What’s the diagnosis?

A woman with red papules on the eyelids

Case presentation

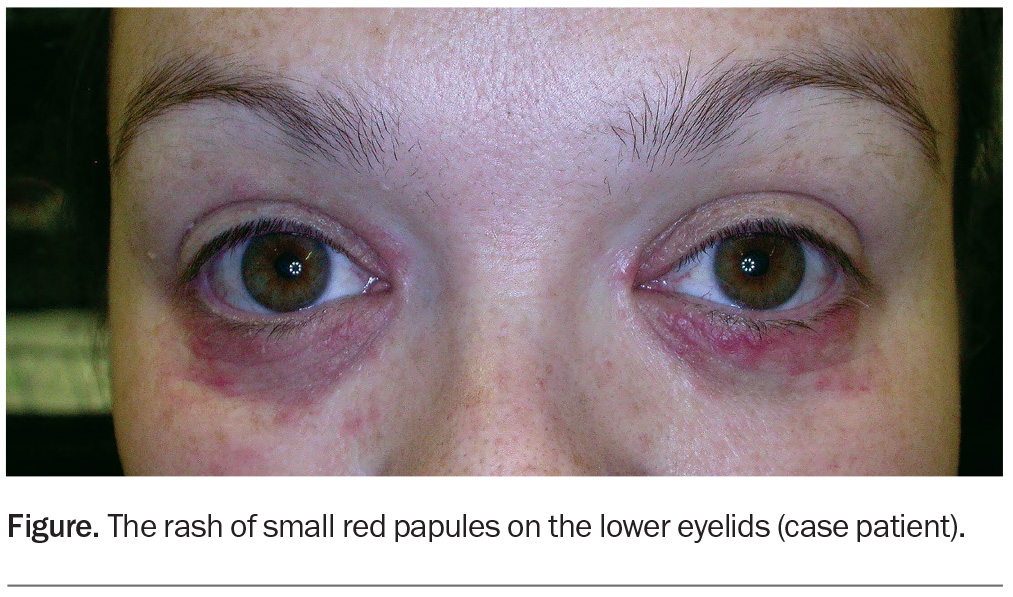

A 37-year-old woman presents with a six-month history of small red papules on her lower eyelids (Figure). The papules are sensitive and occasionally painful but not itchy. She was prescribed hydrocortisone 1% ointment, which she used intermittently for three months. There was initial improvement, but the lesions became resistant to treatment. She was then prescribed methylprednisolone aceponate 0.1% cream once daily. There was initial improvement, but subsequent recurrence occurred, followed by worsening of the eyelid rash.

The patient is otherwise well. She uses minimal make-up, washes with a soap-free cleanser and uses a bland emollient on her face. She works in an office and is not exposed to dust or other obvious irritants. She uses an etonogestrel implant for contraception.

On examination, multiple, small, erythematous papules are noted on the lower eyelids, with some in close proximity to the medial canthi bilaterally. There is sparing of the upper eyelids.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis, one of the most common inflammatory dermatoses in Australia, is orchestrated by an interplay of factors, including skin barrier disruption and immune dysregulation, as well as an underlying genetic predisposition. Atopic dermatitis typically presents early in life and may occur with features of the ‘atopic march’, where patients report associated food allergies, allergic rhinitis and asthma.1

Atopic dermatitis can present as intensely itchy, eczematous, exudative lesions with papulopustulation and fissuring around the eyes. There may be a background of xerosis and lichenification, typically in flexural areas. Although it affects all age groups, eyelid atopic dermatitis is more commonly noted among adolescents than adults or children.2

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. She did not have a history of atopy and her eyelid rash was not itchy.

Allergic and irritant contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common cause of eyelid dermatitis.3 Type IV hypersensitivity reactions to nickel(II) sulfate in cosmetics used around the eyes (e.g. mascara, eye shadow) and contact lens cleaning solutions can trigger periocular allergic contact dermatitis.4 Fragrances and preservatives (e.g. thiomersal) in cosmetics have also been reported to cause the condition, and the use of products that are free of fragrances and preservatives should be recommended to all patients who present with eyelid dermatitis.1,4 Hypersensitivity reactions to antibiotics (e.g. neomycin) can also result in allergic contact dermatitis.4

Inflammatory dermatoses around the eye can also be caused by direct contact with irritants, including ingredients in cosmetic products. Airborne particles such as dusts and vapours (such as perfumes) can also cause contact dermatitis. A history of exposure to an irritant and clinical improvement after avoidance is highly suggestive of the diagnosis.4

Contact dermatitis, which can present as an eczematous rash, was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, who denied the use of cosmetics or exposure to other irritants around her eyelids.

Ocular rosacea

Patients with ocular rosacea commonly present with blepharitis, conjunctival hyperaemia and rosacea-associated keratitis.5 Coexisting skin features of rosacea may be noted, such as mid-facial flushing, prominent vasculature and papulopustulation. The aetiology is thought to be driven by a complex interplay among immunological factors, the skin microbiome and extracellular matrix. There are many triggers, including spicy food and alcohol.2

Demodex mites, which have been implicated in the pathogenesis of rosacea, can also cause folliculitis, resulting in widespread facial papules and pustules leading to periocular dermatitis.6 Results of skin biopsies have shown an increased demodex load to be associated with several inflammatory skin conditions, and objective evaluation of demodex load is not routinely used in clinical practice.5,7

The case patient did not report a history of facial flushing and her eyelid rash was not exacerbated by common rosacea triggers. Furthermore, no blepharitis, conjunctival hyperaemia or rosacea-associated keratitis was evident on examination.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is a common skin condition that affects areas that are rich in sebaceous glands, such as the face, scalp, trunk and intertriginous areas. It typically involves colonisation by Malassezia, commensal yeasts that cleave fatty acids within sebum and which is presumed to trigger inflammatory dermatoses in susceptible individuals.8,9 It is more common in adults and may affect only the eyelid margins.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis presents as greasy, erythematous patches with yellow/white scale. It has a predilection for the scalp and facial ‘T zone’, with affected skin of the eyebrow and eyelid area leading to periocular dermatitis.8,9

Seborrhoeic dermatitis was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, whose rash was localised to the eyelid area and did not have greasy scale on examination.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus, which is caused by the reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus, is characterised by a unilateral painful skin rash in one or more dermatomal distributions of the trigeminal nerve. The lesions can present as erythematous macules, papules and vesicles over the eyelids. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus requires prompt treatment to prevent loss of vision and is an ophthalmic emergency.10

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, whose eyelid involvement was bilateral and did not have a dermatomal distribution.

Periocular dermatitis

This is the correct diagnosis. Periocular dermatitis is characterised by erythematous papules in close proximity to the eyes. It can coexist with perinasal and perioral dermatitis (periorificial dermatitis) or occur in localised form. It is most commonly seen in women between 16 and 45 years of age.3 The clinical diagnosis of periocular dermatitis can be challenging due to overlapping features with several common conditions, as discussed above. It can be a chronic relapsing disease.

The cause of periocular (or periorificial) dermatitis is not well understood. Several triggers have been identified, including long-term application of corticosteroids – particularly potent topical corticosteroids, which should be avoided on the face and eyelids.11 Use of cosmetics can also trigger periocular dermatitis. Histologically, it is associated with a perivascular and perifollicular mononuclear cell infiltrate with eczematous and granulomatous changes.4

Management

Initial management of periocular dermatitis involves avoidance of triggers and irritants that can cause occlusion, such as cosmetics. The use of any topical corticosteroids must be ceased, with a gradual tapering sometimes recommended to avoid a rebound flare, and further use of topical corticosteroids should be avoided.9 General skincare measures, such as regular use of a soap-free cleanser and simple emollient, should be recommended. Patients should be advised to minimise sun exposure and to use a low-irritant sunscreen.

Calcineurin inhibitors are effective nonsteroidal immunomodulatory therapies for reducing inflammation. For mild cases of periocular dermatitis, topical pimecrolimus 1% cream can be used as a first-line treatment.12

Second-line options involve oral antibiotics, which are used for their anti-inflammatory benefits and when microbial superinfection is suspected to be an exacerbating factor.11 These include tetracycline antibiotics, such as doxycycline 50 to 100 mg daily for four to eight weeks, or erythromycin 250 to 500 mg daily for four to eight weeks when tetracyclines are contraindicated.13,14

For severe cases, oral isotretinoin can be prescribed by a dermatologist. Low doses of isotretinoin can be used; the usual initial dose is 0.2 mg/kg, which is tapered as clinical improvement is achieved.15 Common adverse effects include headaches, dry skin and mucous membranes, and gastrointestinal upset.16 Isotretinoin is a potent teratogen.

Outcome

The case patient was diagnosed with periocular dermatitis. She was advised to cease use of topical corticosteroids and was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg daily. She was given information about general skincare measures and advised to continue using her bland emollient. She experienced a brief flare of her periocular dermatitis, which is commonly seen after stopping topical corticosteroid therapy, and settled after two to three weeks. The rash then gradually improved. Complete clearance was achieved after about six weeks and the antibiotic therapy was stopped. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Feser A, Plaza T, Vogelgsang L, Mahler V. Periorbital dermatitis – a recalcitrant disease: causes and differential diagnoses. Br J Dermatol 2008; 159: 858-863.

2. Ricci G, Bellini F, Dondi A, Patrizi A, Pession A. Atopic dermatitis in adolescence. Dermatol Reports 2012; 4: e1.

3. Nethercott JR, Nield G, Holness DL. A review of 79 cases of eyelid dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989; 21(2 Pt 1): 223-230.

4. Feser A, Mahler V. Periorbital dermatitis: causes, differential diagnoses and therapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2010; 8: 159-166.

5. Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, Hata TR. Rosacea: part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 72: 749-758.

6. Gray NA, Tod B, Rohwer A, Fincham L, Visser WI, McCaul M. Pharmacological interventions for periorificial (perioral) dermatitis in children and adults: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36: 380-390.

7. Dolenc-Voljc M, Pohar M, Lunder T. Density of Demodex folliculorum in perioral dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol 2005; 85: 211-215.

8. Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician 2015; 91: 185-190.

9. Lipozenčić J, Ljubojević S. Perioral dermatitis. Clin Dermatol 2011; 29: 157-161.

10. Cohen EJ, Jeng BH. Herpes zoster: a brief definitive review. Cornea 2021; 40: 943-949.

11. Lipozenčić J, Hadžavdić SL. Perioral dermatitis. Clin Dermatol 2014; 32: 125-130.

12. Schwarz T, Kreiselmaier I, Bieber T, et al. A randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study of 1% pimecrolimus cream in adult patients with perioral dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59: 34-40.

13. Choi yL, Lee KJ, Cho HJ, et al. Case of childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis in a Korean boy treated by oral erythromycin. J Dermatol 2006; 33: 806-808.

14. Ellis CN, Stawiski MA. The treatment of perioral dermatitis, acne rosacea, and seborrheic dermatitis. Med Clin North Am 1982; 66: 819-830.

15. Smith KW. Perioral dermatitis with histopathologic features of granulomatous rosacea: successful treatment with isotretinoin. Cutis 1990; 46: 413-415.

16. James WD. Acne. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 1463-1472.