What’s the diagnosis?

A woman with rosy cheeks and erythematous facial lesions

Case presentation

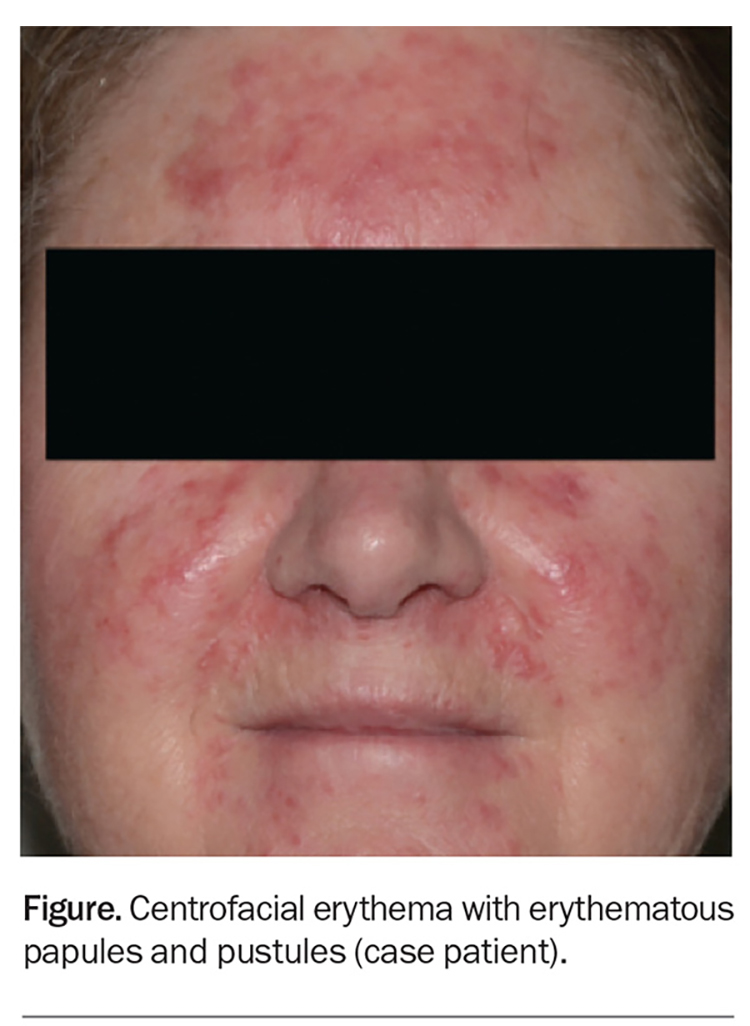

A 57-year-old woman presents with a history of several months’ duration of erythematous papules and pustules on her face with associated skin sensitivity and a stinging sensation. She reports frequent facial flushing, particularly with exercise or after ingestion of spicy foods, tea, coffee and alcohol. She does not have any medical history of note and does not take any regular medications.

On examination, background erythema and erythematous papules and pustules are observed to be affecting the central portion of the patient’s face, including her forehead, cheeks, chin and infranasal region (Figure).

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Acne vulgaris

Acne vulgaris, an inflammatory disorder of the pilosebaceous unit, is one of the most common skin conditions, affecting about 85% of adolescents and 9.4% of the global population.1,2 The pathogenesis involves a complex interplay between increased sebum production and follicular hyperkeratinisation, which results in comedone formation and subsequent proliferation of Cutibacterium acnes (formerly Propionibacterium acnes) and inflammation. Well-known predisposing factors include family history, androgen excess, insulin resistance and psychological stress.3-5 There is limited evidence about the role of diet, but some studies have demonstrated an association between acne and dairy or foods with a high glycaemic load.5-8

Acne has a predilection for body sites that have a high concentration of sebaceous glands, such as the face, upper back and chest. The condition is characterised by comedones, both open (blackheads) and closed (whiteheads), as well as erythematous and inflamed papules, pustules, cysts and nodules. There may also be postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring (atrophic, boxcar, ice pick, rolling, hypertrophic and keloid).

For the case patient, no comedones are observed on examination. The lesions are concentrated in the central portion of the face, whereas the lesions of acne vulgaris would be expected to be more widespread. Acne is not usually associated with facial flushing.

Folliculitis

Folliculitis (inflammation of the hair

follicle) can be infectious or noninfectious. Infectious folliculitis is commonly caused by bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus spp., Gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa) but can also be brought about by fungi (dermatophytes, Malassezia spp. [discussed below], Candida spp.), viruses (herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus) and parasites (Demodex spp.). Hair removal (shaving, waxing, epilating, plucking) can inflame the hair follicles during the removal process, increasing the risk of folliculitis. Other causes of noninfectious folliculitis include irritants (e.g. cutting oils, tar products, other chemicals), occlusion (e.g. by oils, ointments, adhesives) and drugs (e.g. corticosteroids, androgens) as well as immunosuppression (eosinophilic folliculitis in the setting of HIV infection) and inflammatory skin diseases (e.g. folliculitis decalvans). A swab can be taken for microscopy and culture to distinguish between infectious and noninfectious types of folliculitis.

Folliculitis affects body sites with hair. The condition is characterised by tender follicular papules or pustules on an erythematous base. Follicular lesions can be distinguished from their nonfollicular counterparts by the presence of hair piercing the lesions and spatial pattern, which follow the hair follicle distribution.

For the case patient, the erythema is more widespread than perifollicular and the papules and pustules do not have a folliculocentric distribution. Folliculitis is not associated with facial flushing.

Pityrosporum folliculitis

The pathogenesis of pityrosporum folliculitis (also known as Malassezia folliculitis) involves follicular occlusion followed by overgrowth of Malassezia in a sebaceous environment. Living in a hot, humid climate has been reported as a predisposing factor.9,10 As Malassezia is part of normal skin flora in 90% of individuals, it has been postulated that altered host immunity and immunosuppression may play a role.11,12 The incidence has been observed to be higher after antibiotic use.13

Pityrosporum folliculitis manifests as small, pruritic, monomorphic, folliculocentric papules and pustules on the upper back and chest. Other sites, such as the forehead, hair line and chin, can also be affected, albeit not as often.

Dermoscopic findings include perifollicular erythema, perilesional scales, and hair that is hypopigmented and coiled or looped.14 Woods lamp examination may show a yellow-green fluorescence. A potassium hydroxide test performed on skin scrapings may show budding yeasts.

For the case patient, the lesions are not pruritic, folliculocentric or monomorphic. There is no associated flushing in pityrosporum folliculitis.

Rosacea

This is the correct diagnosis. Rosacea, a chronic inflammatory dermatosis with centrofacial distribution, has a predilection for women aged between 30 and 50 years, particularly those of Celtic and northern European descent and skin phototype I or II.15 However, men, darker-skinned individuals and other age groups can also be affected. The global prevalence is estimated to be 5.5%.16

The exact pathogenesis of rosacea is unknown but multiple factors are thought to be contributory, including a genetic predisposition and immune and neurocutaneous dysregulation in response to internal and external triggers, which lead to hyperinflammation and the resultant characteristics of rosacea.17 Common triggers include exposure to ultraviolet radiation, spicy foods, hot beverages, exercise, alcohol, temperature change and psychological stress.18

Rosacea has been associated with systemic diseases, including cardiovascular, respiratory and metabolic disorders, neurological diseases (such as Parkinson’s disease) and autoimmune disorders (such as rheumatoid arthritis, coeliac disease and multiple sclerosis).18,19 Further studies are needed to confirm these associations.

Diagnosis

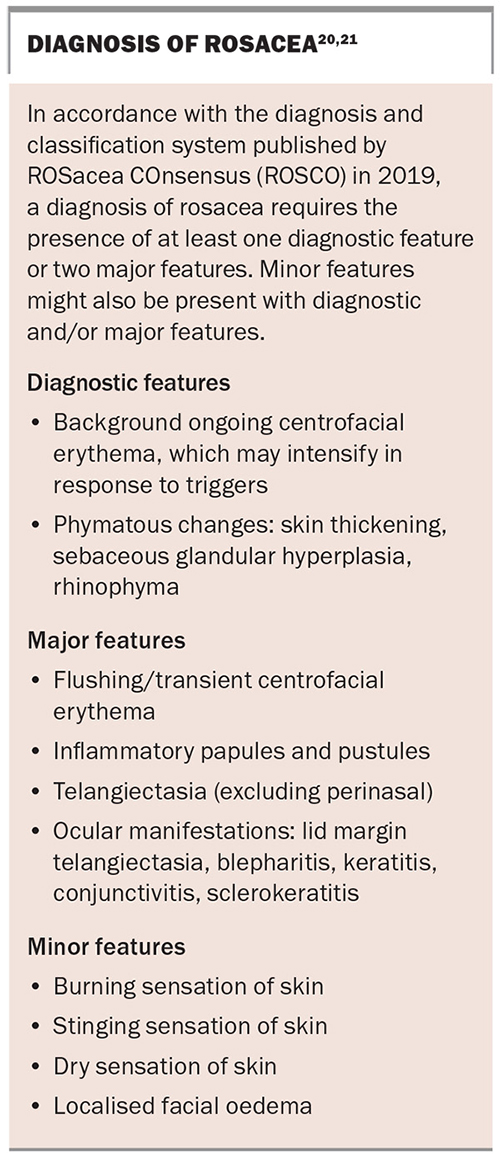

The diagnosis of rosacea can pose a challenge because the condition shares many common features with other facial dermatoses that may be present concurrently, such as those listed above. Traditionally, rosacea was divided into four subtypes: erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous and ocular. However, the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel recently created a new diagnostic and classification system (see Box), to reduce the subtype overlaps frequently seen in clinical practice.20,21 The case patient fulfils the diagnostic requirement for rosacea with background ongoing centrofacial erythema (diagnostic feature), and the intensification by known triggers further supports the diagnosis. She also has centrofacial flushing, inflammatory papules and pustules (two major features) and a stinging sensation of the skin (minor feature).

Management

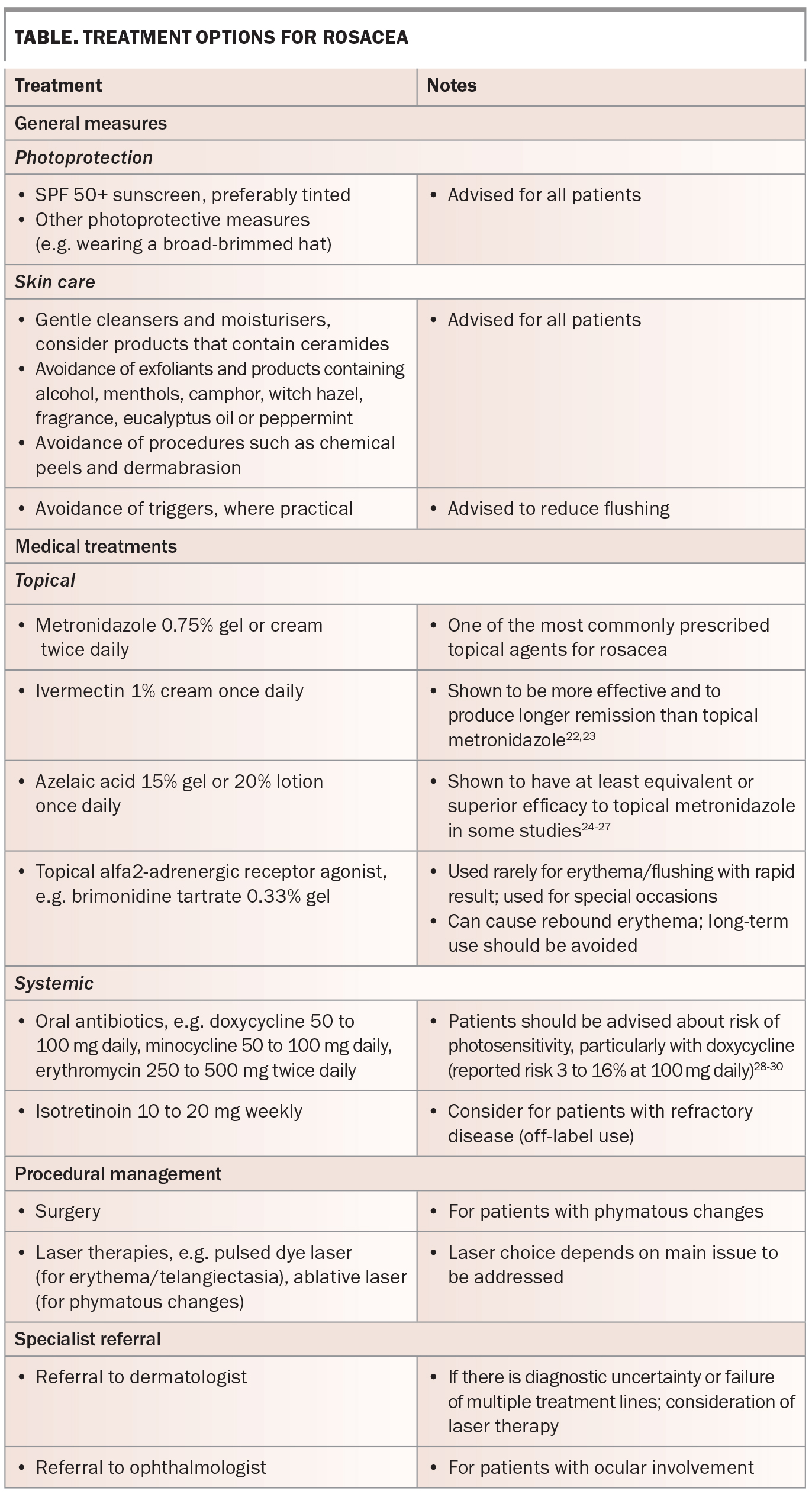

Current treatment options for rosacea are outlined in the Table.22-30 Management requires a holistic approach, and should be individualised according to the main presenting features. The condition is not curable, but it can ‘burn out’ after several years. It is important that patients are educated about the chronicity of rosacea and its remitting/relapsing nature.

Outcome

The case patient was reviewed by a dermatologist and diagnosed with rosacea. She was advised about the chronicity of the disease and the importance of general skincare measures, photoprotection and trigger avoidance. She had previously tried topical metronidazole cream for a few months with no improvement in her symptoms. Therefore, she was commenced on oral doxycycline 100 mg daily. At one month follow-up, her facial eruption was almost completely cleared. To maintain remission, the doxycycline dosage was reduced to 100 mg every two days, and then further reduced to three times a week. It should be noted that the aim was to reduce the dose of doxycycline to the lowest possible dose that maintains remission (e.g. 50 mg three times a week) but this can vary between patients. In the presented case, the patient developed gastrointestinal discomfort with doxycycline after some time, and her maintenance treatment was changed to low-dose isotretinoin 20 mg twice a week, which has maintained disease remission and been well tolerated. MT

References

1. Tan JKL, Bhate K. A global perspective on the epidemiology of acne. Br J Dermatol 2015; 172 Suppl 1: 3-12.

2. Lynn DD, Umari T, Dunnick CA, Dellavalle RP. The epidemiology of acne vulgaris in late adolescence. Adolesc Health Med Ther 2016; 7: 13-25.

3. Yosipovitch G, Tang M, Dawn AG, et al. Study of psychological stress, sebum production and acne vulgaris in adolescents. Acta Derm Venereol 2007; 87: 135-139.

4. Nagpal M, De D, Handa S, Pal A, Sachdeva N. Insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in young men with acne. JAMA Dermatol 2016; 152: 399-404.

5. Di Landro A, Cazzaniga S, Parazzini F, et al. Family history, body mass index, selected dietary factors, menstrual history, and risk of moderate to severe acne in adolescents and young adults. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67: 1129-1135.

6. Fabbrocini G, Izzo R, Faggiano A, et al. Low glycaemic diet and metformin therapy: a new approach in male subjects with acne resistant to common treatments. Clin Exp Dermatol 2016; 41: 38-42.

7. Smith RN, Mann NJ, Braue A, Mäkeläinen H, Varigos GA. The effect of a high-protein, low glycemic-load diet versus a conventional, high glycemic-load diet on biochemical parameters associated with acne vulgaris: a randomized, investigator-masked, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57: 247-256.

8. Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Danby FW, Frazier AL, Willett WC, Holmes MD. High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52: 207-214.

9. Durdu M, Guran M, Ilkit M. Epidemiological characteristics of Malassezia folliculitis and use of the May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain to diagnose the infection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 76: 450-457.

10. Suzuki C, Hase M, Shimoyama H, Sei Y. Treatment outcomes for Malassezia folliculitis in the dermatology department of a university hospital in Japan. Med Mycol J 2016; 57: E63-E66.

11. Faergemann J, Johansson S, Bäck O, Scheynius A. An immunologic and cultural study of pityrosporum folliculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 14: 429-433.

12. Roberts SOB. Pityrosporum orbiculare: incidence and distribution on clinically normal skin. Br J Dermatol 1969; 81: 264-269.

13. Prindaville B, Belazarian L, Levin NA, Wiss K. Pityrosporum folliculitis: a retrospective review of 110 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78: 511-514.

14. Jakhar D, Kaur I, Chaudhary R. Dermoscopy of pityrosporum folliculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: e43-e44.

15. Elewski BE, Draelos Z, Dréno B, Jansen T, Layton A, Picardo M. Rosacea – global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011; 25: 188-200.

16. Gether L, Overgaard LK, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP. Incidence and prevalence of rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 2018; 179: 282-289.

17. van Zuuren EJ, Arents BWM, van der Linden MMD, Vermeulen S, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J. Rosacea: new concepts in classification and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2021; 22: 457-465.

18. van Zuuren EJ. Rosacea. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1754-1764.

19. Egeberg A, Hansen PR, Gislason GH, Thyssen JP. Clustering of autoimmune diseases in patients with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74: 667-672e1.

20. Tan J, Almeida LM, Bewley A, et al. Updating the diagnosis, classification and assessment of rosacea: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 431-438.

21. Schaller M, Almeida LMC, Bewley A, et al. Recommendations for rosacea diagnosis, classification and management: update from the global ROSacea COnsensus 2019 panel. Br J Dermatol 2020; 182: 1269-1276.

22. Taieb A, Ortonne JP, Ruzicka T, et al; Ivermectin Phase III study group. Superiority of ivermectin 1% cream over metronidazole 0.75% cream in treating inflammatory lesions of rosacea: a randomized, investigator-blinded trial. Br J Dermatol 2015; 172: 1103-1110.

23. Taieb A, Khemis A, Ruzicka T, et al. Maintenance of remission following successful treatment of papulopustular rosacea with ivermectin 1% cream vs. metronidazole 0.75% cream: 36-week extension of the ATTRACT randomized study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016; 30: 829-836.

24. Maddin S. A comparison of topical azelaic acid 20% cream and topical metronidazole 0.75% cream in the treatment of patients with papulopustular rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999; 40(6 Pt 1): 961-965.

25. Wolf JE Jr, Kerrouche N, Arsonnaud S. Efficacy and safety of once-daily metronidazole 1% gel compared with twice-daily azelaic acid 15% gel in the treatment of rosacea. Cutis 2006; 77(4 Suppl): 3-11.

26. Elewski BE, Fleischer AB Jr, Pariser DM. A comparison of 15% azelaic acid gel and 0.75% metronidazole gel in the topical treatment of papulopustular rosacea: results of a randomized trial. Arch Dermatol 2003; 139: 1444-1450.

27. Mostafa FF, El Harras MA, Gomaa SM, Al Mokadem S, Nassar AA, Abdel Gawad EH. Comparative study of some treatment modalities of rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009; 23: 22-28.

28. Layton AM, Cunliffe WJ. Phototoxic eruptions due to doxycycline – a dose-related phenomenon. Clin Exp Dermatol 1993; 18: 425-427.

29. Lim DS, Murphy GM. High-level ultraviolet A photoprotection is needed to prevent doxycycline phototoxicity: lessons learned in East Timor. Br J Dermatol 2003; 149: 213-214.

30. Goetze S, Hiernickel C, Elsner P. Phototoxicity of doxycycline: a systematic review on clinical manifestations, frequency, cofactors, and prevention. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2017; 30: 76-80.