Acute Achilles tendon rupture: diagnosis and management

The Achilles tendon is the largest and strongest tendon in the body. The potential implications of an acute rupture are significant, so timely diagnosis and management are important.

- An acute Achilles tendon rupture (ATR) is typically a low-energy injury. It is generally seen in people aged in their third, fourth or fifth decade of life, who may be undertaking sporadic sporting activities.

- The diagnosis of an acute ATR is primarily clinical, supported by imaging as required.

- Management of an acute ATR requires a multidisciplinary team involving physiotherapists, exercise physiologists, local physicians and orthopaedic surgeons.

- Decisions regarding the approach to management of an acute ATR (conservative or surgical) should be made after consideration of all the risks and benefits.

- Success of management for an acute ATR is highly dependent on early diagnosis, prompt immobilisation in plantarflexion and patient compliance with an agreed protocol. All patients need to be made aware that poor outcomes can have significant implications and life-changing results.

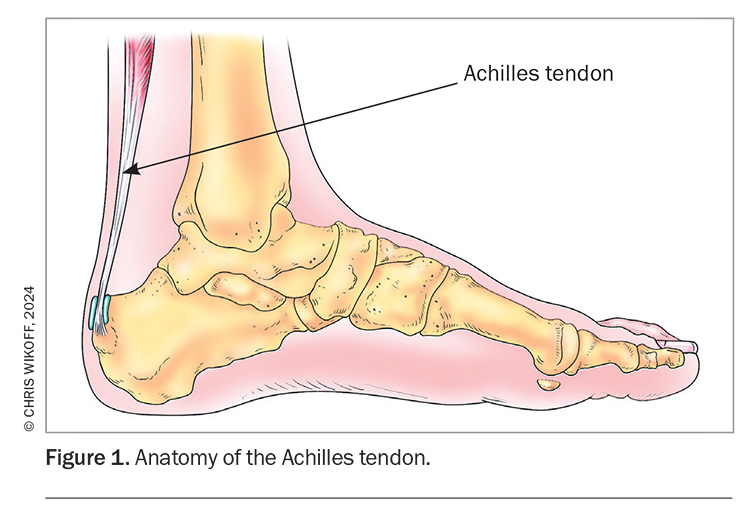

The Achilles tendon, the conjoined tendon of the gastro-cnemius and soleus muscles, is the largest and strongest tendon in the body (Figure 1).1 It is also the most common tendon to be ruptured in the lower leg. An acute Achilles tendon rupture (ATR) is typically a low-energy injury. It is generally seen in people aged in their third, fourth or fifth decade of life, who may be undertaking sporadic sporting activities that involve running; the so-called ‘weekend warriors’.2,3 The potential implications of the injury are significant, so timely diagnosis and management are important.

An acute ATR should be differentiated from rupture resulting from chronic degeneration of the tendon, which commonly occur in the older population (i.e. over 65 years of age). These ruptures typically result from a non-sporting, low-energy injury, with symptoms occurring after more innocuous activities, such as climbing stairs. This type of rupture is not covered further in this article.

History

Taking a careful history is important for a patient presenting with pain around the Achilles tendon. It is helpful to begin by asking about the mechanism of injury. ATR is characterised by a sudden onset of pain, often during the start of a sprint. Patients describe starting to run and then feeling that ‘someone had kicked’ the back of their heel, sometimes adding that they ‘turned around but no one was there’. Other patients report hearing ‘a crack’. Often they recall difficulty walking and feeling that they had ‘done something’ to the ankle. These patients may have played sports in their youth, taken a break and are now aiming to get back into sport. After a long hiatus, it is more common for the injury to occur in the second or subsequent games rather than the first.

Patients often localise the pain to the site of rupture. Often the pain settles after a few days and is not a major symptom. If they have not sought immediate treatment and have been walking with a ruptured Achilles tendon then they may complain of fatigue around the calf.

The history-taking should be completed by asking other relevant questions (e.g. enquiry about previous deep vein thrombosis [DVT]) and to determine contraindications to any analgesia. Smoking, diabetes and peripheral vascular disease are important risk factors for poor outcomes and should be asked for explicitly.

Examination

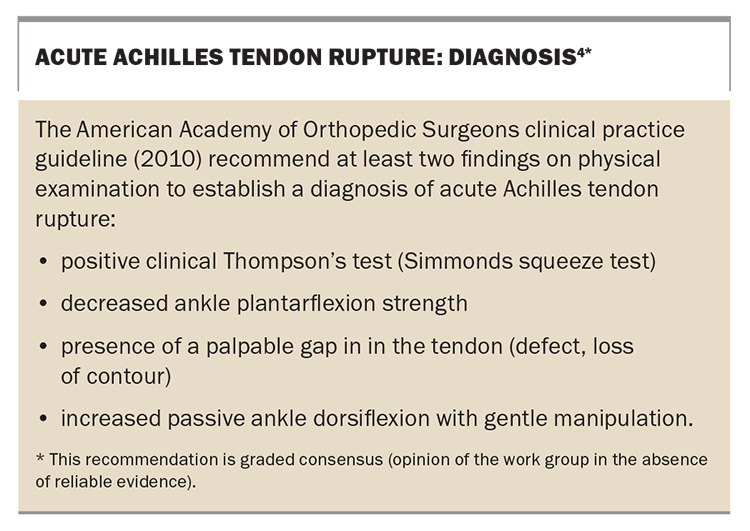

The diagnosis of acute ATR on the basis of examination findings is discussed in the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guideline on Treatment of Achilles Tendon Rupture (Box).4 This consensus-based document provides useful recommendations rather than definite rules for diagnosis; if there is any doubt then imaging should be performed.

A careful and thorough examination is required for a patient who presents with a suspected ATR, which should include the calf, the tendon itself and the ankle. Comparing examination findings with those for the opposite ankle will help to localise the site of the injury and identify abnormalities.

Initial observations begin when the patient arrives and will include footwear (normal shoes, a cast or boot) and whether he or she has walked in weight-bearing or not. Swelling and bruising should be noted (Figure 2).

The remainder of the examination is performed with the patient in the prone position on the examination table, with ankles off the table to allow dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the foot. The resting position of both feet should be assessed. A foot with an intact Achilles tendon will often be held in a slightly plantarflexed position; if the tendon is ruptured then the foot will usually be plantargrade (or less plantarflexed compared with the other ankle).

Careful palpation to assess tenderness at specific locations around the Achilles tendon and heel is important. Often there is not much pain. Pain located around the Achilles insertion may be a sign of a very distal rupture or of insertional Achilles tendonitis.

Often a palpable defect is present in the tendon, which may allow the location of the rupture (proximal, middle or distal) to be delineated. Asking the patient to plantarflex the foot against gentle resistance may indicate whether the rupture is complete or partial. However, if the plantaris is intact a patient may have some plantarflexion of the foot, even if the rupture is complete.

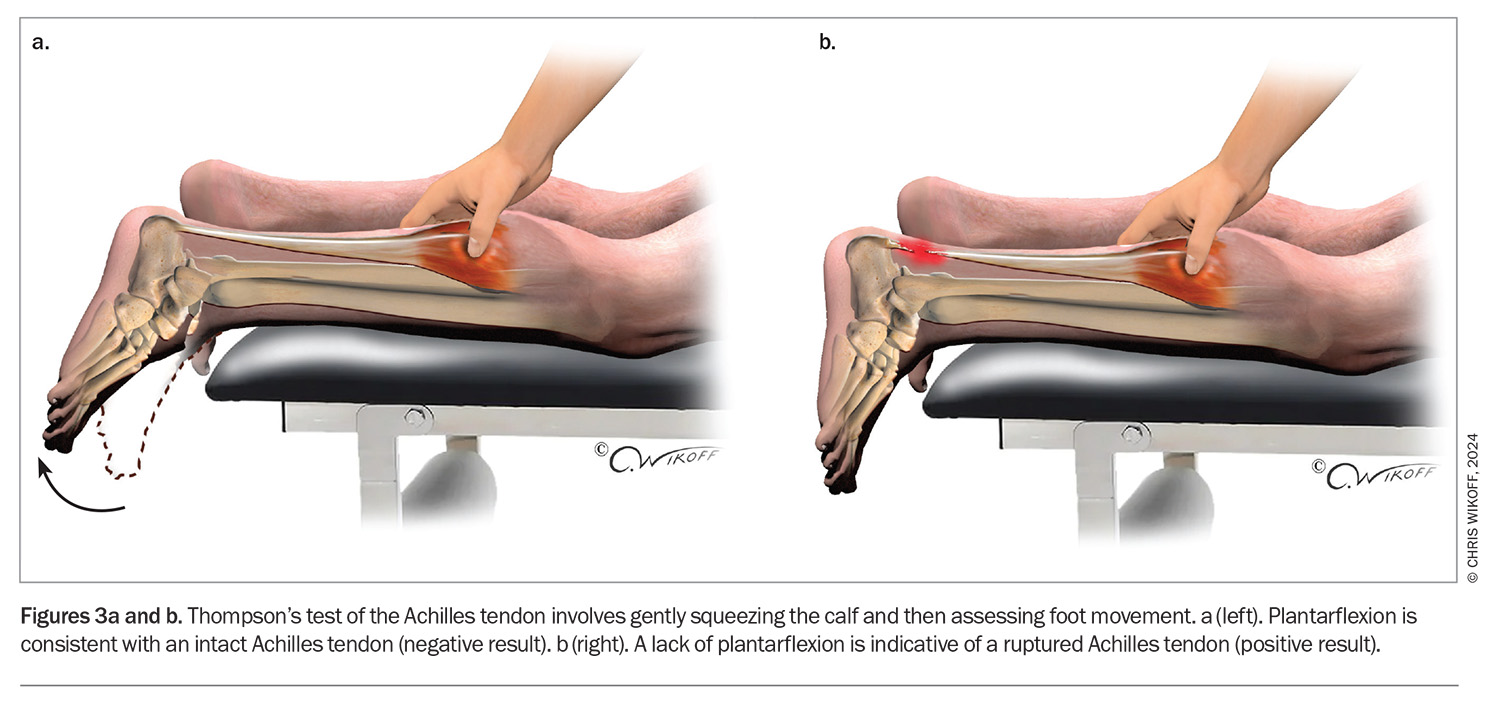

Thompson’s test (Simmonds squeeze test) is a useful clinical test of ATR that should be performed (Figure 3). To perform the test, the examiner squeezes the calf to contract the Achilles tendon: the foot will plantarflex if the tendon is intact (negative test), whereas a foot that does not plantarflex is suspicious for rupture (positive test).

The examination should be completed with an assessment of the calf for DVT and a neurovascular evaluation.

Imaging

Imaging is not required for most patients who present with a suspected ATR but should be arranged if needed. Nonweight-bearing ankle x-rays should be performed is there is concern for an avulsion fracture of the calcaneus. An ultrasound is not usually indicated but may be obtained if the diagnosis is uncertain. An MRI is rarely required but may be performed – for example, to localise a proximal rupture, as tears around the musculotendinous junctions may not be suitable for surgical intervention.

Management

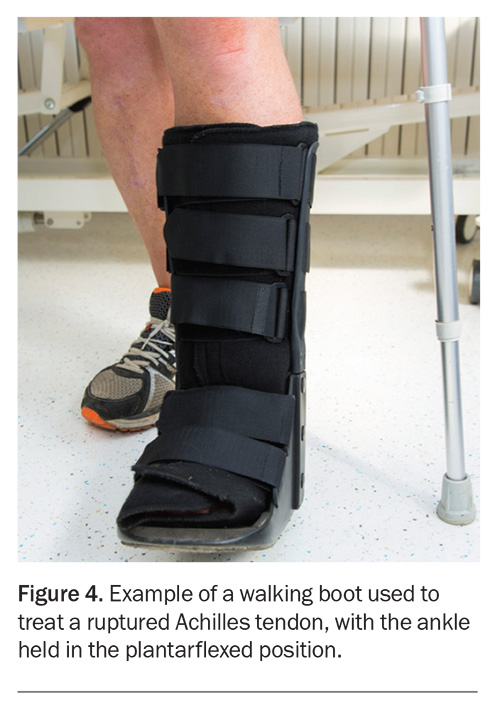

Initial management of all patients with a suspected acute ATR involves immobilising the ankle in an equinus cast in a plantarflexed position as soon as possible and avoidance of weight-bearing (Figure 4).4 To minimise the risk of DVT, all patients should be prescribed short-acting prophylactic medication (e.g. low molecular weight heparin). For a patient with a particularly high risk of DVT, an ultrasound may be performed prior to stopping the prophylaxis.

There is ongoing controversy regarding the optimal approach to management – conservative or surgical – of an acute ATR. In 2019, a systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that surgical treatment has a reduced risk of re-rupture but higher risk of complications than nonsurgical treatment.5,6 More recently, the results of a trial involving 526 patients who were randomised to three groups (nonsurgical treatment, open repair or minimally invasive surgery) showed similar functional outcomes among the three groups.7 However, re-rupture rates were higher for patients in the nonsurgical group than in the other groups (6.2% vs 0.6% in each); in addition, the rate of nerve injury was higher in the minimally invasive surgery group than in the open repair surgery group (5.2% vs 2.8%).7 For athletes, it has been argued that surgical treatment may be preferred to improve performance and reduce the duration to return to play, despite the associated risks.8

The management of an acute ATR requires an experienced multidisciplinary team, which may include physiotherapists, exercise physiologists, local physicians and orthopaedic surgeons. A patient’s decision to manage an acute ATR nonsurgically can be made in consultation with the GP, provided that the appropriate alternatives and the risks and benefits are discussed. Occasionally, a patient presents who has previously ruptured the Achilles tendon in the other ankle – canvassing treatment for the previous episode can be useful because the patient may or may not want to be treated in a similar way. If there is any residual doubt about treatment or if a patient prefers to undergo surgery then referral to an orthopaedic surgeon should be arranged.

The success of management, whether conservative or surgical, will be highly dependent on patient compliance with an agreed protocol, and all patients need to be made aware that poor outcomes can have significant implications and life-changing results.

Conservative management

The conservative management of ATR involves placing the ankle in a plantar-flexed backslab/frontslab plaster cast as soon as possible (ideally within 24 or 48 hours from the time of injury), and keeping the patient nonweight-bearing for a minimum of two weeks. Following this, a patient may be placed in a foot and ankle orthosis or another below-knee cast with the foot in plantarflexion (Figure 4). The ideal orthosis allows for plantarflexion of the orthosis itself. Using heel wedges, while acceptable, may result in plantarflexion at the midfoot rather than the hindfoot. Members of the treating team collaborate to discuss the timing of physiotherapy, changes in weight-bearing status and other aspects of management. Examples of common functional rehabilitation protocols have been described in the literature.7,9

Surgical management

Both open and minimally invasive surgical methods are used for Achilles tendon repair, which often involves the patient placed in a prone position for the procedure. The open approach involves an incision along the Achilles tendon, which is usually placed slightly medially to the tendon rather than laterally (to avoid risk of injury to the sural nerve) and not directly posteriorly (to reduce the likelihood that the scar will interfere with footwear). The paratenon is then incised, elevated and protected, as this will be used during closure. The length of the incision includes the rupture (area of interest) and should be long enough to expose enough normal tendon to allow suture placement. The foot is placed in appropriate equinus (comparable to the other foot) and the tendon repaired with the appropriate tension using various sutures and techniques. It is preferable to err for more plantarflexion because the muscle–tendon complex tends to lengthen with time. Minimally invasive repair is performed with the aid of various jigs or guides and sutures according to the specific operating technique. Although the incision is smaller, there is an increased risk of injury to the sural nerve.

There is no published recommendation regarding the choice of the open or minimally invasive surgical method for Achilles tendon repair in most patients and the choice that is made will depend on various factors, including patient preference on the length of incision and the risk of sural nerve injury. However, in patients with a longstanding ATR (diagnosed more than 10 days after the injury) open surgery is generally performed; this can be combined with various other adjuncts that may involve a tendon transfer or Achilles tendon reconstruction or muscle belly lengthening.

Conclusion

Acute rupture of the Achilles tendon is a common injury that is generally seen in the ‘weekend warrior’ population. The diagnosis is primarily clinical, supported by imaging as required. Prompt immobilisation in an equinus cast is paramount. Both conservative and nonsurgical approaches to management are used. Referral to an orthopaedic surgeon should be arranged for patients who wish to be treated surgically and for those who are unsure about their management preferences. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. O’Brien M. The anatomy of the Achilles tendon. Foot Ankle Clin 2005; 10: 225-238.

2. Shamrock AG, Dreyer MA, Varacallo M. Achilles tendon rupture. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL); StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

3. Holm C, Kjaer M, Eliasson P. Achilles tendon rupture – treatment and complications: a systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2015; 25: e1-e10.

4. Chiodo CP, Glazebrook M, Bluman EM, et al. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on treatment of Achilles tendon rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92: 2466-2468.

5. Lantto I, Heikkinen J, Flinkkila T, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing surgical and nonsurgical treatments of acute Achilles tendon ruptures. Am J Sports Med 2016; 44: 2406-2414.

6. Ochen Y, Beks RB, van Heijl M, et al. Operative treatment versus nonoperative treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2019; 364: k5120.

7. Myhrvold SB, Brouwer EF, Andresen TKM, et al. Nonoperative or surgical treatment of acute Achilles’ tendon rupture. N Engl J Med 2022; 386: 1409-1420.

8. Mansfield K, Dopke K, Koroneos Z, Bonaddio V, Adeyemo A, Aynardi M. Achilles tendon ruptures and repair in athletes – a review of sports-related Achilles injuries and return to play. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2022; 15: 353-361.

9. Willits K, Amendola A, Bryant D, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: a multicenter randomized trial using accelerated functional rehabilitation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92: 2767-2775.