Hiatus hernia: when to treat

Most hiatus hernias are asymptomatic and do not require treatment; however, patients with symptomatic hiatus hernias can experience gastro-oesophageal reflux and may require lifestyle modification, medical therapy and, in rare cases, surgery.

- A hiatus hernia occurs when intra-abdominal contents are proximally displaced above the diaphragm into the thoracic cavity.

- The most common type is a sliding hiatus hernia, in which the gastro-oesophageal junction slides into the thoracic cavity through the oesophageal hiatus.

- Paraoesophageal hiatus hernias are a less common subtype, and are sometimes idiopathic or sometimes occur as a complication of surgery.

- Hiatus hernias are often incidentally diagnosed on imaging or gastroscopy and do not require dedicated imaging or monitoring.

- Most hiatus hernias are asymptomatic and therefore do not need any specific treatment.

- The most common symptoms of a hiatus hernia relate to the resultant gastro-oesophageal reflux; management therefore mainly comprises of lifestyle modifications or medical therapy, although surgery may be required in rare cases.

Ahiatus hernia occurs when intra-abdominal contents are proximally displaced through an opening (hiatus) above the diaphragm into the thoracic cavity. It is a common condition, with a rising prevalence in our ageing and increasingly overweight population.1,2

In many people, there are no associated symptoms and hiatus hernias are often diagnosed incidentally on chest x-ray, gastroscopy or barium swallow. As such, estimations of prevalence are challenging but have been demonstrated to range between 10 and 50% in western populations and between 2 and 20% in Asian populations.3 When symptomatic, hiatus hernias usually present with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and its sequelae, including oesophagitis, Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Some rarer types of hiatus hernias can present with serious acute complications, such as gastrointestinal ischaemia and gastric volvulus.

Types of hiatus hernias

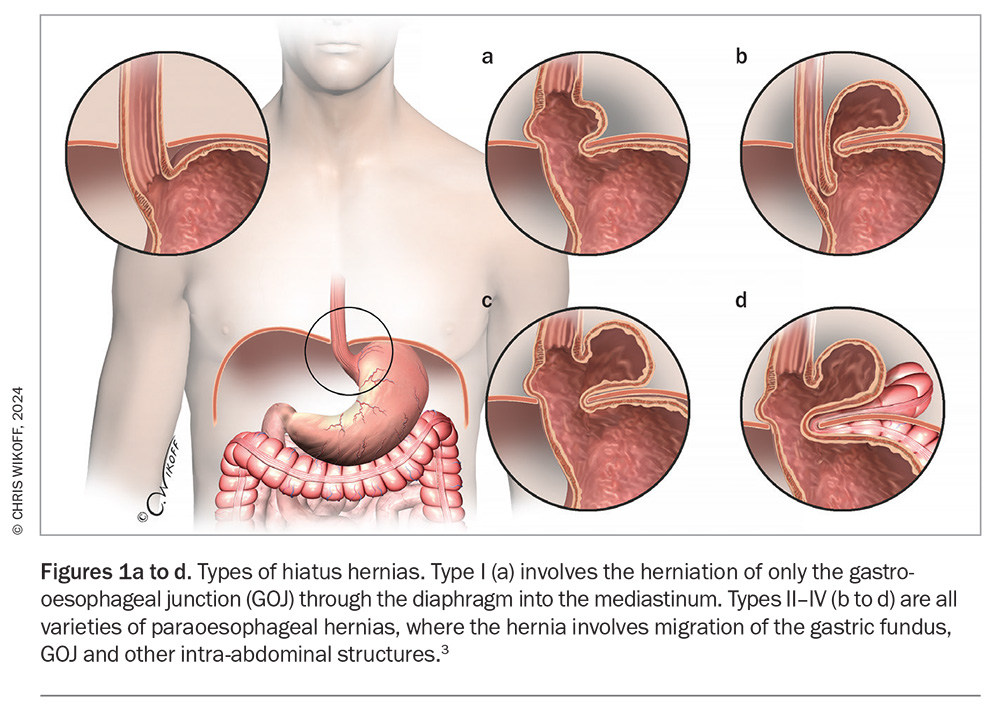

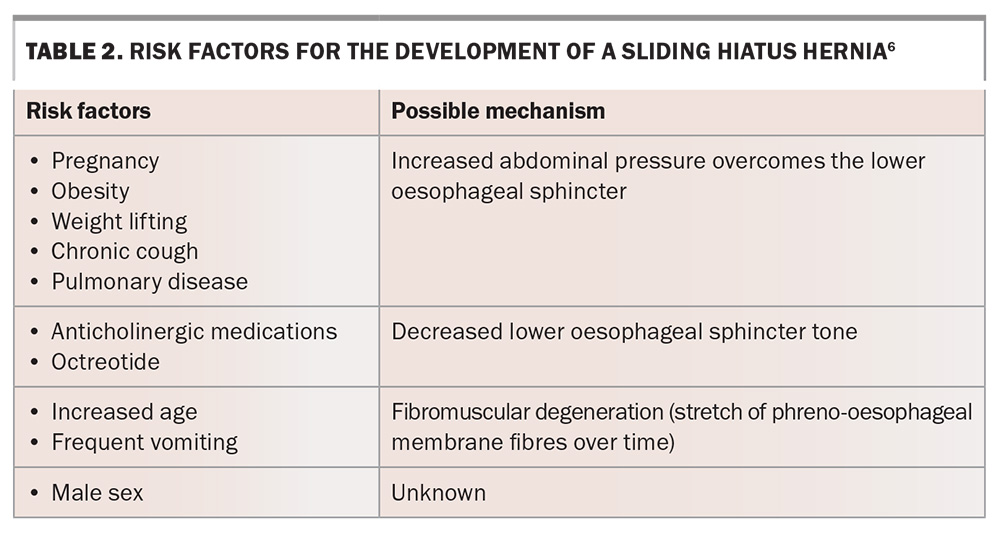

Type I, also known as the sliding hiatus hernia, is the most common type of hiatus hernia, comprising 85 to 95% of all cases. This type refers to the herniation of just the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ) through the diaphragm into the mediastinum (Figure 1, Table 1).

Types II to IV are all varieties of paraoesophageal hernias, which account for the remaining 5 to 15% of hiatus hernias, and refer to hernias that involve migration of the gastric fundus, GOJ and other intra-abdominal structures. The cause of paraoesophageal hernias is largely unknown, although they can arise after damage to the hiatus during surgeries such as bariatric surgery or surgery for GORD. Symptoms arising from paraoesophageal hernias can be nonspecific and range from generalised abdominal discomfort to acute abdominal pain from ischaemia or bowel obstruction as the hiatus enlarges and more organs protrude into the thoracic cavity. Gastric volvulus is a rare complication that occurs in type II paraoesophageal hernias, and occurs due to rotation of the stomach on its axis of fixation at the GOJ. This can lead to acute gastric obstruction, incarceration and perforation. Barium studies with focus on the GOJ help to differentiate between type II and III hernias. Paraoesophageal hernias are more likely to need specialist surgical management and may require urgent surgical intervention if these complications occur. The remainder of this article refers primarily to type I hiatus hernias.

Normal swallowing

The diaphragm is a muscular layer that divides the abdominal contents from the thorax. It is disrupted by a number of openings, made up of muscular fibres (crus), through which vessels, nerves and organs pass. The oesophageal hiatus comprises the right diaphragmatic crus in a sling-like configuration, which creates an oval-shaped opening. The lower part of the oesophagus is anchored to the diaphragm by the phreno-oesophageal membrane, which is formed by the endothoracic and endoabdominal fascia, and inserts circumferentially into the distal end of the oesophagus.

The lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) is a 2.5 to 4.5 cm long noose-shaped smooth muscle structure located at the junction of the oesophagus and stomach, surrounded by the diaphragmatic crus.4 Two key mechanisms that prevent the reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus are the constant tonic contraction of the LOS and the flap valve created by the acute angle of His (between the oesophagus and the gastric cardia).

Swallowing involves the contraction of longitudinal smooth muscle fibres in the oesophagus, shortening the oesophagus. As the oesophagus shortens, the LOS and a small part of the stomach herniate through the oesophageal hiatus in what is known as physiological herniation. The phreno-oesophageal membrane stretches to allow elevation of the distal end of the oesophagus during this process. At the end of swallowing, once the bolus of food or saliva has passed down into the stomach, the muscle fibres of the oesophagus relax, allowing it to lengthen again. Elastic recoil of the phreno-oesophageal membrane returns the distal end of the oesophagus to its resting position, with the GOJ located back below the oesophageal hiatus.

Causes of hiatus hernia

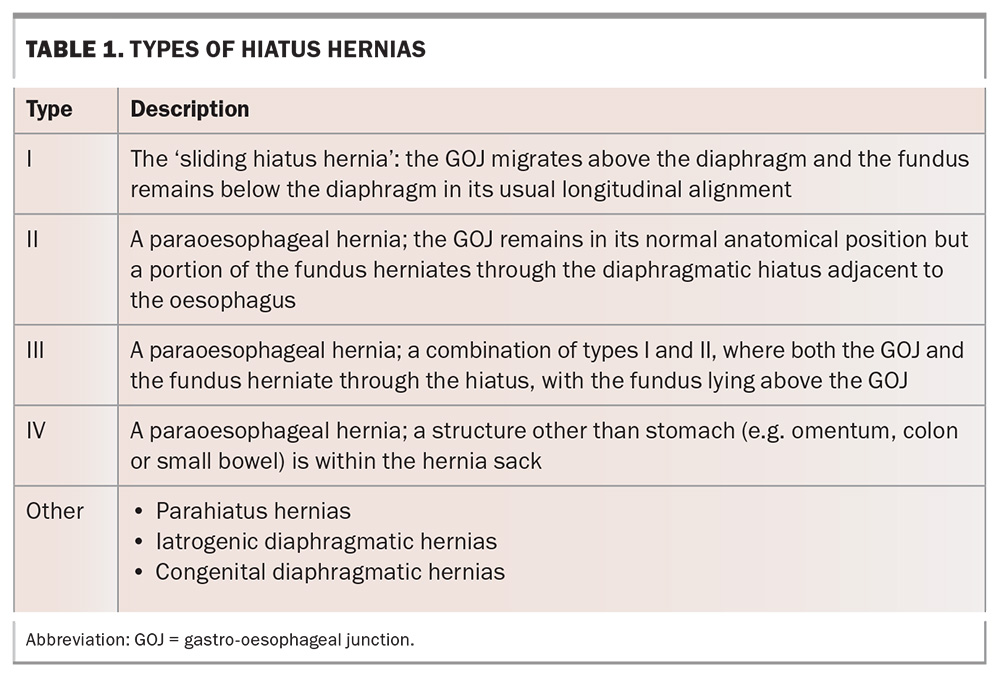

Any process that causes loss of elasticity in the phreno-oesophageal membrane or excessive contraction of the oesophagus will, over time, allow the lower oesophageal sphincter and variable parts of the fundus of the stomach to protrude proximally through the oesophageal hiatus into the thoracic cavity, leading to the development of a sliding hiatus hernia.5 Risk factors for the development of sliding hiatus hernias are listed in Table 2.6 As the hiatus widens, the GOJ slides into the chest and is contained in the posterior mediastinum. Further widening of this hiatus can lead to type III hiatus hernias.

Another potential cause of a sliding hiatus hernia is GORD. The reflux of gastric contents leads to mucosal acidification, which can trigger tonic contraction of the oesophageal longitudinal muscles. Some research suggests that prolonged or frequent acid-induced muscular contraction in patients with GORD can lead to the development of a hiatus hernia.7,8

Symptoms and effects

Symptoms of sliding hiatus hernias are largely from the subsequent GORD that can develop, and include heartburn, dysphagia and regurgitation. Some patients can present with atypical symptoms of GORD, such as a chronic cough.

Untreated GORD can lead to the development of Barrett’s oesophagus, a condition in which metaplastic columnar epithelium replaces the stratified squamous epithelium of the oesophagus and predisposes patients to oesophageal adenocarcinoma. The presence of Barrett’s oesophagus requires monitoring with gastroscopies because of the potential for its progression to oesophageal adenocarcinoma.

Rarely, patients can present with iron deficiency anaemia caused by bleeding from Cameron’s erosions (linear ulcers that occur on the part of the stomach compressed by the diaphragmatic indent).

Investigations

Hiatus hernias are often diagnosed incidentally on thoracic or abdominal imaging. Consistent assessment can be challenging given the mobile nature of the LOS – its relation to the diaphragm is dependent on swallowing and oesophageal dilatation, which can occur during instrumentation with a gastroscope. If a hiatus hernia is found incidentally on any modality, there is no need for further investigation unless there are suspicions about the type of hernia (sliding or paraoesophageal) or that it is progressing.

Imaging

Chest x-ray, CT or MRI may indicate the presence of a hiatus hernia, which will appear as a retrocardiac soft tissue opacity and can have an air-fluid level within the chest. However, the imaging modality of choice is a barium swallow. More than 2 cm of separation between the squamocolumnar junction and the diaphragmatic hiatus hernia must be seen for a diagnosis to be made; anything less than this is presumed to be physiological herniation.9 Estimation of the size of the hernia in a barium swallow examination can be difficult given its changing size, depending on when the image is taken during oesophageal peristalsis.

Oesophageal manometry is a sensitive tool for estimating the size of a hiatus hernia by comparing intragastric and intraoesophageal pressure to find the oesophageal-gastric junction, and avoids the margin of error created by swallow, distension or mucosal abnormalities encountered during barium swallow tests and endoscopy.10

pH testing can also be performed at the time of manometry; this is not necessary for the diagnosis of a hiatus hernia, but may identify increased oesophageal acid exposure in patients with sliding hiatus hernias who might benefit from anti-reflux surgery.

Endoscopy

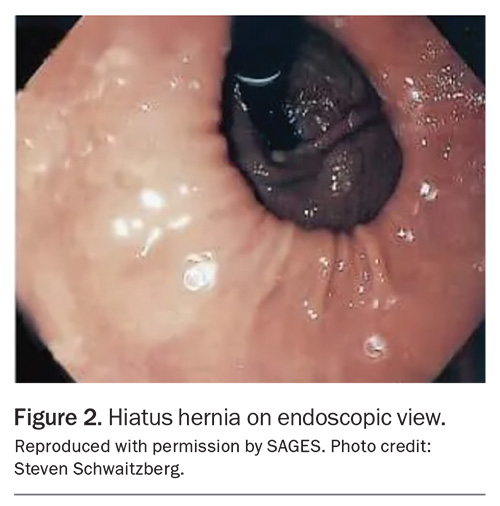

A sliding hiatus hernia can also be easily diagnosed on endoscopy when the Z line (demarcation of the squamocolumnar junction) is more than 2 cm proximal to the diaphragmatic indentation (Figure 2).11 This can also be assessed in a retroflexed position of the endoscope, looking at the GOJ from below. There is a margin for error when using this assessment in patients who have Barrett’s oesophagus because the squamocolumnar junction can become difficult to establish.

Approach to management

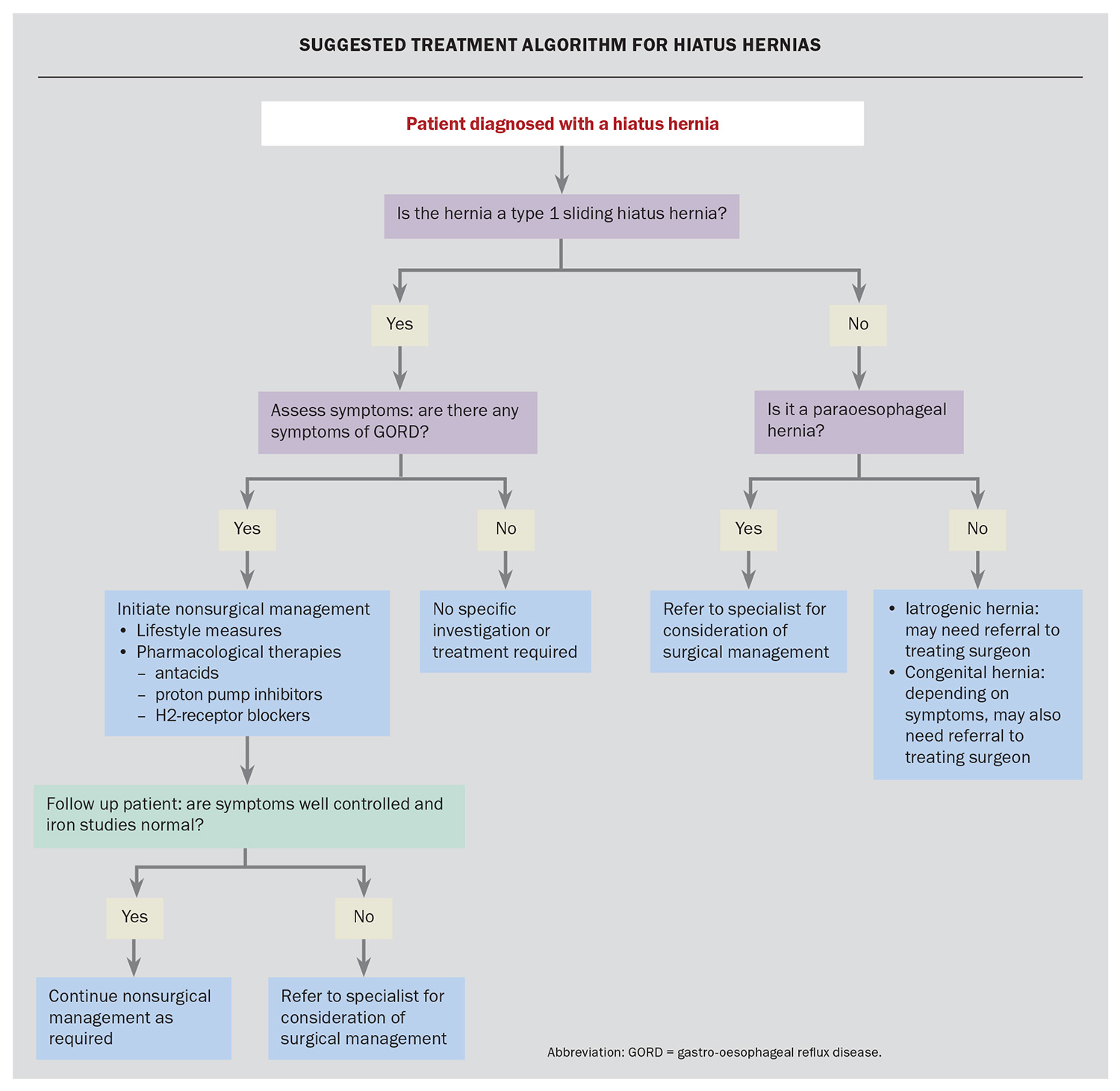

The presence of a sliding hiatus hernia in isolation does not require treatment. Usual treatment paradigms should be followed in patients who present with symptoms consistent with GORD. This consists of a stepwise approach, as seen in the Flowchart.

Lifestyle modifications

The first step in treatment is lifestyle modification, including weight loss, elevation of the head of the bed and not eating for several hours before lying down to sleep.

Pharmacological therapies

Pharmacological therapies should be initiated in the same sequence as for managing GORD. For patients with mild or intermittent disease, the first-line treatment is antacid therapy. If symptoms are not well managed with antacids alone, treatment can be escalated to intermittent proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, ideally taken 30 minutes to one hour before the first meal of the day.

For patients who have frequent or severe symptoms, we recommend a daily PPI for a period of four to eight weeks, with individualised gradual down-titration after this period to either cessation of therapy altogether or to the lowest possible dose. There are no major differences between the types of PPI in terms of efficacy. If a patient cannot tolerate a PPI, we recommend an H2-receptor antagonist.

Long-term use of a PPI should be avoided because of reported possible adverse effects, including interstitial nephritis, hypomagnesaemia and other macronutrient malabsorption, an increased risk of infections (e.g. pneumonia) or other gastrointestinal infections (e.g. Clostridioides difficile).12 PPI use has also been associated with increased cardiac risk, as well as death.13 The absolute risk of these adverse effects is low and relies on observational studies, which do not have consistency in demonstrating causality; however, they still need to be considered.

Surgical management

Surgical referral and management can be pursued if GORD symptoms are severe and persist despite maximal pharmacological therapy or if a patient has poor adherence to treatment.14 Surgical management for GORD consists mainly of the anti-reflux procedures. One option is a Nissen fundoplication, which involves wrapping the fundus of the stomach around the entire distal end of the oesophagus, anchoring it in place and reinforcing the LOS (Figure 3). Postoperative nausea and vomiting should be aggressively treated after these procedures as the persistence of these symptoms can lead to anatomical failure and the need for a revised procedure. Complications following this procedure include bloating and dysphagia.

Fundoplication leads to resolution of symptoms in about 90% of patients with GORD at 10 years.14 It can also be performed in patients with GORD in the absence of a hiatus hernia. Although this type of surgery can be used to reverse a hiatus hernia, in the absence of GORD symptoms, a hiatus hernia does not warrant surgical repair.

When to refer to a specialist

Patients with a type I sliding hiatus hernia who are asymptomatic or with symptoms of GORD that are responsive to the aforementioned treatment algorithm do not require specialist referral. Referral would be appropriate in patients with intractable and severe reflux that is not responsive to therapy, or in patients who develop iron deficiency. All patients with paraoesophageal hernias require surgical referral because of the potential for serious sequelae.

Conclusion

The majority of hiatus hernias are found incidentally, are asymptomatic and do not require any treatment. Most patients do not need specialist referral. The most common manifestation of a hiatus hernia is GORD symptoms, which should be managed with standard lifestyle and pharmacological measures. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Lim has received honoraria from Takeda Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Ltd for chairing and presenting at two events. Dr Morrison: None.

References

1. Gordon C, Kang JY, Neild PJ, Maxwell JD. The role of the hiatus hernia in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 20: 719-732.

2. Kim J, Hiura GT, Oelsner EC, et al. Hiatal hernia prevalence and natural history on non-contrast CT in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2021; 8: e000565.

3. Torborg L. Mayo Clinic Q and A: Surgery for hiatal hernias. Rochester, Minnesota, USA: Mayo Clinic News Network; 2019. Available online at: https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/mayo-clinic-q-and-a-surgery-for-hiatal-hernias/ (accessed April 2024).

4. Mittal RK. Hiatal hernia: myth or reality? Am J Med 1997; 103: 33S-39S.

5. Hill LD, Kozarek RA, Kraemer SJ, et al. The gastroesophageal flap valve: in vitro and in vivo observations. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 44: 541-547.

6. Paterson WG, Kolyn DM. Esophageal shortening induced by short-term intraluminal acid perfusion in opossum: a cause for hiatus hernia? Gastroenterology 1994; 107: 1736-1740.

7. Dunne DP, Paterson WG. Acid-induced esophageal shortening in humans: a cause of hiatus hernia? Can J Gastroenterol 2000; 14: 847-850.

8. Menon S, Trudgill N. Risk factors in the aetiology of hiatus hernia: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 23: 133-138.

9. Kahrilas PJ, Kim HC, Pandolfino JE. Approaches to the diagnosis and grading of hiatal hernia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2008; 22: 601-616.

10. Hennig A, Kurian A. Flexible endoscopy and hiatal hernias. Ann Laparosc Endoscopic Surg 2020; 6: 45.

11. Leonard J, Marshall JK, Moayyedi P. Systematic review of the risk of enteric infection in patients taking acid suppression. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 2047-2056.

12. Hyun JJ, Bak YT. Clinical significance of hiatal hernia. Gut Liver 2011; 5: 267–277.

13. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, Xian H, Yan Y, Al-Aly Z. Risk of death among users of proton pump inhibitors: a longitudinal observational cohort study of United States veterans. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e015735.

14. Dallemagne B, Weerts J, Markiewicz S, et al. Clinical results of laparoscopic fundoplication at ten years after surgery. Surg Endosc 2006; 20: 159-165.