The future of medicine: will we be crushed by elephants?

Dr Ellard, revered former Editor of Modern Medicine of Australia and later, Medicine Today, and a distinguished psychiatrist, wrote many essays between the 1970s and early 2000s on society’s most controversial and vexing issues. These were published in various journals including Modern Medicine of Australia and Medicine Today, and some were also compiled and published as books. This essay ‘The future of medicine: will we be crushed by elephants?’ originally appeared in the April 2000 issue of Medicine Today. It still resonates today.

This Viewpoint is longer than an article should be, but the topic – your future and mine – is so centrally important to the medical community and to the whole country that I have breached my own standards.

To look into the future is difficult. One is thoroughly entangled in the present, and this keeps getting in the way, limiting one’s view. It is easy to think that things will change little and that one can keep on doing the same old things in the same old way – and get away with it.

For example, I remember many years ago reading an article in Scientific American by some researchers who had managed to get a piece of silicon to perform mathematical calculations. I could think of nothing more absurd than expecting silicon – the stuff one sees on a beach – to do mathematics. I moved on to the next article, passing over such an absurdity.

Wondering how to escape from that intellectual cage, I hit upon a device. I imagined that I was the occupant of a flying saucer, sent here from a galaxy far away, to report on our species for a particular reason. My report, to the Board of the Alpha Centauri Intergalactic Maintenance Company, follows.

Project Earth: mission ‘wise man’

As instructed I have spent two Earth years examining the planet Earth generally and with particular reference to the creatures at the top of the food chain. My report covers two aspects: when the creatures are programmed correctly and when they are programmed incorrectly.

Correct programming

Let us begin with the technique for producing new creatures. I have not seen the like of it on any other planet that I have surveyed. First, two adult creatures go to a secluded place and rub themselves together in a curious way. For some unknown reason, there is generally a rush towards the end of the procedure. Occasionally, but by no means usually, this activity results in the formation of one or more small new creatures inside one of the old ones.

The problem is obvious: the new creature grows and in due course must escape into the outside world. This process may be trouble free, but sometimes it goes wrong and the new creature gets stuck on the way out. Freeing it can be complicated and quite expensive. It may even mean making a large incision in the host creature, extracting the new one and then sewing up the old one.

With your Company’s project in mind, I found this observation disheartening but worse was to follow. Let us consider correctly programmed creatures in a favourable environment. Generally, all goes well for a few Earth decades and then obvious signs of degeneration appear. Their visual apparatus begins to deteriorate and they need lenses to see things properly. Their hearing loses some of its sensitivity and their central processing unit becomes slower, more prone to error and loses some of its memory. Their locomotor system weakens and some of them appear to find it painful and difficult to get about.

To put it shortly, they have obsolescence built into them, appearing at the end of a small number of Earth decades. They need increasing amounts of maintenance and repair.

After eight or nine decades, almost all of them have failed completely and have to be burnt or buried.

Incorrect programming

It is much worse when, as is often the case, these creatures are programmed incorrectly. Not long after they are activated, they develop one or more problems in their systems.

For example, they have a liquid internal transport system that carries oxygen to the various parts of their hardware. It may operate at too high a pressure or the tubes in which the transport fluid flows may rupture or become thickened and block up. The apparatus, which extracts oxygen from their atmosphere, is prone to disorder; the prevalence of this problem is increasing.

The list of problems is endless. By the end of the fifth Earth decade, most of them are on some sort of chemical supplement to improve their functioning. Some need painful, expensive and complex modifications of their hardware – they call this surgery.

Another problem in their design is that they must be emptied and refuelled at very short intervals. If they are fuelled excessively, they swell up and their internal processes degenerate. If they are refuelled inadequately, they lose mass and disintegrate. If they are not emptied, catastrophes occur.

Self-destructive behaviour

You would think that with all these difficulties facing them these creatures would devote most of their ingenuity and resources to solving their problems. Not a bit of it.

Consider this. They form themselves into tribes, the individuals drawn together by the location of their habitats, a similarity of beliefs or a common envy of the possessions of other tribes, or for some other equally absurd reason. Having done this, they kill each other by the millions while proclaiming the superiority of their own morals and motives. A substantial amount of the scientific progress they have made since their ancestors came down from the trees has arisen from the search for better ways of killing their fellow creatures.

At the individual level, it is much the same. There is much talk of family values and of the importance of the family. Their statistics show that if a creature is murdered it is much more likely that its murderer will be a member of its family than a passing stranger. Their capacity for ignoring the obvious is remarkable.

They destroy themselves in other ways. They are fond of a fluid called alcohol which, when taken to excess, destroys their central processing unit. Again, they grow a weed, roll it into cylinders, put one end of the cylinder in their mouths, set fire to the other and then inhale the smoke. This kills them by the millions.

One more example of the self-destructive behaviour of these creatures will suffice. Since their locomotion is slow they have devised machines that get them around much faster. The problem is that many of them conduct these machines recklessly and incompetently, and huge numbers are killed and maimed in this way.

Some cautionary words

Before making my recommendation to the Board, I must mention two things:

The first issue is their composition. Incredible as it may seem, these creatures are made of a mineral containing calcium (called bone) and meat. The central processing unit, which sits in a bony container on top of their bodies, is made of meat. It is amazing that it works at all, but clearly one cannot expect too much of it. Certainly the owners of these meat processors have very little insight into its limitations. Their name for themselves, chosen from one of their old languages, is Homo sapiens (wise man). Recently, the term Homo sapiens sapiens has appeared – very wise man. No comment is necessary.

The second issue is what they have done to resolve their own maintenance problems. For most of their history there was little that they could do. Therefore, in one sense, all possible solutions were simple. For example, if one of them fell over and could not get up because its leg was bent, they worked out that if they pulled the leg straight, tied it to a straight stick and waited, sometimes it would work again.

For anything more complicated than this they went to a holy man, who jumped up and down, waved his arms and chanted spells. It did not do much good, it did little harm, everyone felt a bit better and the cost was negligible.

As I have said, they began to move from their state of total savagery to a primitive state a few hundred years ago. What they call scientific medicine is not much more than 100 Earth years old.

This does not mean their faith in magic is any less. They still spend vast sums of money on substances that have not been shown to have any beneficial effect over a placebo. In addition to magic, the creatures use organised inefficiency. They are organised and regulated by what they call governments. Governments are assemblages of creatures characterised by a need to acquire and cling to what they perceive to be power. Above all, they must refrain from doing anything that they believe will upset the general populace and lose them votes.

Surrounded by disease and decay, what do they talk about? Health – that is, the absence of disease. Not only this, but in a peculiar way they talk about health as if it were a substance. Thus creatures do not get treated for disease, they consume health. Whether they are supposed to consume it with knives and forks or chopsticks is not clear. You can see where having a central processing unit made of meat can get you.

The immediate crisis

Their more advanced – that is, less primitive – countries are now in a state of crisis. Communications have improved and the ordinary creature can see that to keep itself going until the end of its programmed obsolescence will require much effort and expenditure of resources. Furthermore, its expectation is that the effort and expenditure will be provided by someone else, while it does little more than complain if it does not receive a perfect result and perhaps live forever.

To make the crisis more pressing, in countries with better technology and communications, the average age of the creatures is advancing so that they require more maintenance per unit. The technology involved for both diagnosis and treatment becomes increasingly more expensive. Everyone expects total medical care and that someone else will pay for it.

The bottom line is that there never has been, is not now and never will be enough resources to provide that happy state of affairs. Some will miss out – there is no escape from this problem.

Their leaders will never come out in the open and say it, because it would certainly harm their own popularity and lead to a loss of votes, with a consequent loss of what they perceive to be power. They dither about, producing high sounding but flatulent strategic plans, targets and the like, but the situation is intractable.

My firm recommendation to your Board is that the Company should not in any circumstance tender for the maintenance of these creatures on planet Earth. They should be left to work it out themselves. Better still, one of our commercial opponents may decide to do it, and bankrupt itself.

Back to us

If the aliens cannot rescue us, then we must do our best ourselves.

Before discussing how, a note of caution about prediction. Some years ago, a Canadian study tried to predict the number of teachers, nurses, etc. that would be needed in the future. It emerged that the absolute limit of prediction under the best of circumstances was about 10 years – to try to look further into the future would require necromancy.

Can logic and reason be used to solve the problem? At present, health care is distributed by lottery. If you happen to live in the right area, have the necessary amount of money and know where the best care is to be found then you are likely to live longer and more comfortably than the rest of the population.

Can we do better? While health care will always be rationed, might there not be a better basis upon which it could be apportioned? The US state of Oregon decided to do that: the relevant Act was passed in 1994. We have much to learn from what happened.

The first problem was to decide the particular medical services that the state of Oregon should subsidise, it being agreed that the state could not subsidise everything. The second problem was to rank those things in order of benefit, and the third to decide where the cutoff point had to be placed. Services above the line would be funded; those beneath it would not.

Decision makers included 54 panels of doctors, a telephone survey of 1000 citizens and 47 public meetings, involving more than a 1000 people. They produced a draft priority list of 1600 services in May 1990. Cost effectiveness was paramount. For example, treatment for thumb sucking was ranked higher than hospitalisation for a starving child.

The citizens’ committees were supposed to represent the general population; however, 56% were healthcare workers and fewer than 10% were below the federal poverty line (the main target group). Not only were those making decisions a skewed group, but also the data upon which the decisions were made were decidedly rubbery. When the list was produced, it was inspected and some items were moved up and others down ‘by hand’ on unspecified criteria.1

It was a good try, and valuable. It showed how difficult it is to produce a list of specific medical services that can then be ranked in terms of their desirability, particularly as desirability could be seen very differently by the various community groups. Even if such a list had been handed down from on high on 10 tablets of stone, it would soon be out of date. Think of the changes that have occurred in the treatment of peptic ulcerations in the last decade or two.

Note also that even if we all agree that the treatment of acute appendicitis should be on the list, there is the further problem of the level at which the service should be provided. What would be expected if a member of the International Olympic Committee were to have his or her appendix removed? What brand of champagne and caviar should be served postoperatively, etc?

And even when the tablets of stone were fresh and new, who would agree to pay for it all? A survey conducted in the West Australian found that only 35% of those polled were prepared to pay higher taxes to improve the public healthcare system.2

An unwanted task?

As implied in the report from the flying saucer, no rational body would wish to provide healthcare services to creatures like us. Who is in the running? Currently, government in its many manifestations has most of the responsibility. Clearly, it is a burden that governments would like to shed. While we have the extraordinary relationship between the USA and the Commonwealth, they can shuffle the burdens and outcomes between them. None of them enjoys it.

Making money

Once we had a government airline (QANTAS), a Commonwealth bank, a government insurance office, state-owned railways, etc. Gas and electricity have either been or are soon to be privatised everywhere. While not wishing to extol or discredit the process of privatisation, I wish to point out that it exists.

Now let us consider health. All or most of the Veterans hospitals are run by private organisations. In NSW, most of the large teaching hospitals have a private hospital closely associated with them. Some of the privately insured patients who used to contribute to the maintenance of the large hospitals now go to the private hospitals. How long do you think it will be before the government says to those running the private hospital: ‘You are doing a good job there; if you want to keep doing it, run the large one as well’?

If I am right and governments slowly wriggle out of health one way or the other, who will pick it up, and why? The only conceivable inducement is anticipated profit – if you can think of another one, let me know.

Can profits be made? Yes. Let me give you some figures from the ABC’s Health Care Report in 1995.3 Ralph Nader stated that the person in charge of US healthcare had a salary package and stock holding of US$783 million dollars. The person in charge of Ivax Corporation had an annual package of US$266 million but the one in charge of Humana could only rake together US$194 million.

In 1995, the corporations and stock options of the top 10 managers and chief executive officers totalled US$2.4 billion dollars.

You may say that these people earn these great sums because of the economies that they introduce. In the USA, hospitals that were highly involved in managed care in 1999 had a median administrative expense per patient of $1,400 – that is, 47% higher than the median expense for all US hospitals.4

Who can afford to even contemplate taking over health? In the commercial world, companies are fewer and bigger. It is expected that there will only be five major automobile manufacturers in the world soon; take overs continue. The same happens to banks, insurance companies and pharmaceutical companies. They become bigger and they have the most to gain.

…and losing it

Recent figures illustrate that running healthcare schemes is not as profitable as it was once thought to be. In January 1999, The New England Journal of Medicine reported that one of the largest and most respected health maintenance organisations (HMOs), Kaiser-Permanente, had a loss of US$270 million in 1997, its first deficit in more than 50 years of operations. It was thought that the 1998 loss would be greater. Another HMO, Oxford Health Plan, had a stockmarket share price of US$90 in early 1997. It had lost 70% of that value by the end of 1997.5

In September 1999, the same journal reported that at least five HMOs and one indemnity-insurance carrier closed operations or merged in Chicago during the second half of 1998.6 As a result, the fees for healthcare cover are increasing and many employers, who have been paying up to now, are shifting the burden to their employees. These employees are saying ‘no thank you’ and stopping their healthcare cover.

To add to the situation, many of the HMOs are heavily leveraged. If the Dow Jones goes down, some will be in trouble. Since almost half of all practising physicians in the USA are currently working as employees of organisations, the medical profession may encounter problems too.7

The prediction

Who then will have the resources and the incentive? I can see but one possibility – the pharmaceutical companies. Their mergers proceed at a pace that has left me confused. It is not difficult to see how those running them might have thought that a little guidance in the use of medications might be advantageous for their profits. The overall cost of prescription drugs continues to rise faster than the cost of the other components of healthcare. If one could control health and the particular medications being used, perhaps there is a profit to be made. Remember that in the USA, gag clauses prevented doctors from mentioning treatments other than those available under the plan that employs them.

Thus, the best prediction that I can make is that no matter what they say and promise, governments will ease themselves out of healthcare as quickly and quietly as they can. Who would want to retain an impossible and unpopular task? The only entities large enough and with some reason to believe that they might find it worthwhile to pick it up will be the pharmaceutical companies. Governments will be pleased to let them have it. But (and there is a big but) they will have to intervene occasionally should the need to maintain profits introduce rules, procedures and limitations that begin to annoy a significant proportion of the population. Votes are precious.

This happens in the USA, where, as we have seen, it is becoming more difficult to remain profitable. Some of the state governments have legislated, for example, that women are entitled to have only one night in hospital after having a baby.

Three years ago, the British Medical Journal pointed out that the medical systems in the USA and UK are mirror images of each other, becoming increasingly alike.8 ‘In the UK medicine is a public endeavour that more and more uses private sector schemes. In the USA it is private endeavour that increasingly is being shaped by public policy.’ My belief is that Australia shall pop up in the middle, more like the USA, with private endeavour increasingly shaped by public policy as the years pass and the conflict between profit and responsibility goes on without end.

If my prediction is correct and the central task has no satisfactory solution, the battle will be endless.

The meaning for us

Where does our profession fit into all this? As a psychiatrist, I will reflect on what this may mean for psychiatry, a significant amount of which (psychotherapy) does not involve the use of medication. A book review in The New England Journal of Medicine mentioned that the value of employer-provided insurance for general medical treatment decreased by 7.2% from 1988 to 1997. In the same period, benefits for the treatment of psychiatric disorders fell by 54%.9

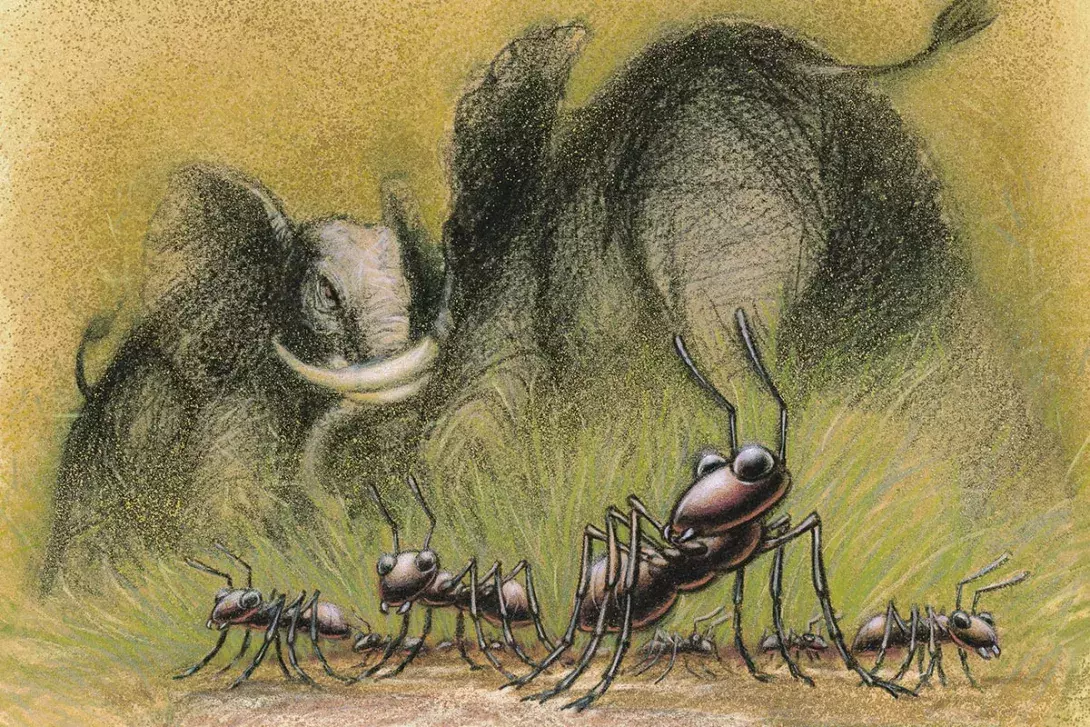

There is no need to say more. We shall be like ants under the feet of fighting elephants. If we can become united, we might muster up a collective bite that will move one or the other of the combatants in a direction that will diminish our chance of being stood on and squashed. If we remain divided, then we shall be squashed one at a time. MT

References

1. The Oregon Plan. Health Outcomes Bulletin 1994; 3: 19-22.

2. Saunders C. AMA backs Medicare reform. Australian Doctor 1999; 12: 13.

3. Health Care Report (video recording) 11 December 1995, ABC Television.

4. The Comparative Performances of US Hospitals: The Source Book. Baltimore: HCIA Inc.; 1999.

5. Ginzberg E. The uncertain future of managed care. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 144-146.

6. Boren SD. The American health care system [letter]. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 918.

7. Manian FA. Where does the buck stop [letter]? N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 240-241.

8. Roberts J. US medicine marches slowly toward UK solution. BMJ 1997; 314: 252.

9. Applebaum PS. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy [book review]. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1088-1089.