Large hiatus hernias – more than just reflux

Symptomatic large hiatus hernias are a common presentation in general practice as the population ages and becomes more overweight. The clinical features range from those of chronic gastric entrapment and debilitating cardiorespiratory symptoms to a surgical emergency. Surgery is often indicated and markedly improves quality of life.

- The diagnosis of a large hiatus hernia (LHH) is difficult because of the nonspecific symptoms caused by the posterior mediastinal mass effect of the large hiatus hernia within the chest.

- LHHs often present with symptoms of obstruction or entrapment, which are not typical of reflux disease. These include dysphagia, early satiety, bloating, chest pain and pulmonary symptoms. Iron-deficiency anaemia may also be a feature.

- LHHs may cause symptoms resulting from physiological compromise of the cardiorespiratory system, such as dyspnoea, lethargy and palpitations.

- LHHs may present acutely with life-threatening complications, mimicking cardiac syndromes (chest pain, hypotension), vomiting or haematemesis and melaena.

- Endoscopy has low sensitivity for assessing the size of a hiatus hernia, only demonstrating elevation of the gastro-oesophageal junction and not a potentially dangerous paraoesophageal hernia. Cross-sectional imaging is preferable (barium meal, CT on a full stomach).

- Expert laparoscopic surgery is well tolerated with low morbidity and mortality, reduces the risk of acute gastric entrapment and has a high level of patient satisfaction and quality-of-life improvement.

Large hiatus hernias (LHHs), where more than 30% of the stomach is herniated into the chest cavity, was once considered to be a relatively rare disease, but as the general population ages, LHH appears to be causing an increasing burden of disease. More than 3% of patients presenting to general practice are likely to have an undiagnosed, potentially life-threatening LHH based on conventional assessment. These figures may understate the true prevalence, as recognising LHH is difficult because the symptoms are often nonspecific, and endoscopy is not sensitive to the degree of anatomical abnormality. Mediastinal space-occupying symptoms of LHH may cause physiological symptoms that are frequently attributed to other systems, especially the cardiorespiratory system. Entrapment can mimic cardiac ischaemia or cause complete or partial obstruction or acute gastric strangulation, requiring urgent patient care in hospital. This article discusses the condition of LHH, associated symptoms and the best methods for diagnosis and outlines the management options.

Pathophysiology

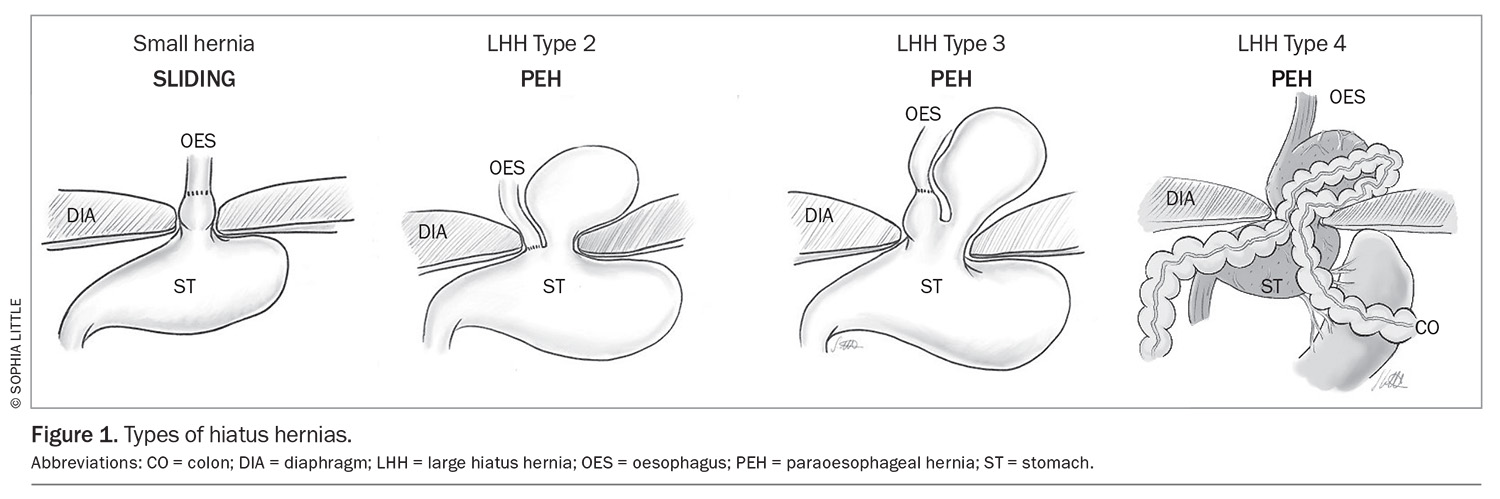

An LHH may be defined by more than 30% of the stomach (or occasionally other organ[s]) passing through the diaphragmatic hiatus (Figure 1). It may present as different types, with types 2 and 3 being paraoesophageal hernias (PEHs) and type 4 being PEHs involving another organ (usually the colon) also herniated into the chest. LHHs are more common among individuals aged older than 60 years, and there is often a female preponderance.1 Patients are frequently overweight.1

The prevalence of LHH has been greatly under-reported historically at about 5% of all hiatus hernias (HHs). It is said that any HH occurs in about 60% of patients older than 60 years of age. However, an unselected study including patients with atherosclerosis found that the prevalence of LHH was 93 of 3179 (3%) among an unselected population who had large or small HHs, based on CT imaging data.2 The true prevalence remains an estimate.

A PEH is defined by the stomach rising above the gastro-oesophageal junction, such that the stomach is inherently twisted. This leads to a number of potential structural problems that may appear as an acute catastrophic event or a chronic debilitating condition.

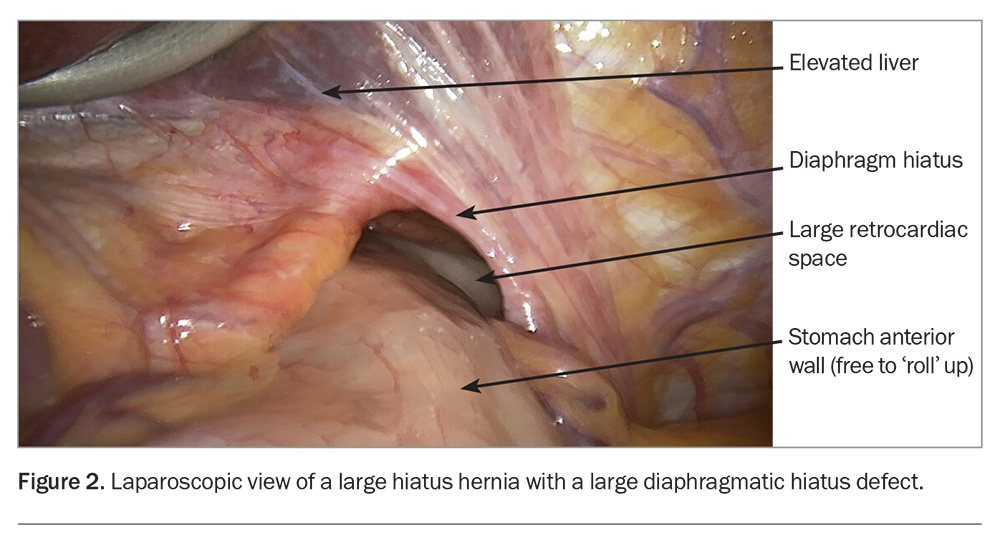

The larger dislocation of the gastro-oesophageal junction causes twisting (‘rolling’) of the upper stomach. Patients with this condition often present with multiple symptoms suggesting an LHH or typical reflux symptoms associated with a sliding HH (Box 1).3 The posterior stomach is more firmly attached to retroperitoneal structures, but the anterior aspect of the stomach is free. The ‘rolling’ phenomenon occurs when the anterior wall of the stomach twists into the chest (Figure 2) and may become entrapped. The mass effect of the stomach in the mediastinum may cause physiological compromise by impeding cardiac return and causing pulmonary compression, and is associated with pulmonary microaspiration; these effects may result in dyspnoea, the most frequently occurring symptom.4,5 Anaemia is common, caused by episodes of mucosal ischaemia and ulceration (Cameron’s ulcers are associated with the diaphragmatic opening causing pressure necrosis of the mucosa).6 Entrapment gastropathy and gastric venous hypertension may also result in blood loss.

Symptomatology

Symptoms may be grouped into those associated with reflux, those caused by entrapment of the hernia’s contents and those associated with physiological compromise. Symptoms may present in a chronic fashion or acutely.

Chronic presentation of symptoms

The twisting nature of an LHH or PEH explains the symptoms that may arise from entrapment and obstruction of the stomach. The stomach may assume a chronic volvulus position with early satiety, bloating, chest and epigastric pain after eating, sudden uncontrolled eructation (decompression of the stomach) or dysphagia (by angulation of the gastro-oesophageal junction). Reflux symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation are less frequent (Box 1). Dyspnoea on exercise is a frequent physiologically mediated symptom and can be postprandial or can occur during ordinary activity. Patients may complain of vague symptoms of lethargy, weakness, feeling faint after eating and needing to rest. A recent systematic study has demonstrated cardiac-filling abnormalities caused by atrial compression due to the mass effect of the full mediastinal stomach. This is commonly under-reported on CT.4

Patients with any of the symptoms listed in Box 1 should be suspected of having an LHH rather than a simple sliding HH.3 The postprandial nature of symptoms, which are often relieved by belching, is suggestive (e.g. postprandial chest pain or dyspnoea). The stomach in the chest fills quickly (early satiety) and confers a sense of bloating or pressure after eating. These symptoms are usually not volunteered by the patient. Patients frequently consider lethargy and dyspnoea to be a matter of ‘fitness’ or age and do not see them as a new condition.

The most common symptoms are not associated with reflux, tend to be vague or suggest cardiorespiratory disease, which makes diagnosis difficult. Older patients may present with chronic weakness, weight loss and malnutrition because of an inability to achieve adequate nourishment. Iron-deficiency anaemia may be insidious, requiring iron therapy and defeating attempts to find a source of blood loss.6

Acute presentation

A patient with entrapment (incarceration) of the herniated stomach may present with severe postprandial chest and epigastric pain. The desire to vomit and the inability to do so (and the inability to pass a nasogastric tube) together constitute Borchardt’s triad of acute gastric volvulus.7 Acute volvulus is a surgical emergency because of the risk of gastric ischaemia, inhalation, perforation and haemorrhage. LHH may also present with massive aspiration events or pneumonia. Severe anaemia, haematemesis, dysphagia or bolus impaction may cause acute presentation to a GP or the emergency department. Elective surgical management is much safer and more likely to involve laparoscopy rather than laparotomy.8

Diagnosis of large hiatus hernias

Endoscopy

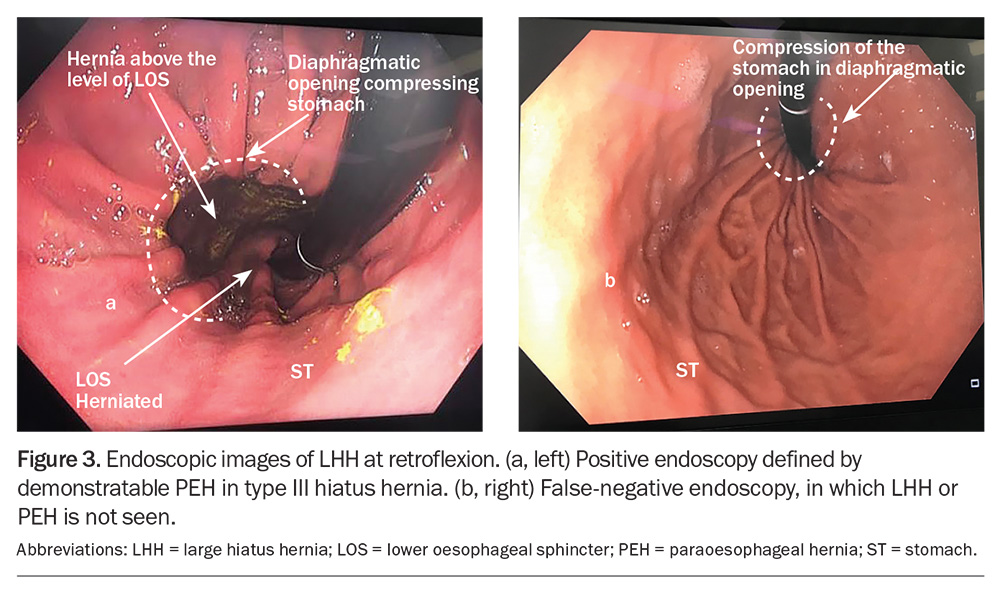

Patients presenting with heartburn and regurgitation often undergo endoscopy, an important part of the workup for suspected LHH (Flowchart). A HH is frequently seen; however, its size is not frequently appreciated, and endoscopy may not identify the rolling component of the stomach, which is outside the field of view of the endoscope (Figure 3).5 Endoscopy, however, is excellent to help identify conditions such as Barrett’s oesophagus, oesophagitis and Cameron’s ulcers in the intrathoracic stomach. Hernias reported greater than 3 cm in size on endoscopy are frequently an LHH or PEH and require cross-sectional imaging.

Medical imaging

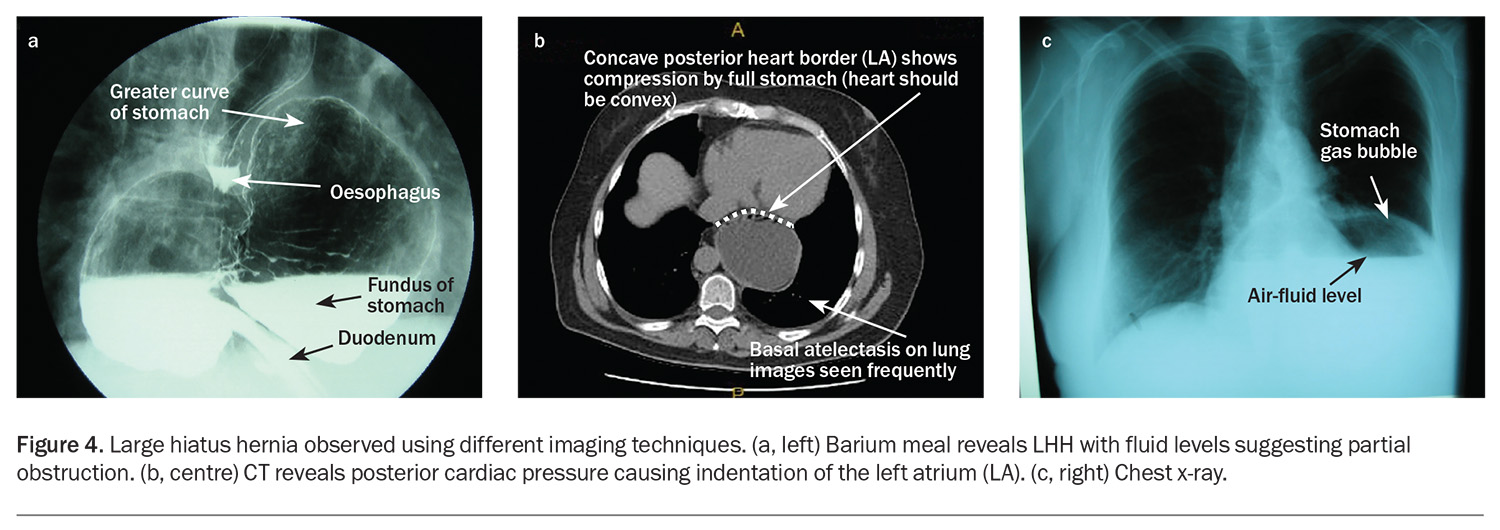

Chest x-ray and double-contrast barium meal or CT scan, especially in the water-filled stomach, is complementary to endoscopy. Chest x-ray with a lateral view often shows a water-filled cavity behind the heart with fluid levels indicating retention of contents within the semi-obstructed stomach (and a risk of pulmonary aspiration) (Figure 4). Radiology reports of the size of the hiatus hernia such as ‘moderate’ are approximate and usually reflect the presence of an LHH or PEH with likely entrapment or physiological consequences. The radiological comment of a ‘sliding’ HH is also approximate. If the hernia is large (>30% of the intrathoracic stomach), a rolling component is often seen at surgery, which is not detected preoperatively.

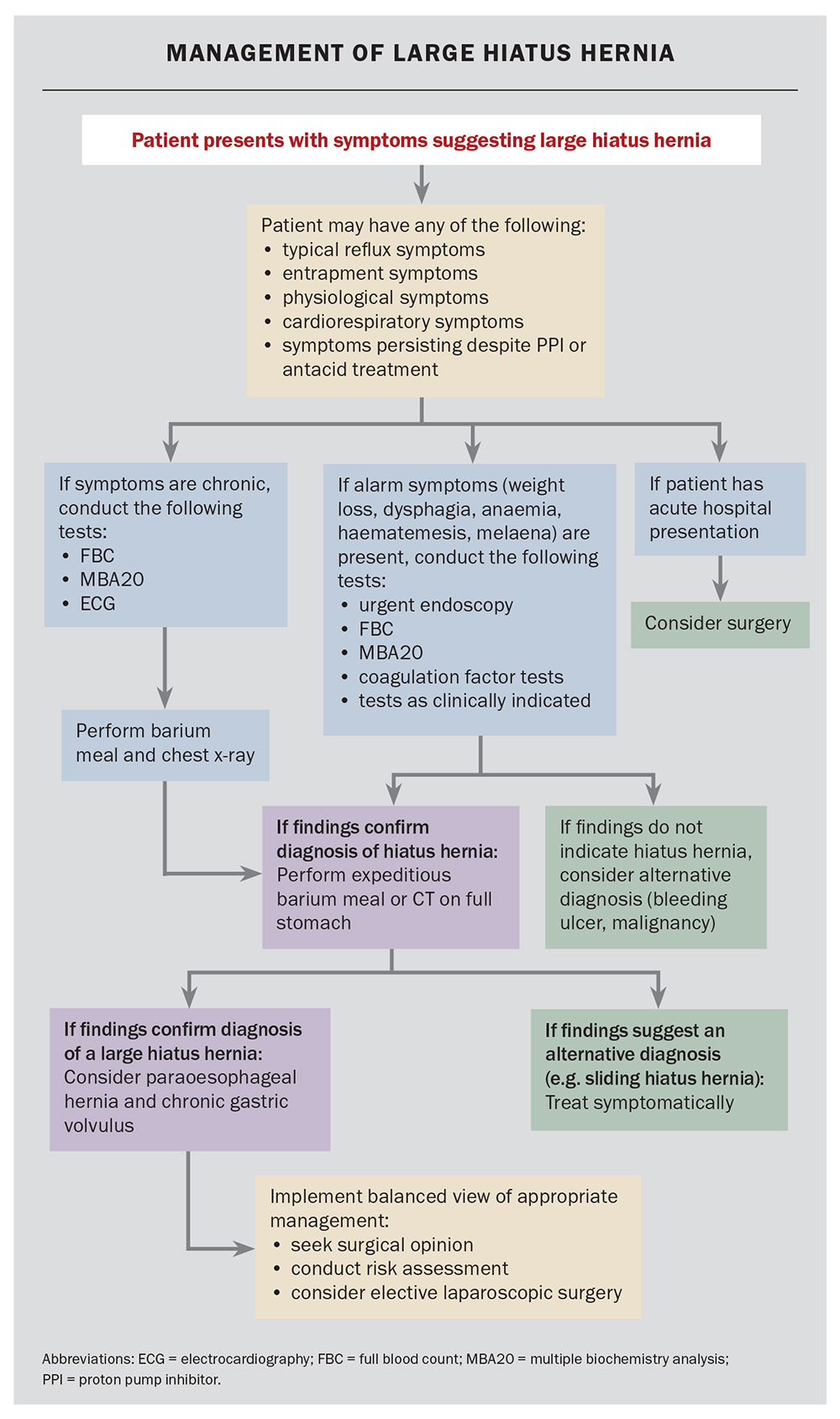

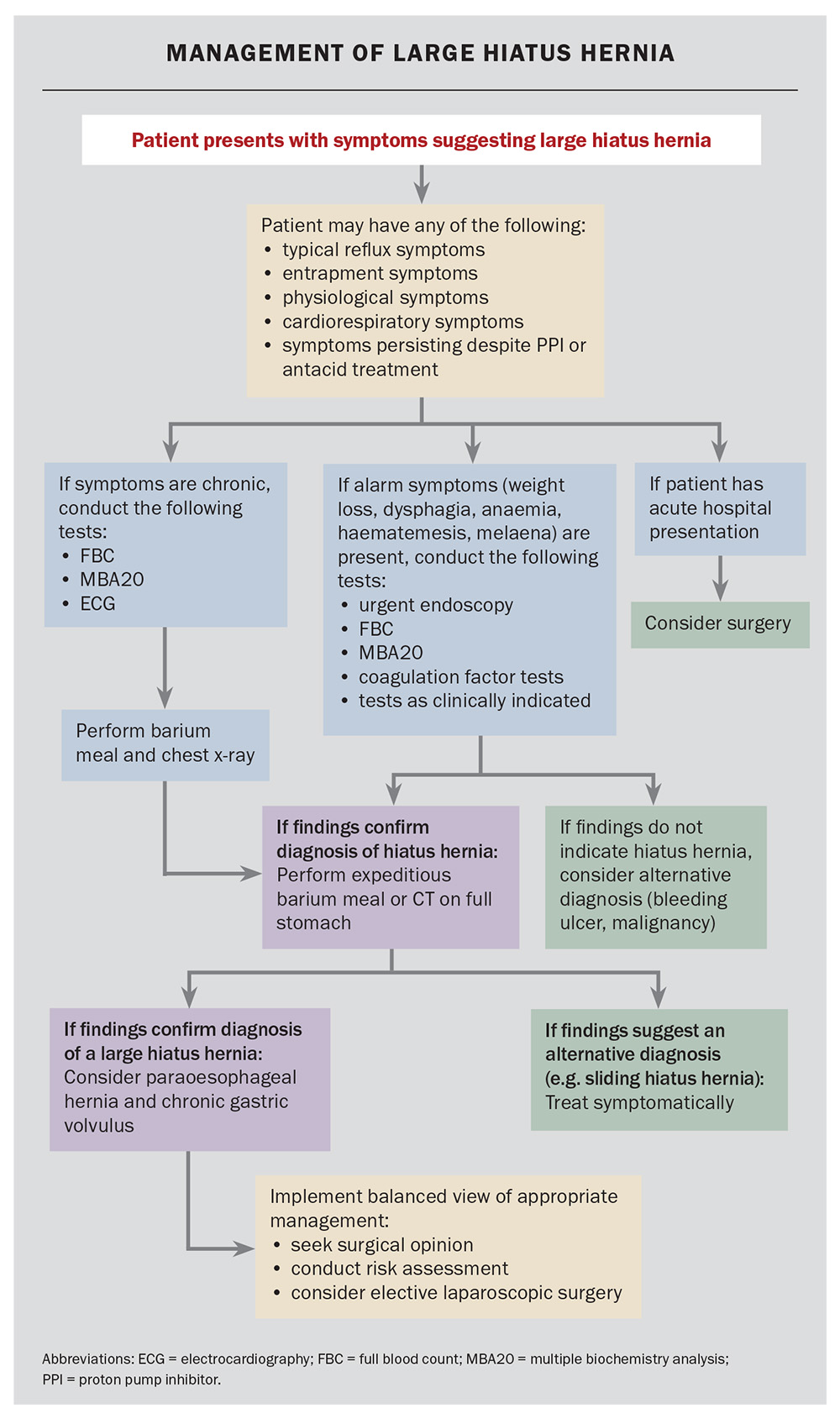

Management of a suspected large hiatus hernia

Patients presenting with chronic symptoms suggestive of an LHH and with alarm symptoms (dysphagia, odynophagia, weight loss, haematemesis, anaemia, early satiety, change in digestive symptoms or new onset) should undergo expeditious endoscopy and double-contrast barium meal to exclude Cameron’s ulcers and alternative diagnoses, such as an ulcer or carcinoma (Flowchart). The size of the HH reported on endoscopy may be imprecise. In the presence of physiological or entrapment symptoms, further investigation is recommended. If dyspnoea is present, cardiorespiratory testing is recommended, but suspicion of LHH should be entertained. Cardiac compression may be readily diagnosed using lateral CT scanning on a full stomach. Recurrent chest infections and nocturnal aspiration may be secondary to silent microaspiration. Dysphagia requires assessment using endoscopy; however, the condition is frequently caused by angulation of the gastro-oesophageal junction and is common in patients with LHH.

Patients without alarm symptoms may proceed to have estimates of haemoglobin levels and biochemistry assessments. If the chest x-ray findings are suspicious or there are any indications of dyspnoea, a CT scan with a water-filled stomach may be helpful. A barium study can delineate the anatomy, as it frequently demonstrates angulation of the oesophagus and rotation of the stomach. Identification of an LHH with or without a paraoesophageal component is an indication for obtaining the advice of an oesophagogastric surgical specialist service. Heartburn may be palliated by proton pump blockade. Iron-deficiency anaemia should be managed using standard protocols. However, if no other cause is found, the presence of an LHH may be the explanation (transient Cameron’s ulceration). Occasionally, during the investigation of other conditions, an LHH will be seen on chest x-ray; these are almost always PEHs and require symptomatic evaluation and an awareness of the potential risks of acute or chronic disease.

Management of a symptomatic large hiatus hernia

Medical management

Acid suppression may be effective in the management of heartburn in patients with symptomatic LHH, but regurgitation and the risk of aspiration or microaspiration will persist. Entrapment symptoms and the risk of volvulus and strangulation are unaltered by medical therapy. Physiological compromise is unchanged, and cardiac compression, air trapping and pulmonary effects causing dyspnoea are most likely to continue.4,9

Laparoscopic surgery

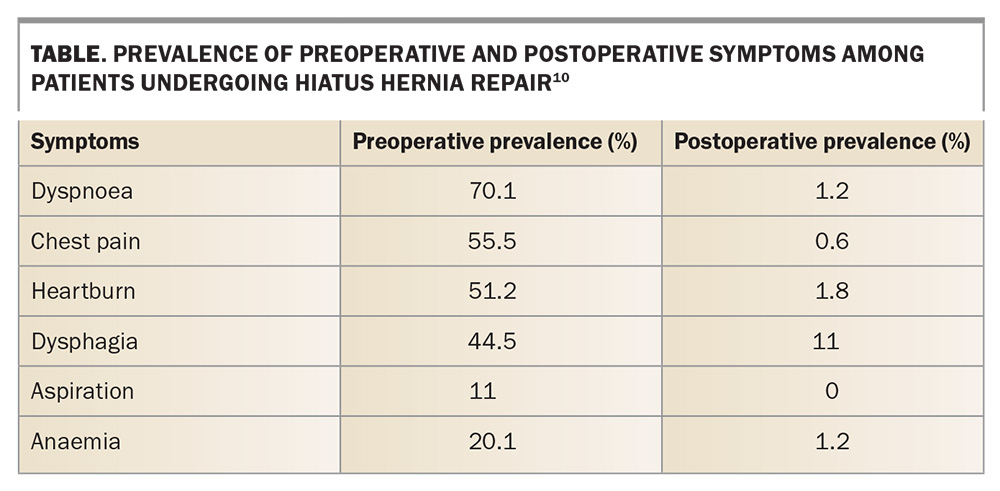

Laporoscopic surgery remains the mainstay of management of symptomatic LHHs by correcting the anatomical defect. There is a substantial improvement in the quality of life, as the symptoms are greatly improved and patient satisfaction levels are high (Table).3,10,11 The risks to gastric integrity by entrapment and strangulation are relieved. No cases of acute gastric complications occurred in a very large series reported following surgical repair.1 The reoperation rates for large recurrences are very low, and although small hernias do occur in up to 25% of patients, they are usually inconsequential.12 Patients aged older than 80 years can undergo surgery with safety (one of 189 patients are reported to die out-of-hospital from myocardial infarction 30 days after surgery).13 The risks of acute gastric strangulation and aspiration are reduced or eliminated by surgery.

Nonsurgical management of symptomatic LHH may have a poor natural history, with one study citing a 16% HH-associated mortality from acute complications within four years.14 The symptoms and size of PEHs progress over time, and LHHs can be expected to worsen.14,15

Assessment for laparoscopic surgery

Patient assessment requires a consideration of the current symptoms and the expected symptomatic decline due to the progression of the HH size and rotation over time. The level of frailty in an older patient cohort and the level of LHH complications previously experienced must be balanced against the high mortality of surgery in the acute setting of LHH strangulation or volvulus, when considering elective repair.

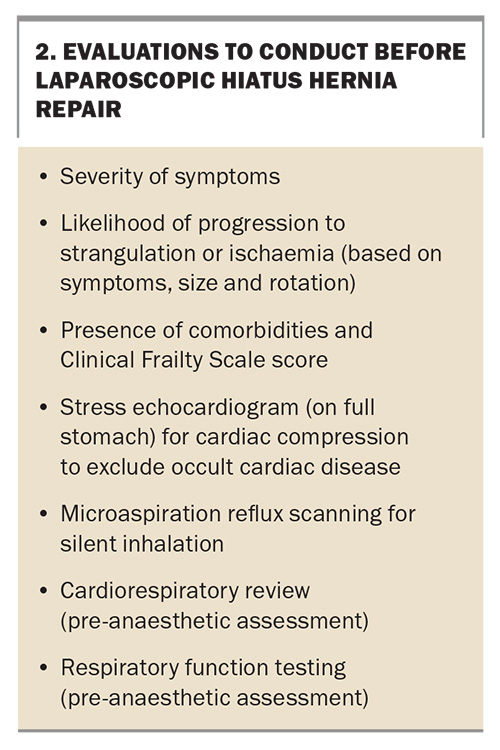

The risk of elective surgery is acceptable in experienced hands, even among older patients. The patient work-up includes endoscopy, cross-sectional imaging, appropriate assessment of fitness and comorbidities and oesophageal manometry as indicated. Respiratory function testing and stress echocardiography are frequently performed as assessment for planned surgery (Box 2).

Surgical course of laparoscopic repair

Surgery is performed via laparoscopy and usually results in a two- to three-day hospital stay (unless there are major comorbidities). A soft diet is consumed for several weeks, and there are minimal requirements for analgesia after the first 48 hours. An antireflux valve is usually formed, so that reflux is better controlled and quality of life is improved.16 Publications reporting these outcomes come from high-volume surgical units.1,10

Management of an asymptomatic large hiatus hernia

After assessment of a patient’s reflux, cardiorespiratory and entrapment symptoms, there are very few patients with LHHs or PEHs who are truly without symptoms. The appropriate management for the infrequent, totally asymptomatic patient is a conundrum and often depends on patient preference, size of the hernia and chronic gastric rotation being a known risk factor for acute complications.

Conclusion

An LHH confers a substantial anatomical risk, and many symptoms cannot be adequately treated medically, nor can the possibility of major acute hernia complications be controlled. Diagnosis is difficult because of the symptoms of entrapment and physiological compromise leading to a confusing clinical scenario. Assessment and ongoing care, along with an appropriate referral strategy, remain the responsibility of the GP. Gastroscopy and cross-sectional imaging are a part of the management algorithm. Symptoms will persist without surgical management, and the risk of major complications remains among patients. Patients’ quality of life is improved by surgery and the surgical risk is low in high-volume centres. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Associate Professor Falk holds a patent on a technique for pulmonary microaspiration. Mrs Cordeschi: None.

References

1. Nguyen CL, Tovmassian D, Isaacs A, Gooley S, Falk GL. Trends in outcomes of 862 giant hiatus hernia repairs over 30 years. Hernia 2023; 27: 1543-1553.

2. Kim J, Hiura GT, Oelsner EC, et al. Hiatal hernia prevalence and natural history on non-contrast CT in

the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2021; 8: e000565.

3. Lee F, Khoma O, Mendu M, Falk G. Does composite repair of giant paraoesophageal hernia improve patient outcomes? ANZ J Surg 2021; 91: 310-315.

4. Naoum C, Falk GL, Ng ACC, et al. Left atrial compression and the mechanism of exercise impairment in patients with a large hiatal hernia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58: 1624-1634.

5. Mugino M, Little SC, van der Wall H, Falk GL. High incidence of dyspnoea and pulmonary aspiration in giant hiatus hernia: a previously unrecognised cause of dyspnoea. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2022; 104: 530-537.

6. Aly A, Munt J, Jamieson GG, Ludemann R, Devitt PG, Watson DI. Laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernias. Br J Surg 2005; 92: 648-653.

7. Borchardt M. Zur pathologie und therapie des magenvolvulus. Arch Klein Chir 1904; 74: 243-260.

8. Fullum TM, Oyetunji TA, Ortega G, et al. Open versus laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair. JSLS 2013; 17: 23-29.

9. Naoum C, Kritharides L, Ing A, Falk GL, Yiannikas J. Changes in lung volumes and gas trapping in patients with large hiatal hernia. Clin Respir J 2017; 11: 139-150.

10. Luketich JD, Nason KS, Christie NA, et al. Outcomes after a decade of laparoscopic giant paraesophageal hernia repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010; 139: 395-404, 404.e1.

11. Le Page PA, Furtado R, Hayward M, et al. Durability of giant hiatus hernia repair in 455 patients over 20 years. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2015; 97: 188-193.

12. Nguyen CL, Tovmassian D, Zhou M, et al. Recurrence in paraesophageal hernia: patient factors and composite surgical repair in 862 cases. J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 27: 2733-2742.

13. Khoma O, Mugino M, Falk GL. Is repairing giant hiatal hernia in patients over 80 worth the risk? Surgeon 2020; 18: 197-201.

14. Sihvo EI, Salo JA, Räsänen JV, Rantanen TK. Fatal complications of adult paraesophageal hernia: a population-based study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009; 137: 419-424.

15. Oude Nijhuis RAB, Hoek MV, Schuitenmaker JM, et al. The natural course of giant paraesophageal hernia and long-term outcomes following conservative management. United European Gastroenterol J 2020; 8: 1163-1173.

16. Müller-Stich BP, Achtstätter V, Diener MK, et al. Repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernias-is a fundoplication needed? A randomized controlled pilot trial. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 221: 602-610.