. Requena L, Requena C. Erythema nodosum. Dermatol Online J 2002; 8(1): 4.

2. Leung AK, Leong KF, Lam JM. Erythema nodosum. World J Pediatr 2018; 14: 548-554.

3. Mert A, Kumbasar H, Ozaras R, et al. Erythema nodosum: an evaluation of 100 cases. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2007; 25: 563-570.

4. Parker ER, Fitzpatrick A. A case report of COVID-19-associated erythema nodosum: a classic presentation with a new trigger. Fam Pract 2022; 39: 936-938.

5. Sartori DS, Mombelli L, Sartori NS. Erythema nodosum. In: Bonamigo RR (ed). Dermatology in public health environments: a comprehensive textbook, 2nd ed. Cham Switzerland: Springer; 2023. pp. 1709-1718.

6. Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: an international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83: 1118-1129.

7. Mustin DE, Cole EF, Blalock TW, Kuruvilla ME, Stoff BK, Feldman RJ. Dupilumab-induced erythema nodosum. JAAD Case Rep 2022; 19: 41-43.

8. Chahed F, Ben Fadhel N, Ben Romdhane H, et al. Erythema nodosum induced by Covid-19 Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine: a case report and brief literature review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2023; 89: 536-540.

9. Aly MH, Alshehri AA, Mohammed A, et al. First case of erythema nodosum associated with Pfizer vaccine. Cureus 2021; 13(11): e19529.

10. Pérez-Garza DM, Chavez-Alvarez S, Ocampo-Candiani J, Gomez-Flores M. Erythema nodosum: a practical approach and diagnostic algorithm. Am J Clin Dermatol 2021; 22: 367-378.

11. Acosta KA, Haver MC, Kelly B. Etiology and therapeutic management of erythema nodosum during pregnancy: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol 2013; 14: 215-222.