Cosmetic botulinum toxin and filler injectables: indications, risks and best practices

Cosmetic injectables, such as botulinum toxin injections and skin fillers, are widely popular in Australia, with the market projected to grow substantially in the coming years. Regulatory bodies in Australia have issued guidelines to ensure patient safety and practitioner competence to mitigate risks associated with these procedures.

- Cosmetic botulinum and filler injectables are increasingly popular among a diverse demographic.

- There is increasing regulatory oversight of cosmetic injectables and a set of guidelines available for practitioners performing cosmetic procedures to ensure ethical and safe practice.

- Botulinum toxin injections have both cosmetic and medical indications but are mostly used to ameliorate facial expression lines. Hyaluronic acid fillers are popular for enhancing facial volume and smoothing wrinkles.

- Both botulinum toxin and filler injections have potential complications. Some of these adverse effects are serious and catastrophic, such as blindness from vascular occlusion, and should be discussed with the patient.

- The emergence of ‘DIY’ injectables poses a concerning trend, warranting stricter regulations and targeted education.

In aesthetic medicine, minimally invasive procedures such as botulinum toxin injections and filler injections are popular choices among consumers and patients seeking cosmetic enhancement. Although women remain the main consumers of cosmetic procedures, the range of individuals seeking these services has become progressively more diverse in age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic background.1 The Australian facial injectable market was valued at US$2.6 billion (more than $3.9 billion) in 2023 and is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 24.1% from 2024 to 2030.1 Botulinum toxin and filler injections consistently top this list.

Cosmetic procedures feature prominently on social media platforms, such as Instagram, TikTok and YouTube, creating an allure around these treatments. Procedures are being delivered by a range of practitioners with varying degrees of expertise and scope of practice. In response to these trends, and to safeguard the interests of consumers and patients, the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency has proposed developing a set of guidelines for practitioners performing cosmetic procedures, including the regulation of cosmetic injectables, which are classified as Schedule 4 prescription products.2 The TGA has also developed an interest in the marketing and advertising of these Schedule 4 agents. This article provides an overview of botulinum toxin and skin fillers and discusses their indications, contraindications, intended outcomes and potential complications.

Botulinum toxin type A

Botulinum toxin type A (BoNTA) is a naturally occurring toxin derived from Clostridium botulinum, which is harmful if ingested or introduced in large quantities. However, when injected in its purified form and in small doses into facial muscles, it is considered safe, as it does not significantly enter the systemic circulation.3 For cosmetic procedures, BoNTA is available in Australia as onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox), incobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin), letibotulinumtoxinA (Letybo) or abobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport).

When injected into muscles or areas of sweat glands, BoNTA acts by blocking the nerve signals that trigger muscle contractions or sweat gland function. In the face and neck, this results in reduced muscle activity, minimising the intensity of facial movements that contribute to expression lines and wrinkles.3 The effects of BoNTA usually appear from day 3 onwards and are usually established by day 7 to 10, lasting for about three to four months before movement returns. Both dynamic lines (lines appearing with facial movement) and static lines (lines present at rest) tend to improve with the onset of BoNTA action. Prominent static lines will not immediately clear but will progressively soften with ongoing use of BoNTA. For treating sweat gland function, onset may be more gradual but tends to last longer, often six to eight months.

Indications of botulinum toxin type A

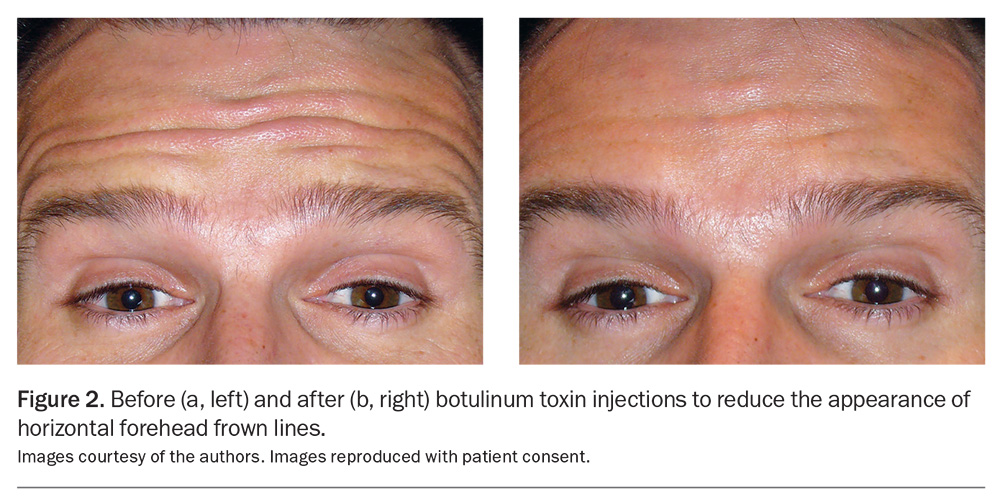

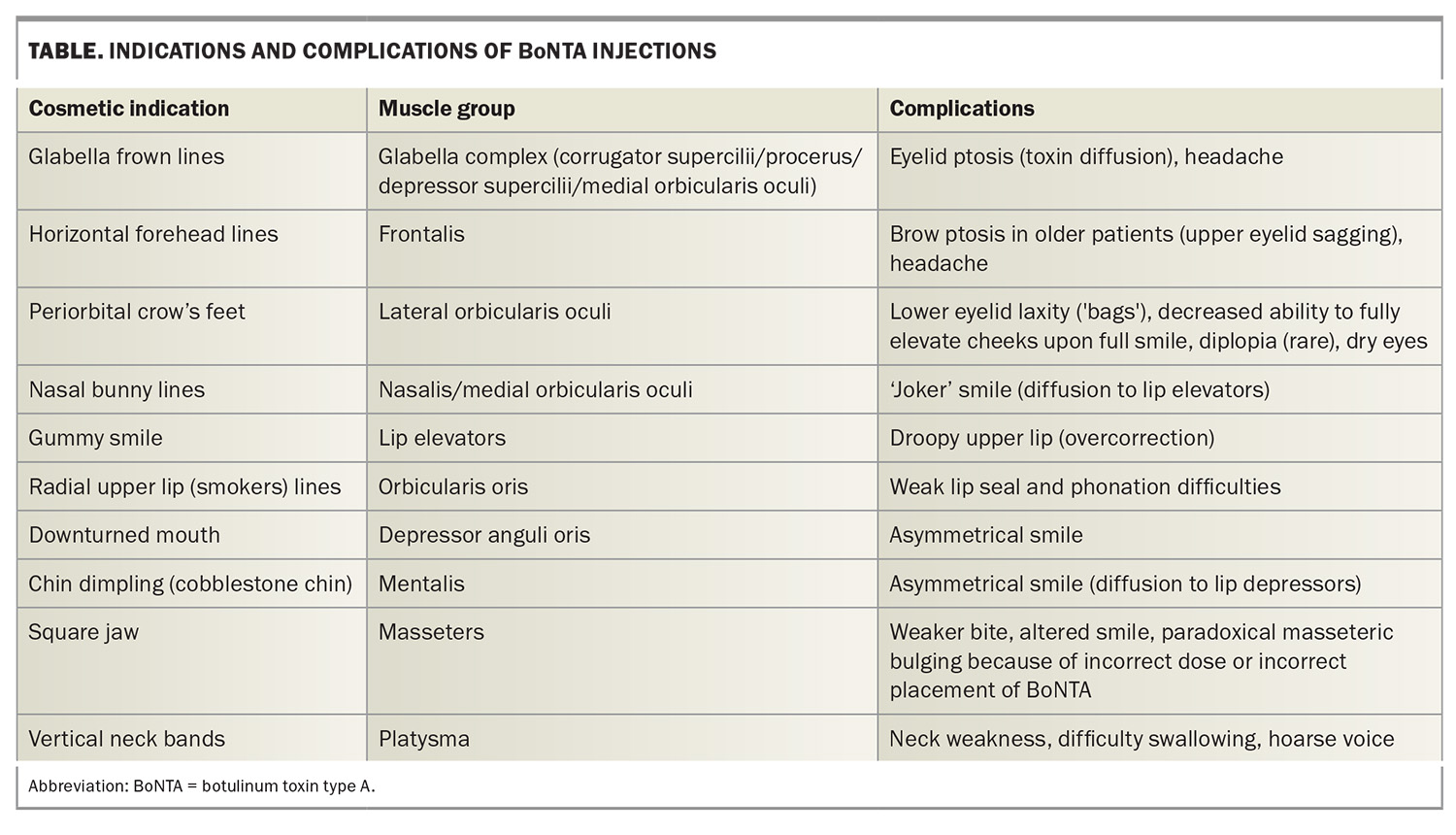

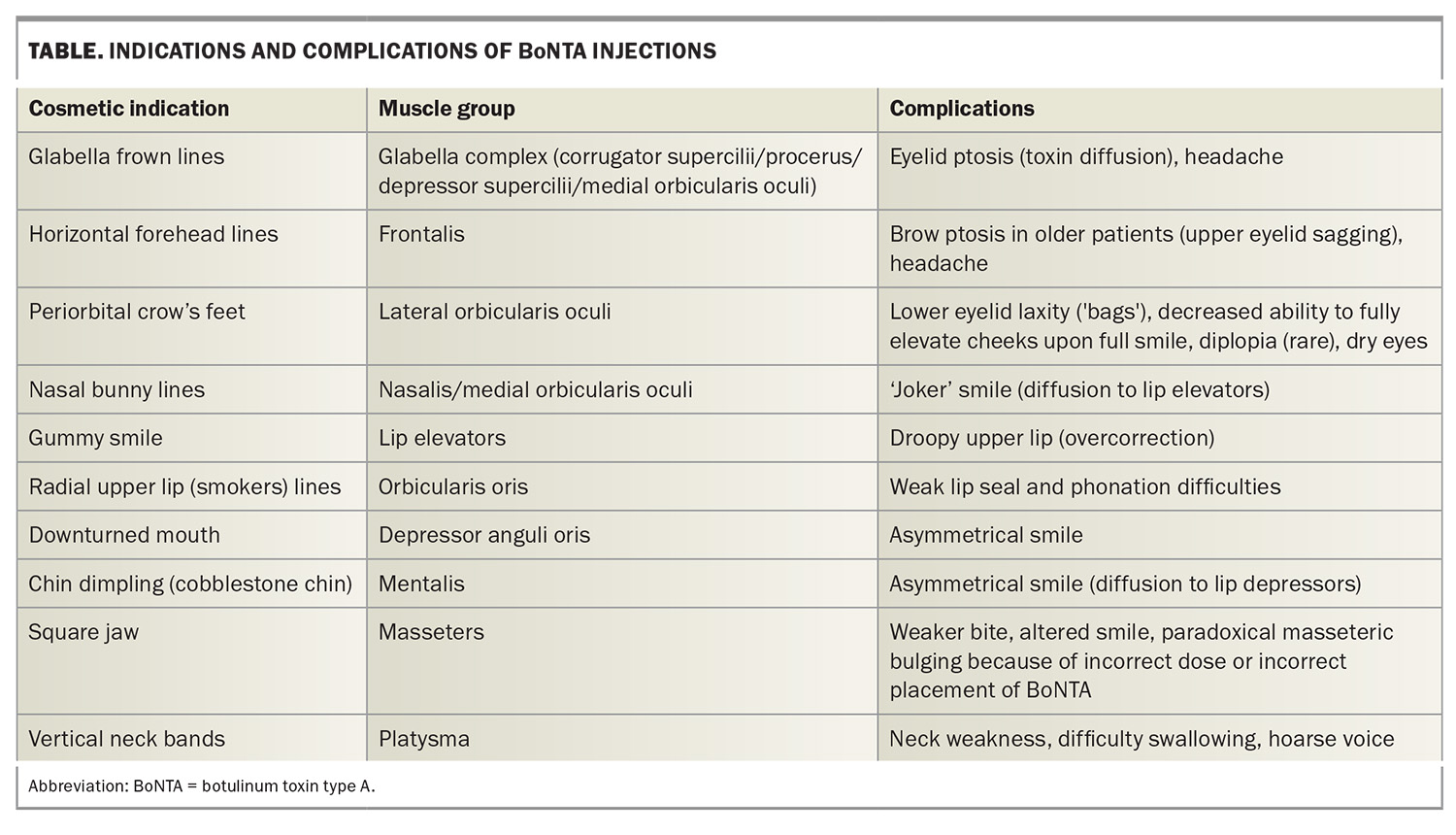

One of the earliest approved and classic BoNTA indications was injection into the corrugator muscles situated above the medial eyebrows to mitigate the pronounced vertical frown lines produced when the inner eyebrows converge. BoNTA has emerged as a safe and established treatment option for upper and lower facial lines and wrinkles, such as periorbital ‘crow’s feet’ (Figure 1a and 1b) and horizontal frown lines on the forehead (Figure 2a and 2b) and for the lower face.3 Over the years, the cosmetic indications for BoNTA have broadened to include various facial and neck muscles. BoNTA is TGA approved for the treatment of upper facial rhytides (glabellar lines, crow’s feet and forehead lines) in adults; however, other ‘off-label’ but well-recognised treatment areas are also routinely targeted. Popular cosmetic indications for BoNTA are presented in the Table.

Aesthetics aside, BoNTA has many medical applications. Patients with masseter hypertrophy are frequently teeth grinders and may experience facial pain and headaches. BoNTA injections can significantly improve their dentition and pain, owing to a reduction in involuntary teeth grinding (bruxism). Cosmetically, treatment of the masseter muscles can be used to contour a square jaw, resulting in a ‘slimmed’ facial appearance. Patients also report relief from tension headaches after BoNTA injections into the forehead (frontalis muscle) and glabella complex (corrugator muscles). Axillary or palmoplantar hyperhidrosis can be debilitating and responds well to BoNTA injections, which should be considered when conservative measures are unsuccessful. Other noncosmetic indications for BoNTA include the treatment of blepharospasm, muscle spasticity, chronic migraine, facial flushing and erythema, scars and excessive salivation.4

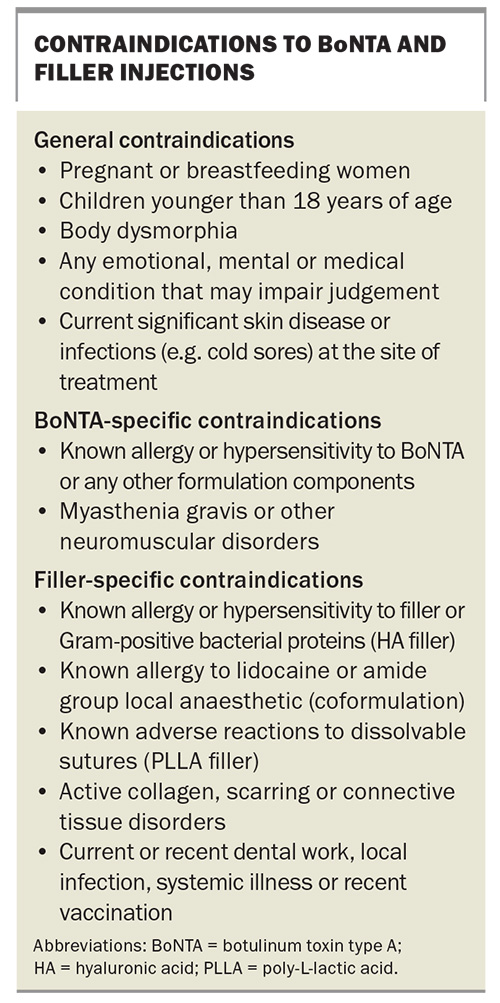

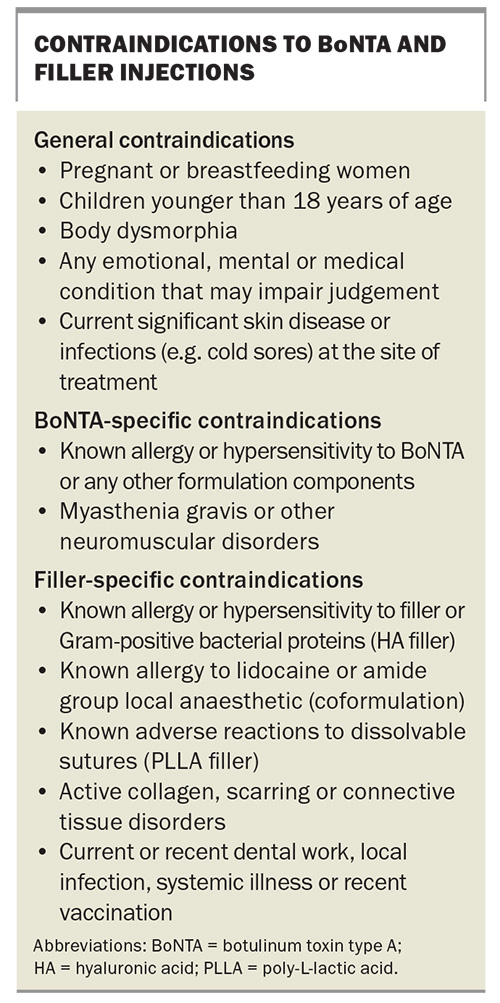

The contraindications of botulinum toxin are listed in the Box.

Adverse outcomes of botulinum toxin type A

Cosmetic BoNTA injections are generally safe with minimal intra- and postprocedural risks.5 The adverse effect profile is generally minor and self-limiting. However, some adverse effects are less common and less recognised (e.g. dry eyes and double vision).6

Common adverse effects include mild injection discomfort, temporary localised swelling and bruising at the injection site. Bruising can be socially inconvenient for the patient and can be minimised by ceasing unnecessary blood thinners, such as vitamin E and fish oil supplements, and avoiding visible veins and immediate postinjection pressure. Patients taking self-initiated low-dose aspirin and blood-thinning supplements should be advised to cease the medications about one week prior to minimise bleeding and bruising. However, prescribed blood thinners, including aspirin, in the setting of established cardiovascular disease should be continued without interruption.

Although not strictly an adverse outcome, patient aesthetic expectations may not be met because of dose- or endpoint-related issues from too much or too little facial movement postinjection. Adequate preprocedure counselling should help mitigate this. Patients with body dysmorphic disorder will invariably be dissatisfied with treatment outcomes and it is preferable to identify and exclude these individuals from treatment from the outset.

Less common adverse outcomes

Unintended injection or diffusion of BoNTA into adjacent muscles can result in facial asymmetry and ptosis of the brow or eyelids.5

Brow ptosis

Brow ptosis results from overzealous or too inferiorly placed injections into horizontal forehead ‘worry lines’. This causes excessive weakening of the frontalis muscle and subsequent descent of the eyebrow position, resulting in worsening of eyelid hooding and a tired-looking appearance. At-risk patients are typically older individuals with pre-existing hooded eyelids and compensatory frontalis activity to elevate the brow and ‘open’ the eyes (characterised by prominently etched forehead creases at rest). In these patients, BoNTA-induced relaxation of the frontalis muscle of the forehead will drop the brow and eyelids to the point at which vision may be obscured.

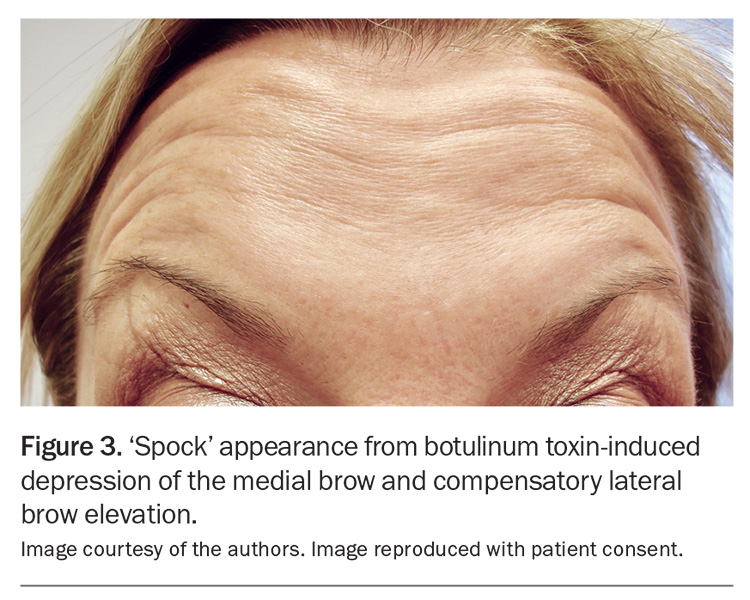

Medial brow ptosis may result from incorrectly placed injections when attempting to treat the glabella frown lines. This undesired outcome may occur if injections into the glabella corrugator muscles are placed too superficially at the medial point, or too superiorly, which will weaken and drop the medial frontalis muscle and induce compensatory lifting of the lateral frontalis muscle. This depression of the medial brow and compensatory lateral brow elevation may result in a sinister or quizzical appearance, popularly known as the ‘mephisto sign’ or ‘spocking’ of the eyebrows (Figure 3).

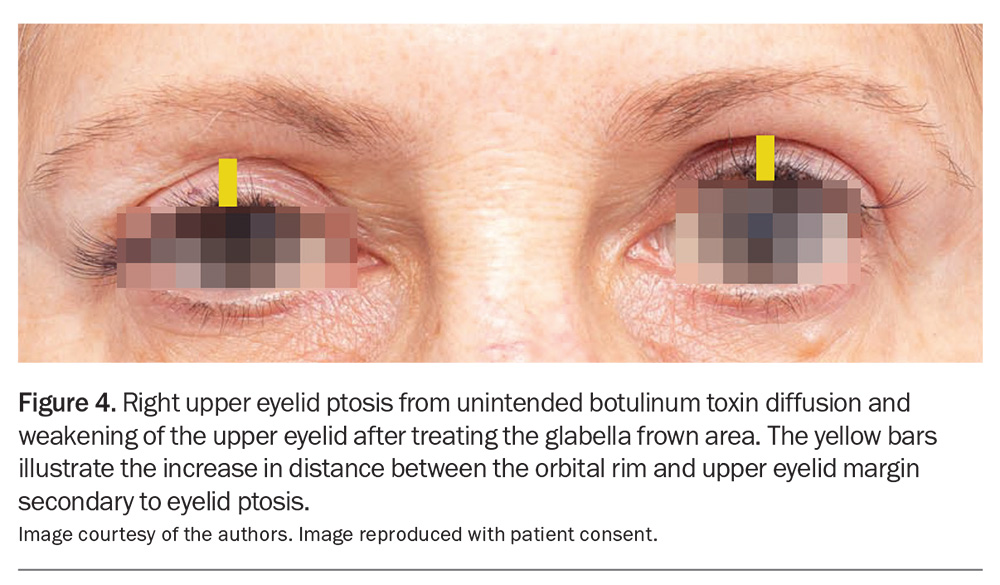

Eyelid ptosis

Eyelid ptosis results from unintended weakening of the levator palpabrae superioris muscle that is responsible for involuntary autonomic eyelid widening. This typically results from cosmetic injection into the corrugator muscle at the midpupillary line to control glabella frown lines. Weakening of this autonomically innervated muscle – through either diffusion or direct injection – results in ptosis of the eyelid. Eyelid ptosis can be improved with 0.5% apraclonidine (alpha-2-adrenergic agonists) eyedrops applied every few hours or as required. Compared to brow ptosis, eyelid ptosis is usually unilateral with preservation of the eyebrow position (Figure 4).

Paradoxical headache

Paradoxical headaches may occur after BoNTA injections into the forehead or glabella frown lines and tend to diminish with subsequent repeat sessions. More typically, patients may observe that tension headaches improve with BoNTA injections, which is the primary therapeutic indication for some patients.3

Other adverse outcomes

Uncommon and rare adverse effects include BoNTA-induced weakness and asymmetry of facial expression secondary to BoNTA diffusion beyond the target muscles (Table).5, 6

Unusually, patients may report xerophthalmia (dry eyes) secondary to the inhibitory effect of BoNTA on lacrimal gland secretion.5,6 Paradoxically, BoNTA has been used to treat dry eyes in patients by injecting the medial lower eyelid to weaken and interrupt the orbicularis muscle pump that facilitates lacrimal drainage via the lacrimal canniculi.7

Skin fillers

Hyaluronic acid fillers

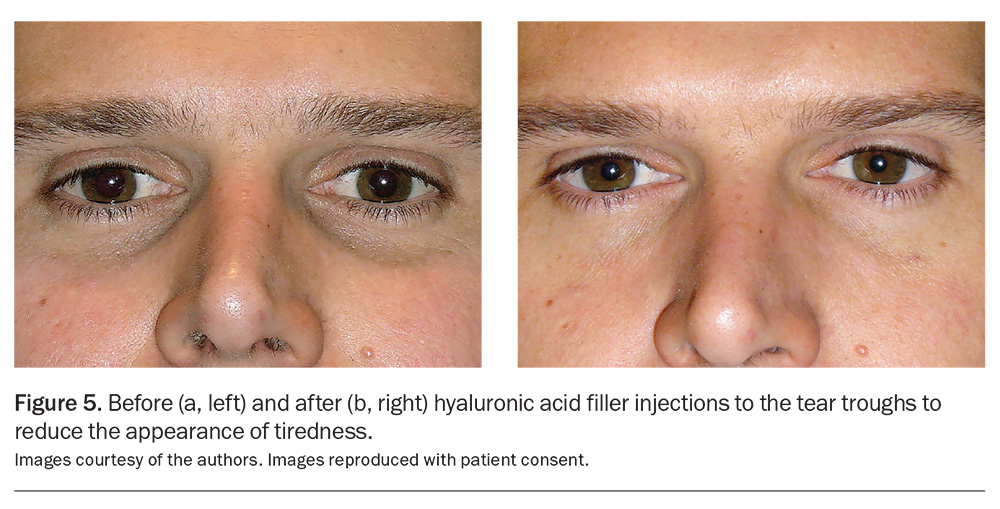

Fillers are indicated to smooth out wrinkles, creases and furrows, as well as to enhance facial volume in areas such as the lips, cheeks, temples or tear troughs (Figure 5a and 5b). Hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers are the most popular choice because of their versatility, safety and durability. HA is a naturally occurring proteoglycan present in all living tissues, including in humans. Given its consistency across species and its low rate of true allergy, there is no need for allergy testing. HA is both biocompatible with human tissue and naturally biodegradable, and can be dissolved with hyaluronidase.8 Fillers are often used in combination with BoNTA injections, as their actions are synergistic.

The longevity of a filler is predominantly influenced by its type, its consistency (degree of crosslinking and particle size) and the anatomical location of application. For instance, less viscous HA fillers usually last three to six months, whereas more viscous HA fillers can last six to 18 months. High-movement areas, such as around the mouth, may cause the filler to dissipate more quickly, resulting in a reduced duration. Additionally, the lifespan of the filler can vary among individuals.

More recently, a bioremodelling HA injectable (Profhilo) has become available in Australia.9 This hybrid high- and low-molecular-weight HA has a hydrating effect on the skin, as well as a collagen remodelling effect to reduce the appearance of wrinkles and skin laxity, as opposed to a volumising effect from conventional HA fillers.

The contraindications of HA fillers are listed in the Box.

Non-hyaluronic acid fillers

In Australia, poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA), calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA) and polycaprolactone are among the temporary non-HA fillers available, with additional options anticipated for the market in the future. PLLA is a synthetically produced material comprising lactic acid chains that naturally degrade over time. CaHA is composed of tiny, smooth calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres that also break down gradually. Both PLLA and CaHA fall under the category of biostimulating fillers, as they promote collagen formation and can sustain tissue-filling effects for about 12 to 18 months. Polycaprolactone microspheres stimulate collagen remodelling via an inflammatory process with minimal hydrating effects and has been advocated for skin laxity and wrinkles.

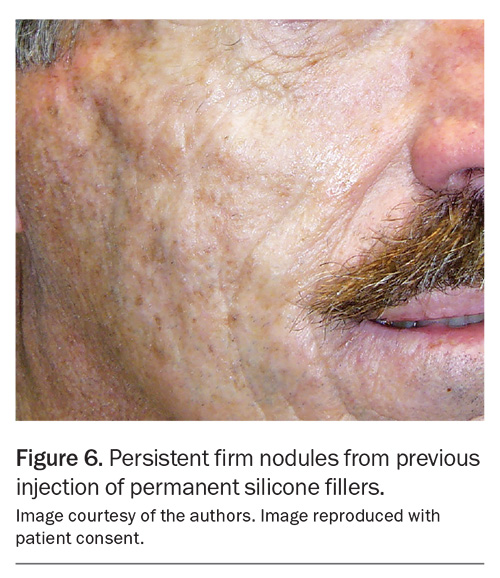

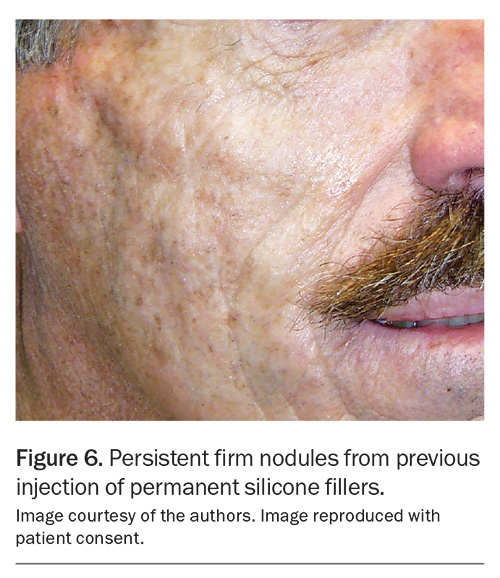

The only permanent skin filler routinely employed in Australia is the polyacrylamide hydrogel filler. However, the use of permanent fillers comes with potential long-term complications, including the development of nodules and granulomas, cysts, sinuses, inflammation and infections, which can be challenging to address (Figure 6).10 As such, permanent fillers should not be considered as a first-line filler option.

Adverse outcomes of hyaluronic acid fillers

As fillers are filling agents intended to modify tissue volume and contour, there is the added risk of product visibility because of it being placed too superficially, an asymmetrical appearance and, most concerningly, potential vascular occlusion resulting in skin necrosis, blindness and, very rarely, strokes.5

Like with BoNTA injections, mild injection discomfort and redness, localised swelling and bruising are common temporary adverse effects. Periprocedure application of ice at the injection point can alleviate pain and reduce the extent of bruising in the event of vessel puncture.

Fillers placed too superficially may result in unsightly papules and beads and may also show a bluish discolouration from filler-induced light scattering, known as the Tyndall effect.5 When injecting bilaterally, inconsistent depth and quantity of filler placement may result in contour asymmetry. Overfilling the cheeks, lips, tear troughs or temples may result in an unnatural appearance.

Acute bacterial infection, such as staphylococcal skin infection, is uncommonly encountered but certainly possible if an aseptic technique is not undertaken, or injections are given through broken skin. However, lip fillers can occasionally trigger a cold sore through the injection trauma activating quiescent herpes simplex virus infection in susceptible individuals. An aseptic technique is essential for filler injections, and antiviral prophylaxis may be selectively considered.

HA fillers characteristically attract water, which is an inherent physiological trait known as ‘gel swelling’ potential.11 Different HAs have different swelling potentials, and fillers with increased swelling potential will bind water more readily to cause swelling, which can be particularly problematic in the lower eyelids. Fillers injected in the region of the lower eyelids should be appropriately selected for minimal swelling potential, and the injected amount should be conservative to minimise lower eyelid puffiness. Careful assessment of the periorbital area is essential, and treatment alternatives such as surgery may need to be discussed with the patient.

Less common adverse outcomes: early- and late-onset nodules

Filler nodules – early or late – can be classified as inflammatory nodules or noninflammatory ‘cold’ nodules.12,13 Although there remains no clear explanation for the occurrence of these nodules, the consensus is that both inflammatory and noninflammatory nodules have an immunological basis.12,13

In the past, permanent fillers such as silicone and polyacrylamide have been responsible for the majority of late-onset nodules, typically emerging months to years after the procedure (Figure 6).10 Biopsy of these nodules show granulomas suggesting that the immune system is reacting to the filler agent or related contaminant (e.g. filler impurities, bacterial biofilm).14 HA fillers have a very low incidence of immunological nodule formation, as they are naturally occurring polysaccharides found in all living tissue including the skin.15 However, as non-HA fillers are becoming less popular or discontinued, HA-related complications, such as the development of late-onset nodules, are now becoming proportionately more prevalent.

Inflammatory nodules may be associated with low-grade bacterial biofilm activity.14,16 The biofilm is a network of a bacterial microbiome embedded in an extracellular matrix composed of proteins and polysaccharides, and adherent to the filler. Dental plaque is an example of a biofilm coating the teeth. Biofilms tends to evade the immune system and are therefore typically persistent and recalcitrant and only detectable on polymerase chain reaction assays, rather than bacterial culture tests.16 Inflammatory filler nodules are typically treated with antibiotics, drainage and dissolution of the filler with hyaluronidase as a last resort.12,13,16

The onset of noninflammatory filler nodules can often be delayed (six months or longer following fillers), and patients may present to their GP unaware of the link between the two events. Typically, the diagnosis of reactive filler nodules is then suggested based on history and soft tissue scanning (ultrasound) findings. Facial fillers can be incidentally highlighted on scans (ultrasound or MRI) performed for unrelated reasons and may cause confusion if the filler history has not been offered.

The management of noninflammatory filler nodules can vary, ranging from a monitoring strategy for nodules that are not visible to active treatment using one or more of the following: hyaluronidase, antibiotics, corticosteroids (either intralesional or systemic) and nonsteroidal immunosuppressive or anti-inflammatory treatments.12,13 Patients should be referred back to the original injector or a skilled clinician for further care.

Late-onset nodules (inflammatory or noninflammatory) can form in areas previously treated with HA fillers following dental procedures, local infections (e.g. sinusitis or abscesses) or systemic illnesses (e.g. COVID-19 or influenza). It has been postulated that the interplay between the HA degradation products, the presence of viraemia or bacteraemia and an activated immune response may trigger the development of these nodules.10,12

Other adverse outcomes: vascular occlusion

Vascular occlusion leading to blindness is a rare but catastrophic filler complication. As of 2020, there have been 233 reported cases of blindness linked to the use of HA fillers, non-HA fillers and autologous fat transfer procedures.17 Most vascular occlusion affecting the ophthalmic arterial vasculature will lead to complete and permanent blindness.17,18 From 2015 to 2018, 60 cases of filler-associated blindness were reported globally: 72% involved complete and irreversible damage and 17% involved concomitant acute ischaemic stroke. The most common type of filler was HA (70%).18

Vision-compromising vascular occlusion is a medical emergency because permanent blindness can occur in as little as 15 minutes.18 As a proportion of these patients will experience a neurological ischaemic event, patient transfer should occur via an ambulance. All filler injectors must be familiar with the facial arterial anatomy, be able to promptly recognise arterial compromise and execute a validated management algorithm including immediate review by an oculoplastic or ocular surgeon in the event of a vascular occlusion emergency.13,16-18

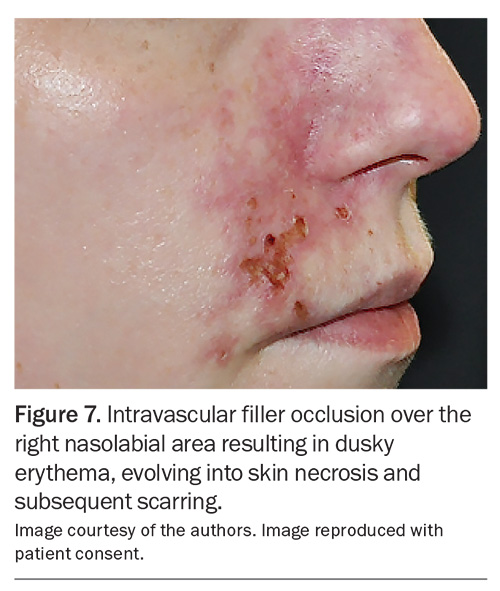

Vascular occlusion can occur in the terminal cutaneous arterioles and cause skin necrosis by disruption of the blood supply to an area of skin (Figure 7). As this can result in scarring, prompt recognition and treatment are important. Compared with threatened vision loss, skin ischaemia is more amenable to salvage strategies, and full reversal is often possible with prompt and repeated infiltration of filler-dissolving hyaluronidase.13,16

Notably, patients may not show any signs or symptoms of vascular occlusion during or after the filler procedure or even on the same day. Complaints such as visual disturbance, bruising and a dusky colour change in the skin, along with varying degrees of pain over the impacted areas, may not appear until the next day or later. In the days following the procedure, the presentation can evolve into changes that appear as pustules or blisters, similar to herpes lesions, and then progress to erosion, crusting and eventual scarring. Immediate referral back to the original injector or a qualified clinician for prompt management is essential.

‘DIY’ injectables

Contemporary ‘click-and-collect’ consumer expectations through online marketplaces, such as Amazon and Alibaba, combined with online video tutorials (e.g. YouTube) on how to self-inject botulinum toxin and fillers have created a niche community dabbling in ‘DIY’ injectables.19 Lay DIY injectors report self-administering for the following reasons: the higher cost of services at credentialled facilities, limited access to service facilities and an opportunity to ‘create’ the look they desire.19 There are no reliable estimates of the extent of this unsafe practice, and the paucity of published cases on DIY filler mishaps is likely an underestimate of prevalence as only the worst cases (e.g. intravascular injection) tend to filter through the healthcare system.20 This is a concerning trend, and stronger regulation and targeted education are necessary to minimise these avoidable self-inflicted injuries.

Practice tips for practitioners

Managing patient expectations is important to prevent dissatisfaction from unrealistic patient expectations. This requires appropriate clinical and psychological assessment to ensure that a patient’s requests and wishes are achievable and appropriate. Many patients seek subtle enhancements rather than pronounced alterations, particularly with fillers, that could make them look ‘too different’. Meanwhile, individuals with body dysmorphia have a skewed self-perception and may pursue a pronounced makeover or multiple procedures, only to remain dissatisfied because of unresolved emotional and psychological issues. If body dysmorphia is suspected, the cosmetic injector should liaise or correspond with the patient’s GP to discuss whether referral to a specialist psychologist is necessary. Appropriate clinical assessment is also paramount to ensure that the cosmetic procedures that patients seek are appropriate for their particular cosmetic concerns. Starting cosmetic injections earlier may have a preventative effect and may postpone the need for surgical interventions. However, for those showing pronounced signs of ageing, a surgical referral for a facelift or blepharoplasty (eyelift) might be more appropriate. As with any medical procedure, maintaining comprehensive clinical records, obtaining informed consent and capturing before-and-after images should be standard practice.

Conclusion

Cosmetic injectables, including BoNTA and HA fillers, are regulated prescription products that have come under increased scrutiny by Australian regulatory bodies, particularly around product marketing and procedural glamourisation. Despite their generally safe profile, the use of these injectables may cause serious and less recognised adverse effects, such as blindness and the formation of late-onset nodules. Knowledge of the facial arterial and muscle anatomy is important to help manage these effects. Managing patient expectations realistically, conducting a comprehensive clinical assessment and adhering to ethical and safe practices can ensure optimal outcomes and minimise the risks associated with cosmetic injectables. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Verma: None. Dr Lim is a Board Member of the Australasian Society of Cosmetic Dermatologists; and a Board Member of the Australasian College of Dermatologists. Dr Lim’s partner previously worked for Cryomed, a division of EBOS. Dr Roberts is a Consultant for Allergans and Dermocosmetica. Professor Goodman is a Consultant for Abbvie/Allergan and Galderma; is an Ad Board member for Abbvie/Allergan, Galderma and IBSA; has been a speaker for Abbvie/Allergan; receives consulting fees and payment from Abbvie/Allergan, Galderma and IBSA; has received support for attending meetings for IBSA, L'Oréal and Galderma; is an Advisory Board member for Caliway Pharmaceuticals; and is President of the Australasian Society of Cosmetic Dermatologists.

References

1. Grand View Research. Australia facial injectable market size, share & trends analysis report by procedure type, by application (aesthetics, therapeutics), and segment forecasts, 2024 - 2030. San Francisco, CA: Grand View Research; 2024. Available online at: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/australia-facial-injectables-market-report (accessed May 2024).

2. Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). Non-surgical cosmetic procedures. Sydney: AHPRA; 2024. Available online at: https://www.ahpra.gov.au/Resources/Cosmetic-surgery-hub/Information-for-the-public/Injectables.aspx (accessed May 2024).

3. Carruthers A, Carruthers J, eds. In: Procedures in cosmetic dermatology. 4th ed. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.

4. Alster TS, Harrison IS. Alternative clinical indications of botulinum toxin. Am J Clin Dermatol 2020; 21: 855-880.

5. Kassir M, Gupta M, Galadari H, et al. Complications of botulinum toxin and fillers: a narrative review. J Cosmet Dermatol 2020; 19: 570-573.

6. Skorochod R, Nesher R, Nesher G, et al. Ophthalmic adverse events following facial injections of botulinum toxin A: a systemic literature review. J Cosmet Dermatol 2021; 20: 2409-2413.

7. Alsuhaibani AH, Eid SA. Botulinum toxin injection and tear production. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2018; 29: 428-433.

8. Carruthers J, Carruthers A, eds. Soft tissue augmentation In: Procedures in cosmetic dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.

9. de Wit A, Siebenga PS, Wijdeveld RW, Koopmans PC, van Loghem JAJ. A split-face comparative performance evaluation of injectable hyaluronic acid-based preparations HCC and CPM-HA20G in healthy females. J Cosmet Dermatol 2022; 21: 5576-5583.

10. Bachour Y, Kadouch JA, Niessen FB. The aetiopathogenesis of late inflammatory reactions (LIRs) after soft tissue filler use: a systematic review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2021; 45: 1748-1759.

11. Kablik J, Monheit GD, Yu L, et al. Comparative physical properties of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. Dermatol Surg 2009; 35: 302-312.

12. Goodman GJ, McDonald CB, Lim A, et al. Making sense of late tissue nodules associated with hyaluronic acid injections. Aesthet Surg J 2023; 43: Np438-Np448.

13. Signorini M, Liew S, Sundaram H, et al. Global aesthetics consensus: avoidance and management of complications from hyaluronic acid fillers – evidence- and opinion-based review and consensus recommendations. Plast Reconstr Surg 2016; 137: 961e-971e.

14. Modarressi A, Nizet C, Lombardi T. Granulomas and nongranulomatous nodules after filler injection: different complications require different treatments. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2020; 73: 2010-2015.

15. Kim JE, Sykes JM. Hyaluronic acid fillers: history and overview. Facial Plast Surg 2011; 27: 523-528.

16. Urdiales-Gálvez F, Delgado NE, Figueiredo V, et al. Treatment of soft tissue filler complications: expert consensus recommendations. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2018; 42: 498-510.

17. Kato JM, Matayoshi S. Visual loss after aesthetic facial filler injection: a literature review on an ophthalmologic issue. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2022; 85: 309-319.

18. Sorensen EP, Council ML. Update in soft-tissue filler-associated blindness. Dermatol Surg 2020; 46: 671-677.

19. Rauso R, Nicoletti GF, Zerbinati N, et al. Complications following self-administration of hyaluronic acid fillers: literature review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2020; 13: 767-771.

20. Choi S, Oh BH. Vascular complication caused by self-injected hyaluronic acid filler. Dermatol Surg 2021; 47: 1155-1156.