What’s the diagnosis?

A boy with an eruption of erythematous facial papules

Case presentation

A 12-year-old boy presents with an eruption of erythematous papules around his mouth and nostrils that began several months ago. At the time of presentation, he had been treating the lesions with topical triamcinolone acetonide, which led to initial improvement but worsening each time he stopped applying it.

The patient is otherwise well. He lives with his family, who are all well and do not have a history of relevant skin disease.

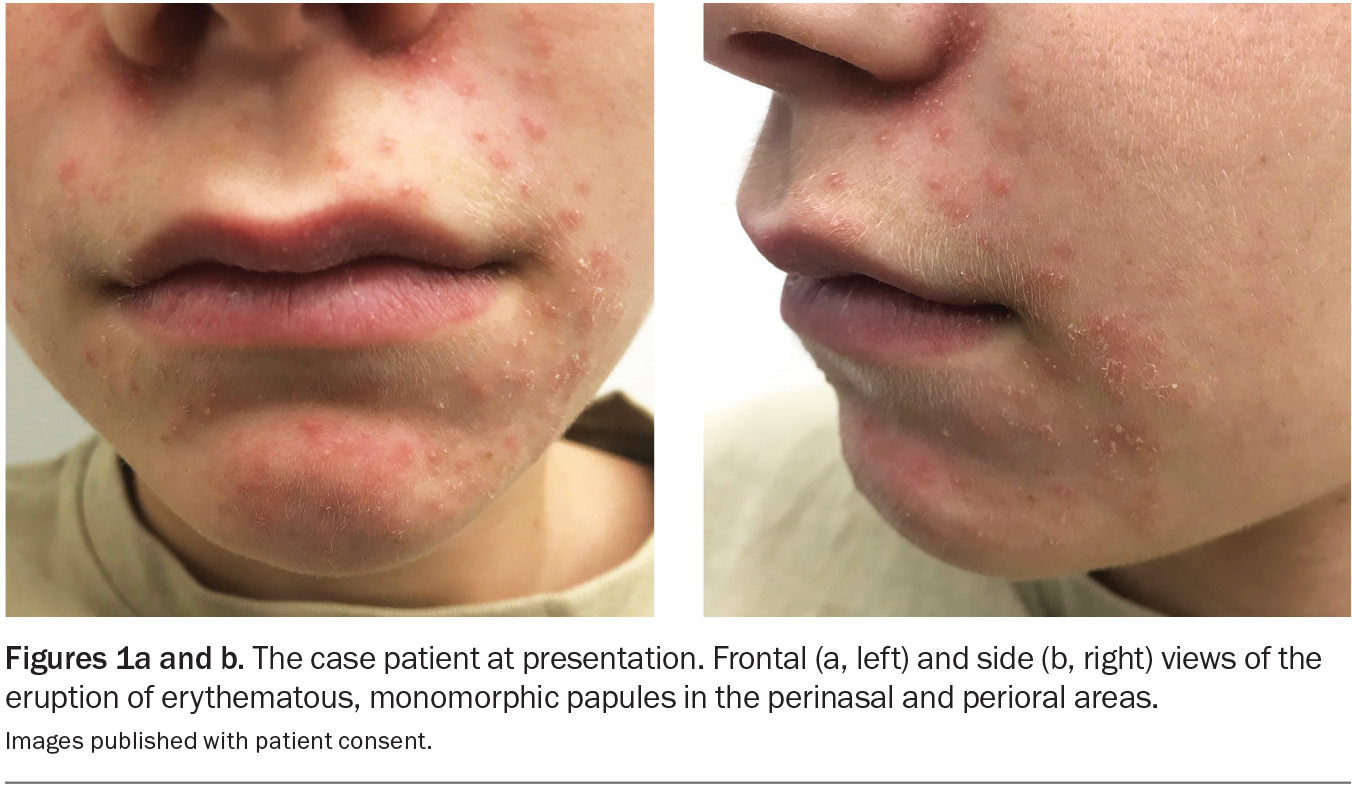

On examination, multiple erythematous, monomorphic papules are observed with a perioral and perinasal distribution (Figures 1a and b). There are no visible comedones.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Acne vulgaris

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory condition of the pilosebaceous unit. It predominately affects adolescents and young adults, with a global prevalence of 85% in individuals aged 12 to 24 years.1 The aetiology is multifactorial, involving androgen-driven sebaceous hyperactivity, follicular hyperkeratinisation, dysbiosis with Cutibacterium acnes and an inflammatory cascade that is mediated by innate immunity.2 A genetic predisposition, hormonal fluctuations and psychological stress are contributing factors.3

The lesions of acne vulgaris are divided into noninflammatory (open and closed comedones) and inflammatory (papules, pustules, nodules and cysts) groups, which are located primarily on the face, chest and back.4 The presence of comedones is a requirement for the diagnosis. Severe disease may lead to scarring and hyperpigmentation. There may be a significant psychosocial impact, including anxiety and depression.

A diagnosis of acne vulgaris is primarily clinical and based on lesion type, distribution and severity. Acne that is secondary to other causes, such as drug-induced acne and hormonal acne (e.g. associated with polycystic ovary syndrome), must be excluded in clinically relevant contexts.

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, for whom no comedones were seen on examination.

Rosacea

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin condition with centrofacial distribution. It is predominantly seen in women aged 30 to 60 years, particularly those of Celtic and northern European descent and skin phototype I or II, but all individuals may be affected, regardless of age, ethnicity or sex.5 The aetiology of rosacea is multifactorial, involving an interplay of genetic predisposition, immune system dysregulation, vascular hyper-reactivity and environmental triggers.6 The exacerbating factors include exposure to ultraviolet radiation, heat, alcohol, spicy foods, hot beverages and psychological stress, as well as certain medications, such as prolonged use of topical corticosteroids.6

The clinical presentation of rosacea varies but generally includes transient or persistent centrofacial erythema, telangiectasia and inflammatory papules and pustules that are localised to the cheeks, nose, forehead and chin.7,8 In advanced disease, patients may develop phymatous changes and/or ocular involvement.

The diagnosis of rosacea is primarily clinical, based on the characteristic distribution and morphology of lesions and a history of centrofacial flushing.9 Dermoscopy may reveal dilated blood vessels on a background of erythema. Early recognition and management are crucial to prevent progression and minimise the impact on quality of life.

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, who did not have a history of centrofacial erythema, and no telangiectasia were seen.

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis is caused by a delayed (type IV) hypersensitivity reaction. Initial sensitisation occurs when there is direct skin contact with an offending

substance that leads to activation of T lymphocytes, which trigger an eczematous inflammation of the skin when subsequent exposures occur.10 It is estimated that at least 20% of the general population have a contact allergy to at least one environmental allergen, with the prevalence being significantly higher in women than men.11 Common allergens include nickel (e.g. in costume jewellery), fragrances in perfumes and cosmetics, and accelerants used in the manufacture of rubber products (e.g. in gloves, shoes).11

Allergic contact dermatitis has a variety of different morphologies, including erythema, oedema, pruritic vesicles, blisters and an eczematous eruption. Chronic or repeated exposure may lead to lichenification, scaling and fissuring.12 It most frequently affects areas that are in direct contact with environmental allergens (hands, feet, lips). However, although the eruption is generally confined to areas of exposure, it may not remain limited to the initial site of contact.

The diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis is based on clinical examination and supported by a history of exposure to a putative allergen. Patch testing may be used to identify the cause – this involves applying allergens to the skin and observing for reactions after 48 to 96 hours.12

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. Although topical triamcinolone may cause allergic contact dermatitis, the morphology of his eruption (monomorphic papules) was not consistent with this diagnosis.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is a common inflammatory skin condition affecting individuals of all ages and ethnicities.13 Its aetiology is multifactorial, involving genetic predisposition, immune dysfunction and hormonal factors. Colonisation of the skin by Malassezia species, a commensal yeast, is believed to be pivotal in the pathogenesis, triggering an inflammatory response that leads to flares.14 There are many postulated triggers, including cold weather, stress, nutritional deficiencies (B-group vitamins, essential fatty acids, vitamin D, zinc), hormonal

fluctuations, immunosuppression, certain medications (androgenic medications, antipsychotics, immunosuppressants, lithium) and some neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy.15,16

Seborrhoeic dermatitis presents as poorly defined, erythematous, scaly patches with little or no pruritus.17 In adults, the condition mainly affects sebaceous gland-rich areas, such as the face (especially the eyebrows, glabella, nasolabial folds and area around the ears), scalp, axillae, chest and skinfolds. In infants, it usually affects the scalp (cradle cap), axillae and groin. Scalp involvement is characterised by greasy, thin, yellowish scales that may adhere to hair shafts. There is no associated scarring or permanent hair loss.

Diagnosis is based primarily on clinical characteristics. Trichoscopy reveals thinner, yellowish scales and diffuse erythema.18 If the diagnosis is unclear, a scalp biopsy may be performed and will typically reveal parakeratosis, spongiosis and mild perivascular infiltrates; however, this is seldom required.19

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. Although his skin eruption was distributed in the nasolabial folds, its morphology was not consistent with seborrhoeic dermatitis.

Periorificial dermatitis

This is the correct diagnosis. Periorificial dermatitis is a common inflammatory facial dermatosis characterised by clusters of erythematous or skin-coloured papules, pustules and scaling. The perioral region is the most likely site of distribution, often with sparing of the vermilion border; however, the periocular and paranasal skin can also be affected.

Although the exact cause of periorificial dermatitis remains unknown, several contributing factors have been identified. One of the most recognised triggers is prolonged or frequent use of topical corticosteroids, which can disrupt the skin barrier function, induce vasodilation and alter local microbial flora – all of which promote inflammation.20 Certain facial creams, moisturisers and fluoridated toothpaste have been implicated, either through irritation or occlusion.21,22 Dysbiosis of the skin microbiome, including overgrowth of Candida species, may contribute to inflammation and skin barrier dysfunction.23,24 Environmental and lifestyle factors, such as exposure to ultraviolet radiation, psychological stress and improper skincare practices (e.g. overuse of harsh facial cleansers) are other contributors.23

Periorificial dermatitis is most common in women aged 20 to 25 years but can affect all people, regardless of age or sex.25 Its prevalence has been rising in recent years due to the increasing popularity of cosmetic products.26 Paediatric cases are often associated with inhaled corticosteroids used for managing asthma.27

The diagnosis of periorificial dermatitis relies primarily on clinical features. A thorough patient history is essential and should include details about the use of topical or inhaled corticosteroids, skincare products and toothpaste. For cases that are atypical or unresponsive to treatment, a skin biopsy may be considered. Histopathology findings are nonspecific and often include perifollicular and perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate with sparse plasma cells and occasional giant cells.28,29

Management

The effective management of periorificial dermatitis will require a multifaceted approach, beginning with the elimination of known triggers. Topical corticosteroids must be discontinued – this is essential for long-term improvement. Abrupt withdrawal often leads to a temporary worsening of symptoms, and gradual tapering may be necessary for severe dependence.28

For mild cases of periorificial dermatitis, topical treatments such as metronidazole 0.75% gel or cream, clindamycin 1% lotion or solution, or pimecrolimus 1% cream may be effective. These agents reduce inflammation, promote skin barrier repair and address potential microbial dysbiosis.28

For moderate or severe cases, systemic antibiotics, such as doxycycline 50 to 100 mg once or twice a day, minocycline 100 mg once or twice a day, or erythromycin 250 to 500 mg daily, may be used for their anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties. Treatment typically lasts for 12 weeks.30,31

Modifications to skincare routines may be necessary. Long-term successful management requires patient education about using gentle noncomedogenic cleansers and maintaining the skin barrier with moisturisers. Avoiding known triggers, heavy cosmetics and fragranced skincare products is crucial.25

With timely and appropriate treatment, periorificial dermatitis typically resolves within weeks to months. However, recurrence is common, particularly if triggers such as topical or inhaled corticosteroids or irritants are reintroduced. The overall prognosis is excellent.31

Outcome

The case patient was given a clinical diagnosis of periorificial dermatitis. He was advised to stop applying topical triamcinolone acetonide, which is too potent for use on the face. Although he had had an initial therapeutic response, he then experienced a withdrawal flare, which is a hallmark of periorificial dermatitis.

The diagnosis was explained and the boy was commenced on oral doxycycline 50 mg daily for 12 weeks. He was educated about the importance of avoiding strong corticosteroids on his face and given information about skincare measures to protect the barrier function. On review 12 weeks later, he had no signs of periorificial dermatitis. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Tan JKL, Bhate K. A global perspective on the epidemiology of acne. Br J Dermatol 2015; 172 Suppl 1: 3-12.

2. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74: 945-973.e33.

3. Heng AHS, Chew FT. Systematic review of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 5754.

4. Knutsen-Larson S, Dawson AL, Dunnick CA, Dellavalle RP. Acne vulgaris: pathogenesis, treatment, and needs assessment. Dermatol Clin 2012; 30: 99-106.

5. Elewski B, Draelos Z, Dréno B, Jansen T, Layton A, Picardo M. Rosacea – global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011; 25: 188-200.

6. van Zuuren EJ. Rosacea. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1754-1764.

7. Tan J, Almeida L, Bewley A, et al. Updating the diagnosis, classification and assessment of rosacea: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 431-438.

8. Schaller M, Almeida L, Bewley A, et al. Recommendations for rosacea diagnosis, classification and manage-ment: update from the global ROSacea COnsensus 2019 panel. Br J Dermatol 2020; 182: 1269-1276.

9. van Zuuren EJ, Arents BW, van der Linden MM, Vermeulen S, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J. Rosacea: new concepts in classification and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2021; 22: 457-465.

10. Gober MD, Gaspari AA. Allergic contact dermatitis. Curr Dir Autoimmun 2008; 10: 1-26.

11. Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP, Johansen JD. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis 2019; 80: 77-85.

12. Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, Pootongkam S, Nedorost S, Brod B. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74: 1029-1040.

13. Polaskey MT, Chang CH, Daftary K, Fakhraie S, Miller CH, Chovatiya R. The global prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2024; 160: 846-855.

14. Rosso JQ, Kim GK. Seborrheic dermatitis and malassezia species: how are they related? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2009; 2: 41-44.

15. Kim KM, Kim HS, Yu J, Kim JT, Cho SH. Analysis of dermatologic diseases in neurosurgical in-patients: a retrospective study of 463 cases. Ann Dermatol 2016; 28: 314-320.

16. Wilkowski CM, Alhajj M, Kilbane CW, Kumar Y, Bordeaux JS, Carroll BT. The association of seborrheic dermatitis and Parkinson’s disease: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2025; 92: 157-159.

17. Gupta A, Bluhm R. Seborrheic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2004; 18: 13-26.

18. Golińska J, Sar-Pomian M, Rudnicka L. Diagnostic accuracy of trichoscopy in inflammatory scalp diseases: a systematic review. Dermatology 2022; 238: 412-421.

19. Park J-H, Park YJ, Kim SK, et al. Histopathological differential diagnosis of psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp. Ann Dermatol 2016; 28: 427-432.

20. Tempark T, Shwayder TA. Perioral dermatitis: a review of the condition with special attention to treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol 2014; 15: 101-113.

21. Peters P, Drummond C. Perioral dermatitis from high fluoride dentifrice: a case report and review of literature. Aust Dent J 2013; 58: 371-372.

22. Abeck D, Geisenfelder B, Brandt O. Physical sunscreens with high sun protection factor may cause perioral dermatitis in children. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2009; 7: 701-703.

23. Balić A, Vlašić D, Mokos M, Marinović B. The role of the skin barrier in periorificial dermatitis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2019; 27: 169-179.

24. Takiwaki H, Tsuda H, Arase S, Takeichi H. Differences between intrafollicular microorganism profiles in perioral and seborrhoeic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2003; 28: 531-534.

25. Lipozencic J, Ljubojevic S. Perioral dermatitis. Clin Dermatol 2011; 29: 157-161.

26. Lipozencic J, Hadzavdic SL. Perioral dermatitis. Clin Dermatol 2014; 32: 125-130.

27. Kellen R, Silverberg NB. Pediatric periorificial dermatitis. Cutis 2017; 100: 385-388.

28. Laude TA, Salvemini JN. Perioral dermatitis in children. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1999; 18: 206-209.

29. Marks R, Black MM. Perioral dermatitis. A histopathologic study of 26 cases. Br J Dermatol 1971; 84: 242-247.

30. Coskey RJ. Perioral dermatitis. Cutis 1984; 34: 55-58.

31. Weber K, Thurmayr R. Critical appraisal of reports on the treatment of perioral dermatitis. Dermatology 2005; 210: 300-307.

Facial injuries and disorders