Paediatric vulvar lichen sclerosus – diagnosis and management

Paediatric vulvar lichen sclerosus, a chronic dermatosis that can occur in prepubertal girls, can present with a range of symptoms, including vulvar pruritus, pain, dysuria and constipation. The condition may continue into adulthood and persist lifelong. Early diagnosis and prompt management are essential, with patient adherence to long-term maintenance therapy crucial to maximising control of the disease and minimising its complications.

- Paediatric vulvar lichen sclerosus (VLS) has an average age of onset of 7 years. The condition may continue into adulthood and persist lifelong.

- Common symptoms of VLS include vulvar pruritus, pain, dysuria and constipation.

- The characteristic examination finding of VLS is white atrophic patches or plaques with a figure-of-eight distribution. Ecchymosis, purpura and fissures are also seen. In addition, there may be scarring or distortions in the anatomical structures of the vulva.

- Early diagnosis and prompt management are essential to prevent negative sequelae of untreated disease, such as scarring and reduced quality of life. Patient adherence to long-term therapy is crucial.

- Treatment for VLS involves topical corticosteroid therapy, with choice of potency individualised according to the disease severity and response to treatment.

Vulvar lichen sclerosus (VLS) is a chronic dermatosis affecting the vulva that may extend to the perianal region. The condition has a predilection for prepubertal girls and peri- or postmenopausal women, with the mean age of onset of about 6.5 years in the former group and mid- to late-50s in the latter.1-3 In a Finnish study, the incidence rates were estimated to be 7 per 100,000 in the paediatric population (girls aged 5 to 9 years), and 24 to 53 per 100,000 in postmenopausal women.1

This article discusses paediatric VLS only; a patient case is described in the Box. A review of VLS in adult women was published in Medicine Today in January 2019.4

Clinical presentation

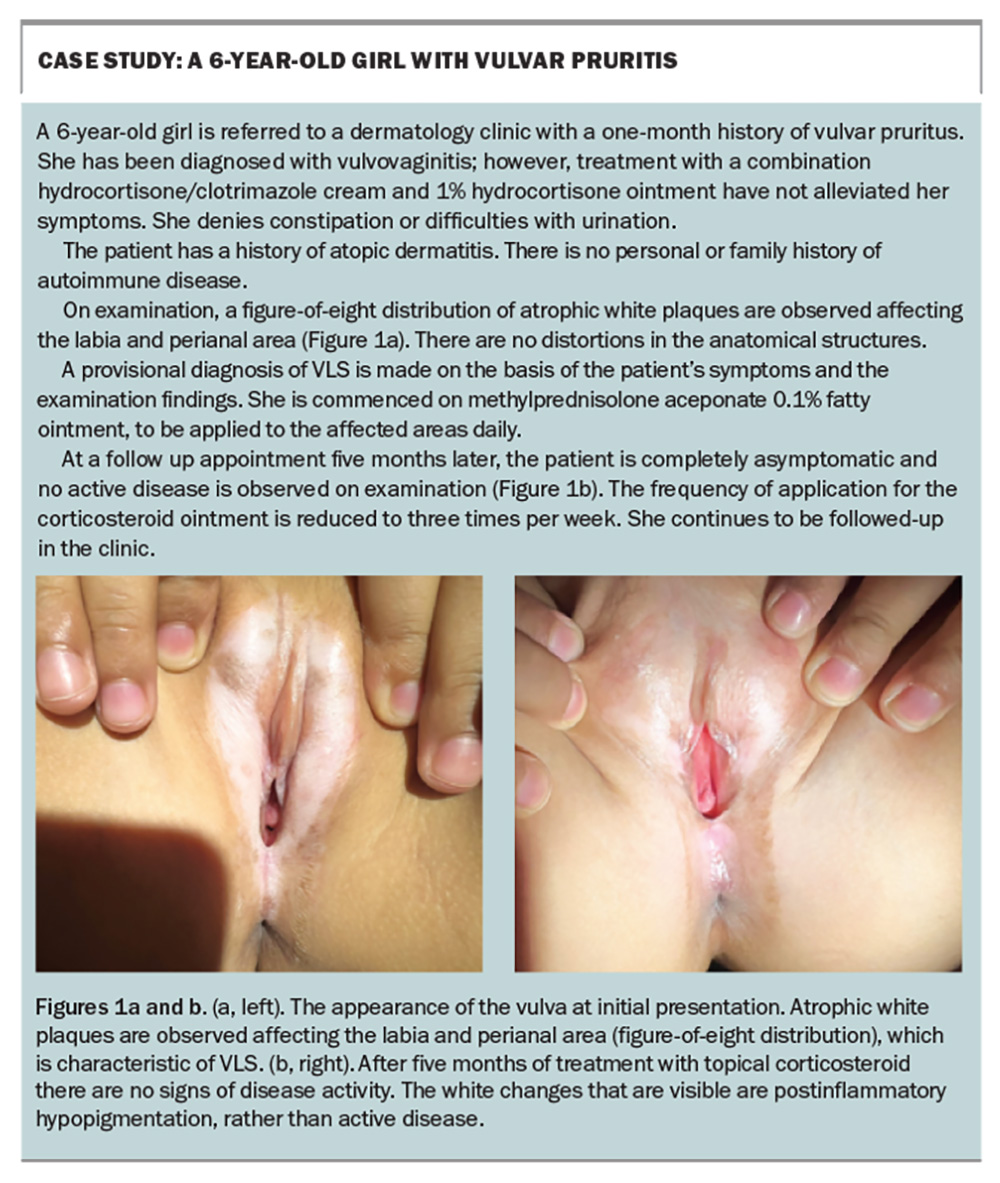

Paediatric VLS usually presents as vulvar itch, pain, dysuria and constipation.2 On examination, observation of white atrophic patches or plaques with a figure-of-eight distribution (involvement of the labia, clitoral hood and perianal area) is characteristic of the condition; other common findings include ecchymosis or purpura, and fissures.2,5 There can be scarring and change in the anatomical structures of the vulva, such as labia minora resorption, labial fusion and burying of the clitoris.2,5

Aetiology and pathogenesis

The exact aetiology and pathogenesis of VLS have not been fully elucidated. However, several theories and potential contributing factors have been proposed, including genetic predisposition and autoimmunity.

Genetic predisposition

A family history of VLS has been observed in several studies.6-8 In a large cohort study conducted in the UK, 12% of 1052 patients with VLS reported a family history of lichen sclerosus, more than half of whom were first-degree relatives.6 Cases of VLS in monozygotic twins have also been documented in the literature. 6,9

In addition, researchers utilising whole-exome sequencing in a genome profiling study have discovered four germline variants shared by seven VLS subjects from two different (unrelated) families but was not found in the control (an unaffected relative from one pedigree).10 The gene variants included ANKRD18A, CD177, CD200 and LATS2, which were proposed to be deleterious to normal protein functioning.

Autoimmunity

Coexisting autoimmune diseases are frequently seen in patients with VLS. Some of the most common include autoimmune thyroid disorders, vitiligo, alopecia areata, pernicious anaemia and morphoea.2,8,11

The findings of cellular and molecular studies support the theory that autoimmunity is a factor in the development of VLS. Histological evidence of immunological changes has been observed in all layers of skin affected by lichen sclerosus compared with normal vulvar skin and other skin (abdomen, breasts, ear) – with increased monoclonal antibody staining for: cytokine interferon (IFN)-γ and IFN-γ receptor; tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α; interleukin (IL)-1α and IL-2 receptor (CD25); and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM)-1 and its ligand CD11a.12,13 In particular, the stronger staining for IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-1α suggests involvement of the Th1 pathway, which is seen in psoriasis and other autoimmune diseases.13

Other factors

The bimodal age distribution of VLS incidence (i.e. peak onset in prepubertal and peri- or postmenopausal) has led to suggestions that hormonal factors, especially pertaining to oestrogen and androgen, play a role in the pathogenesis of VLS.14,15 However, there are limited data to support this theory.

Infections, trauma and chronic irritation have also been proposed as possible triggers for VLS, but the data surrounding these remain inconclusive.7,8,16-20 Further studies will need to be conducted to confirm or refute these associations.

Diagnosis

In the paediatric population, VLS is usually a clinical diagnosis made on the basis of the reported symptoms and examination findings, but it can be confirmed by biopsy. Of note, due to the location and appearance of the disease, which can have ecchymosis or purpura, children with this condition are often inappropriately referred to child protection units.5 This should be avoided, as it may cause profound psychological distress for patients and their families.

Management

Treatment for VLS involves topical corticosteroid therapy. VLS is highly responsive to corticosteroids, and additional treatment is rarely required. At times, an ultrapotent topical corticosteroid may be needed, but the overarching principle is that the potency should be individualised according to the disease severity and the response to treatment.21

It should be explained to patients and their parents that paediatric VLS has the potential to persist lifelong and that long-term (maintenance) topical corticosteroid therapy is crucial to minimise the risk of scarring progression.5,22-24 Once formed, scarring and changes in anatomical structures are irreversible.

It is crucial that clinicians educate patients and their parents early about the safety profile of long-term topical corticosteroids in VLS and address any concerns pertaining to ‘steroid phobia’. Although calcineurin inhibitors are used as adjunctive therapy, they have been shown to be less effective than topical corticosteroids.25 Results of multiple studies have consistently shown that patients who have higher treatment adherence have better disease outcomes and quality of life; they are also much less likely to develop scarring progression and vulvar squamous cell carcinoma.21,23,26,27 ‘Long-term’ therapy stipulates that patients continue applying topical corticosteroid therapy regularly – even when they are asymptomatic and have no signs of disease activity on examination (i.e. during ongoing suppression of the disease). Of note, although VLS is known to increase the risk of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma in adults, the risk in children is less well understood.21 No cases have been reported in children.

As previously mentioned, coexisting autoimmune diseases are frequently seen in patients with VLS for which investigations such as blood tests may be available.2,8,11 However, since testing can be distressing for young children, we do not recommend performing these routinely unless there are clinical indicators to do so. Ultimately, the decision to investigate for autoimmune diseases should involve a shared decision-making process between clinicians, patients and their families, taking into account the patient’s age, medical and family history, and any examination findings suggestive of the presence of an autoimmune disorder.

Long-term outlook

Multiple studies, including a systematic review of 37 publications, have found that most paediatric VLS cases (as high as 75%) do not resolve at puberty.22,24,28 This finding has an important implication in that all paediatric patients with VLS require long-term follow up, just like adult patients. Patients whose disease has gone into remission should be reviewed annually to ensure there is no recurrence.

Conclusion

Paediatric VLS is a chronic dermatosis that may persist lifelong. Early diagnosis and prompt management are crucial to minimise complications, such as scarring and changes in the anatomical structures of the vulva, which are irreversible. Patient adherence to long-term topical corticosteroid therapy is paramount to maximise disease control and quality of life. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Halonen P, Jakobsson M, Heikinheimo O, Gissler M, Pukkala E. Incidence of lichen sclerosus and subsequent causes of death: a nationwide Finnish register study. BJOG 2020; 127: 814-819.

2. Balakirski G, Grothaus J, Altengarten J, Ott H. Paediatric lichen sclerosus: a systematic review of 4516 cases. Br J Dermatol 2020; 182: 231-233.

3. Bleeker MCG, Visser PJ, Overbeek LIH, van Beurden M, Berkhof J. Lichen sclerosus: incidence and risk of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2016; 25: 1224-1230.

4. Fischer G. Vulval lichen sclerosus – diagnosis and treatment. Med Today 2019; 20(1): 21-29.

5. Ellis E, Fischer G. Prepubertal-onset vulvar lichen sclerosus: the importance of maintenance therapy in long-term outcomes. Pediatr Dermatol 2015; 32: 461-467.

6. Sherman V, McPherson T, Baldo M, et al. The high rate of familial lichen sclerosus suggests a genetic contribution: an observational cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24: 1031-1034.

7. Higgins CA, Cruickshank ME. A population-based case-control study of aetiological factors associated with vulval lichen sclerosus. J Obstet Gynaecol 2012; 32: 271-275.

8. Virgili A, Borghi A, Cazzaniga S, et al. New insights into potential risk factors and associations in genital lichen sclerosus: data from a multicentre Italian study on 729 consecutive cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31: 699-704.

9. Doulaveri G, Armira K, Kouris A, Karypidis D, Potouridou I. Genital vulvar lichen sclerosus in monozygotic twin women: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol 2013; 5: 321-325.

10. Haefner HK, Welch KC, Rolston AM, et al. Genomic profiling of vulvar lichen sclerosus patients shows possible pathogenetic disease mechanisms. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2019; 23: 214-219.

11. Cooper SM, Ali I, Baldo M, Wojnarowska F. The association of lichen sclerosus and erosive lichen planus of the vulva with autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol 2008; 144: 1432-1435.

12. Farrell AM, Marren P, Dean D, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus: evidence that immunological changes occur at all levels of the skin. Br J Dermatol 1999; 140: 1087-1092.

13. Farrell AM, Dean D, Millard PR, Charnock FM, Wojnarowska F. Cytokine alterations in lichen sclerosus: an immunohistochemical study. Br J Dermatol 2006; 155: 931-940.

14. Friedrich EG Jr, Kalra PS. Serum levels of sex hormones in vulvar lichen sclerosus, and the effect of topical testosterone. N Engl J Med 1984; 310: 488-491.

15. Taylor AH, Guzail M, Al-Azzawi F. Differential expression of oestrogen receptor isoforms and androgen receptor in the normal vulva and vagina compared with vulval lichen sclerosus and chronic vaginitis. Br J Dermatol 2008; 158: 319-328.

16. Ismail D, Owen CM. Paediatric vulval lichen sclerosus: a retrospective study. Clin Exp Dermatol 2019; 44: 753-758.

17. Edwards LR, Privette ED, Patterson JW, et al. Radiation-induced lichen sclerosus of the vulva: first report in the medical literature. Wien Med Wochenschr 2017; 167: 74-77.

18. Devito JR, Merogi AJ, Vo T, et al. Role of Borrelia burgdorferi in the pathogenesis of morphea/scleroderma and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: a PCR study of thirty-five cases. J Cutan Pathol 1996; 23: 350-358.

19. Powell J, Strauss S, Gray J, Wojnarowska F. Genital carriage of human papilloma virus (HPV) DNA in prepubertal girls with and without vulval disease. Pediatr Dermatol 2003; 20: 191-194.

20. Aidé S, Lattario FR, Almeida G, et al. Epstein-Barr virus and human papillomavirus infection in vulvar lichen sclerosus. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2010; 14: 319-322.

21. Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151: 1061-1067.

22. Smith SD, Fischer G. Childhood onset vulvar lichen sclerosus does not resolve at puberty: a prospective case series. Pediatr Dermatol 2009; 26: 725-729.

23. Kherlopian A, Fischer G. Does compliance to topical corticosteroid therapy reduce the risk of development of permanent vulvar structural abnormalities in pediatric vulvar lichen sclerosus? A retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Dermatol 2022; 39: 22-30.

24. Morrel B, van Eersel R, Burger CW, et al. The long-term clinical consequences of juvenile vulvar lichen sclerosus: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82: 469-477.

25. Goldstein A, Creasey A, Pfau R, Phillips D, Burrows LJ. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial of clobetasol versus pimecrolimus in patients with vulvar lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 64: 99-104.

26. Wijaya M, Lee G, Fischer G, Lee A. Quality of life in vulvar lichen sclerosus patients treated with long-term topical corticosteroids. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2021; 25: 158-165.

27. Wijaya M, Lee G, Fischer G. Why do some patients with vulval lichen sclerosus on long-term topical corticosteroid treatment experience ongoing poor quality of life? Australas J Dermatol 2022; 63: 463-472.

28. Boero V, Cavalli R, Caia C, et al. Pediatric vulvar lichen sclerosus: does it resolve or does it persist after menarche? Pediatr Dermatol 2023; 40: 472-475.