What’s the diagnosis?

A woman with hair loss and nail changes

Case presentation

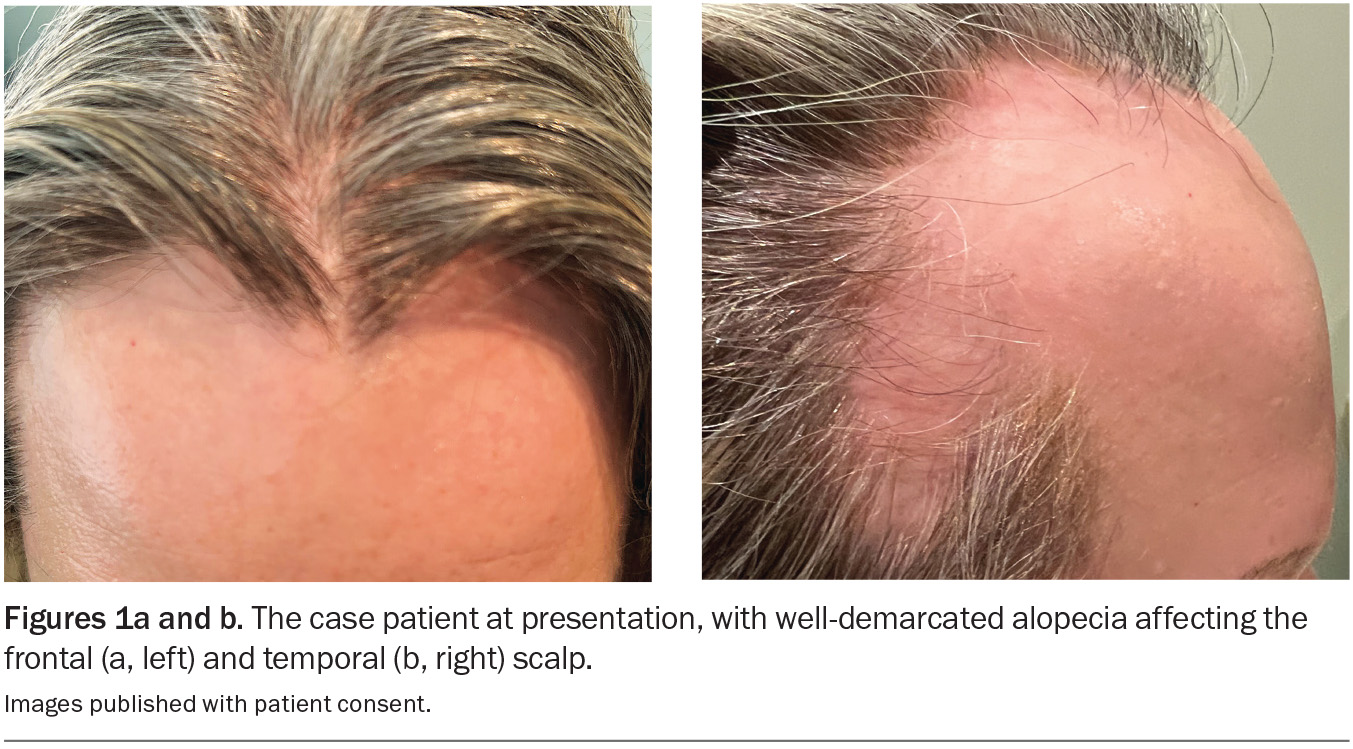

A 43-year-old woman presents with generalised hair loss that has been gradually worsening over the past year. The loss of hair is most prominent on the front and sides of her scalp and has significantly affected her self-confidence and social life.

The patient has a history of hypothyroidism, which is treated with thyroxine, and chronic plaque psoriasis, which is well controlled with a combination calcipotriol/betamethasone ointment. She is a nonsmoker and drinks alcohol on occasion.

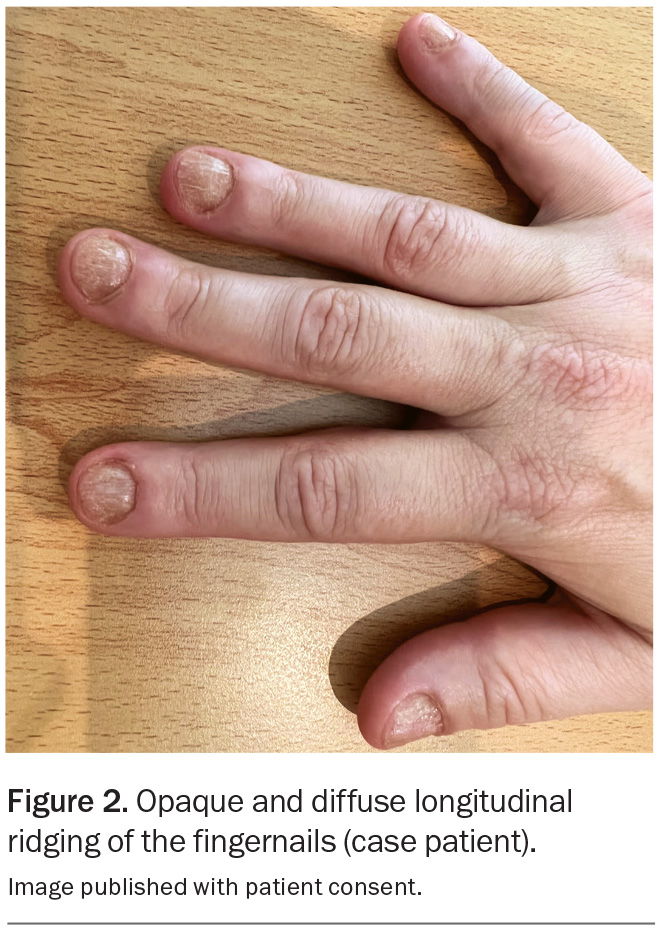

On examination, well-demarcated bilateral areas of hair loss are observed on the frontotemporal scalp (Figures 1a and b). Trichoscopy reveals ‘exclamation mark’ hairs and yellow dots, but no scale is visible on the scalp or the hairs in surrounding areas. Bilateral eyebrow thinning is noted, and she has no eyelashes. Examination of the fingernails reveals opaque and diffuse longitudinal ridging affecting all 10 nails, which makes them rough to touch, and the patient complains that they are thin and brittle (Figure 2).

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia

The incidence of frontal fibrosing alopecia, a type of scarring alopecia, is increasing worldwide. The condition affects women and men of all age groups and ethnic backgrounds but is most common in postmenopausal Caucasian women.1 Commonly considered a variant of lichen planopilaris, its exact cause is unknown but thought to involve autoimmune, genetic, hormonal and environmental factors.2

Frontal fibrosing alopecia can affect any area of the body but usually presents with progressive receding of the frontal hairline, often with associated eyebrow thinning or loss.3 Comparing upper and lower areas of the forehead can be useful for determining whether the hairline has changed because areas where there was previously hair growth will show less sun damage. The areas of alopecia may appear smooth, shiny and atrophied, indicating scarring, and there may be single lone hairs persisting. On trichoscopy, there is absence of hair follicular openings and, during the active phase of the disease, there may be perifollicular erythema and scaling.2 Early symptoms include mild itching and/or burning sensations, which may occur before any obvious hair loss.3

Although there are characteristic clinical and trichoscopic features of frontal fibrosing alopecia, a scalp biopsy is often performed to confirm the diagnosis. The typical histological findings include a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate and fibrosis.4

For the case patient, the trichoscopic findings and nail changes did not correlate with a diagnosis of frontal fibrosing alopecia.

Female pattern hair loss

Female pattern hair loss (androgenetic alopecia) is the most common form of diffuse hair loss in women. The incidence increases with age, with around 40% of women over the age of 50 years experiencing some degree of hair thinning.5 There is a strong genetic predisposition.6

Female pattern hair loss will typically present as diffuse thinning of hair on the crown and frontal scalp, which leads to a widened central parting in a ‘Christmas tree’ pattern as the condition progresses.7 Patients often complain of increased hair shedding that results in reduced hair volume. The hair loss activity may fluctuate, with periods of accelerated shedding followed by longer periods of relative stability. On trichoscopy, there are miniaturised follicles and hairs with a much smaller diameter and length.8

Female pattern hair loss is usually a clinical diagnosis, based on the characteristic pattern of hair thinning. The majority of women affected do not have hormonal abnormalities, so hormone level testing is not performed routinely.

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, who did not have the characteristic hair thinning pattern.

Trichotillomania

Trichotillomania is a psychiatric condition characterised by recurrent and compulsive pulling of an individual’s own hair, leading to noticeable alopecia. It is characterised as a body-focused repetitive behaviour and often develops as a coping mechanism associated with other mental health disorders, such as anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder.9 It affects between 0.5 and 2% of the general population and is more common in children and adolescents than adults.10

Clinically, trichotillomania generally presents as irregular, patchy alopecia in areas where the hair was previously easily accessible for pulling – most commonly the scalp (same side as the dominant hand), eyebrows and eyelashes. The patterns of alopecia can vary broadly, from mild thinning to completely bald patches. Hair of varying lengths may be present in affected areas, due to partial or incomplete pulling. Secondary skin lesions may be seen, including excoriations, erythema and bruises from picking. Trichoscopy may reveal fractured hair shafts.11

The diagnosis of trichotillomania is primarily clinical. Patients may or may not acknowledge or be aware of their hair-pulling behaviour. The condition often leads to significant emotional distress and embarrassment. Referral for evaluation by a psychologist or psychiatrist may be necessary.

Trichotillomania was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, whose hair loss and nail changes correlated with a different diagnosis.

Alopecia areata

This is the correct diagnosis. Alopecia areata is an autoimmune disorder in which the immune system mistakenly attacks hair follicles, leading to nonscarring alopecia. The aetiology is believed to involve an environmental trigger (such as stress, pollution or chemicals) in a genetically predisposed individual.12 Alopecia areata most commonly presents before the age of 30 years and affects people of all genders and ethnic backgrounds. Risk factors include other autoimmune conditions (such as vitiligo, lupus, thyroid disease), atopic dermatitis and chromosomal disorders (such as Down syndrome), as well as a family history of the condition.13,14

Alopecia areata typically presents as well-demarcated patches of alopecia where the skin appears normal, without scarring or scaling. Besides the scalp, other affected areas include the beard, eyebrows and eyelashes. On trichoscopy, ‘exclamation mark’ hairs (strands that taper at the base) are characteristic, particularly at the periphery of the bald patches; other features include black and yellow dots and short broken hairs.15 A positive hair pull test at the periphery of the bald patches (>10% of grasped hairs easily pulled out) can indicate active disease. Most patients are asymptomatic but some experience localised tingling, burning or pruritus.16

More severe widespread cases are rare, including alopecia totalis (complete loss of scalp hair) or alopecia universalis (loss of all body hair). Nail changes, which occur in 10 to 40% of patients, are usually associated with more severe disease.17 These include:

- nail pitting (small pinpoint depressions)

- trachyonychia (rough and brittle nails with diffuse longitudinal ridging), which may be opaque

- onycholysis (nail separation from the nail bed)

- leukonychia (white spots).

Alopecia areata is usually diagnosed clinically, but a scalp biopsy can be performed if the diagnosis is unclear. Characteristic findings on histological examination include dense peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrates in the acute phase and follicle miniaturisation with progression of the disease.18 Blood tests for associated autoimmune conditions may be undertaken if indicated by symptoms, but routine screening is not recommended.

Management

The management of alopecia areata is tailored to the severity and extent of the disease, and may be influenced by patient preference. For patients with mild disease and small patches of hair loss, potent topical corticosteroids may be prescribed to encourage regrowth. Topical 5% minoxidil foam or solution can also be used, usually in combination with topical corticosteroids.19 Intralesional corticosteroid therapy, however, is more likely to be effective than topical options – this most commonly involves injections of triamcinolone acetonide 5 mg/mL, repeated four to six weekly until regrowth is complete.19

In patients with alopecia areata that is more severe or extensive and/or resistant to initial treatment, systemic immunosuppressive medications can be considered. Methotrexate has been shown to be effective in both adult and paediatric patients for whom topical and intralesional corticosteroid therapy has failed.20 Oral corticosteroids are generally reserved for short-term use only.

In the past few years, clinical trials of Janus kinase inhibitors (baricitinib, ruxolitinib and tofacitinib) have shown promising results for alopecia areata.21-23 In 2023, baricitinib was approved by the TGA for the treatment of severe alopecia areata in adults who have failed or are not appropriate for other treatments; however, it is not listed on the PBS.24 Ruxolitinib and tofacitinib are not currently approved for the treatment of alopecia areata in Australia.

Patients should be warned that alopecia areata follows an unpredictable disease course and that there may be spontaneous periods of hair regrowth and recovery followed by relapse. The condition can have a significant emotional and psychological impact, and psychosocial support and counselling may be warranted.25 It may also be helpful to discuss camouflaging techniques, such as the use of wigs and hairpieces.19

Outcome

The case patient was diagnosed with alopecia areata that was moderate to severe and having a substantial psychological impact. She was informed that there is no cure for the disease and that the responses to treatment are variable. She was treated with intralesional corticosteroid injections, repeated four to six weekly, but her response was limited.

The patient was subsequently referred to a dermatologist, who commenced treatment with methotrexate 10 mg weekly with folic acid supplementation, but after six months her hair growth was insufficient. She then commenced treatment with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (off-label), which resulted in excellent hair regrowth within a six-month period (Figure 3). MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 70: 670-678.

2. Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: an update on pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2019; 20: 379-390.

3. Melo DF, de Mattos Barreto T, de Souza Albernaz E, de Carvalho Haddad N, Tortelly VD. Ten clinical clues for the diagnosis of frontal fibrosing alopecia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2019; 85: 559-564.

4. Gálvez‐Canseco A, Sperling L. Lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia cannot be differentiated by histopathology. J Cutan Pathol 2018; 45: 313-317.

5. Shannon F, Christa S, Lewei D, Carolyn G. Demographics of women with female pattern hair loss and the effectiveness of spironolactone therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 73: 705-706.

6. Küster W, Happle R. The inheritance of common baldness: two B or not two B? J Am Acad Dermatol 1984; 11(5 Pt 1): 921-926.

7. Chan L, Cook DK. Female pattern hair loss. Aust J Gen Pract 2018; 47: 459-464.

8. De Lacharrière O, Deloche C, Misciali C, et al. Hair diameter diversity: a clinical sign reflecting the follicle miniaturization. Arch Dermatol 2001; 137: 641-646.

9. Hautmann G, Hercogova J, Lotti T. Trichotillomania. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 46: 807-821.

10. França K, Kumar A, Castillo D, et al. Trichotillomania (hair pulling disorder): clinical characteristics, psychosocial aspects, treatment approaches, and ethical considerations. Dermatol Ther 2019; 32: e12622.

11. Kaczorowska A, Rudnicka L, Stefanato CM, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of trichoscopy in trichotillomania: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol 2021; 101: adv00565.

12. Simakou T, Butcher JP, Reid S, Henriquez FL. Alopecia areata: a multifactorial autoimmune condition. J Autoimmun 2019; 98: 74-85.

13. Kakourou T, Karachristou K, Chrousos G. A case series of alopecia areata in children: impact of personal and family history of stress and autoimmunity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007; 21: 356-359.

14. Chu S-Y, Chen Y-J, Tseng W-C, et al. Comorbidity profiles among patients with alopecia areata: the importance of onset age, a nationwide population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65: 949-956.

15. Waśkiel A, Rakowska A, Sikora M, Olszewska M, Rudnicka L. Trichoscopy of alopecia areata: an update. J Dermatol 2018; 45: 692-700.

16. Pratt CH, King LE, Messenger AG, Christiano AM, Sundberg JP. Alopecia areata. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017; 3: 17011.

17. Chelidze K, Lipner SR. Nail changes in alopecia areata: an update and review. Int J Dermatol 2018; 57: 776-783.

18. Stefanato CM. Histopathology of alopecia: a clinicopathological approach to diagnosis. Histopathology 2010; 56: 24-38.

19. Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, et al. Alopecia areata: an appraisal of new treatment approaches and overview of current therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78: 15-24.

20. Chartaux E, Joly P. Long-term follow-up of the efficacy of methotrexate alone or in combination with low doses of oral corticosteroids in the treatment of alopecia areata totalis or universalis. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2010: 137: 507-513.

21. Jabbari A, Dai Z, Xing L, et al. Reversal of alopecia areata following treatment with the JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib. EBioMedicine 2015; 2: 351-355.

22. Mackay-Wiggan J, Jabbari A, Nguyen N, et al. Oral ruxolitinib induces hair regrowth in patients with moderate-to-severe alopecia areata. JCI Insight 2016; 1: e89790.

23. Guo L, Feng S, Sun B, Jiang X, Liu Y. Benefit and risk profile of tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata: a systemic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: 192-201.

24. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Olumiant (Eli Lilly Australia Pty Ltd). Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/prescription-medicines-registrations/olumiant-eli-lilly-australia-pty-ltd-1 (accessed October 2024).

25. Güleç AT, Tanrıverdi N, Dürü Ç, Saray Y, Akçalı C. The role of psychological factors in alopecia areata and the impact of the disease on the quality of life. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43: 352-356.