Mild cognitive impairment and dementia: postdiagnostic and ongoing care

A diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or dementia should be followed by establishing a multidisciplinary care plan that is aimed at risk reduction and minimising cognitive decline. This care plan must be reviewed regularly to provide ongoing support to people living with dementia and family carers.

- Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a syndrome defined by cognitive decline without functional decline sufficient to meet a diagnosis of dementia. People with MCI are at a higher risk of developing dementia.

- People given a diagnosis of MCI may not understand the implications of the diagnosis and, therefore, may benefit from education and support to help reduce their risk of progression to dementia.

- Regular reviews for people with MCI should emphasise brain health strategies and monitoring cognition and function.

- Immediately after diagnosis, people with dementia and their families need help to adjust, with the offer of frequent check-ins to plan holistic care and attend to other issues, such as legal matters.

- Dementia has impacts on multiple domains: cognition, function, mental health, behaviour, physical health and family carers. Regular reviews for people with dementia should focus on areas that matter to the patient and their family carers and consider the domains affected by dementia. A multidisciplinary plan should refer to allied health, dementia and aged care services as needed.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a syndrome involving identifiable cognitive decline that does not have an impact on complex activities of daily living. A diagnosis of MCI provides opportunities to minimise factors that might contribute to cognitive impairment, engage in cognitive activities and behaviours that may reduce the risk of dementia, prevent comorbid complications and monitor cognition over time. Dementia describes a syndrome of cognitive decline interfering with daily function. It is usually progressive and affects physical health, psychological health, behaviours and social function.

This article provides an overview of postdiagnostic and ongoing care for people with MCI and dementia, following on from our previous article in the May 2024 issue of Medicine Today discussing the assessment and diagnosis of these conditions.1

Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia

More than 411,100 people in Australia were estimated to be living with dementia in 2023.2 MCI is a relatively new diagnostic entity, first defined in the late 1990s, and officially recognised in the ICD-10 in 2018.3 MCI is a syndrome wherein a person has subjective cognitive complaints and objective impairment without functional impairment or difficulties as a result of cognitive impairment.4 It has a prevalence of 15.56% (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.24–18.03%) in community-dwelling people aged 50 years and older based on a systematic review and meta-analysis.5 People with MCI are 3.3 times more likely to develop dementia than people of the same age with normal cognition. In a study of participants seen in a specialist clinic, 14.9% of people diagnosed with MCI developed dementia within two years.4 Similar to dementia, MCI has many causes. It is important to understand that in 60% of people with MCI, the condition will remain the same or improve.

Postdiagnostic care for people with mild cognitive impairment

Postdiagnostic care for people with MCI is aimed at reducing cognitive impairment and minimising the risk of progression to dementia. Much of the potential to improve cognition in people with MCI arises from management of known contributing factors of cognitive impairment. These include polypharmacy (e.g. high anticholinergic load), mood disorder (e.g. depression and anxiety), obesity and its complications (e.g. poorly controlled diabetes), poor sleep (e.g. obstructive sleep apnoea), cerebrovascular risk factors and hearing loss. Patients with multiple contributing factors have a clear potential to improve cognition. The CogDrisk (https://cogdrisk.neura.edu.au/) is a validated Australian tool that can be used to tailor risk reduction advice for people with MCI.6 The patient completes a detailed online risk questionnaire, and the tool produces a personalised report identifying modifiable risk factors.

There are many studies of people with MCI showing that individual interventions can improve cognition. For instance, multicomponent exercise (combined aerobic, endurance, balance and flexibility) improves global cognition and executive function in people with MCI.7 Computerised cognitive training improves specific cognitive domains (e.g. memory, executive function).8 Multidomain interventions (e.g. combination of physical activity, socialisation, cognitive training and nutritional advice) are better than individual interventions in improving cognition.9 Studies evaluating whether multidomain interventions in people with MCI reduce the risk of progression to dementia are ongoing.

Receiving a diagnosis of MCI may be beneficial for some people, but not for others. Research suggests that people with MCI often find the diagnosis confusing or hard to understand.10 They may have a range of reactions. Some people will feel relief that they do not have dementia, whereas others will experience fear of developing dementia in the future. Many people with MCI do not know what to do after the diagnosis.11 When discussing MCI, it is important to differentiate it from dementia and highlight the opportunities for dementia risk reduction.12

Dementia Australia offers the ‘Thinking Ahead’ program (https://www.dementia.org.au/get-support/mild-cognitive-impairment-thinking-ahead) for people with MCI, which is based on the Healthy Brain Ageing Cognitive Training Program.13 This involves online group psychoeducation on cognitive strategies and modifiable risk factors, as well as computer-based cognitive training. A nutritional supplement containing ingredients (e.g. uridine monophosphate, choline, omega 3 fatty acids) intended to support memory and cognitive function in people with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has shown small but inconsistent benefits in terms of specific cognitive outcomes without slowing disease progression.14 The supplement costs about $150 per month.

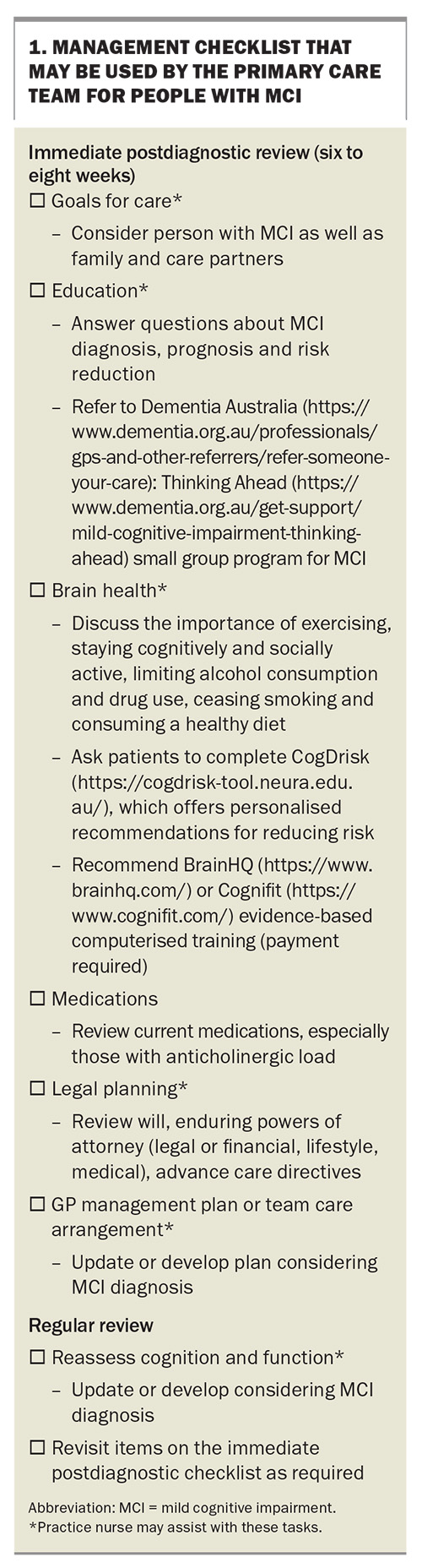

A management checklist for immediate postdiagnostic and regular review of MCI is presented in Box 1.

Postdiagnostic care for dementia

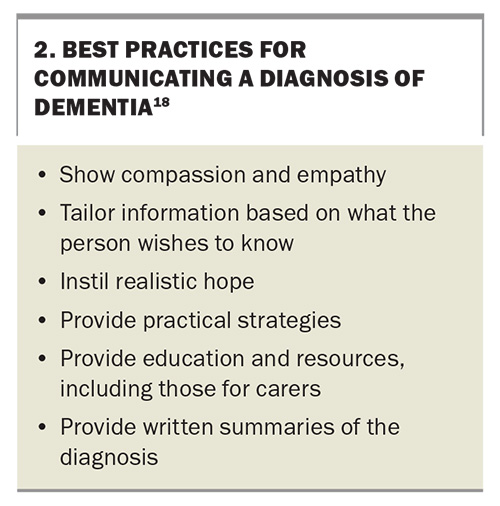

Postdiagnostic care for people with dementia is aimed at effective communication and enablement. Some people may say that the diagnosis is a relief, whereas many people with dementia and their carers find that being given the dementia diagnosis is a negative experience and report being unable to process any additional information after being told it is dementia.15 Kate Swaffer, a prominent dementia advocate, described her experience as ‘prescribed disengagement’, saying that the way her diagnosis was communicated led to her withdrawing from work and society, and developing increased feelings of fear, defeat and depression.16 Self-stigma around dementia means that people with dementia may be at a small but higher risk of suicide, particularly immediately after diagnosis; therefore, offering hope is an important part of the process of delivering a diagnosis.17 GPs giving the diagnosis can communicate this over several appointments using graduated language. Some strategies that can be used when communicating a diagnosis of dementia are listed in Box 2.18

Timely and appropriately targeted postdiagnostic support can help patients and family members adjust to the dementia diagnosis and support access to additional services. In Australia, postdiagnostic care services can be difficult to navigate as there are many different stakeholders and service providers that vary enormously across the country. Some memory clinics have limited capacity to provide postdiagnostic support, often leaving this to the person’s GP.19-21 Community services through My Aged Care have their own challenges, with long waiting lists and limited services to support the needs of people with dementia and their care partners.

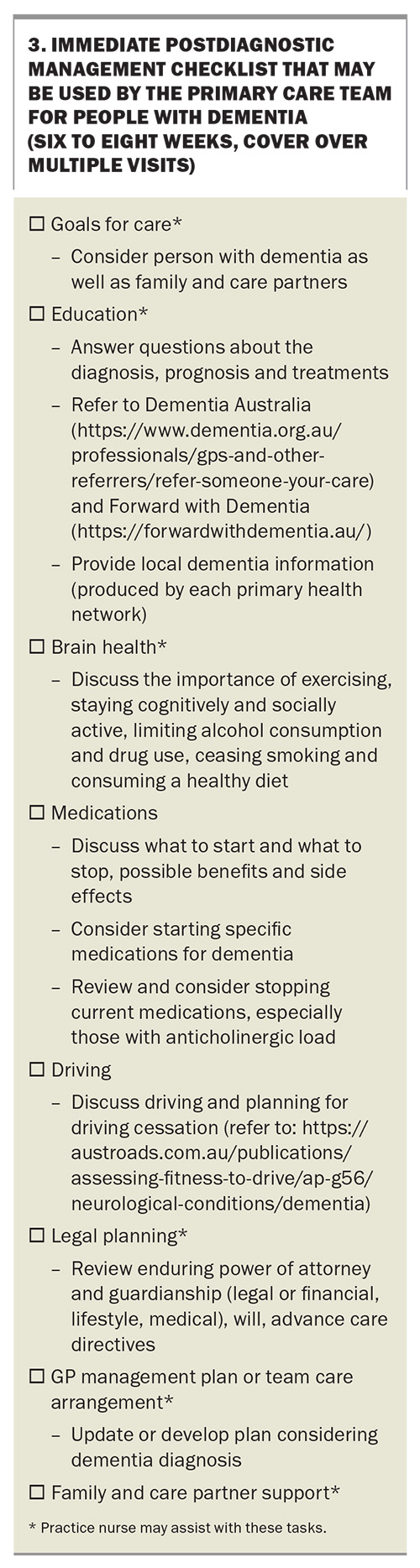

Some people and family carers will value frequent follow-up appointments to provide advice and information about dementia. These visits are an opportunity to discuss and address concerns that may be affecting the patient’s and their carers’ quality of life adversely. People often look to their doctors for this advice. Timely and ongoing treatment and support in primary care may improve care and mitigate some of the negative impacts of a dementia diagnosis. A management checklist for people recently diagnosed with dementia is presented in Box 3.

Ongoing dementia management

Ongoing dementia management involves addressing multiple domains to maximise the person’s quality of life. Clinicians must take a proactive, patient-centred, evidence-based approach to ongoing dementia support. Goals of care should maximise quality of life through maintaining the person’s independence while ensuring their safety and comfort as the condition progresses. Although each person with dementia and their family carer is different, this typically involves the following:

- optimising the management of comorbidities

- managing risk factors to slow progression

- supporting function and social participation in early-stage dementia

- attending to behavioural expressions of unmet needs and safety in mid-stage dementia

- ensuring comfort in late-stage dementia.22

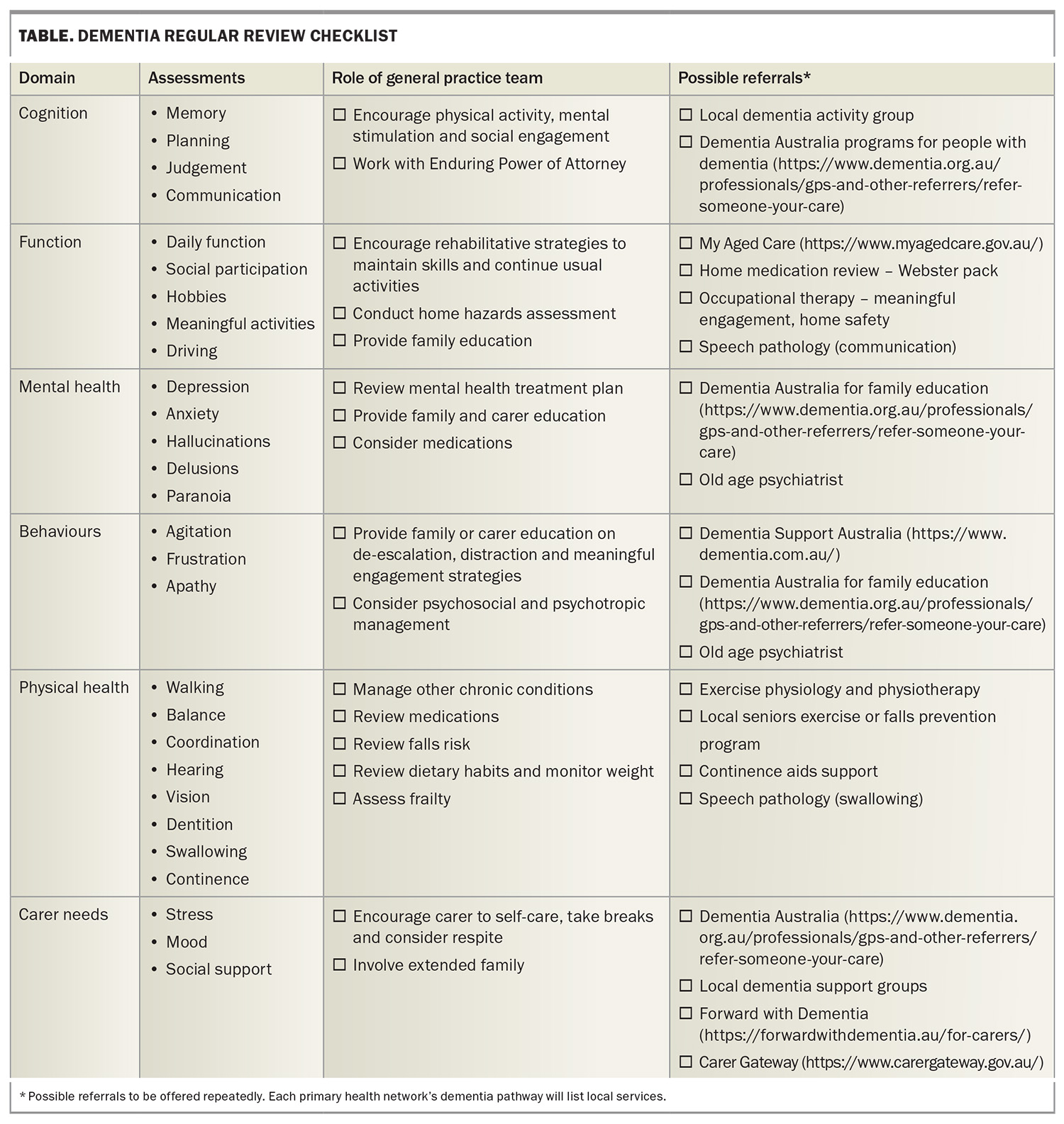

A checklist of assessments and actions grouped by the domains impacted in dementia is presented in the Table.

Cognition

Decline in cognition is one of the defining features of dementia. Cognitive decline precedes functional decline and affects memory, language, attention, executive functioning and visuospatial functioning, with different patterns of deficits seen in different types of dementias.23

Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine result in modest reductions in cognitive decline in people with AD, mixed AD and other dementias, although they are not currently indicated for MCI.24,25 They should be considered symptomatic treatments as opposed to disease-modifying agents. These agents are listed on the PBS for specialist-confirmed AD as single agents on authority script, and both drug types cannot be concurrently claimed through the PBS. To qualify, patients must have a baseline Mini-Mental State Examination score of 10 or higher for cholinesterase inhibitors and 10 to 14 for memantine.

Cognitive training involves practising structured cognitive tasks (e.g. a memory or attention game) usually administered via a computer or handheld device to improve or maintain cognition. A Cochrane review found that, compared with nonspecific activities, cognitive training has benefits in terms of overall cognition and some specific cognitive abilities, which last for at least a few months in people with early- to mid-stage dementia.26

Cognitive stimulation therapy involves engagement in a range of activities (e.g. bowling, memory games) and discussions (e.g. articles in today’s newspaper, reminiscence), usually in a group setting aimed at general enhancement of cognitive and social functioning. In people with mild to moderate dementia, it has small benefits in terms of cognition, communication, interaction, daily function and mood, compared with usual care or structured activities.27 There remains an evidence gap in relation to the clinical significance of the benefits of longer-term cognitive stimulation therapy. Cognitive stimulation groups are offered by aged care providers, often as part of day respite.

Physical activity slows the decline in global cognition and executive function in people with dementia; however, there are differences between the findings of systematic reviews on whether aerobic exercise, resistance exercise or multicomponent exercise (e.g. combined aerobic, balance flexibility) may be more beneficial.7,29-30 There are few exercise groups specifically for people with dementia. Exercise physiologists and seniors’ gyms can help people with dementia exercise safely.

Function

Decline in function is a core feature of dementia. Occupational therapy and reablement approaches can maintain or improve function.7,31-33 Physical activity can also help maintain activities of daily living in people with dementia living in the community and in residential aged care.7,34

Occupational therapy interventions typically involve working with the person with dementia and carer in their own home over multiple sessions and may involve environmental modifications, development of tailored activities and education enabling better function.31 For example, the Care of the Older Person in their Environment (COPE) program (https://copeprogram.com.au/therapists/) is a home-based, structured occupational therapy program involving the person with dementia and their carer. The program has been shown to improve function and engagement in people with dementia, as well as carer wellbeing and confidence in providing meaningful activities.35 The COPE program has been adapted and implemented in Australia and is available through some health services and home care package providers.36

Mental health

People with dementia have poorer mental health than those of the same age without dementia. A meta-analysis of 20 studies found pooled prevalence rates of 39% for depression (95% CI, 34–44%), 39% for anxiety (95% CI, 33–45%) and 54% for apathy (95% CI, 47–61%), with no differences by stage or type of dementia.37 A Swedish registry study found that people with dementia are much more likely to be given a new diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder (e.g. depression, anxiety, stress-related disorders, substance use, psychotic disorders) in the three years before dementia diagnosis and immediately after the diagnosis.38

It is important to differentiate depression symptoms that are predominantly caused by dementia from symptoms that are caused by a major depressive disorder. Cognitive behavioural therapy reduces depression symptoms in people with MCI and AD who were able to participate in the trials.39 Clinical trials suggest that antidepressants are less effective in treating depression in dementia.40 Clinicians should ‘start low and go slow’, monitor closely for adverse effects and deprescribe if the treatment is not helpful.

Behaviour

People with dementia can exhibit behavioural changes. These are often referred to as behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), but the preference of people with dementia and family carers is to call them ‘behaviour changes’ to emphasise that changes can arise because of unmet needs.41

Nonpharmacological measures should be first-line management, and antipsychotics should only be prescribed to manage behaviour changes in people with dementia as a last resort for symptoms such as distressing psychotic symptoms, agitation or aggression that is a direct threat to themselves or others.22,42,43 Nonpharmacological strategies should be tailored to meet any unmet needs and may include environmental changes, engaging activities, carer education and assessment. Dementia Support Australia is a national service offering a GP advice line, 24/7 advice and support for family carers and aged care staff, and home and facility visits (see Box 4). A barrier to the use of nonpharmacological strategies in some residential aged care facilities is a lack of staff, high staff turnover and inconsistent training. GPs might be pressured to prescribe psychotropics before an adequate trial of nonpharmacological strategies.44

If antipsychotics are prescribed, then it should only be for a trial for the short-term management of behaviour changes in people with dementia (12 weeks). Informed consent must be obtained and documented. The literature suggests benefits in 20 to 30% of patients in terms of symptoms of aggression and psychosis. Antipsychotics are associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular events, falls and mortality. Patients should be reviewed regularly for efficacy and adverse events, and treatment should be ceased if they do not respond.43 Antipsychotics should not be used for symptoms such as wandering or calling out. Clinicians are advised to ‘start low and go slow’. There are specific guidelines for the use of antipsychotics in residential care.42

Physical health and comorbidities

People with dementia have an average of 4.6 other chronic illnesses.45 Dementia is associated with an increased risk of many conditions including delirium, weight loss and malnutrition, epilepsy, frailty, sleep disorders, oral disease and visual problems.46 Furthermore, dementia has impacts on gait and balance, increasing a person’s risk of falls.47 Acute exacerbations of comorbidities, such as cardiac and respiratory diseases and recurrent urinary infections, can precipitate delirium, especially if the condition is sufficiently severe to require hospital admission; this can result in an irreversible decline in cognitive performance even after the delirium has resolved.

Although people with dementia often have additional chronic diseases (e.g. cardiovascular diseases, diabetes), there is relatively little research or guidance on managing these intercurrent illnesses.48 People with dementia should have equivalent access to diagnosis, treatment and care services for comorbidities to those for people without dementia.49 It is the functional impact of dementia and patient wishes that should inform the intensity of the management of comorbidities. For example, in late-stage dementia when the monitoring of treatment or control of diet is more difficult, simplifying diabetes medication regimes might be appropriate to avoid hypoglycaemia and associated complications in diabetes.50 Management strategies need to consider the person’s cognitive abilities and involve family and professional carers. In addition, with the permission of the patient, all healthcare professionals involved in care should be made aware of the dementia diagnosis so that care provided can be modified appropriately. This includes non-GP specialists, practice nurses, the pharmacist, the podiatrist, the optometrist, the audiologist and other allied healthcare providers.

Family carers

The most commonly reported needs of carers of people with dementia are knowledge and information about the disease and care options, support from others (e.g. professionals, friends and family), formal care, care co-ordination and continuity, financial support, inclusion in care planning and training in communication skills.51 Psychosocial interventions, particularly those with both educational and therapeutic components that are delivered in groups, have positive impacts on depression and burden, and delay institutionalisation of the person with dementia.52 Family carers tend to need more support as dementia progresses and should be monitored for depression and burnout. Dementia Australia (https://www.dementia.org.au/get-support) offers carer programs, and other supports can be accessed through the carer gateway (https://www.carergateway.gov.au/).

Australian system constraints on supporting people with dementia

Unfortunately, dementia services in Australia are fragmented, difficult to navigate and differ by region. For this reason, primary care plays a crucial role in dementia support providing ongoing education, care co-ordination and navigation, and support.53 Resources to help older people obtain dementia services are listed in Box 4.

Conclusion

People with dementia and family carers require ongoing review and support given the many domains affected by dementia. Their primary care team can provide continuity of care, ongoing information and advice and referrals to services when required are listed in Box 4. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: A list of competing interests is included in the online version of this article (www.medicinetoday.com.au).

References

1. Yates M, Daly S, Long M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and dementia: detection and diagnosis. Medicine Today 2024; 25(5): 20-24.

2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Dementia in Australia. Canberra: AIHW; 2024. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/dementia/dementia-in-aus/contents/population-health-impacts-of-dementia/prevalence-of-dementia (accessed October 2024).

3. Kasper S, Bancher C, Eckert A, et al. Management of mild cognitive impairment (MCI): the need for national and international guidelines. World J Bio Psychiatr 2020; 21: 579-594.

4. Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, et al. Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 2018; 90: 126-135.

5. Bai W, Chen P, Cai H, et al. Worldwide prevalence of mild cognitive impairment among community dwellers aged 50 years and older: a meta-analysis and systematic review of epidemiology studies. Age Ageing 2022; 51: 8.

6. Kootar S, Huque MH, Eramudugolla R, et al. Validation of the CogDrisk instrument as predictive of dementia in four general community-dwelling populations. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2023; 10: 478-487.

7. Yan J, Li X, Guo X, et al. Effect of multicomponent exercise on cognition, physical function and activities of daily life in older adults with dementia or mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2023; 104: 2092-2108.

8. Gates NJ, Vernooij RW, Di Nisio M, et al. Computerised cognitive training for preventing dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019; 3: CD012279.

9. Salzman T, Sarquis-Adamson Y, Son S, Montero-Odasso M, Fraser S. Associations of multidomain interventions with improvements in cognition in mild cognitive impairment. JAMA Netw Open 2022; 5: e226744.

10. Carter C, James T, Higgs P, Cooper C, Rapaport P. Understanding the subjective experiences of memory concern and MCI diagnosis: a scoping review. Dementia (London) 2023; 22: 439-474.

11. Ma J, Zhang H, Li Z. ‘Redeemed’ or ‘isolated’: a systematic review of the experiences of older adults receiving a mild cognitive impairment diagnosis. Geriatr Nurs 2023; 49: 57-64.

12. Woodward M, Brodaty H, McCabe M, et al. Nationally informed recommendations on approaching the detection, assessment, and management of mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 2022; 89: 803-809.

13. Diamond K, Mowszowski L, Cockayne N, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a healthy brain ageing cognitive training program: effects on memory, mood, and sleep. In Adv Alzheimers Dis 2015; 4: 355-365.

14. Burckhardt M, Watzke S, Wienke A, Langer G, Fink A. Souvenaid for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 12: CD011679.

15. Hevink M, Linden I, De Vugt M, et al. Moving forward with dementia: an explorative cross-country qualitative study into post-diagnostic experiences. Aging Ment Health 2024; 1-10.

16. Swaffer K. Dementia and prescribed dis-engagement. Dementia 2015; 14: 3-6.

17. Alothman D, Card T, Lewis S, Tyrrell E, Fogarty AW, Marshall CR. Risk of suicide after dementia diagnosis. JAMA Neurol 2022; 79: 1148.

18. Armstrong MJ, Bedenfield N, Rosselli M, et al. Best practices for communicating a diagnosis of dementia: results of a multi-stakeholder modified delphi consensus process. Neurol Clin Pract 2024; 14: e200223.

19. Azarias E, Thillainadesan J, Hanger C, et al. Hospital and out-of-hospital services provided by public geriatric medicine departments in Australia and New Zealand. Australas J Ageing 2024; e-pub (https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.13331).

20. Naismith SL, Michaelian JC, Low L-F, et al. Characterising Australian memory clinics: current practice and service needs informing national service guidelines. BMC Geriatr 2022; 22: 578.

21. Pavković S, Goldberg LR, Farrow M, et al. Enhancing post-diagnostic care in Australian memory clinics: health professionals’ insights into current practices, barriers and facilitators, and desirable support. Dementia 2024; 23: 109-131.

22. Laver K, Cumming RG, Dyer SM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for dementia in Australia. Med J Aust 2016; 204: 191-193.

23. Salmon DP, Bondi MW. Neuropsychological assessment of dementia. Annu Rev Psychol 2009; 60: 257-282.

24. Knight R, Khondoker M, Magill N, Stewart R, Landau S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in treating the cognitive symptoms of dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2018; 45: 131-151.

25. Matsunaga S, Fujishiro H, Takechi H. Efficacy and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors for mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 2019; 71: 513-523.

26. Bahar-Fuchs A, Martyr A, Goh AM, Sabates J, Clare L. Cognitive training for people with mild to moderate dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019; 3: CD013069.

27. Woods B, Rai HK, Elliott E, Aguirre E, Orrell M, Spector A; Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group. Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2023; 1: CD005562.

28. Law CK, Lam FM, Chung RC, Pang MY. Physical exercise attenuates cognitive decline and reduces behavioural problems in people with mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review. J Physiother 2020; 66: 9-18.

29. Huang X, Zhao X, Li B, Cai Y, Zhang S, Wan Q, Yu F. Comparative efficacy of various exercise interventions on cognitive function in patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Sport Health Sci 2022; 11: 212-223.

30. Li Z, Guo H, Liu X. What exercise strategies are best for people with cognitive impairment and dementia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2024; 124: 105450.

31. Bennett C, Allen F, Hodge S, Logan P. An investigation of reablement or restorative homecare interventions and outcome effects: a systematic review of randomised control trials. Health Soc Care Community 2022; 30: e6586-e6600.

32. Laver K, Dyer S, Whitehead C, Clemson L, Crotty M. Interventions to delay functional decline in people with dementia: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e010767.

33. Rahja M, Laver K, Whitehead C, Pietsch A, Oliver E, Crotty M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of reablement interventions for people in permanent residential aged care homes. Age Ageing 2022; 51: afac208.

34. De Oliveira EA, Correa UAC, Sampaio NR, Pereira DS, Assis MG, Pereira LSM. Physical exercise on physical and cognitive function in institutionalized older adults with dementia: a systematic review. Ageing Int 2024; 49: 700-719.

35. Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hodgson N, Hauck WW. A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers. JAMA 2010; 304: 983.

36. Clemson L, Laver K, Rahja M, et al. Implementing a reablement intervention, "care of people with dementia in their environments (COPE)": a hybrid implementation-effectiveness study. Gerontologist 2021; 61: 965-976.

37. Leung DKY, Chan WC, Spector A, Wong GHY. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and apathy symptoms across dementia stages: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr 2021; 36: 1330-1344.

38. Mo M, Zacarias-Pons L, Hoang MT, et al. Psychiatric disorders before and after dementia diagnosis. JAMA Network Open 2023; 6: e2338080.

39. González-Martín AM, Almazán AA, Campo YR, Sobrino NR, Caballero YC. Addressing depression in older adults with Alzheimer’s through cognitive behavioral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Aging Neurosci 2023; 15: 1222197.

40. Costello H, Roiser JP, Howard R. Antidepressant medications in dementia: evidence and potential mechanisms of treatment-resistance. Psych Med 2023; 53: 654-667.

41. Burley CV, Casey A-N, Chenoweth L, Brodaty H. Reconceptualising behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: views of people living with dementia and families/care partners. Front Psychiatr 2021; 12: 710703.

42. Bell S, Bhat R, Brennan S, et al.; Guideline Development Group. Clinical practice guidelines for the appropriate use of psychotropic medications in people living with dementia and in residential aged care. Parkville: Monash University; 2022. Available online at: https://www.monash.edu/mips/themes/medicine-safety/major-projects-clinical-trials/clinical-practice-guidelines-for-the-appropriate-use-of-psychotropic-medications (accessed October 2024).

43. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Part A. Short-term pharmacotherapy management of severe BPSD. In: RACGP Aged Care Clinical Guide (Silver Book). 5th ed. Melbourne: RACGP; 2020.

44. Pagone G, Briggs L. Final report: care, dignity and respect. Barton: Royal Commissions; 2021. Available online at: https://www.royalcommission.gov.au/aged-care/final-report (accessed October 2024).

45. Guthrie B, Payne K, Alderson P, McMurdo MET, Mercer SW. Adapting clinical guidelines to take account of multimorbidity. BMJ 2012; 345: e6341-e6341.

46. Kurrle S. Chapter 12 - Physical comorbidities of dementia: recognition and rehabilitation. In: Low L-F, Laver K, eds. Dementia rehabilitation. Academic Press 2021; 213-225.

47. Zhang W, Low L-F, Schwenk M, Mills N, Josephine, Clemson L. Review of gait, cognition, and fall risks with implications for fall prevention in older adults with dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2019; 48: 17-29.

48. Bergman H, Borson S, Jessen F, et al. Dementia and comorbidities in primary care: a scoping review. BMC Prim Care 2023; 24: 277.

49. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Assessing and managing comorbidities. In: Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. Manchester: NICE; 2018. Available online at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97 (accessed October 2024).

50. Picton LJ, George J, Bell JS, Ilomaki JS. Diabetes treatment deintensification in Australians with dementia compared to the general population: a national cohort study. J Am Geriatr Society 2023; 71: 2506-2519.

51. Atoyebi O, Eng J J, Routhier F, Bird M-L, Mortenson WB. A systematic review of systematic reviews of needs of family caregivers of older adults with dementia. Eur J Ageing 2022; 19: 381-396.

52. Dickinson C, Dow J, Gibson G, Hayes L, Robalino S, Robinson L. Psychosocial intervention for carers of people with dementia: what components are most effective and when? A systematic review of systematic reviews. Int Psychogeriatr 2017; 29: 31-43.

53. Bernstein A, Harrison KL, Dulaney S, et al. The role of care navigators working with people with dementia and their caregivers. J Alzheimers Dis 2019; 71: 45-55.