What’s the diagnosis?

An itchy rash on the face and upper limbs

Case presentation

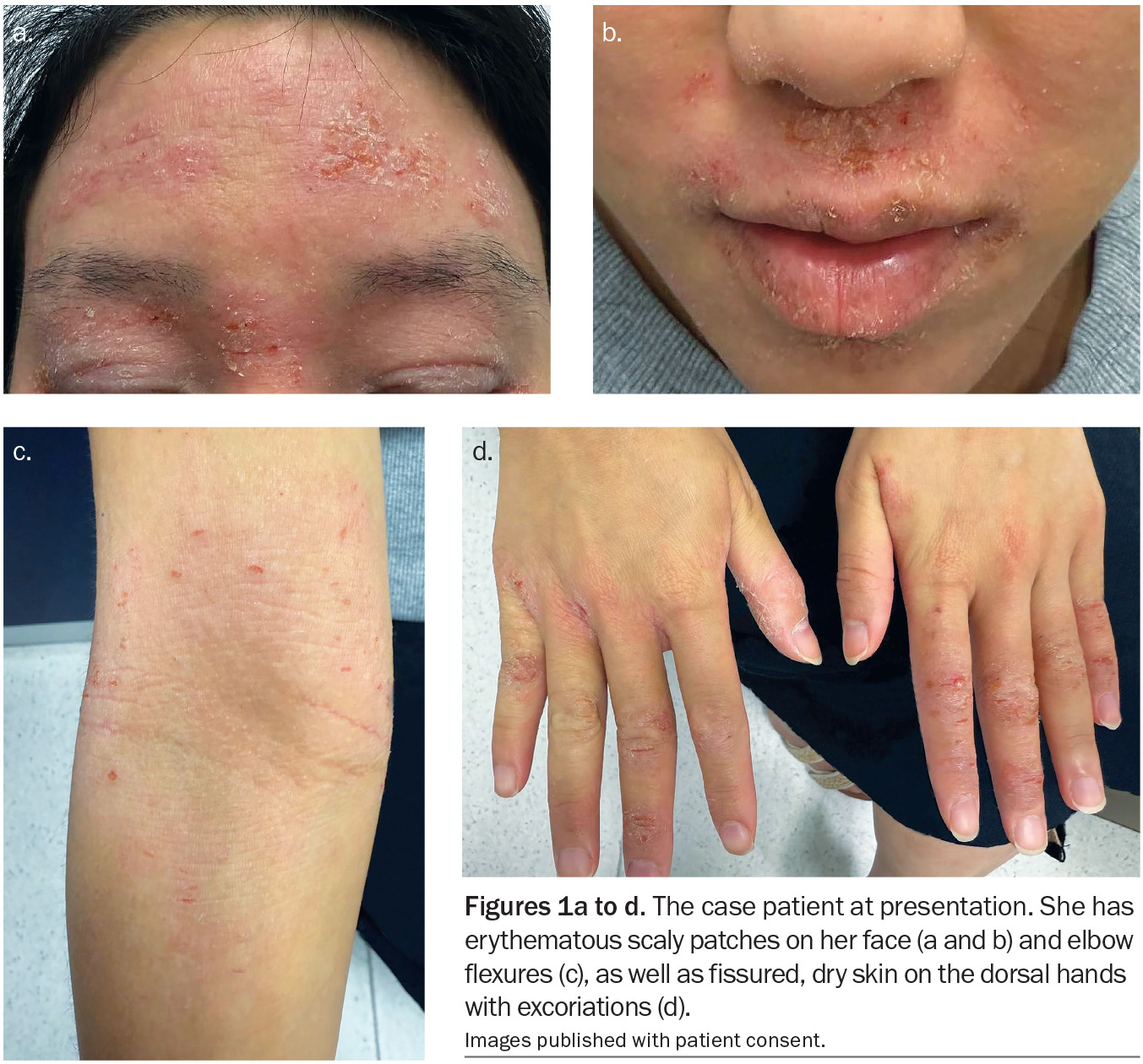

A 24-year-old woman presents with an intensely itchy rash on her face, hands and elbows (Figures 1a to d). She describes a 10-year history of the rash with intermittent flares triggered by stress, environmental allergens such as dust, pollens and animal dander, and cold weather. Her facial skin is dry and red, particularly on the forehead and eyelids as well as the areas around the eyes, nose and mouth. Her hands are dry and cracked and she has pruritic plaques in her elbow flexures. The current flare began three weeks ago after a period of stress at her workplace.

The patient has been applying over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream to the rash, with only mild temporary improvement. She denies use of new cosmetic products or skincare changes. She has been using eyedrops available over-the-counter (naphazoline hydrochloride) for relief of red, congested eyes.

The patient is in otherwise good health but has suffered low mood because of her chronic skin problems. She has a history of childhood asthma and develops seasonal hay fever.

On examination, ill-defined erythematous scaly patches are observed on the patient’s forehead, eyelids and periocular, perioral and perinasal areas. The rash consists of rough, dry plaques with overlying fine scale; there is no sparing around the lips. The eyelids are oedematous and lichenified from chronic scratching. No pustules, comedones, or telangiectasia are seen on the face. The flexural aspects of both elbows show similar erythematous scaly plaques and the dorsal hands both have fissured, dry eczematous skin with excoriations.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory skin condition affecting areas rich in sebaceous glands. Afflicting about 1 to 4% of the general Australian population (pooled global prevalence of about 4.4%), it has a bimodal age distribution with peaks in infancy and in early adulthood.1,2 Seborrhoeic dermatitis is more common in men than women and tends to be more severe in cold, dry climates and in individuals who are immunosuppressed, such as patients with HIV infection or Parkinson’s disease.1,2

The cause of seborrhoeic dermatitis is multifactorial but an inflammatory reaction to proliferation of Malassezia yeasts on the skin is thought to play a central role.1,3 A genetic predisposition, impaired skin barrier and environmental factors (e.g. stress) are contributing factors.2

Seborrhoeic dermatitis typically presents as erythematous patches with greasy scaling.1 Adults develop poorly defined, scaly plaques on the scalp, face (hairline, eyebrows, eyelids, nasolabial folds, ears) and upper trunk.2 The rash may be mildly itchy or asymptomatic. In infants, thick yellow greasy scale on the scalp (cradle cap) is common.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is generally diagnosed clinically on the basis of its characteristic appearance and distribution. Dermoscopy may show dilated vessels with yellowish scale. A biopsy will show spongiosis with superficial perivascular inflammation, but is rarely needed.2,4

For the case patient, the facial location of her rash (especially eyebrow and perinasal areas) may have been suggestive of seborrhoeic dermatitis, but the cubital fossa and hand are atypical locations. In addition, the lesions were intensely pruritic and the rash was dry and lichenified (rather than greasy) – these features were more consistent with a different diagnosis.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis, a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory dermatosis, affects about 2 to 3% of the world’s population.5,6 In some Northern European populations its prevalence is higher (up to 8 to 11%).5 Onset can occur at any age, but there are two incidence peaks: one in young adulthood (second to third decade) and another in middle age (fifth to sixth decade).6

Psoriasis has a strong genetic predisposition and is associated with certain HLA genes. It is an autoimmune-related condition involving dysregulation of the IL-23/Th17 axis, leading to keratinocyte hyperproliferation and chronic inflammation.7 Environmental triggers include streptococcal infection (especially for guttate psoriasis), trauma (Koebner phenomenon), stress, certain medications (lithium, interferon, beta blockers, antimalarials; rapid tapering of prednisone and NSAIDs). Cold weather can also precipitate or worsen psoriasis.7,8

The classic lesions of psoriasis are well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with overlying silvery scale. They often occur on extensor surfaces, such as elbows and knees, as well as the scalp and sacral area.9 Pinpoint bleeding when scale is removed (Auspitz sign) is a characteristic finding. Psoriatic plaques can be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic. Patients may develop nail changes (pitting, onycholysis) and, in some cases, psoriatic arthritis.9,10

The diagnosis of psoriasis is usually clinical, based on the appearance and distribution of lesions. A skin biopsy can confirm psoriasis if the presentation is atypical; histological features include acanthosis with parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum (Munro microabscesses) and thinning of suprapapillary dermis with dilated blood vessels.11

The patient’s lesions were not the classic well-demarcated thick plaques of psoriasis and lacked silvery scale. Instead, her rash was diffuse, poorly defined and markedly pruritic, and there was a predilection for flexures rather than extensor surfaces. These differences make psoriasis unlikely in this scenario.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) refers to a group of autoimmune skin disorders that can present with or without systemic involvement. There are several subtypes, including acute, subacute and chronic.12,13 These conditions primarily affect sun-exposed sites and can cause scarring, dyspigmentation and skin atrophy. The incidence of CLE varies globally, but it is more common in women and people of African, Hispanic and Asian descent.12 CLE can occur at any age, but it typically presents in the second to fourth decades of life. Up to 25% of CLE cases may be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.12

Key contributors to the pathogenesis of CLE include genetic predisposition (certain HLA haplotypes and mutations in complement genes), environmental triggers (such as exposure to ultraviolet light), immune dysregulation (increased interferon activity and autoantibodies, e.g. anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SSB in subacute CLE) and medications (hydrochlorothiazide, terbinafine, TNF-α inhibitors and proton pump inhibitors). Hormones such as vestigial-like family member 3, a transcriptional cofactor that is more highly expressed in female skin, have also been implicated in promoting autoimmune risk by upregulating proinflammatory genes and type I interferon pathways.14

The typical presentation of CLE depends on the subtype. Acute CLE presents as a malar (butterfly) rash characterised by erythema across the cheeks and nasal bridge, sparing the nasolabial folds.15 Subacute CLE presents as annular or papulosquamous erythematous plaques on sun-exposed areas with post-inflammatory dyspigmentation; it is strongly associated with anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies and photosensitivity.12,15 Discoid lupus erythematosus, which is the most common form of chronic CLE, presents as well-demarcated erythematous plaques with follicular plugging, scarring and dyspigmentation.12

CLE is a clinical diagnosis supported by serology (antinuclear antibody [ANA] and extractable nuclear antigen [ENA] testing) as well as histopathology and direct immunofluorescence examination of skin biopsy, if required. Histological features include interface dermatitis with vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer, perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates and dermal mucin deposition.12

For the case patient, the distribution of her rash on the face and arms with erythema and scaling were consistent with of CLE, but pruritus and flexural involvement are not characteristic of this condition. In addition, her absence of photosensitivity or systemic symptoms made CLE less likely.

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common eczematous skin inflammation, resulting from a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction to an external allergen. Sensitisation occurs on first exposure when allergen-specific T cells are activated; subsequent exposure elicits a T cell-mediated immune response causing skin inflammation at the site of contact within 24 to 72 hours.16,17

A 2019 systematic review reported that approximately 20% of people have at least one contact allergy on patch testing.18

Worldwide, the most common cause of allergic contact dermatitis is nickel. Other causes include fragrances, preservatives, dyes, rubber additives and plant resins.18 It is more frequently seen in women than men, which is likely due to greater exposure to cosmetic allergens and jewellery metals. The condition is associated with certain occupational exposures, such as hairdressing (dye allergy) and healthcare work (latex or glove chemical allergy).

Allergic contact dermatitis can present acutely as well-demarcated erythema, oedema and intensely pruritic vesicles or bullae on the site of contact. Over days it may weep and then crust. With chronic or repeated exposure, lesions can become lichenified, dry and fissured, resembling chronic eczema.16 The distribution usually corresponds to the site where the allergen came into contact with the skin; however, in severe cases it may spread further.16

Diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion and supported by the morphology and distribution of the rash. Lesions often have sharply defined borders that reflect the shape or area of exposure, and a detailed history can provide essential clues. Patch testing remains the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis.19

An eczematous rash on the face or hands caused by allergic contact dermatitis causing typically correlates with a specific exposure. The case patient reported using eyedrops that contained benzylalkonium chloride, which were suspected to be contributing to her presentation, but the widespread nature and endogenous pattern (widespread facial involvement, hands and cubital fossa) suggested an underlying dermatosis.

Atopic dermatitis

This is the correct diagnosis. Atopic dermatitis (also known as eczema or atopic eczema) is a chronic, relapsing inflammatory skin disease. The term ‘atopic’ reflects the tendency for patients to have IgE-mediated allergies or other atopic conditions such as asthma or allergic rhinitis.20

Atopic dermatitis is one of the most common skin disorders, with onset usually being in the first five years of life.21 It affects up to 15 to 20% of children and about 7 to 10% of adults globally.21,22 Many children experience improvement by adolescence but a significant number continue to have lifelong or recurring disease.22 Onset can also occur in adulthood.

Clinically, atopic dermatitis lesions are erythematous, ill-defined, scaly patches or plaques that can be acute (wet and vesicular) or chronic (dry, lichenified, thickened from scratching).23 Pruritus is a hallmark symptom, driving the scratching that exacerbates the rash.

The typical morphology and distribution of the condition varies with age.24

- Infants (birth to 2 years): Dermatitis often affects the cheeks and face, scalp and extensor surfaces of the limbs. It may be weepy and vesicular. The diaper area is usually spared (due to moisture retention).

- Children (2 to 12 years): Dermatitis tends to become more flexural, affecting the antecubital and popliteal fossae, neck, wrists, ankles and feet. Lesions are often dry, lichenified and excoriated from chronic scratching.

- Adolescents and adults (>12 years): Dermatitis may remain localised to flexures but often involves the hands, eyelids and periorificial areas of the face and can become more generalised. Chronic hand dermatitis is common in adults because of frequent exposure to irritants across an impaired skin barrier. Nummular (coin-shaped) lesions may also be seen.

The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) is a validated scoring system used to evaluate the extent and severity of atopic dermatitis, with scores ranging from 0 (no disease) to 72 (extensive and severe disease).25 The EASI is widely used in both research settings and clinical practice to monitor disease progression and treatment response.

Atopic dermatitis arises from an interplay of genetic predisposition, epidermal barrier disruption, immune system dysregulation and environmental factors. Loss-of-function mutations in the filaggrin gene, which encodes a protein that is crucial for skin barrier integrity and hydration, are common in patients with atopic dermatitis and the strongest known genetic risk factor for the condition.26,27 Immunologically, atopic dermatitis is characterised by an overactive T helper 2 (Th2) response in acute lesions. There is also involvement of the Th17 and Th22 pathways, especially in chronic disease or adult AD. This immune dysregulation leads to inflammation and itch, and the itch–scratch cycle then causes further damage to the skin barrier.26

Environmental factors play a significant role in triggering flares. Common triggers include harsh soaps and detergents, low humidity (especially dry cold weather), overheating and sweating, rough wool fabrics, psychological stress and airborne allergens (e.g. dust mite, pollens). Many patients notice flares with viral infections. Food allergy is primarily a trigger in infants with severe eczema, but occurs occasionally in older patients.28 Microbial colonisation is another factor: Staphylococcus aureus colonises the skin of most patients with atopic dermatitis and can exacerbate inflammation by secreting toxins (superantigens) and inducing infection.26

Atopic dermatitis has a significant impact on quality of life. Chronic itch can lead to loss of sleep, irritability and difficulty concentrating. A visible rash, especially on the face, can cause psychological stress. Atopic dermatitis is associated with higher rates of anxiety and depression.29

Diagnosis

Atopic dermatitis is primarily a clinical diagnosis, which is supported by formal criteria.30-33 In practice, the combination of chronic itchy dermatitis in flexural or other typical sites and onset in childhood is usually sufficient for diagnosis. A skin biopsy is not usually needed when the clinical picture is classic but may be performed if the presentation is atypical or other diagnoses need to be excluded. The histopathological features of eczema are nonspecific and include spongiotic dermatitis (intercellular oedema in the epidermis) with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate. In chronic lesions there is acanthosis (epidermal thickening).34

Investigations for specific allergies (e.g. radioallergosorbent tests, skin-prick tests) can be undertaken if a food trigger is strongly suspected. These are mainly used in infants with severe eczema.

Management

Management of atopic dermatitis requires a multifaceted approach. The goals are to reduce symptoms (itch, rash), prevent flares and treat any complications, such as infection. A stepped approach tailored to disease severity is recommended, as outlined in the Australian guidelines.35 By adhering to these management principles, most patients with atopic dermatitis can achieve good control of their disease. Referral to a dermatologist or immunologist is indicated for patients who are not responding to treatment, have frequent infections or are being considered for advanced therapies.

General skin care and trigger avoidance

General skin care for patients with atopic dermatitis includes application of moisturiser at least twice daily. Patients should select personal care products that do not contain fragrances or dyes. To avoid skin drying and irritation, baths and showers should be warm (not hot) and of short duration (5 to 10 minutes).

Topical anti-inflammatory therapy

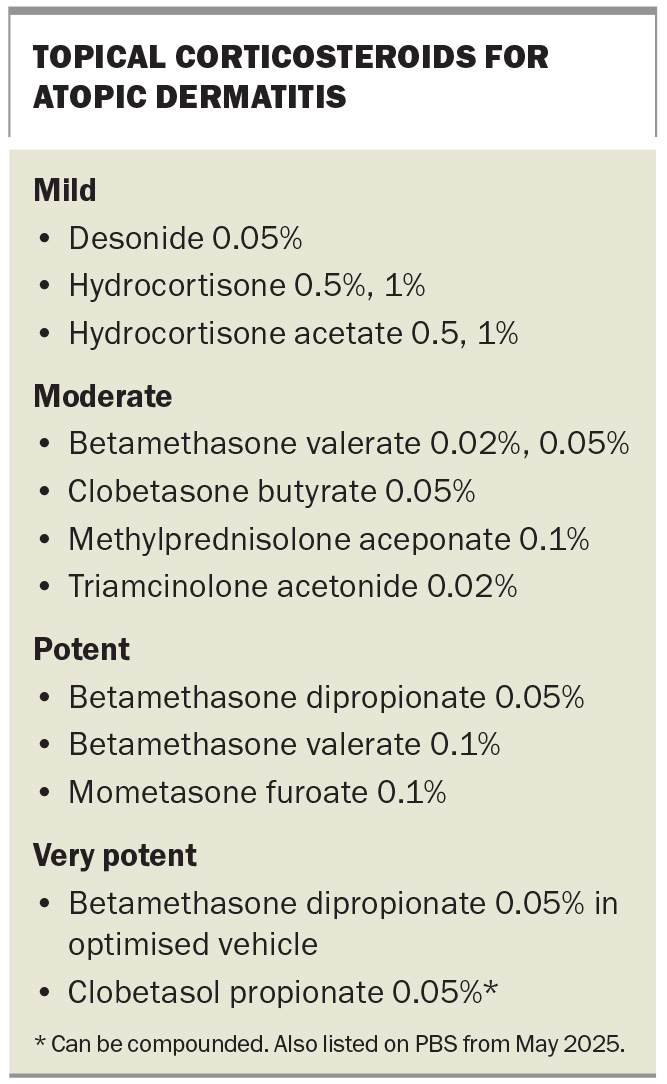

Topical corticosteroids are the first-line pharmacological therapy for active flares of atopic dermatitis, and the potency of the corticosteroid should be tailored to disease severity and site.35,36 Topical corticosteroids used to treat atopic dermatitis are listed in the Box. For the face and intertriginous areas, low-potency corticosteroids are preferred because of the risk of skin atrophy; for areas with thicker skin, such as the limbs and trunk, medium-to-high potency corticosteroids can be used. Topical corticosteroids are typically applied once or twice daily during flares as a short course (e.g. one to two weeks of regular use) until lesions improve, then tapered off. Patients should be educated about the different potencies of topical corticosteroid products and their appropriate use – it is important that they understand which product is suitable for different body sites and avoid high-potency corticosteroids on sensitive areas such as the face, groin and axillae. Patients should also be instructed on use of the fingertip unit to measure the quantity of cream or ointment to apply (one fingertip unit covers about 2% of body surface area).37

Topical calcineurin inhibitors are corticosteroid-sparing agents that are particularly useful for treating delicate sites, such as the eyelids, face, neck and skinfolds.36 These agents reduce inflammation by inhibiting T-cell activation without the side effects of topical corticosteroids and can be used for long-term maintenance treatment. Pimecrolimus 1% cream is listed on the PBS for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Topical tacrolimus is not listed on the PBS and currently requires compounding as a 0.03% or 0.1% ointment.

Crisaborole 2% ointment, a topical phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, has been approved by the TGA for treatment of mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis in patients aged 2 years and older. It is less frequently used in Australia because of cost and access issues but may be considered as another nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory treatment option.38

Adjunctive therapies

Adjunctive therapies for acute flares of atopic dermatitis include bleach baths, which help to reduce bacterial colonisation and the risk of secondary infection. These are typically prepared to achieve a concentration of 0.005% sodium hypochlorite (e.g. half a cup of household bleach in a full tub of bathwater for adults). Wet dressings are used for enhancing the effect of topical corticosteroids or emollients; they also cool inflamed skin, reduce pruritus and serve as a protective barrier against scratching.

Antihistamines (e.g. cetirizine, loratadine) may provide some benefit for improving itch.36 However, they have limited efficacy because the itch caused directly by eczema is not histamine-mediated and so benefit is limited.

If there are signs of bacterial infection (e.g. pustules, honey-coloured crusts or cellulitis), a short course of systemic antibiotics active against S. aureus (such as flucloxacillin or cephalexin) is indicated. In milder infection, topical antibiotics (e.g. mupirocin ointment) can be used on localised areas.36

Phototherapy helps reduce inflammation and can improve skin barrier function.39 For patients with atopic dermatitis, narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy can be very effective if topical treatments are insufficient or widespread areas are involved.

Systemic therapies

For patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis that is unresponsive to topical treatments, systemic immunomodulatory therapies may be considered. Ciclosporin is a fast-acting traditional immunosuppressant approved by the TGA for up to two years in patients with severe atopic dermatitis and listed on the PBS.36 It can significantly reduce disease severity but carries risks of nephrotoxicity and hypertension, limiting long-term use. Other traditional oral immunosuppressants, such as methotrexate, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil, may offer corticosteroid-sparing benefits (off-label use in atopic dermatitis); they are effective for atopic dermatitis but evidence supporting their efficacy is less robust than for their use in conditions such as psoriasis.36,40 Regular blood monitoring is required to detect potential adverse effects, including hepatotoxicity and myelosuppression.

In recent years, targeted biologic therapies have revolutionised atopic dermatitis treatment. Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin IL-4 and IL-13 signalling, was the first biologic therapy to be approved. Clinical trials have demonstrated that about two-thirds of patients achieve a 75% improvement (EASI-75) by week 16.36,41,42 Dupilumab is listed on the PBS for patients aged 12 years and older with severe disease who have failed to respond to topical therapies.36 Dupilumab is administered via subcutaneous injection every two weeks and has a favourable safety profile, with conjunctivitis being the most commonly reported adverse effect.

Another biologic therapy, lebrikizumab, was approved by the TGA in May 2024 for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Lebrikizumab targets IL-13 and has demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials.43 It is not currently listed on the PBS.

In addition, two Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are now approved for atopic dermatitis.36 They have shown a reduction in the severity and extent of atopic dermatitis in as little as two weeks.44 Upadacitinib is indicated for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults and adolescents aged 12 years and older and is listed on the PBS (authority required) for severe atopic dermatitis.45 Abrocitinib is indicated for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults and is not currently listed on the PBS.46 JAK inhibitors carry warnings for potential serious side effects (e.g. infection, laboratory abnormalities, thromboembolic risk, cardiovascular and malignancy risk), and, therefore, careful patient selection and monitoring are required.36

In NSW, a number of pharmacists are participating in dermatology phase of the NSW Pharmacy Trial, an initiative that allows trained pharmacists to assess and manage patients with certain skin conditions, including mild to moderate atopic dermatitis, until 31 August 2025. Further details about the trial, including patient eligibility criteria and a list of participating pharmacies, are available on the NSW Health website (https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/pharmaceutical/Pages/cp-pharmacists-Information.aspx).

Outcome

The case patient’s presentation was classic for atopic dermatitis with infection, with a calculated EASI score of 26. A skin swab was taken and confirmed the presence of S. aureus. It was suspected that allergic contact dermatitis was exacerbating the eyelid dermatitis and so she was referred for patch testing, which confirmed allergy to the eyedrop preservative. She was diagnosed with atopic dermatitis with S. aureus infection and allergic contact dermatitis caused by benzylalkonium chloride.

The patient was educated about the conditions and the importance of trigger avoidance. She was advised to use a soap-free cleanser and to apply a thick, fragrance-free moisturiser to her face and whole body twice daily. To treat the secondary infection, cephalexin 500 mg three times daily was initiated with mupirocin ointment three times daily for two weeks. She was also given instructions for preparing a dilute bleach bath (approximately twice a week) to reduce bacterial colonisation. She was advised to cease using the eyedrops and to avoid products containing benzylalkonium chloride in the future.

The patient was prescribed hydrocortisone 1% ointment for her face (twice daily for up to two weeks) and mometasone furoate 0.1% ointment for her elbows and hands (once daily for one to two weeks, then as needed). She then continued treatment with pimecrolimus 1% cream on her eyelids and perioral area, to maintain long-term control. An oral sedating antihistamine (hydroxyzine 25 mg at night) was given to help break the itch-scratch cycle and improve sleep.

At her four-week follow-up visit, the patient’s skin had improved considerably and the secondary infection had resolved. However, she continued to experience moderate to severe disease, particularly affecting her face, hands and cubital fossa dermatitis (EASI>20). She satisfied PBS eligibility criteria for dupilumab therapy and commenced treatment. An action plan was developed for managing active flares.

Over the next six months, the patient’s dermatitis remained well controlled with only occasional mild flares, typically during periods of stress, which have been managed with short courses of topical corticosteroids (two to three days) as outlined in her action plan. She continues to use regular emollients and remains under dermatologist care. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Polaskey MT, Chang CH, Daftary K, Fakhraie S, Miller CH, Chovatiya R. The global prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2024; 160: 846-855.

2. Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician 2015; 91: 185-190.

3. Kim GK. Seborrheic dermatitis and Malassezia species: how are they related? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2009; 2: 14-17.

4. Borda LJ, Perper M, Keri JE. Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Dermatolog Treat 2019; 30: 158-169.

5. Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol 2013; 133: 377-385.

6. Damiani G, Bragazzi NL, Karimkhani Aksut C, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of psoriasis: results and insights from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021; 8: 743180.

7. Yan D, Gudjonsson JE, Le S, et al. New frontiers in psoriatic disease research, Part I: genetics, environmental triggers, immunology, pathophysiology, and precision medicine. J Invest Dermatol 2021; 141: 2112-2122.e3.

8. Lee EB, Wu KK, Lee MP, Bhutani T, Wu JJ. Psoriasis risk factors and triggers. Cutis 2018; 102: 18-20.

9. Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, Barker JNWN. Psoriasis. Lancet 2021; 397: 1301-1315.

10. Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 251-265.e19.

11. Feldman SR. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. In: UpToDate, Givens J, Ofori AO (eds), Wolters Kluwer; 2024. Available online at: https://www.uptodate.com (accessed May 2025).

12. Vale ECS. Garcia LC. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a review of etiopathogenic, clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol 2023; 98: 355-372.

13. Chen KL, Krain RL, Werth VP. Advancing understanding, diagnosis, and therapies for cutaneous lupus erythematosus within the broader context of systemic lupus erythematosus. F1000Res 2019; 8: 332.

14. Little AJ, Vesely MD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: current and future pathogenesis-directed therapies. Yale J Biol Med 2020; 93: 81-95.

15. Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2013; 27: 391-404.

16. Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, Pootongkam S, Nedorost S, Brod B. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74: 1029-1040.

17. Gober MD, Gaspari AA. Allergic contact dermatitis. Curr Dir Autoimmun 2008; 10: 1-26.

18. Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP, Johansen JD. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis 2019; 80: 77-85.

19. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician 2010; 82: 249-255.

20. Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018; 4: 1.

21. Bylund S, Kobyletzki LB, Svalstedt M, Svensson A. Prevalence and incidence of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100: adv00160.

22. Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy. Eczema (atopic dermatitis). 2024. Available online at: https://www.allergy.org.au/patients/skin-allergy/eczema (accessed May 2025).

23. Leung DY, Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2003; 361: 151-160.

24. Chatrath S, Silverberg JI. Phenotypic differences of atopic dermatitis stratified by age. JAAD Intern 2023; 11: 1-7.

25. Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, Cherill R, Tofte SJ, Graeber M; the EASI Evaluator Group. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol 2001; 10: 11-18.

26. Sroka-Tomaszewska J, Trzeciak M. Molecular mechanisms of atopic dermatitis pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22: 4130.

27. Gao PS, Rafaels NM, Hand T, et al. Filaggrin mutations that confer risk of atopic dermatitis confer greater risk for eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 124: 507-513.e7.

28. Jones SM. Triggers of atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am 2002; 22: 55-72.

29. Chidwick K, Busingye D, Pollack A, et al. Prevalence, incidence and management of atopic dermatitis in Australian general practice using routinely collected data from MedicineInsight. Australas J Dermatol 2020; 61: e319-e327.

30. Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol 1980; 92: 44–47.

31. Williams HC, Burney PG, Hay RJ, et al. The U.K. Working Party’s Diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. I. Derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 1994; 131: 383-396.

32. Thyssen JP, Andersen Y, Halling AS, et al. Strengths and limitations of the United Kingdom Working Party criteria for atopic dermatitis in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: 1764-1772.

33. De D, Kanwar A, Handa S. Comparative efficacy of Hanifin and Rajka’s criteria and the UK working party’s diagnostic criteria in diagnosis of atopic dermatitis in a hospital setting in North India. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006; 20: 853-859.

34. Tokura Y, Yunoki M, Kondo S, Otsuka M. What is “eczema”? J Dermatol 2025; 52: 192-203.

35. Atopic dermatitis. In: Therapeutic guidelines: dermatology. Melbourne; TG; 2022. Available online at: https://tg.org.au (accessed May 2025).

36. Ross G. Treatments for atopic dermatitis. Aust Prescr 2023; 46: 9-12.

37. Topical steroids – how much do I use? In: Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide SA: AMH; 2017. Available online at: https://resources.amh.net.au/public/fingertipunits.pdf (accessed May 2025).

38. Schlessinger J, Shepard JS, Gower R, et al. Safety, effectiveness, and pharmacokinetics of crisaborole in infants aged 3 to open-label study (CrisADe CARE 1). Am J Clin Dermatol 2020; 21: 272-284.

39. Pugashetti R, Koo J. Phototherapy in pediatric patients: choosing the appropriate treatment option. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2010; 29: 115-120.

40. Garritsen FM, van den Heuvel JM, Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, Maitland-van der Zee AH, van den Broek MPH, de Bruin-Weller MS. Use of oral immunosuppressive drugs in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in the Netherlands. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 1336-1342.

41. Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 2287-2303. 20170504.

42. Ariëns LFM, van der Schaft J, Spekhorst LS, et al. Dupilumab shows long-term effectiveness in a large cohort of treatment-refractory atopic dermatitis patients in daily practice: 52-Week results from the Dutch BioDay registry. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 84: 1000-1009.

43. Silverberg JI, Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, et al; ADvocate1 and ADvocate2 Investigators. Two phase 3 trials of lebrikizumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2023; 388: 1080-1091.

44. Mikhaylov D, Ungar B, Renert-Yuval Y, Guttman-Yassky E. Oral Janus kinase inhibitors for atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2023; 130: 577-592.

45. Silverberg JI, de Bruin-Weller M, Bieber T, et al. Upadacitinib plus topical corticosteroids in atopic dermatitis: Week 52 AD Up study results. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022; 149: 977-987.e914.

46. Iznardo H, Esther Roé E, Serra-Baldrich E, Puig L. Efficacy and safety of JAK1 Inhibitor abrocitinib in atopic dermatitis. Pharmaceutics 2023; 15: 385.