Diets: evidence-based versus the fads

The average person in Australia is overweight and, consequently, many people choose to follow a diet each year. Practical, evidence-based advice on healthy eating is available from reliable sources, but these sources are not well known or utilised. Thousands of fad diets exist, which promise quick and often miraculous results; however, they mostly offer short-term fixes to long-term health problems.

- Practical, evidence-based healthy eating advice for the general population can be found in the Australian Dietary Guidelines and Australian Guide to Healthy Eating.

- These guidelines are not intended to be used by people with diabetes or other medical conditions: The American Diabetes Association, Diabetes Canada and Diabetes UK regularly publish diabetes-specific guidelines.

- Fad diets are generally not evidence-based and involve altering the consumption of macronutrients to specific proportions or instructing people to consume or avoid specific foods and beverages. They typically promise fast results and mostly produce short-term fixes to long-term health problems.

- Population awareness and adherence to the Australian Dietary Guidelines and Australian Guide to Healthy Eating are poor, with more people following the latest fad diet.

- GPs and other healthcare professionals should recommend the Australian Dietary Guidelines and Australian Guide to Healthy Eating to the general public.

In 2022, nearly two-thirds (65.8%) of adults and more than a quarter (27.7%) of children in Australia were overweight or obese according to their body mass index (BMI), and these rates continue to rise.1 Of greater concern, more than two-thirds (67.9%) of adults had measured waist circumferences that put them at an increased risk of chronic disease (≥94 cm for men; ≥80 cm for women).1

In 2011–12, over 2.3 million people in Australia (13%) aged 15 years and older were ‘on a diet’ to lose weight or for some other health reason, including 15% of females and 11% of males.2 Unsurprisingly, diet books, mostly promoting ‘fad diets’, remain very popular, with more than 1000 new titles published globally each year, and articles published in magazines, in newspapers and online daily.3 Most diets are ineffective in the long term. However, healthy eating remains an important part of weight management and general wellbeing.4,5 The problem is that, perhaps due to all the noise, many people are not aware of what constitutes a healthy diet and therefore follow the latest fad diet.

This article provides a snapshot of dietary habits among people in Australia and draws attention to common fad diets that are unlikely to resolve long-term health problems. In addition, this article describes a healthy diet based on practical, evidence-based advice in the Australian Dietary Guidelines and Australian Guide to Healthy Eating and discusses healthy eating advice for people with diabetes.

Excess adiposity is the primary concern, not weight

Obesity is a chronic, relapsing disease characterised by abnormal or excess adiposity and associated with risks to health, including increased risks of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, dyslipidaemia, metabolic-associated fatty liver disease, reproductive hormonal abnormalities, sleep apnoea, depression, osteoarthritis and certain cancers.4,6 Although the BMI is a useful surrogate at the population level, it is not the best tool for assessing excess adiposity in individuals, unless an individual’s BMI is 35 kg/m2 or greater. The waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio provide better estimates of adiposity.7,8

Successful fat loss

Supervised lifestyle interventions are an essential component of all fat reduction strategies, with behavioural changes, reduction in energy (kilojoule) intake, optimisation of diet quality and increased energy expenditure as integral components for successful treatment and management.4,9 For most people, supervised lifestyle interventions should be first-line therapy and trialled for at least three months before considering pharmacotherapy as an adjunct.4

What is a healthy diet?

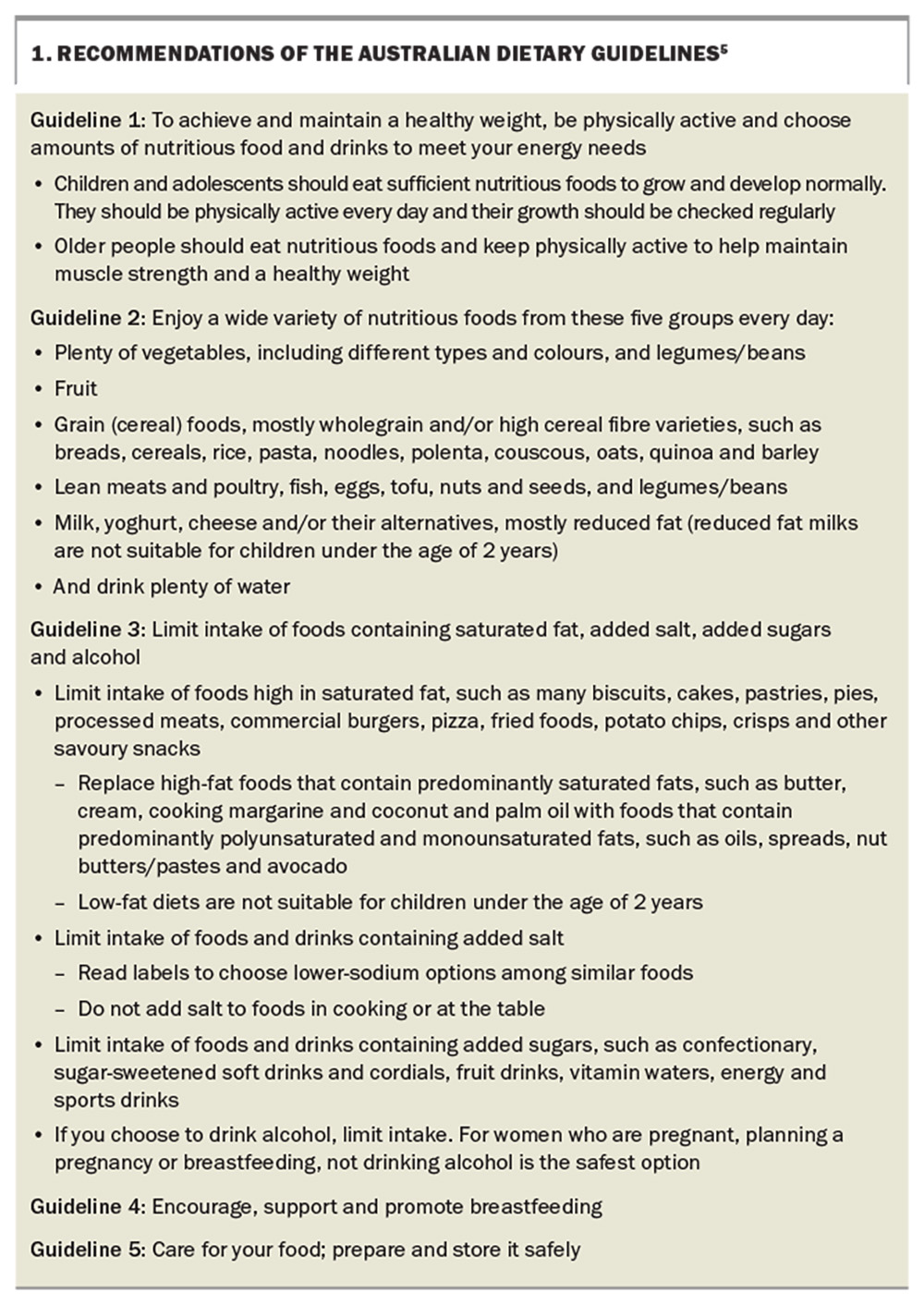

The Australian Dietary Guidelines provide practical guidance for the general population to help people consume a healthy diet.5 Many developed countries worldwide, such as Australia, have been researching and publishing official dietary guidelines for more than 40 years (e.g. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults). Although the specific wording of the guidelines have evolved alongside the underlying science, the general principles have remained broadly consistent with the current iteration. The recommendations of the Australian Dietary Guidelines are listed in Box 1.5

Importantly, these recommendations are for the general population and specifically exclude people with diabetes and other serious medical conditions.5 Therefore, the current Australian Dietary Guidelines are not intended to be used by people with existing diabetes for diabetes management.

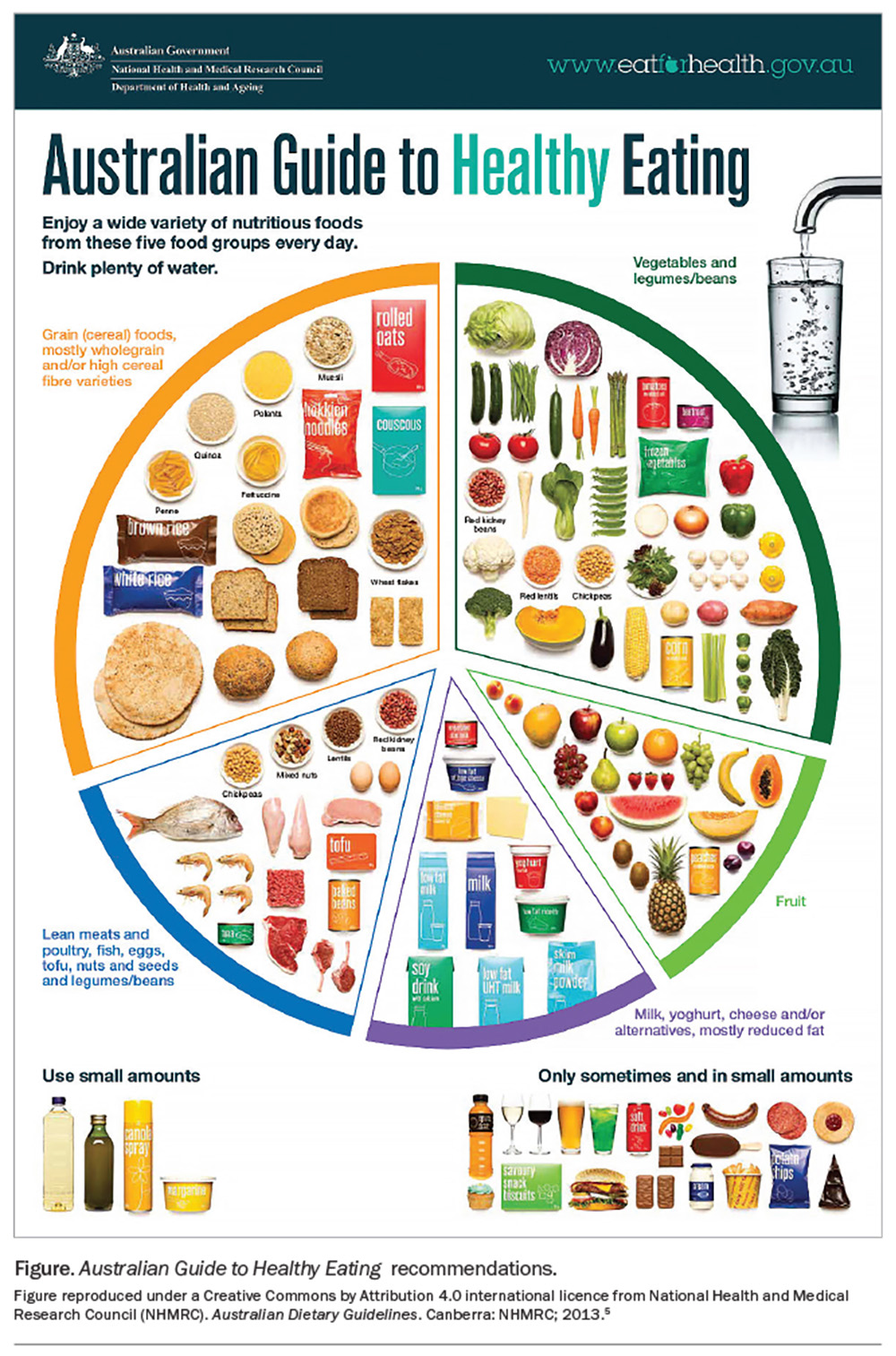

A lesser-known resource that accompanies the Australian Dietary Guidelines is the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating.5,10 This guide uses food modelling to translate the advice from the Australian Dietary Guidelines and develop culturally relevant foundation diets for each age and sex group, meeting nutrient reference values for Australia and New Zealand, and includes a number of different dietary patterns that can be enjoyed by people in Australia.11

Specifically, the dietary modelling addresses four different cuisines:11

- plant-based (lacto-ovo-vegetarian) diets

- diets that include more pasta or rice

- vegetables and legumes as staple items

- omnivore diets.

The pasta- and rice-based diets more closely resemble diets consumed in some Asian or Southern European countries from which many people in Australia have migrated; the dietary culture of these regions has also been incorporated to varying extents into the diets of many other people in Australia.10

The overarching goals of the Australian Dietary Guidelines and Australian Guide to Healthy Eating are to deliver nutrient requirements for people of varying age and sex, activity levels and life stages in a form that is culturally acceptable, that reflects the diets of different socioeconomic groups and that considers the current Australian food supply and food consumption patterns (Figure).5,10

What are Australians actually eating and drinking?

Unfortunately, awareness of the Australian Dietary Guidelines or Australian Guide to Healthy Eating does not appear to be high among the general population and, perhaps consequently, few people are actually following the recommendations.12 An analysis of the most recent National Nutrition Survey found that less than 4% of the population consumed enough vegetables, legumes or beans each day and only 10% met the guidelines for dairy products, whereas one in seven people consumed the minimum number of servings of lean meats and alternatives per day.13

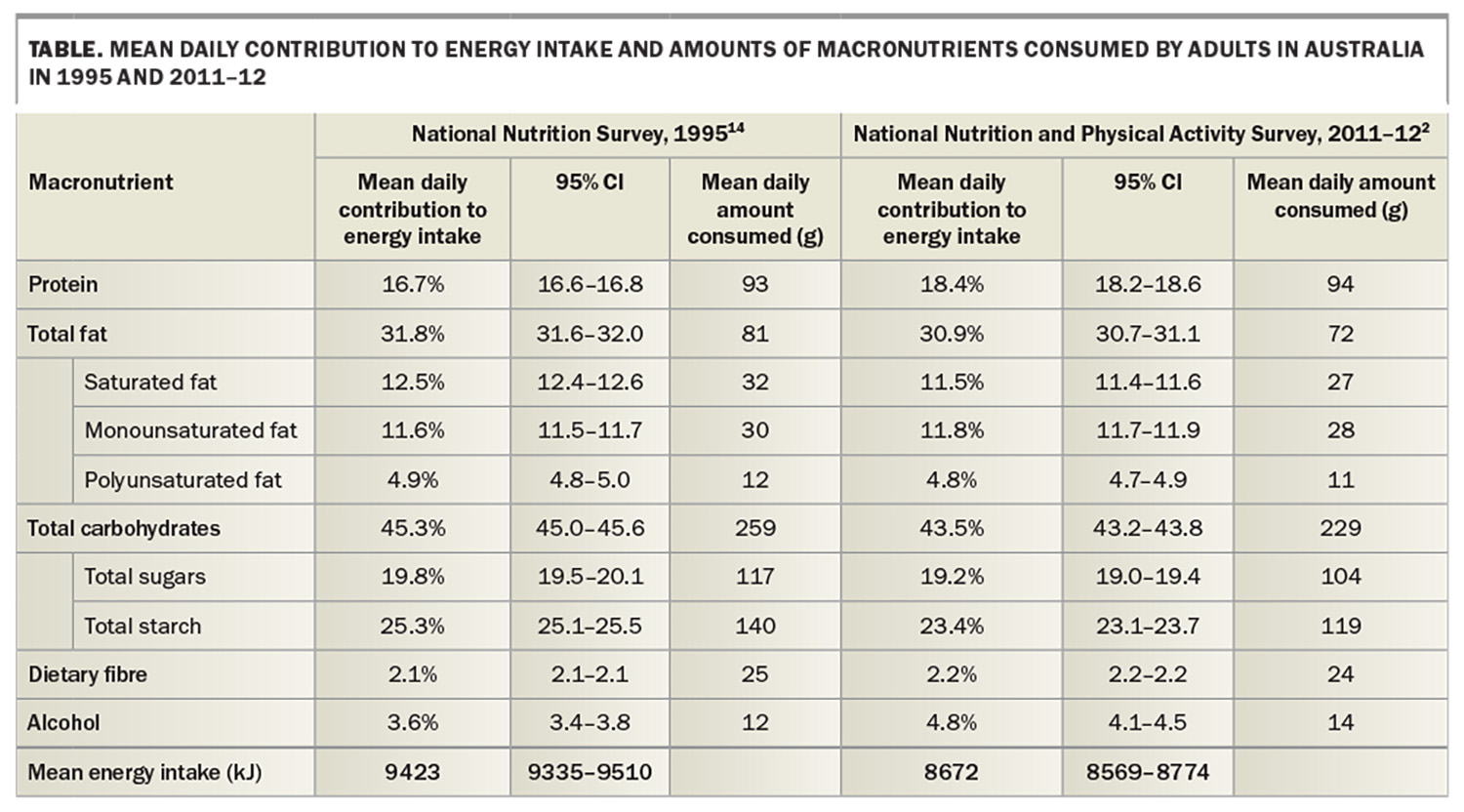

More detailed National Nutrition Survey data are available for the whole Australian population from 1995 and 2011–12, and a summary of the results is presented in the Table.2,14 In 2011–12, people in Australia consumed less energy (in kilojoules) than in 1995, and consumed similar amounts of protein, less fat and carbohydrates (including dietary fibre) and more alcohol.2,14

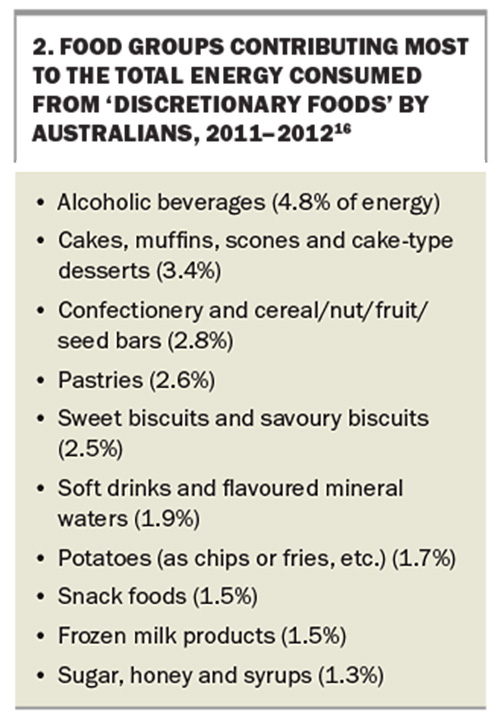

In 2011–12, people in Australia consumed a relatively high-protein diet, moderate in carbohydrates, with more free sugars (10.4% energy) than recommended by the WHO (<10% of energy).15 Of particular concern is the fact that more than one-third (35%) of the total energy consumed was from ‘discretionary foods’: foods and drinks considered to be of little nutritional value that tend to be energy-dense and high in saturated fats, added sugars, salt and/or alcohol.16 The particular food groups contributing the most energy from discretionary foods are listed in Box 2.16 Perhaps surprisingly, alcoholic beverages are the number one source of discretionary energy in the diets of people in Australia. For the 80% of people in Australia who consume alcohol, alcoholic beverages provide about 16% of their energy intake on the days that they are consumed.16

What are fad diets?

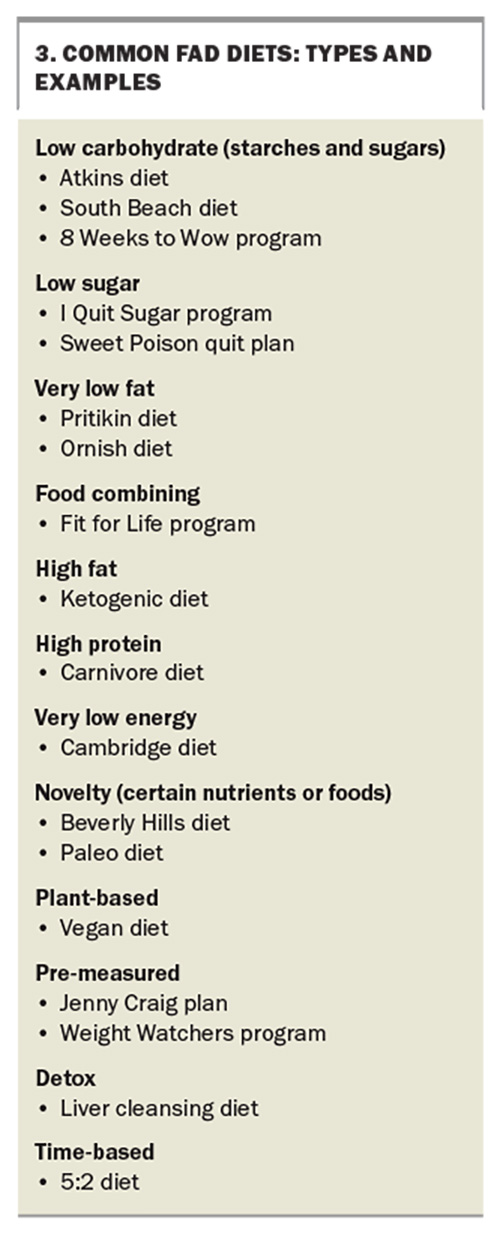

‘Fad diet’ is a broad term that is used to describe dieting methods that alter the consumption of macronutrients (i.e. alcohol, carbohydrates, fat, protein) to specific proportions or that instruct people to consume or avoid specific foods and beverages.17 They typically promise fast results but often limit essential nutrients and, therefore, can be unhealthy, and mostly produce short-term fixes to long-term health problems.17 Short-term consequences, such as dehydration, depression, fatigue, irregular bowel movements and acne, may occur. Long-term consequences include a decreased metabolic rate because of excess lean body tissue loss and the development of disordered eating behaviours (i.e. irregular eating behaviours that may or may not warrant a diagnosis of a specific eating disorder).17,18Box 3 lists some common fad diets that have been popular in Australia and other Western nations over the past 50 years.

A review of the safety and efficacy of all these fad diets is beyond the scope of this article. However, a recent analysis of five fad diets currently popular in Australia (ketogenic diet, paleo diet, intermittent fasting, very low-energy diet and 8 Weeks to Wow program) and two energy-restricted healthy eating principles (Australian Guide to Healthy Eating and the Mediterranean diet) has been published. The diets were compared in terms of nutritional quality, cost, adverse effects and support for behavioural changes using a novel scoring system that incorporated macronutrient distribution, food group intake and micronutrient intake.19 Unsurprisingly, the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating, intermittent fasting and the Mediterranean diet scored the highest. The ketogenic and paleo diets scored the lowest, reflecting their removal of food groups, not meeting certain nutrient reference values and having macronutrient distributions that differed notably from the Australian Dietary Guidelines recommendations.19

Diets for people with serious medical conditions: diabetes

Medical nutrition therapy for people with diabetes is a useful example of evidence-based healthy eating advice for people with a serious medical condition that is not captured by the current Australian Dietary Guidelines or Australian Guide to Healthy Eating.

Diabetes-specific advice is available from a range of diabetes associations. The American Diabetes Association, Diabetes Canada and Diabetes UK regularly conduct systematic literature reviews and publish evidence-based recommendations for the nutritional management of diabetes.20-25 Although the wording varies, all the advice essentially states that there is no single eating pattern recommended for all people with diabetes and that macronutrient distribution can be flexible, should be within recommended ranges and should depend on individual treatment goals and preferences. Examples of healthy eating patterns for diabetes include Mediterranean-style, vegetarian, vegan, low-fat, low-calorie and very low-calorie and low-carbohydrate diets, as well as Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH).25 Furthermore, they recommend food-based dietary patterns that emphasise key nutrition principles, such as the regular consumption of non-starchy vegetables, whole fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts and seeds and lower-fat dairy products and minimal consumption of processed meats, sugar-sweetened beverages and refined grains and starches.20-25 The overarching principles include:

- promoting healthy eating patterns, emphasising a variety of nutrient-dense foods in appropriate portion sizes to improve overall health and to improve glycated haemoglobin levels, blood pressure and cholesterol levels and aid in maintaining body weight

- individualising nutrition needs based on personal and cultural preferences, health literacy and access to healthy food choices

- providing practical tools for day-to-day meal planning

- for those using exogenous insulin, focusing on matching insulin doses with meal composition through carbohydrate counting.

Additionally, the Canadian and UK guidelines recommend replacing high glycaemic index carbohydrates with low glycaemic index carbohydrates in mixed meals, as this approach has been shown to have clinically significant benefits for glycaemic control in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, in addition to that achieved with conventional healthy diets and carbohydrate counting.26,27

Conclusion

Many people in Australia are carrying excess body fat, which contributes to chronic disease risk. Dietary surveys indicate that most people are not following the Australian Dietary Guidelines, and book sales and other popular media consumption indicates that most people are following the latest fad diet instead. Raising awareness of the Australian Dietary Guidelines and Australian Guide to Healthy Eating should therefore be a priority for GPs and other healthcare professionals. MT

Dr Barclay is a consultant to the Glycemic Index Foundation and the National Retail Association, editor of the University of Sydney’s GI Newsletter, and is an author/co-author of several books, including The Good Carbs Cookbook, The Ultimate Guide to Sugars and Sweeteners, Reversing Diabetes and Managing Type 2 Diabetes. He has received an honorarium from Medicine Today.

References

1. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Waist circumference and BMI. Canberra: ABS; 2023. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/waist-circumference-and-bmi/latest-release#key-statistics (accessed July 2024).

2. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Australian Health Survey: Nutrition First Results - Foods and Nutrients. Canberra: ABS; 2014. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/australian-health-survey-nutrition-first-results-foods-and-nutrients/latest-release (accessed July 2024).

3. Hankey C, Whelan K, eds. Advanced Nutrition and Dietetics in Obesity. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2018.

4. Markovic TP, Proietto J, Dixon JB, et al. The Australian Obesity Management Algorithm: a simple tool to guide the management of obesity in primary care. Obes Res Clin Pract 2022; 16: 353-363.

5. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC; 2013. Available online at: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/adg#block-views-block-file-attachments-content-block-1 (accessed July 2024).

6. Hassapidou M, Vlassopoulos A, Kalliostra M, et al. European Association for the Study of Obesity position statement on medical nutrition therapy for the management of overweight and obesity in adults developed in collaboration with the European Federation of the Associations of Dietitians. Obes Facts 2023; 16: 11-28.

7. Sommer I, Teufer B, Szelag M, et al. The performance of anthropometric tools to determine obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 12699.

8. Chan V, Cao L, Wong MMH, Lo K, Tam W. Diagnostic accuracy of waist-to-height ratio, waist circumference, and body mass index in identifying metabolic syndrome and its components in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Dev Nutr 2024; 8: 102061.

9. Adeola OL, Agudosi GM, Akueme NT, et al. The effectiveness of nutritional strategies in the treatment and management of obesity: a systematic review. Cureus 2023; 15: e45518.

10. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). A modelling system to inform the revision of the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating. Canberra: NHMRC; 2011. Available online at: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/the_guidelines/n55c_dietary_guidelines_food_modelling.pdf (accessed July 2024).

11. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Nutrient reference values for Australia and New Zealand including recommended dietary intakes. Canberra: NHMRC; 2006. Available online at: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/nutrient-reference-values-australia-and-new-zealand-including-recommended-dietary-intakes (accessed July 2024).

12. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Poor diet in adults. Canberra: AIHW; 2019. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/food-nutrition/poor-diet/contents/poor-diet-in-adults (accessed July 2024).

13. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 4364.0.55.012 - Australian Health Survey: Consumption of Food Groups from the Australian Dietary Guidelines, 2011-12. Canberra: ABS; 2016. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/4364.0.55.012main+features12011-12 (accessed July 2024).

14. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 4805.0 - National Nutrition Survey: Nutrient Intakes and Physical Measurements, Australia, 1995. Canberra: ABS; 1998. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs%40.nsf/lookup/95e87fe64b144fa3ca2568a9001393c0 (accessed July 2024).

15. World Health Organization (WHO). Guideline: sugars intake for adults and children. Geneva: WHO; 2015. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549028 (accessed July 2024).

16. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Australian Health Survey: Nutrition First Results - Foods and Nutrients, 2011-12 - Australia. Canberra: ABS; 2014. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/australian-health-survey-nutrition-first-results-foods-and-nutrients/latest-release (accessed July 2024).

17. Spadine M, Patterson MS. Social influence on fad diet use: a systematic literature review. Nutr Health 2022; 28: 369-388.

18. Zibellini J, Seimon RV, Lee CM, Gibson AA, Hsu MS, Sainsbury A. Effect of diet-induced weight loss on muscle strength in adults with overweight or obesity - a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Obes Rev 2016; 17: 647-663.

19. Bracci EL, Milte R, Keogh JB, Murphy KJ. Developing and piloting a novel ranking system to assess popular dietary patterns and healthy eating principles. Nutrients 2022; 14: 3414.

20. Sievenpiper JL, Chan CB, Dworatzek PD, Freeze C, Williams SL. Nutrition therapy. Can J Diabetes 2018; 42: S64-S79.

21. Holt RIG, DeVries JH, Hess-Fischl A, et al. The management of type 1 diabetes in adults. a consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2021; 44: 2589-2625.

22. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. Manchester: NICE; 2022. Available online at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28/ (accessed July 2024).

23. Evert AB, Boucher JL, Cypress M, et al. Nutrition therapy recommendations for the management of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014; 37: S120-S143.

24. Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, et al. Nutrition therapy for adults with diabetes or prediabetes: a consensus report. Diabetes Care 2019; 42: 731-754.

25. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 5. Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of care in diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2023; 47: S77-S110.

26. Chiavaroli L, Lee D, Ahmed A, et al. Effect of low glycaemic index or load dietary patterns on glycaemic control and cardiometabolic risk factors in diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2021; 374: n1651.

27. Bell KJ, Barclay AW, Petocz P, Colagiuri S, Brand-Miller JC. Efficacy of carbohydrate counting in type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2: 133-140.