What’s the diagnosis?

A teenage boy with patchy hair loss after a haircut

Case presentation

A 14-year-old boy presents with a 12-month history of hair loss on his scalp. The hair loss began after a haircut at a barber shop and has been gradually worsening, with the affected areas becoming mildly itchy.

The patient is otherwise well. He has no significant medical history and is not taking any regular medications. He lives with his family, who are all well and not showing any skin or hair changes.

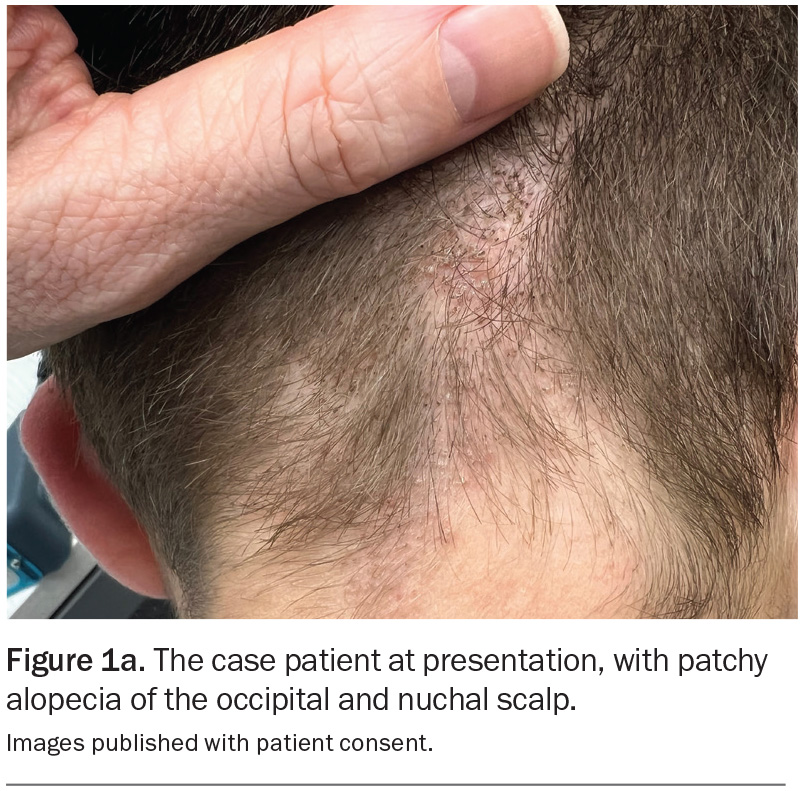

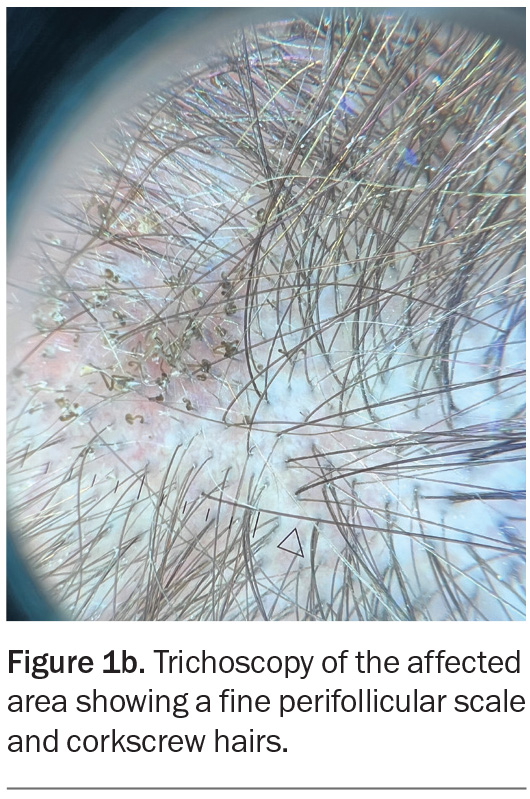

On examination, patchy alopecia is observed on the patient’s occipital and nuchal scalp (Figure 1a). The affected areas are mildly erythematous with overlying scale and speckled with black dots. Trichoscopy reveals fine perifollicular scale as well as comma, corkscrew and zigzag hairs (Figure 1b). The remainder of the examination is unremarkable.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Scalp psoriasis

Scalp psoriasis, which affects individuals of all age groups and both genders, is seen in about 80% of people with psoriasis.1 A chronic inflammatory condition in genetically predisposed individuals, psoriasis is a T-cell immune-mediated disorder that leads to hyperproliferation of keratinocytes, resulting in thickened skin and scale. Environmental triggers, which include stress, smoking, alcohol, infections and certain medications, can exacerbate the condition.2 It is particularly common in Caucasians and about one-third of patients have a family history of the condition.3

Scalp psoriasis typically presents as erythematous, scaly plaques on any part of the scalp, but it can extend to the hairline, forehead, nape of the neck, and area behind the ears.4 The plaques may be covered with thick, silvery-white scale that can lead to noticeable flaking resembling dandruff. Patients may complain of pruritus or, in severe cases, localised alopecia.5

The diagnosis is primarily clinical. Scalp psoriasis can occur in isolation or with other manifestations of psoriasis – nail pits, onycholysis and oil spots, as well as hyperkeratosis over the extensors, can be useful clues. A scalp biopsy is usually not required but, if performed, a histological examination shows parakeratosis, acanthosis and inflammatory infiltrates.6

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, who did not have erythematous plaques with silvery white scale on his scalp and no manifestations elsewhere to suggest psoriasis.

Discoid lupus erythematosus

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), the most common subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, is an autoimmune condition with both genetic and environmental aetiology. It can affect both males and females and occurs in people of any age but is most commonly seen in young

to middle-aged women and patients

with skin of colour and certain ethnicity (African, Asian and Hispanic descent). Risk factors include a history of smoking,

certain medications, preceding viral infections, stress and a personal or family history of other autoimmune diseases.7 Ultraviolet light exposure is an important trigger because DLE is a photosensitive disorder.8

DLE presents as well-defined erythematous patches or plaques commonly affecting sun-exposed areas. As the condition progresses, the lesions can develop atrophic scarring that presents as hyper- or hypopigmentation. Scalp involvement has been reported in around 60% of patients with DLE.9 Scalp plaques have adherent, thick scale that may cause follicular hyperkeratosis and can lead to destruction of the hair follicles, resulting in scarring alopecia.10 Patients may complain of pruritus or tenderness and notice that lesions tend to worsen with sun exposure.8

A scalp biopsy may be performed to confirm a diagnosis of DLE, showing epidermal atrophy, follicular plugging, basal cell degeneration and a lymphocytic infiltrate around hair follicles.11 Direct immunofluorescence testing of lesional skin will frequently reveal immune complex deposition at the dermoepidermal junction.

Although DLE often remains localised to the skin, between 5 and 15% of patients develop systemic lupus erythematosus.12 Serological testing for autoimmune diseases, such as the antinuclear antibody (ANA) and extractable nuclear antigen (ENA), is often performed to assess for systemic involvement but is frequently negative in patients who have isolated cutaneous DLE.13

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. Trichoscopy revealed nonscarring alopecia and did not show any follicular plugging. In addition, he did not have any risk factors for an autoimmune aetiology.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is a common inflammatory skin condition affecting people of all ages and ethnicities.14 The aetiology is believed to be multifactorial, involving a complex interplay of genetic predisposition, immune response and hormonal factors. Colonisation of the skin by the commensal yeast Malassezia species is believed to be pivotal in the pathogenesis, stimulating inflammation that precipitates flares of seborrhoeic dermatitis.15 Triggers include cold weather, stress, nutritional deficits (e.g. B-group vitamins, zinc, essential fatty acids and vitamin D), hormonal changes, immunosuppression and certain medications (e.g. immunosuppressants, antipsychotics, lithium and androgenic medications), as well as some neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy.16,17

Seborrhoeic dermatitis presents as poorly defined, erythematous, scaly patches with little or no pruritus.18 On the scalp, there are often greasy, thin, yellowish scales that may adhere to hair shafts. There is no associated scarring or permanent hair loss. In adults, seborrhoeic dermatitis mainly affects areas that are rich in sebaceous glands, such as the face (especially the eyebrows, glabella, nasolabial folds and skin around the ears), scalp, axilla, chest, genitals (pubic area, perianal region, the labia majora in females and the scrotum in men) and the skin folds. In infants, the condition usually affects the scalp (cradle cap), axilla and groin folds.

The diagnosis of seborrhoeic dermatitis is primarily based on the clinical characteristics. Trichoscopy reveals thin, yellowish scales and diffuse erythema.19 If the diagnosis is unclear, a scalp biopsy may be performed and will typically reveal parakeratosis, spongiosis and mild perivascular infiltrates; however, this is seldom required.20

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. The typical yellowish scaling was not present and would not explain the corkscrew hairs.

Tinea capitis

This is the correct diagnosis. Tinea capitis is an infection of the scalp and hair caused by dermatophytic fungi, primarily from the Trichophyton and Microsporum genera.

In Australia, the most common causative species are Microsporum canis (zoophilic) and Trichophyton tonsurans (anthropophilic).21 Tinea capitis is contagious and can be spread by direct contact with an infected person or via contaminated objects, such as hairbrushes, hats, pillows, towels and furniture, where the fungal spores may remain viable for months.22 In addition, zoophilic fungi can be transmitted from infected animals, including pets: M. canis can be acquired through contact with an infected cat or kitten and Trichophyton mentagrophytes is commonly associated with guinea pigs.

Although tinea capitis affects people of all ages, it is primarily seen in young children. Risk factors include crowded living conditions, communities where people are in close contact (e.g. schools), poor hygiene, warm humid environments and animal contact.23 Tinea capitis can be linked to barbershops, especially if proper hygiene practices are not maintained.

The clinical features of tinea capitis depend on the causative species and host inflammatory response. The most common presentation is a fine scaly patch on the scalp with associated alopecia. The area may be erythematous (which may be minimal or pronounced) or grey in colour. Itch and tenderness are variable and depend on the level of inflammation. Other presentations include kerion (a painful, erythematous and boggy plaque with associated alopecia and pustules) and favus (yellow, crusted areas associated with matted hair).

Trichoscopy is a useful tool in the diagnosis of tinea capitis.24,25 Common findings include the following:

- comma-shaped hairs, which are curved and broken

- black dots (hairs that are broken at the level of the scalp)

- corkscrew hairs (spiral-shaped), which are commonly seen in cases caused by Trichophyton species

- zigzag hairs, with several bends

- morse code-like hairs (irregularly broken hair shafts that resemble dashes and dots)

- scaling, which may be diffuse, fine, yellowish, grey or white (perifollicular and/or coating affected hairs)

- perifollicular erythema.

A diagnosis of tinea capitis is based on findings from the clinical examination and confirmed by laboratory investigations. A Wood’s lamp examination can be helpful, as certain Microsporum species fluoresce bright green under ultraviolet light.26 However, not all causative fungi (including most Trichophyton species) fluoresce, so a negative Wood’s lamp test does not rule out a diagnosis of tinea capitis.

Microscopy and culture are recommended.24 Scrapings of scalp and scale scrapings and plucked hairs are easy to collect for testing. A diagnosis of tinea capitis is confirmed by visualisation of hyphae and spores in a potassium hydroxide preparation and the specific organism identified by fungal culture, which can take up to four weeks. Treatment should not be delayed, but the results of fungal culture can help to guide management if the patient is not responding to empirical therapy.

Management

The mainstay of treatment for tinea capitis is systemic antifungal therapy. Topical antifungal preparations are generally ineffective because they do not penetrate the hair follicles where the infection is located. First-line therapy is griseofulvin 500 mg daily (or 10 to 20 mg/kg daily in children) for six to eight weeks.27 Alternatively, terbinafine 250 mg daily (or 62.5 mg daily in children under 20 kg and 125 mg daily in children 20 to 40 kg) for four weeks can also be prescribed.27 Griseofulvin is more effective for Microsporum whereas terbinafine is more effective for Trichophyton. For patients who cannot tolerate griseofulvin or terbinafine and patients who have extensive or refractory cases of tinea capitis, itraconazole or fluconazole may be selected.28

Adjunctive topical therapies are often recommended to reduce fungal spore shedding and risk of reinfection. Antifungal shampoos containing ketoconazole or selenium sulfide should be used two to three times weekly during the course of treatment.29

The patient’s close contacts, particularly household members, should be screened and treated if necessary.28 Patients and caregivers should be educated about hygiene practices and the contagious nature of the condition. To prevent spread, items that are in contact with the hair (including hair grooming tools, hats and pillows) should be thoroughly cleaned and not shared with other people. In cases of zoophilic infection, the family pets should be checked by a veterinarian.

Outcome

A clinical diagnosis of tinea capitis was made and the patient commenced empirical treatment with terbinafine 250 mg daily for four weeks. This agent was chosen because a Trichophyton species was suspected to be the causative organism, in light of contact with a barbershop. The diagnosis was explained and he was educated about the importance of cleaning his hair grooming tools, hats and pillows and not sharing these with others until his condition resolved. For hair washing, he was advised to use a shampoo containing 2% ketoconazole. None of his family members showed signs of tinea capitis. The diagnosis was confirmed by light microscopy and the result of fungal culture, returned four weeks later, confirmed the growth of T. tonsurans. Eight weeks later, the patient had no signs of infection and his hair regrowth was excellent. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, Menter A, Stern RS, Rolstad T. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol 2001; 137: 280-284.

2. Huerta C, Rivero E, Rodríguez LAG. Incidence and risk factors for psoriasis in the general population. Arch Dermatol 2007; 143: 1559-1565.

3. Naldi L, Parazzini F, Brevi A, et al. Family history, smoking habits, alcohol consumption and risk of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 1992; 127: 212-217.

4. van de Kerkhof PC, Franssen ME. Psoriasis of the scalp: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2001; 2: 159-165.

5. George SMC, Taylor MR, Farrant PBJ. Psoriatic alopecia. Clin Exp Dermatol 2015; 40: 717-721.

6. Murphy M, Kerr P, Grant-Kels JM. The histopathologic spectrum of psoriasis. Clin Dermatol 2007; 25: 524-528.

7. Yavuz G, Yavuz I, Bayram I, Aktar R, Bilgili S. Clinic experience in discoid lupus erythematosus: a retrospective study of 132 cases. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2019; 36: 739-743.

8. Foering K, Chang AY, Piette EW, Cucchiara A, Okawa J, Werth VP. Characterization of clinical photosensitivity in cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 69: 205-213.

9. Udompanich S, Chanprapaph K, Suchonwanit P. Hair and scalp changes in cutaneous and systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Clin Dermatol 2018; 19: 679-694.

10. Wilson CL, Burge SM, Dean D, Dawber RP. Scarring alopecia in discoid lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 1992; 126: 307-314.

11. Fabbri P, Amato L, Chiarini C, Moretti S, Massi D. Scarring alopecia in discoid lupus erythematosus: a clinical, histopathologic and immunopathologic study. Lupus 2004; 13: 455-462.

12. Elman SA, Joyce C, Costenbader KH, Merola JF. Time to progression from discoid lupus erythematosus to systemic lupus erythematosus: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Experimental Dermatol 2020; 45: 89-91.

13. Chong B, Song J, Olsen N. Determining risk factors for developing systemic lupus erythematosus in patients with discoid lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166: 29-35.

14. Polaskey MT, Chang CH, Daftary K, Fakhraie S, Miller CH, Chovatiya R. The global prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2024; 160: 846-855.

15. Kim GK. Seborrheic dermatitis and malassezia species: how are they related? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2009; 2: 14-17.

16. Kim KM, Kim HS, Yu J, Kim JT, Cho SH. Analysis of dermatologic diseases in neurosurgical in-patients: a retrospective study of 463 cases. Ann Dermatol 2016; 28: 314-320.

17. Wilkowski CM, Alhajj M, Kilbane CW, Kumar Y, Bordeaux JS, Carroll BT. The association of seborrheic dermatitis and Parkinson’s disease: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2024; doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2024.08.074.

18. Gupta A, Bluhm R. Seborrheic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2004; 18: 13-26.

19. Golińska J, Sar-Pomian M, Rudnicka L. Diagnostic accuracy of trichoscopy in inflammatory scalp diseases: a systematic review. Dermatology 2022; 238: 412-421.

20. Park J-H, Park YJ, Kim SK, et al. Histopathological differential diagnosis of psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp. Ann Dermatol 2016; 28: 427-432.

21. Gupta AK, Summerbell RC. Tinea capitis. Med Mycol 2000; 38: 255-287.

22. Leung AKC, Hon KL, Leong KF, Barankin B, Lam JM. Tinea capitis: an updated review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2020; 14: 58-68.

23. Rodríguez-Cerdeira C, Martínez-Herrera E, Szepietowski JC, et al. A systematic review of worldwide data on tinea capitis: analysis of the last 20 years. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35: 844-883.

24. Elewski BE. Tinea capitis: a current perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000 (1 Pt 1); 42: 1-20.

25. Waśkiel-Burnat A, Rakowska A, Sikora M, Ciechanowicz P, Olszewska M, Rudnicka L. Trichoscopy of tinea capitis: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2020; 10: 43-52.

26. Halprin KM. Diagnosis with Wood’s light: tinea capitis and erythrasma. JAMA 1967; 199: 841.

27. Ellis D, Watson A. Systemic antifungal agents for cutaneous fungal infections. Australian Therapeutic Guidelines. Available online at: https://australianprescriber.tg.org.au/articles/systemic-antifungal-agents-for-cutaneous-fungal-infections.html (accessed December 2024).

28. Kovitwanichkanont T, Chong AH. Superficial fungal infections. Aust J Gen Pract 2019; 48: 706-711.

29. Gupta AK, Hofstader SL, Adam P, Summerbell RC. Tinea capitis: an overview with emphasis on management. Pediatr Dermatol 1999; 16: 171-189.

Fungal infections