What’s the diagnosis?

A student with an acute eruption of scaly papules and plaques

Case presentation

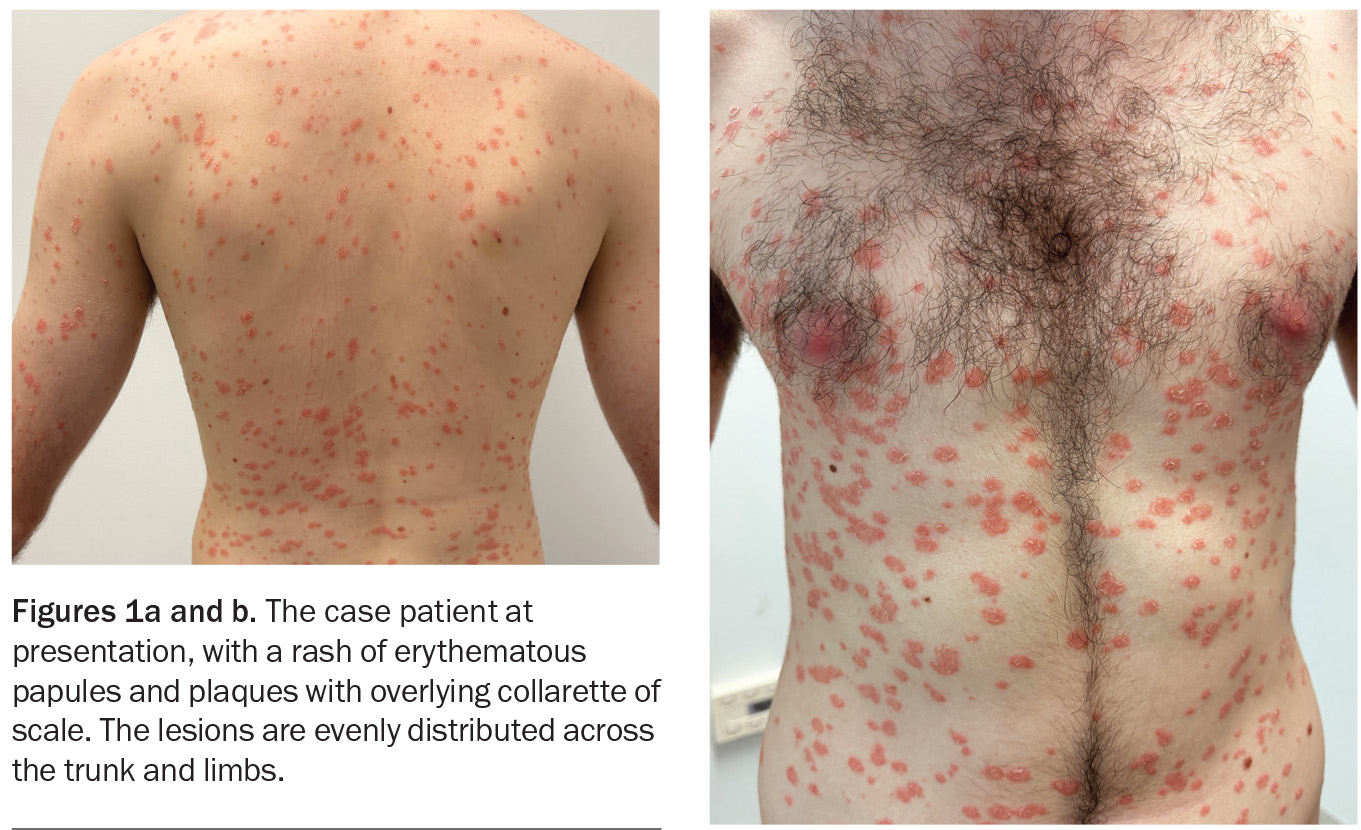

A 22-year-old university student presents with a three-week history of an erythematous, scaly skin eruption (Figures 1a and b). He was systemically unwell with flu-like symptoms and a sore throat one week preceding the eruption but now recovered.

The patient recalls that the eruption started with a single oval plaque on his right upper arm. After a few days, additional lesions appeared on his upper trunk and the eruption then spread to the rest of his body, while sparing the face, palms and soles. He complains of only mild itch. He has treated the eruption with terbinafine hydrochloride 10 mg/g cream and betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% ointment, but there has been no improvement.

The patient has a history of anxiety, for which he takes paroxetine. He does not have a history of skin issues and denies any medication changes prior to the onset of the eruption.

On examination, erythematous, circular papules and plaques are observed in a widespread eruption that is symmetrically distributed over the patient’s chest, back and upper and lower limbs. Most of the plaques have an inner circular edge of scale.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Guttate psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis is an acute variant of psoriasis that is most often seen in children and young adults. It commonly develops one to three weeks after a group A streptococcal (Streptococcus pyogenes) upper respiratory tract infection or tonsillitis.1 Other triggers for guttate psoriasis have been reported, including coxsackie A virus infection and COVID-19.2,3 Guttate psoriasis often occurs in individuals with no prior history of psoriasis, but in some cases it can represent an acute flare of pre-existing chronic plaque psoriasis.4

Guttate psoriasis typically presents as numerous ‘raindrop-like’ erythematous papules and plaques over the trunk and limbs. There may be an overlying diffuse white-grey scale, although this can be subtle in early lesions. Pruritus is not always present.5

A diagnosis of guttate psoriasis is usually made clinically without a skin biopsy. Blood tests may be requested, specifically antistreptolysin O and anti-DNase B titres, with positive serology indicating a recent streptococcal infection supporting a diagnosis of guttate psoriasis.

Around one-quarter of patients go on to develop chronic plaque psoriasis later in life.6 This risk is increased if guttate psoriasis persists for more than one year.6

For the case patient, the arrangement of overlying scale in an inner collarette pattern, rather than being diffuse over the lesions, was more consistent with an alternative diagnosis than guttate psoriasis.

Secondary syphilis

Secondary syphilis, a disseminated form of syphilis, is caused by Treponema pallidum. Syphilis in adults is usually sexually transmitted.7 In Australia, syphilis particularly affects homosexual and bisexual men, and a recent study found that 82% of reported cases were men.8 However, syphilis can affect people of all ages, including children through vertical transmission from mothers who have the infection.9

Secondary syphilis typically occurs two to 10 weeks after untreated primary syphilis, which may present as a painless chancre that appears up to three months after initial exposure.10 The characteristic skin manifestation of secondary syphilis is an erythematous maculopapular eruption, which may involve the extremities (commonly affecting the palms and soles), trunk and mucous membranes. Systemic symptoms often accompany the skin signs, and include lymphadenopathy, fever, diffuse hair loss, headaches, fatigue and muscle and joint aches.7,10

A diagnosis of syphilis can be made directly by polymerase chain reaction testing of a swab specimen taken from a lesion or by dark-field microscopy for visualising the white spirochete T. pallidum on a black background.11 Serological testing is commonly used – a diagnosis requires positive results for both nontreponemal tests (Venereal Disease Research Laboratories [VDRL] or rapid plasma reagin [RPR]) and treponemal tests (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption [FTA-Abs] or T. pallidum particle agglutination [TPPA]).11

For the case patient, a diagnosis of secondary syphilis was unlikely because he was systemically well at presentation and his skin eruption spared the acral surfaces. He also denied any recent sexual contact with a new partner.

Mycosis fungoides

Mycosis fungoides is the most common primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, a form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It can affect any age group but the incidence increases significantly with age and the median age at diagnosis is in the mid-50s.12 The aetiology remains unknown, but current hypotheses include a role for genetic predisposition and environmental triggers, such as exposure to certain chemicals and medications.13

Mycosis fungoides is classically a slowly progressive disease with three separate stages: patch, plaque and tumour. Progression from one stage to the next is extremely variable and may develop over months to years.14 The patch stage is characterised by erythematous, irregular patches located on sun-protected areas. This progresses to the plaque stage, when lesions are darker in colour, well-demarcated, pruritic and thickened. Lastly, the tumour stage is characterised by large, irregular cutaneous tumours which can be deep red to violaceous in colour.

The diagnosis of mycosis fungoides is based on both clinical and pathological features and can be difficult in early disease. Serial skin biopsies are usually required to establish the nature of the disease process over time.15 If suspected, other investigations may be required for staging – these include blood tests, lymph node biopsy, radiological imaging and bone marrow biopsy.

For the case patient, the acute onset of the widespread papules and plaques did not fit with a diagnosis of mycosis fungoides.

Tinea corporis

Tinea corporis is a dermatophyte infection usually caused by anthropophilic species of dermatophytes, most commonly Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton tonsurans, and, less often, by zoophilic species such as Microsporum canis.16 The infection spreads through direct contact with infected individuals, animals or contaminated objects. It is more prevalent in warm, humid climates.17

Tinea corporis is also known as ‘ringworm’, a misnomer that describes how the annular lesions often spread centrifugally and form a central clearing with a raised, active, scaly border (‘ring’) on the leading edge.18 Typical lesions are well-demarcated patches or plaques that are mildly erythematous, annular and scaly with associated mild pruritus. The lesions may be distributed anywhere but usually exclude the scalp, palms and soles.

The diagnosis of tinea corporis is typically clinical, based on the characteristic appearance of the lesions. Confirmatory tests include microscopic examination of skin scrapings treated with potassium hydroxide to reveal dermatophyte hyphae as linear and/or branching structures; fungal culture can be used to identify the causative organism.19 Skin biopsy reveals foci of parakeratosis with epidermal acanthosis, spongiosis and neutrophils in the upper epidermis, and oedema and chronic inflammatory changes in the dermis.20

Although the initial oval plaque for the case patient may have been mistaken for tinea corporis, this was not the correct diagnosis as the subsequent lesions did not have a central clearing.

Pityriasis rosea

This is the correct diagnosis. Pityriasis rosea is a relatively common acute disease that mainly affects children and young adults. The aetiology is still unknown, but suggested causes have included viral and bacterial infections, as well as noninfective factors such as medications, vaccines, atopy and autoimmunity.21 Recent speculation has centred on the reactivation of a latent virus, in particular human herpesviruses 6 and 7.22 Up to 69% of patients have systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, cough and sore throat for a few days before the herald patch appears.23 However, this prodromal illness usually subsides at the onset of the eruption.

The first skin manifestation is usually the appearance of a herald patch, which is a sharply defined, erythematous, round or oval plaque, between 2 and 10 cm in size, with a peripheral collarette of scale. A few days or weeks later, the secondary rash appears with lesions that are sharply demarcated, pink, oval papules and plaques covered by a fine scale. The scale often lags behind the leading edge like a peripheral collarette with central clearing, which is known as the ‘trailing’ or ‘hanging curtain’ sign.24 This eruption typically affects the trunk, upper arms and upper thighs and is often described as forming a ‘Christmas tree-like’ pattern on the upper chest and back as it follows the relaxed skin tension lines. Pruritus is variable and, if present, usually mild and tolerable.25

Pityriasis rosea is usually a clinical diagnosis. A skin biopsy is not generally required but, if performed, will reveal nonspecific histopathological features. These consist of focal parakeratosis in the epidermis, with variable spongiosis, mild acanthosis and a thinned granular layer.25 Features in the dermis include extravasated red blood cells and a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and eosinophils. In around 55% of cases, dyskeratotic degeneration of epidermal cells is seen.26

Management

Pityriasis rosea is a self-limiting disease, with skin lesions usually fading after six to eight weeks in more than 80% of patients.27 Skin discolouration may persist for longer, especially in darker-skinned people. Treatment involves providing patients with information and reassurance about the self-limiting nature of the condition and supportive management of pruritus, if present. This includes general skincare advice about showering (short duration, lukewarm water and a soap-free cleanser) and applying a bland emollient at least once daily. Medium potency topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines may help to reduce pruritus.28,29

In extensive or persistent cases, narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy, administered two or three times per week, may be considered. Phototherapy is very well tolerated and may be continued until a significant improvement is seen on review.30

Although previously proposed as an alternative treatment option, the role of macrolide antibiotics remains unclear and they are not used in routine clinical practice.31 In severe cases, oral aciclovir 400 mg three to five times per day for a total of seven days has been shown to lead to improvements in symptoms and faster resolution of lesions.32 However, in practice, aciclovir is rarely used or indicated.

Outcome

The case patient was given a clinical diagnosis of pityriasis rosea. He was advised to stop using topical terbinafine and to switch the topical corticosteroid to methylprednisolone aceponate 0.1% fatty ointment daily. He was given skincare advice about showering and use of a bland emollient once or twice daily. On review after six weeks, his eruption had almost completely faded with resolution of symptoms. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Telfer NR, Chalmers RJ, Whale K, Colman G. The role of streptococcal infection in the initiation of guttate psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 1992; 128: 39-42.

2. Rychik KM, Yousefzadeh N, Glass AT. Guttate psoriasis following presumed coxsackievirus A. Cutis 2019; 104: 248-249.

3. Gananandan K, Sacks B, Ewing I. Guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep 2020; 13: e237367.

4. Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol 1996; 132: 717-718.

5. Ko HC, Jwa SW, Song M, Kim MB, Kwon KS. Clinical course of guttate psoriasis: long-term follow-up study. J Dermatol 2010; 37: 894-899.

6. Pfingstler LF, Maroon M, Mowad C. Guttate psoriasis outcomes. Cutis 2016; 97: 140-144.

7. Wöhrl S, Geusau A. Clinical update: syphilis in adults. Lancet 2007; 369: 1912-1914.

8. King J, McManus H, Gray R, McGregor S. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia: annual surveillance report 2021. Sydney: Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney; 2021.

9. Cooper JM, Sánchez PJ. Congenital syphilis. Semin Perinatol 2018; 42: 176-184.

10. Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis 1980; 7: 161-164.

11. Satyaputra F, Hendry S, Braddick M, Sivabalan P, Norton R. The laboratory diagnosis of syphilis. J Clin Microbiol 2021; 59: 10.1128/jcm.00100-21.

12. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973-2002. Arch Dermatol 2007; 143: 854-859.

13. Hristov AC, Tejasvi T, Wilcox RA. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 2019; 94: 1027-1041.

14. Bhabha FK, McCormack C, Wells J, et al. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: Australian clinical practice statement. Australas J Dermatol 2021; 62: e8-e18.

15. Massone C, Kodama K, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Histopathologic features of early (patch) lesions of mycosis fungoides: a morphologic study on 745 biopsy specimens from 427 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 2005; 29: 550-560.

16. Gupta AK, Chaudhry M, Elewski B. Tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea nigra, and piedra. Dermatol Clin 2003; 21: 395-400.

17. Sahoo AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: a comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J 2016; 7: 77-86.

18. Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Stone MS. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician 2014; 90: 702-710.

19. Richardson MD. Diagnosis and pathogenesis of dermatophyte infections. Br J Clin Pract Suppl 1990; 71: 98-102.

20. Park YW, Kim DY, Yoon SY, et al. ‘Clues’ for the histological diagnosis of tinea: how reliable are they? Ann Dermatol 2014; 26: 286-288.

21. Mahajan K, Relhan V, Relhan AK, Garg VK. Pityriasis rosea: an update on etiopathogenesis and management of difficult aspects. Indian J Dermatol 2016; 61: 375-384.

22. Kosuge H, Tanaka-Taya K, Miyoshi H, et al. Epidemiological study of human herpesvirus-6 and human herpesvirus-7 in pityriasis rosea. Br J Dermatol 2000; 143: 795-798.

23. Sharma PK, Yadav TP, Gautam RK, Taneja N, Satyanarayana L. Erythromycin in pityriasis rosea: a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42(2 Pt 1): 241-244.

24. Adya KA, Inamadar AC, Palit A. Dermatoses with “collarette of skin”. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2019; 85: 116-124.

25. Drago F, Broccolo F, Rebora A. Pityriasis rosea: an update with a critical appraisal of its possible herpesviral etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 61: 303-318.

26. Okamoto H, Imamura S, Aoshima T, Komura J, Ofuji S. Dyskeratotic degeneration of epidermal cells in pityriasis rosea: light and electron microscopic studies. Br J Dermatol 1982; 107: 189-194.

27. Cheong W, Wong K. An epidemiological study of pityriasis rosea in Middle Road Hospital. Singapore Med J 1989; 30: 60-62.

28. Chuh AA, Dofitas BL, Comisel G, et al. Interventions for pityriasis rosea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (2): CD005068.

29. Contreras-Ruiz J, Peternel S, Jiménez Gutiérrez C, Culav-Koscak I, Reveiz L, Silbermann-Reynoso M. Interventions for pityriasis rosea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019; (10): CD005068.

30. Jairath V, Mohan M, Jindal N, et al. Narrowband UVB phototherapy in pityriasis rosea. Indian Dermatol Online J 2015; 6: 326-329.

31. Pandhi D, Singal A, Verma P, Sharma R. The efficacy of azithromycin in pityriasis rosea: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2014; 80: 36-40.

32. Das A, Sil A, Das NK, Roy K, Das AK, Bandyopadhyay D. Acyclovir in pityriasis rosea: an observer-blind, randomized controlled trial of effectiveness, safety and tolerability. Indian Dermatol Online J 2015; 6: 181-184.

Skin lesions