Managing dental trauma in general practice

Patients with dental trauma present to general practice clinics or emergency departments for several reasons, including being outside regular dental practice hours and living in communities with poor dental services. Managing acute presentations promptly and facilitating referrals to dental professionals are important to optimise patient outcomes.

- Many patients who sustain dental trauma present to GPs or emergency departments, especially in service-poor communities.

- Dental trauma commonly presents as fractures, luxations or avulsions and may be associated with significant maxillofacial trauma that can be life threatening.

- Bony maxillofacial fractures, large facial lacerations or active uncontrolled bleeding should prompt acute referral to a local emergency department for appropriate surgical opinion and management.

- Panoramic radiographs can help exclude serious pathology and dentoalveolar trauma.

- Local anaesthesia, such as local area infiltration and inferior alveolar nerve blocks, are typically sufficient to manage discomfort in general practice.

- GPs must be equipped to create temporary dental splints to stabilise a patient's dentition until definitive management by a dental practitioner.

The presentation of dental pathology, including dental trauma, to general practice clinics and emergency departments in Australia is not uncommon, with many patients, particularly in service-poor communities, opting to present to medical professionals rather than private dental surgeries for management.1 Reasons for patient presentations to medical professionals, particularly within rural and service-poor communities, include the timing of presentation outside of regular dental practice hours, lack of a regular managing dentist, affordability, lack of private health insurance and location of trauma.1

Presentations to medical professionals for the management of dental pathology make up nearly 1% of all emergency department presentations, with about 66% of these presentations attributed to dental trauma.2 Hence, an understanding of the acute management required for dental trauma is essential for medical professionals. This article provides guidance on the key diagnostic features of dental trauma to allow for appropriate communication and timely management, before referral to dental professionals for definitive management.

Dental anatomy of relevance

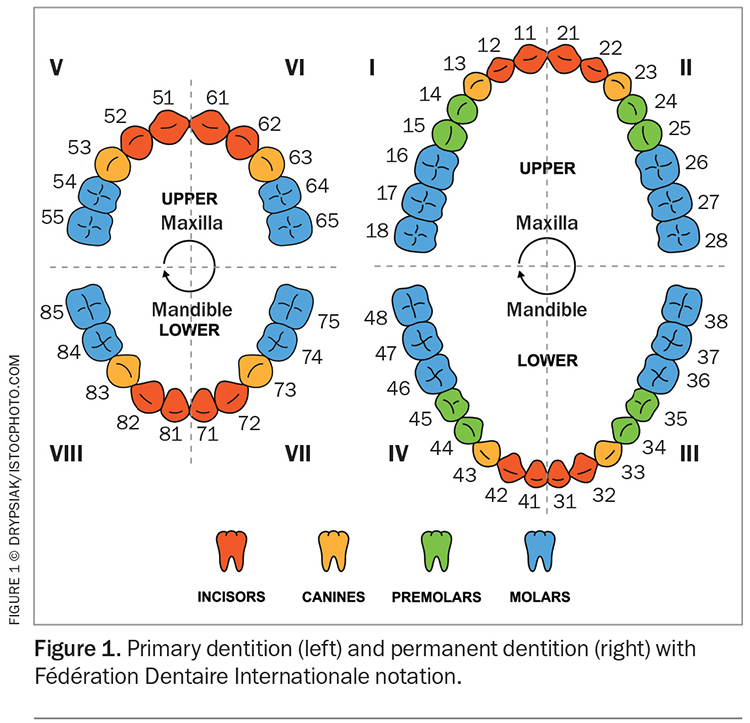

Medical practitioners should have a basic understanding of childhood primary (deciduous) dentition and adult permanent dentition to recognise dental trauma and appropriately communicate to patients. The permanent dentition contains 32 teeth, with the primary dentition limited to 20 teeth; these are each split into four quadrants (Figure 1). A mixed dentition refers to the transition period between complete primary and complete permanent dentition, when a child or adolescent has a combination of both primary and permanent teeth. The naming of the teeth within the respective dentitions follows the Fédération Dentaire Internationale notation in Australia.

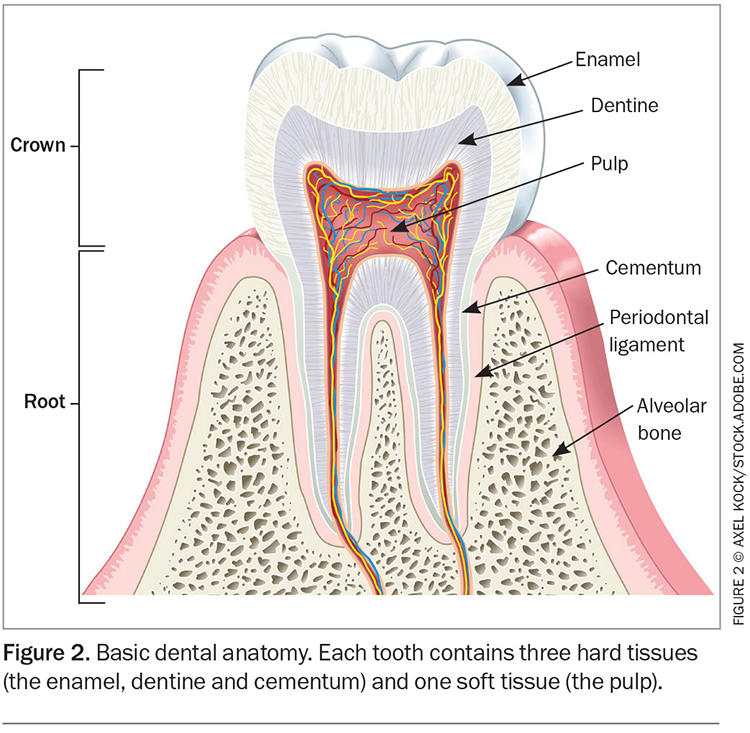

The classification of dental trauma requires an understanding of the anatomical structure of the tooth (Figure 2). The outermost hard layer of the crown of a tooth, the enamel, covers another hard layer, the dentine, which extends to form the root. Within the dentine is the pulp, a neurovascular tissue that is responsible for neural sensation of the tooth. The tooth is retained in its tooth socket within the alveolar bone, a thickened ridge of bone on the jaw, by the periodontal ligament. Knowledge of these structures and of the distinction between the tooth crown and root guides classification and communication surrounding dental trauma, in addition to determining the treatment that may be required.

History taking

Of relevance to patient cosmesis and function, injury of the anterior dentition is the primary site of injury in both the primary and permanent dentition.3 A thorough history should be completed following an initial primary survey of a patient presenting with dental trauma, considering the association of dentoalveolar trauma with other maxillofacial injuries.4 Key types of history relevant to the management of dentoalveolar trauma include, but are not limited to:5

- a basic trauma history, including how the trauma occurred, any associated loss of consciousness and the presence of vomiting, nausea, amnesia or confusion

- a dental trauma history, including time since the trauma occurred, time of any tooth being out of its socket, storage medium for the avulsed tooth, potential for wound contamination, reported occlusal changes and recovery and inhalation or ingestion of tooth fragments

- a basic dental history, including missing teeth prior to the trauma, a history of previous trauma, orthodontic history and previous restorative work

- tetanus vaccination status.6

Of note, dental trauma, particularly with repeated presentation, may be the first sign of interpersonal violence or abuse. As such, it is important to collect appropriate clinical records, including clinical photographs, in the setting of dental trauma.

Clinical examination

Dental trauma may be associated with significant maxillofacial trauma. Thus, a primary survey should be completed early within a clinical examination to identify potentially life-threatening injuries. On examining the oral cavity in the context of dental trauma, a simple yet systematic ‘outside-in’ approach is used.5

- Step 1. Extra-oral assessment: assessments of the mandible and maxilla integrity and associated soft tissue

- Step 2. Intra-oral soft tissue assessment: assessments of lip and buccal mucosal lacerations and associated tooth fragments within lacerations; gingival tears and bleeding; and vestibular, sublingual or palatal bleeding, ecchymosis or oedema

- Step 3. Intra-oral hard tissue assessment: assessments of alveolar bone continuity and fractures, missing or displaced dentition with associated mobility, and changes in occlusion.

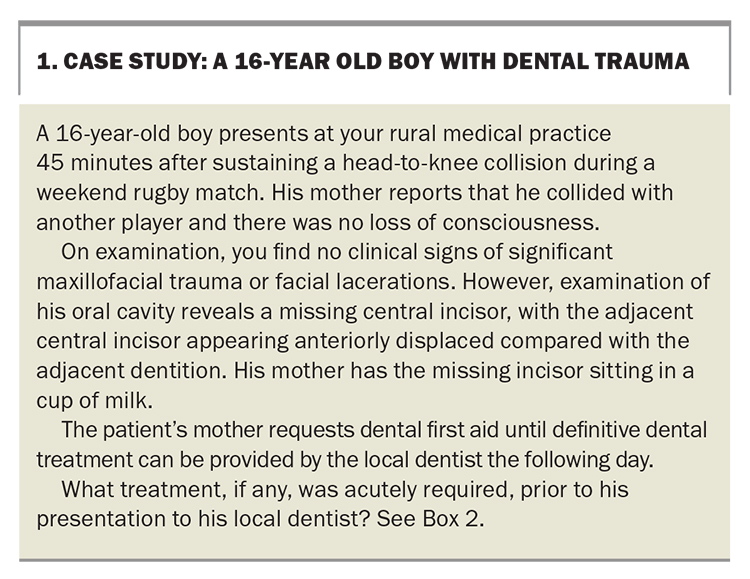

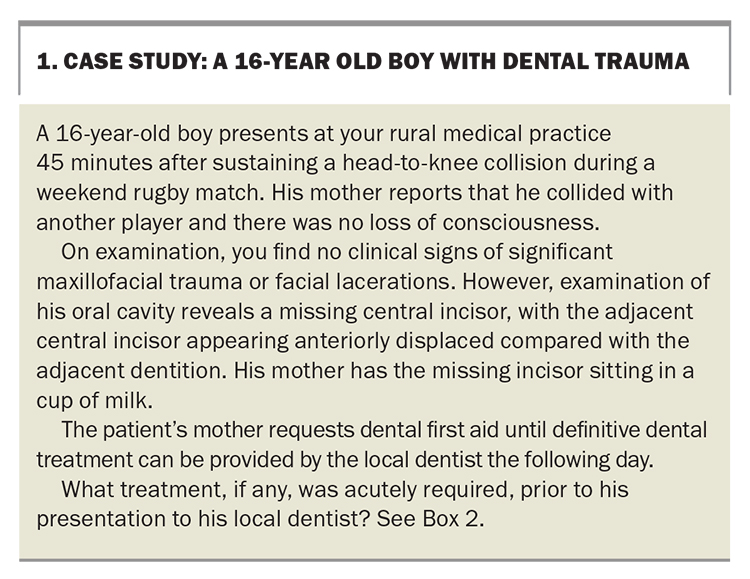

The identification of bony maxillofacial fractures, large facial lacerations or active uncontrolled bleeding should prompt acute referral to a local emergency department for appropriate surgical opinion and management. A case study outlining the examination of a patient with dental trauma is presented in Box 1.

Radiographic assessment

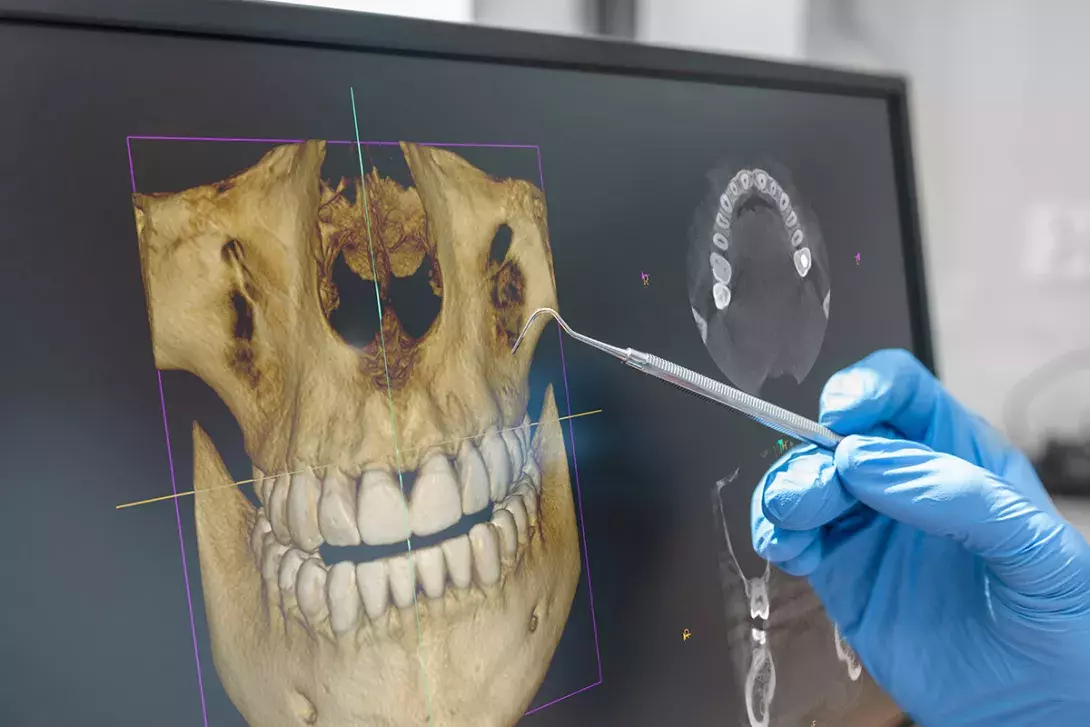

Intra-oral radiographs are the mainstay of assessment for dental trauma; however, because of poor accessibility at general practice clinics and emergency departments, their use is limited. Panoramic radiographs are helpful in the assessment of dentoalveolar trauma and localisation of tooth fragments within surrounding soft tissue. Additionally, the use of chest x-rays in the setting of suspected aspiration should be considered.

Permanent dentition trauma: types and management

The management of dental trauma requires identifying the type of injury.6 The International Association of Dental Traumatology has developed many guidelines to aid diagnosis and management.7 Additional resources, such as those developed by the Australian Dental Association, are also accessible to medical professionals when encountering cases of dental trauma.

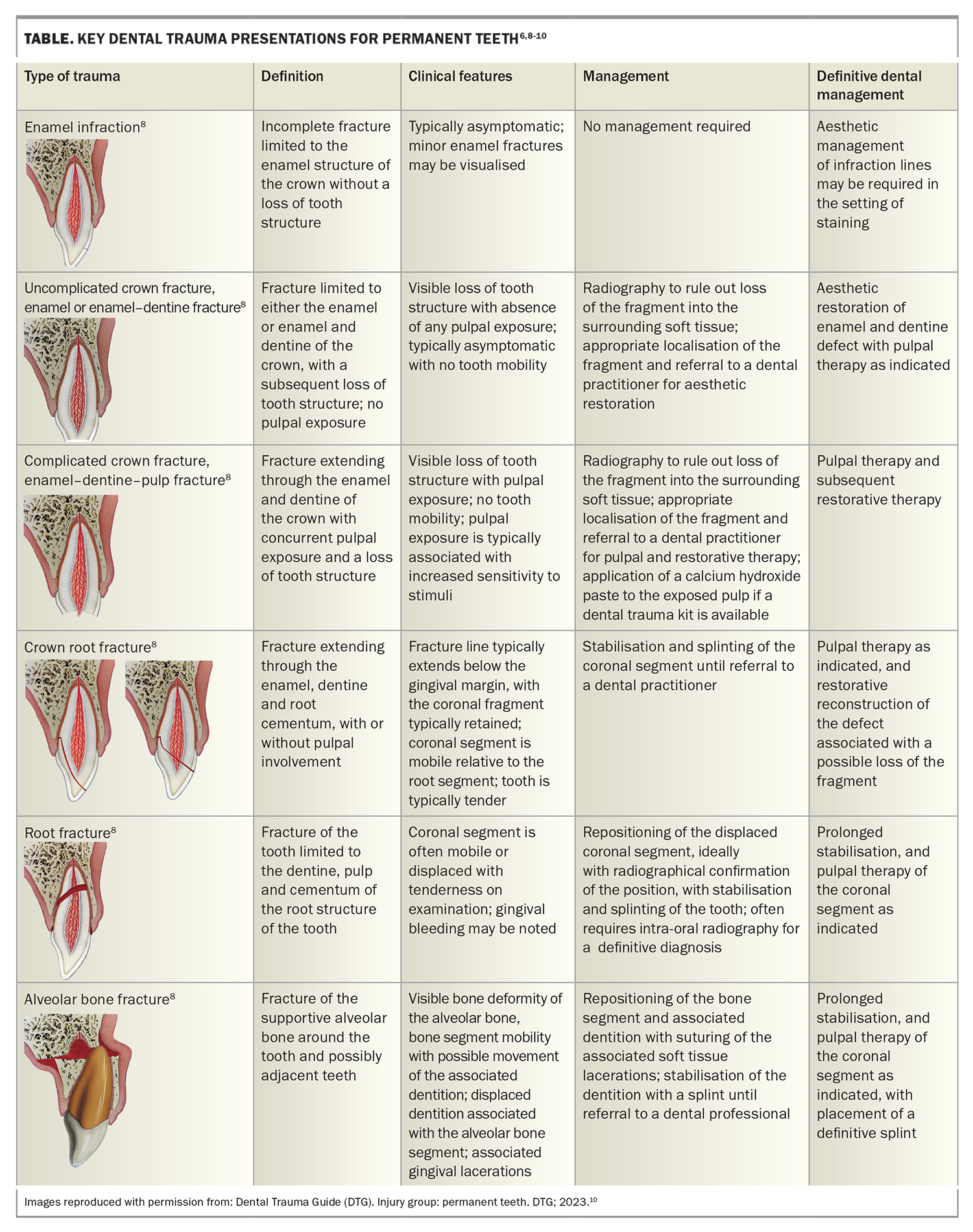

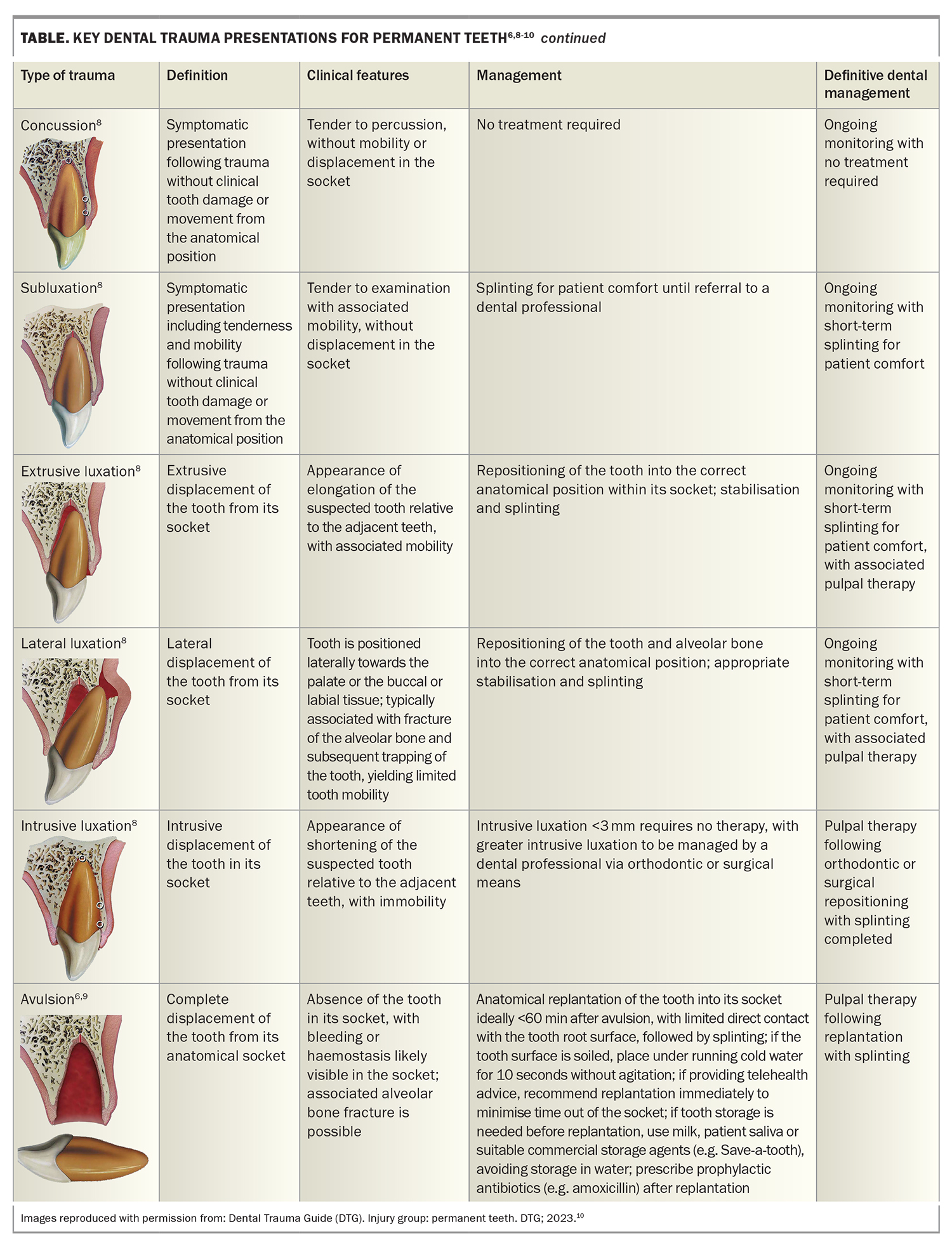

The Table and (Table cont.) outlines key dental trauma presentations, including fractures, luxations and avulsions, and describes management approaches appropriate for medical professionals and definitive dental management approaches.8 These approaches allow appropriate communication to patients regarding the next stage in treatment following acute dental first aid.

General management principles

Dental trauma is typically associated with significant discomfort, with manipulations of tooth position causing further discomfort. As a result, appropriate intra-oral local anaesthesia techniques are required for the management of dental trauma presentations, including soft tissue lacerations. Techniques such as local area infiltration and inferior alveolar nerve blocks are typically sufficient for all management required within general practice. Local anaesthetic agents such as lignocaine, articaine and bupivacaine are suitable for intra-oral use, with lignocaine routinely available within all medical practices.

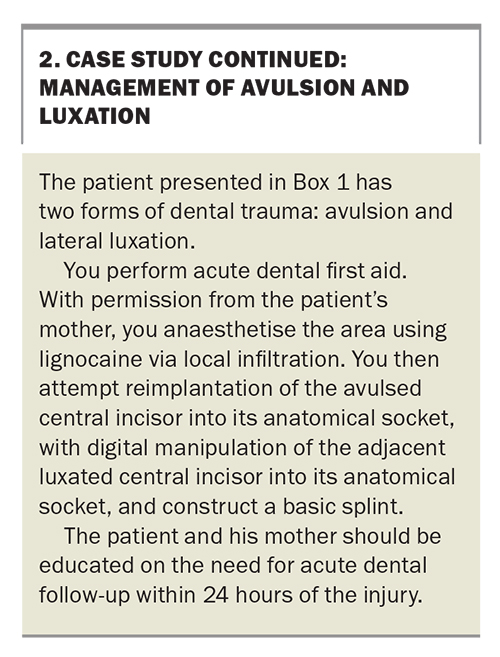

Following the provision of initial treatment, all patients should be counselled about consuming a soft food diet until reviewed by a dental professional. This should be supplemented with further postoperative management, including analgesia and prophylactic antibiotics, and the consideration of adjunctive mouthwashes, such as saline or chlorhexidine, to prevent infection before a dental review. The management approach for the case in Box 1 is presented in Box 2.

Splinting techniques

Splinting serves to stabilise a patient’s dentition after manipulation or replantation following trauma and, as such, should extend to include adjacent teeth with confirmed stability.9,11 Simple splinting techniques include the use of aluminium foil or blue-tac moulded to the affected dentition; however, these techniques should only be used when patients will proceed to acute and definitive management by a dental professional. A more complex alternative is the use of malleable metal from a Hudson mask secured with skin glue.6 Regardless of the technique selected, such splints serve to provide temporary support until a definitive splint can be constructed by the patient’s dental practitioner.

Primary dentition trauma: management

Similar management is required for complicated and uncomplicated crown fractures, alveolar bone fractures and tooth concussions in the primary dentition as in the permanent dentition.11 However, the management of crown root fractures and luxations is different because of the greater depth of permanent dentition compared with the deciduous dentition. This management is often nonemergent, and patients routinely require medical referral to dental professionals for definitive management.11 Regarding avulsions, primary teeth should not be replanted.11

Soft tissue trauma

Common intra-oral soft tissue injuries associated with dentoalveolarw trauma include gingival and mucosal lacerations. In the setting of concurrent loss of the tooth structure, the examination of lacerations should aim to ensure no foreign bodies, such as tooth fragments, are retained within the soft tissue before closure of the injury.

The principles of management of oral soft tissue trauma are similar to those for such injuries in the extra-oral environment, including haemostasis and primary closure of significant lacerations with ongoing bleeding, or that are likely to cause significant cosmetic or functional defects. Dental trauma may be associated with other maxillofacial presentations, including extra-oral lacerations. Referral to appropriate tertiary services, such as oral and maxillofacial or plastic surgery, for the definitive management of facial lacerations of significant functional and cosmetic importance should be considered.

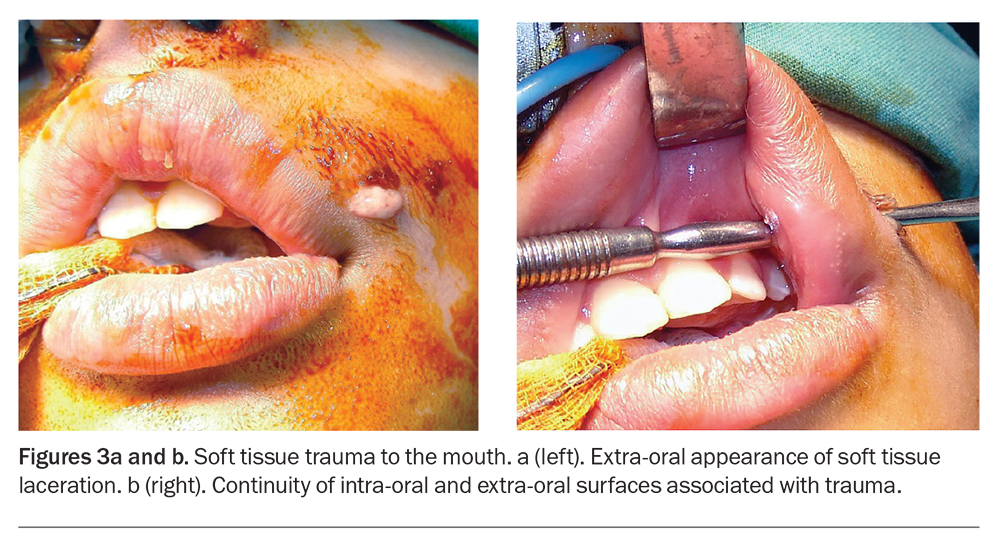

Awareness of contamination with foreign bodies and the oral microbiome should guide antibiotic selection and the consideration of tetanus prophylaxis.6 Figures 3a and 3b show soft tissue trauma extending from the intra-oral to the extra-oral surface, requiring appropriate wound decontamination followed by closure.

Conclusion

The presentation of dental trauma to medical professionals is not uncommon in Australia, particularly within service-poor communities. Dental trauma commonly presents as fractures, luxations or avulsions, which may lead to further maxillofacial trauma. As a result, the timely management of acute presentations with subsequent appropriate referral is important in optimising patient outcomes. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None

References

1. Dorfman DH, Kastner B, Vinci RJ. Dental concerns unrelated to trauma in the pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001; 155: 699-703.

2. Verma S, Chambers I. Dental emergencies presenting to a general hospital emergency department in Hobart, Australia. Aust Dent J 2014; 59: 329-333.

3. Bastone EB, Freer TJ, McNamara JR. Epidemiology of dental trauma: a review of the literature. Aust Dent J 2000; 45: 2-9.

4. Demetriades D, Asensio J. Trauma management (Vademecum). 1st ed. Boca Raron, FL: Landes Bioscience; 2000.

5. Lim L, Sirichai P. Bone fractures: assessment and management. Aust Dent J 2016; 61: 74-81.

6. Beech N, Tan-Gore E, Bohreh K, Nikolarakos D. Management of dental trauma by general practitioners. Aust Fam Physician 2015; 44: 915-918.

7. Levin L, Day PF, Hicks L, et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: general introduction. Dent Traumatol 2020; 36: 309-313.

8. Bourguignon C, Cohenca N, Lauridsen E, et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 1. Fractures and luxations. Dent Traumatol 2020; 36: 314-330.

9. Fouad AF, Abbott PV, Tsilingaridis G, et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 2. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol 2020; 36: 331-342.

10. Dental Trauma Guide (DTG). Injury group: permanent teeth. DTG; 2023. Available online at: https://dentaltraumaguide.org/injury-groups/permanent-teeth/ (accessed March 2023).

11. Day PF, Flores MT, O’Connell AC, et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 3. Injuries in the primary dentition. Dent Traumatol 2020; 36: 343-359.