Vulvovaginal symptoms after menopause

Vulvovaginal atrophy causes significant morbidity in women as they age. The primary care physician is in a unique position to use a consultation to discuss a woman’s symptoms with her and to explain the treatment options.

- About 50% of peri- and postmenopausal women report genitourinary symptoms, primarily vaginal dryness and pain with intercourse but, less frequently, vulvovaginal irritation, itching and soreness.

- Appropriately and respectfully initiating questions about these symptoms and signs may allow the woman to discuss her experience and receive the help she needs.

- The vulva and vagina should always be examined when there are symptoms. This will allow exclusion of skin conditions such as lichen sclerosus, which has the long-term risk of vulval cancer.

- Many effective treatments, including lubricants and moisturisers, vaginal oestrogen products and systemic menopausal hormone therapy, are available to treat genitourinary symptoms.

Urogenital health is an essential part of the postmenopausal years in women, from midlife until the end of life. Loss of oestrogen after menopause together with the effects of ageing leads to physical changes and symptoms that may have an impact on a woman’s health, wellbeing, intimacy and quality of life.

Many women who experience symptoms after menopause, such as vaginal dryness, pain with intercourse, incontinence and vulvovaginal irritation, never mention these symptoms when they visit their doctor because they are embarrassed, are shy or feel that is what happens after menopause, so they accept it. The changes may worsen with time, potentially leading to major interference with a woman’s daily life and major psychosocial consequences, including depression and social anxiety.

The GP is the person whom a woman is most likely to trust sufficiently to discuss her genitourinary symptoms with. Appropriately and respectfully initiating questions about these symptoms and signs may allow the woman to discuss her experience and receive the help she needs. The vulva and vagina should always be examined when there are symptoms.

Urogenital changes after menopause

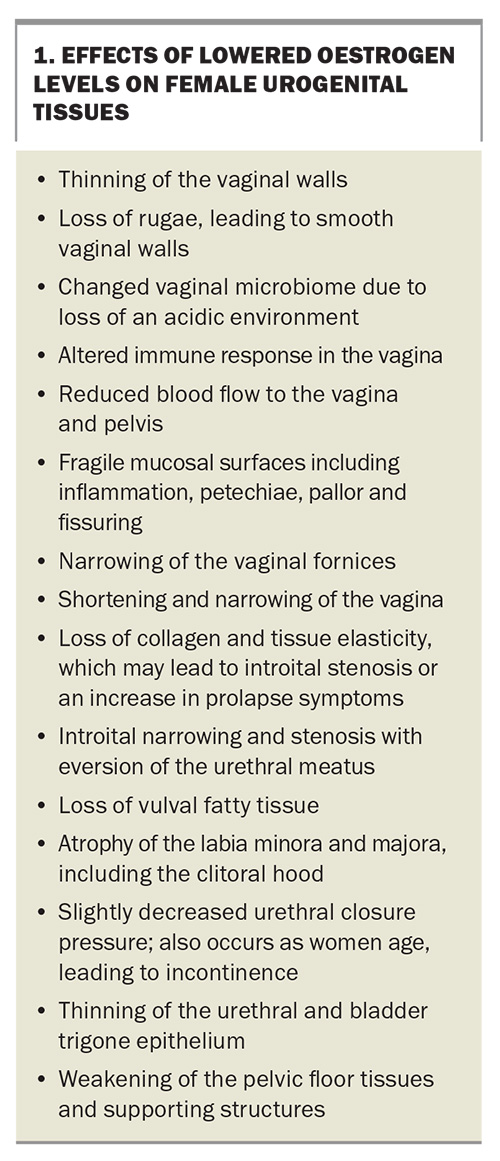

Oestrogen receptors, both alpha and beta, are found in the vagina, urethra, the trigone of the bladder, levator ani muscles, pelvic fascia and supporting ligaments. After menopause, the expression of these receptors diminishes.1 After the cessation of periods, oestrogen levels fall, affecting the urogenital tissues (Box 1). Androgen receptors are also present in the urogenital tract, the vagina, vulva, clitoral, vestibule and labia. Testosterone levels do not decrease at the time of the menopause, whereas dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels decrease significantly during menopause.

The loss of oestrogen leads to changes in function in the vagina, urethra and bladder, and in sexual functioning, resulting in one or many symptoms. These may include:

- vaginal dryness and loss of lubrication with sex

- pain or discomfort with sexual intercourse and bleeding after sexual intercourse

- urinary frequency, urinary urgency or dysuria

- increased urinary tract infections

- dryness, irritation, burning or itching of the vulva

- an increase in genital infections or discharge2

- changes in sexual desire, arousal and orgasm.

- These may also be combined with other menopause symptoms, such as:

- vasomotor symptoms

- aches and pains

- poor sleep

- mood changes.

Quality of life may be impaired as these symptoms can affect body image, relationships, work and social activity.

Risk factors for development of genitourinary symptoms include: menopause, premenopausal bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, premature ovarian failure, other hypoestrogenic states such as hypothalamic amenorrhoea and the postpartum period, cancer treatments including chemotherapy, pelvic irradiation and adjuvant therapies, decreased frequency or absence of sexual activity, lack of vaginal birth and lifestyle factors of smoking and alcohol abuse.

Epidemiology of genitourinary symptoms

About 50% of peri- and postmenopausal women report genitourinary symptoms, primarily vaginal dryness and pain with intercourse but, less frequently, vulvovaginal irritation, itching and soreness. About 25% of women seek help but some report their health professional is dismissive of their complaints as normal ageing.3

In the Vaginal Health: Insights, Views and Attitudes survey, 55% of participants reported symptoms but only 4% attributed them to vaginal atrophy. In the same survey sexual dysfunction symptoms caused the greatest adverse impact on life, because of dryness, pain with intercourse, loss of desire, less intimacy and reduced sexual frequency.4

Women may have signs of atrophy but no symptoms. In the Women’s Health Initiative Hormone Study, about 70% of women at the enrolment examination had clinical evidence of vulvovaginal changes, but only 10% reported moderate to severe genital dryness.5

Among women who have symptoms, some do not realise their cause and that they can seek help; others may be too embarrassed to discuss these symptoms; whereas others do not feel listened to when they seek help. Some women may mention these symptoms because their partner has been complaining and insisting they speak to the doctor about them.

As women age, general health and wellbeing can diminish with illness. This decline can be compounded by bladder, vulval and vaginal symptoms if they are untreated. Menopause symptoms such as vasomotor symptoms mostly improve with time, but the genitourinary symptoms do not. Once a woman has genitourinary symptoms, they tend to worsen with time, so it is important to let the woman know this and offer appropriate treatment.

Some vulval changes occur due to menopause; however, other vulval conditions also increase in prevalence after menopause. These conditions include lichen sclerosus, lichen planus and lichen simplex chronicus, all of which present with similar symptoms and need to be diagnosed and managed long term.

How to improve management and treatment

History and examination

A woman may present for a general check or for a cervical screen. This consultation can be used to ask about genitourinary and bowel symptoms.

When a postmenopausal woman presents with genitourinary symptoms, it is important to make her feel at ease, as she may be very anxious about talking about her symptoms. Ask her to describe her symptoms, how long she has experienced them and how they impact on her life.

You may need to ask further questions. Try not to use technical terms, but rather, language she understands. This will depend on her level of health literacy.

The term ‘vaginal atrophy’ is not liked; preferably use the words ‘vaginal dryness’ or ‘vaginal discomfort’, which help to lead into questions about sex and pain, dryness and lack of libido. Sometimes starting a discussion about urinary symptoms is a way to then ask specific questions about her symptoms relating to dryness and pain.

A health professional should examine their own attitudes in having a consultation about genitourinary symptoms including dyspareunia and other aspects of sexual function. Reasons for difficulty in a consultation may be:

- a lack of time

- a lack of experience and training

- embarrassment for either themselves or the woman

- personal or religious beliefs about sexuality and genitalia.6

The history should also include the woman’s menstrual, gynaecological, obstetric and sexual history as well as any other relevant surgical, medical, psychosocial and family history. If possible, a long appointment should be planned to allow time.

Examination of the vulva and vagina

An examination should always be performed respectfully to make the woman as comfortable as possible. Having a chaperone may be appropriate.

After performing the general examination, first examine the vulva, looking for signs of the atrophic changes of the vulval tissues, the labia, the urethral meatus and the introitus. Look at the colour, signs of pallor or redness, any masses, narrowing or stenosis and thickening of the tissue. Always remember to also look around the anus, as changes may occur there in such conditions as lichen sclerosus. Where there is inflammation or redness, take a swab for microscopy and culture to exclude any bacterial infection.

Perform a vaginal examination, observing the signs outlined above, and exclude any pelvic abnormality. Samples for microscopy and culture should be collected if there is a vaginal discharge (vaginal swab) or any urinary symptoms (mid-stream urine).

Management

Vulval dryness

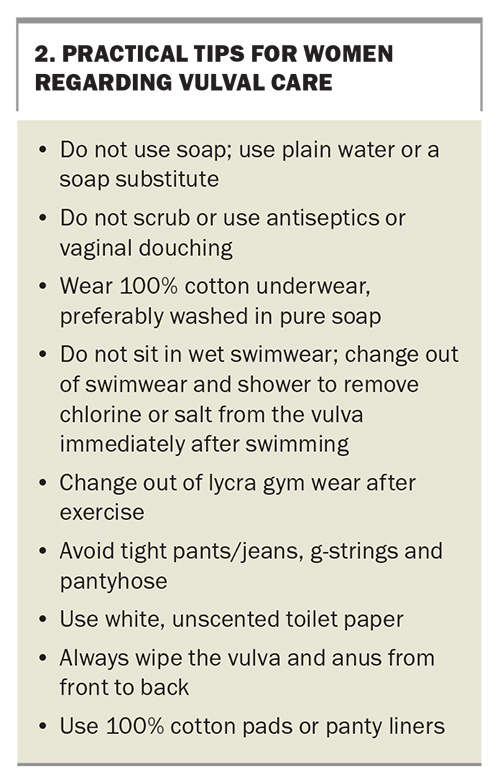

Some women experience vulval dryness and will benefit from using an over-the-counter product for external use, such as petroleum jelly, which forms a barrier, or an intensive treatment ointment that similarly protects and also soothes the skin. The vulval skin requires gentle care, and it is important to instruct the woman in vulval care (Box 2).

Providing written information is helpful. Australasian Menopause Society information leaflets are available online (https://www.menopause.org.au/health-info), and detailed consumer information is also available from Jean Hailes for Women’s Health (https://www.jeanhailes.org.au/health-a-z).

Vaginal dryness and discomfort with intercourse

Initially, simple measures to help vaginal dryness and discomfort may be recommended. Using a vaginal moisturiser reduces dryness by effectively rehydrating the vaginal mucosa. The products available are used about every third day.

Lubricants, used at the time of intercourse, will help to make intercourse more comfortable. Using oils such as olive oil or sweet almond oil can be effective. Commercially available lubricants are not all the same as each other and some may cause side effects; therefore, recommend products that are similar to vaginal secretions in their pH and osmolality.7

Vaginal oestrogens

Vaginal oestrogens have been shown to be very effective in the treatment of vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, urinary urgency and recurrent urinary tract infection.

Products available in Australia are low-dose estradiol vaginal tablets and low-dose estriol vaginal cream or pessaries. Initial treatment is recommended daily for two weeks, then twice per week as a maintenance dose. When the vaginal tissue is atrophic, there is some initial absorption into the systemic circulation, but this diminishes once the vaginal tissues become oestrogenised and are thicker. A progestogen is not needed, even in a woman with a uterus, if only vaginal oestrogen is used.

The blood supply to the vagina is twofold; the upper vaginal venous flow is to the utero-vaginal plexus and the lower vagina, especially the anterior vaginal wall to the haemorrhoidal and pudendal venous plexus. This insight allows us to target vaginal oestrogen to the appropriate areas, with application to the lower vagina when there are introital and lower vaginal atrophy and bladder symptoms.8

Systemic menopausal hormone therapy may treat the vulvovaginal symptoms, but in a small percentage of women who use systemic therapy, atrophic symptoms and signs persist and a local vaginal oestrogen is required in addition.

Vaginal laser therapy has been used in patients in whom oestrogen products were contraindicated, but the potential risks and lack of long-term data on this treatment are concerning. It is not TGA-approved for treating menopausal symptoms.

Intravaginal prasterone is a vaginal pessary of 0.5% DHEA that effectively reduces symptoms of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia. The DHEA is absorbed into the vaginal cell where it is transformed into oestrogens and androgens via a self-limiting process of activators and inhibitors. This process is called intracrinology. It is inserted vaginally each night. The main side effect is vaginal discharge, thought to be due to the one excipient, hard fat. The longest study is 12 months but there are no long-term safety studies in breast cancer or other comorbidities for prasterone.10,11

A product that is not yet available in Australia, and would increase the treatment options, is ospemifene, an oral selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). Ospemifene is oestrogenic on the vagina and has been shown to improve vaginal dryness and dyspareunia. It has a slight oestrogenic effect on the endometrium (endometrial hyperplasia rate, 0.3%) and small potential effect of deep venous thrombosis, similar to other SERMs. Side effects include hot flushes. There are no long-term breast cancer safety studies for ospemifene.

Conclusion

Vulvovaginal atrophy causes significant morbidity in women as they age. Acceptance, embarrassment or lack of knowledge can cause a woman to not seek help for her symptoms. The primary care physician is in a unique position to use a consultation to discuss her symptoms.

History-taking and examination will allow exclusion of skin conditions such as lichen sclerosus, which has the long-term risk of vulval cancer. Appropriate management is dependent on risk factors. There are many treatments available, including lubricants and moisturisers, vaginal oestrogen products and systemic menopausal hormone therapy. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Farrell has received payments as a consultant and speaker from Besins Healthcare, outside the submitted work.

References

1. Gebhardt J, Richard D, Barrett T. Expression of estrogen receptor isoforms alpha and beta in messenger RNA in vaginal tissue of premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001; 185: 1325-1333.

2. Pastore LM, Carter RA, Hulka BS, Wells E. Self-reported urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative. Maturitas 2004; 49: 292-303.

3. Mitchell CM, Waetien E. Genitourinary changes with aging. Gynecol Clin North Am 2018; 45: 737-750.

4. Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Vaginal health: insights, views and attitudes (VIVA) - results from an international survey. Climacteric 2012; 15: 36-44.

5. Gass ML, Cochrane BB, Larson JC, et al. Patterns and predictors of sexual activity among women in the Hormone Therapy trials of the Women’s Health Initiative. Menopause 2011; 18: 1160-1171.

6. Parrish SJ, Nappi RE, Krychman ML, et al. Impact of vulvovaginal health on postmenopausal women: a review of surveys on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. Int J Womens Health 2013; 5: 437-447.

7. Edwards D, Panay N. Treating vulvovaginal atrophy/genitourinary syndrome of menopause: how important is vaginal lubricant and moisturizer composition? Climacteric 2016; 19: 2, 151-161.

8. Eden J. Vaginal atrophy and sexual function. Monograph 15. Available online at: www.healthed.com.au/monographs/vaginal-atrophy-and-sexual-function (accessed September 2024).

9. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA warns against use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal ‘rejuvenation’ or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. 30 July 2018. Available online at: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/ 20201224130103/https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/fda-warns-against-use-energy-based-devices-perform-vaginal-rejuvenation-or-vaginal-cosmetic (accessed September 2024).

10. Wurz G, Kao C-J, DeGregorio MW. Safety and efficacy of ospemifene for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with vulvar and vaginal atrophy due to menopause. Clin Interv Aging 2014; 9: 1939-1950.

11. Labrie F, Archer DF, Koltun W, et al. Efficacy of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on moderate to severe dyspareunia and vaginal dryness, symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy, and of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Menopause 2016; 23: 243-256.