Atopic dermatitis: new and emerging treatments

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic relapsing and remitting disease. Patients typically receive treatment with counselling, trigger avoidance, emollients, wet dressings and topical corticosteroids. Conventional systemic agents may be required for severe disease but are often associated with significant adverse events. Recently, the treatment landscape for these patients has changed dramatically with the PBS listing of two targeted systemic treatments: dupilumab and upadacitinib. Other emerging treatments are on the horizon, offering promising options for those with severe recalcitrant disease.

Correction

A correction for this article appears in the May 2025 issue of Medicine Today and is available here. The online version and the full text PDF of this article have been corrected.

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common chronic inflammatory skin disorder worldwide, resulting from skin barrier disruption and a genetic predisposition.

- The mainstay of treatment for mild-to-moderate AD includes topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors and trigger avoidance.

- Conventional treatment of moderate-to-severe AD includes phototherapy and systemic immunosuppression.

- Novel systemic treatments that are PBS listed for moderate-to-severe AD include dupilumab (a human monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signalling) and upadacitinib (a Janus kinase-1 selective small molecule inhibitor).

- Emerging targeted treatments offer promising options for patients with AD who have severe recalcitrant disease.

Atopic dermatitis (AD), also known as eczema, is the most common inflammatory skin condition worldwide, affecting about one in 10 individuals. It is a chronic relapsing and remitting condition seen in all age groups, although it tends to begin in infancy within the first year of life.1 About 30% of infants and 10% of adults experience AD.1-3 AD is often clustered with other allergic hypersensitivity diseases (allergic rhinitis and asthma, often known as the atopic triad), which all have similar mechanisms of pathogenesis.4 Several longitudinal studies also provide evidence to support the atopic march – that is, the progressive development of AD, food allergy, allergic rhinitis and asthma throughout childhood.5-7

Untreated symptomatic AD can have a negative impact on patients’ quality of life. The unrelenting itch-scratch cycle leads to sleep disturbance and chronic fatigue. Continuous itch affects concentration and school performance in children. The mental health comorbidities of AD (e.g. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, conduct disorder and autism) are well established.8-10 Importantly, school performance is compromised by chronic fatigue, behavioural issues and absenteeism, which severely impacts future life courses. Assertive proactive management of AD is paramount.

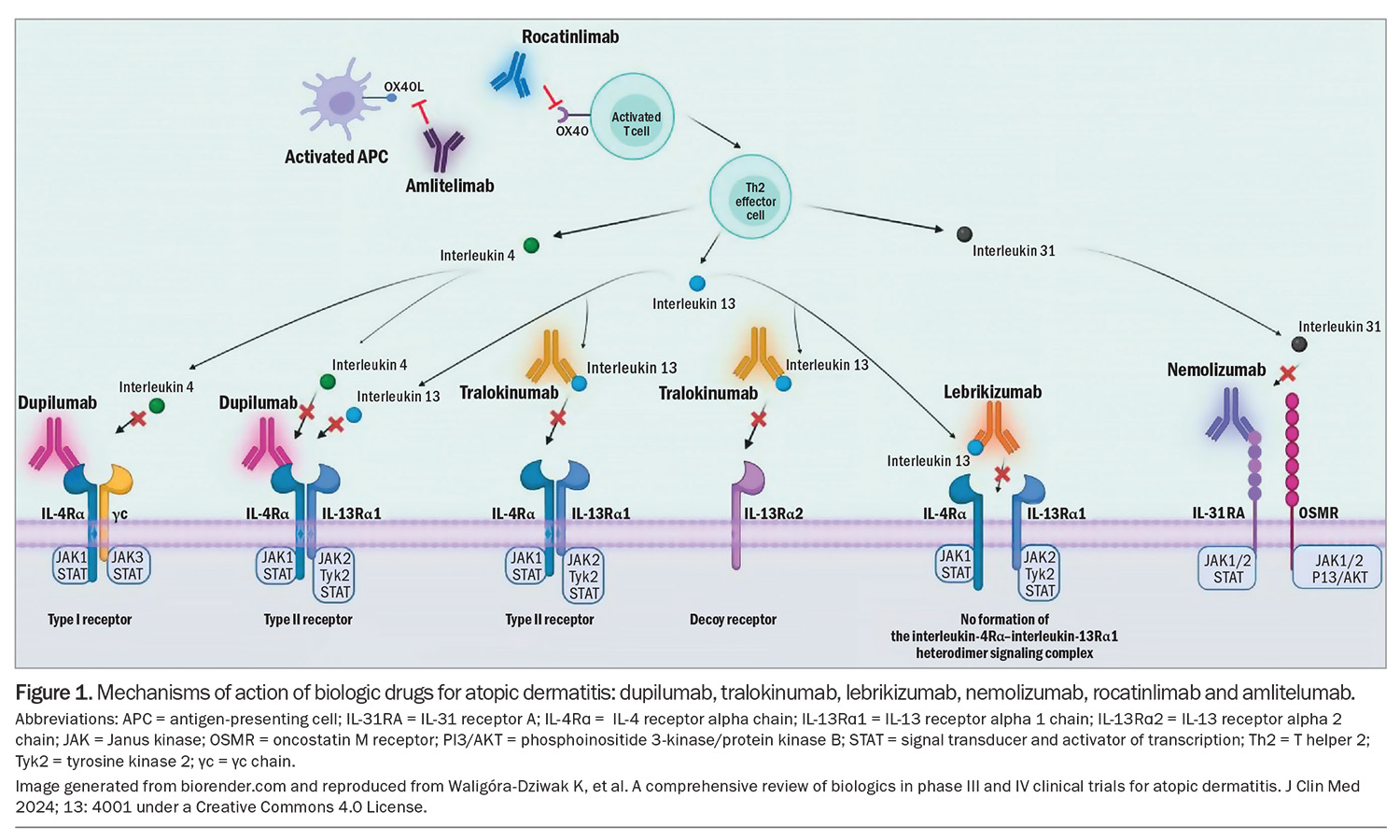

The past decade has seen an increase in advanced therapeutic options becoming available for AD in Australia through clinical trials and more recently listed on the PBS. This article provides an overview of treatment option pathways, which includes new topical and systemic agents and those on the near horizon. Many of these emerging therapies have surpassed phase 3 clinical trials and are already in use for patients overseas with chronic severe AD (Figure 1).11-16

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of AD is complex and multifactorial. AD is a result of both genetic and environmental factors and immune system dysregulation.17,18 Evidence to date suggests that AD is driven by an overactive T helper 2 (Th2) response. This Th2 dominance leads to the production of various cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-13 and IL-31, which contribute to a dysregulated inflammatory response, contributing to skin barrier disruption.17 In response to the compromised skin barrier, keratinocytes produce cytokines such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin, IL-25 and IL-33, which further augments the Th2 response. These inflammatory cytokines also orchestrate the itch sensation by activating cutaneous sensory nerve fibres.1,17

Together, this heightened inflammatory cycle reduces the expression of filaggrin that maintains skin barrier integrity. There is a well-established association between filaggrin mutations and AD, although this is not a causal link, as many patients with filaggrin mutations do not develop AD.17,18 Reduced levels of expression of other components of the epidermis, such as loricrin, involucrin and ceramides, also contribute to the skin barrier deficits that are a hallmark feature of AD.17,19

The impaired skin barrier in AD allows for increased transepidermal water loss, enabling allergens to enter more easily, triggering immunoglobulin E sensitisation.19,20 Triggers for AD can include common allergens such as food, dust mites, environmental allergens (e.g. pollen, grass and mould), irritants (e.g. chlorine, sex hormones, latex) and even changes in weather can trigger an eczema flare.20,21 A disrupted skin barrier also provides a portal for pathogen entry. Secondary skin infections with Staphylococcus aureus and herpes simplex virus further disrupt the skin barrier and further exacerbate AD.20,21

Clinical presentation

AD is generally a clinical diagnosis; however, the clinical presentation of AD varies tremendously. Infants can present with AD on the face and there can be extensor involvement such as on the trunk or back.22,23 However, in adolescents and adults, AD typically presents over flexural areas such as the antecubital and popliteal fossae. Flare-ups of AD can present as intensely pruritic, erythematous, weeping oedematous lesions sometimes associated with crusting. Erosions and excoriations are common, and lichenification or thickening of the skin is a sign of disease chronicity.19,22,23

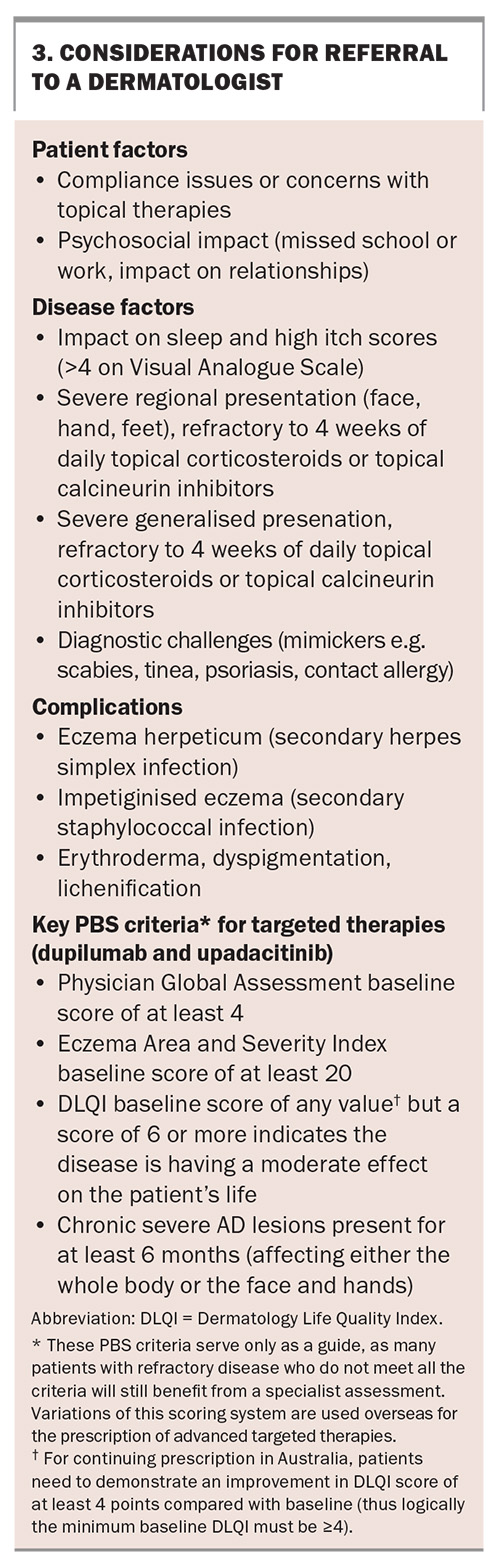

Disease severity scales most relevant to healthcare practitioners in Australia are the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) and Physician Global Assessment (PGA). A minimum rating on these two scales (a baseline EASI of at least 20 and PGA of 4) is required for a PBS subsidy if considering a patient for treatment with an advanced targeted therapy. Other scales have been validated and used in research settings including the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index and the Six Area, Six Sign Atopic Dermatitis (SASSAD) severity score that aims to objectively describe the clinical features of AD. To measure the impact of AD on sleep, mood and quality of life, the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure and Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI) severity scale have been developed.19 For prescribing new targeted therapies in Australia, the DLQI score is required at baseline and is then repeated with each continuous prescription application.

Treatment

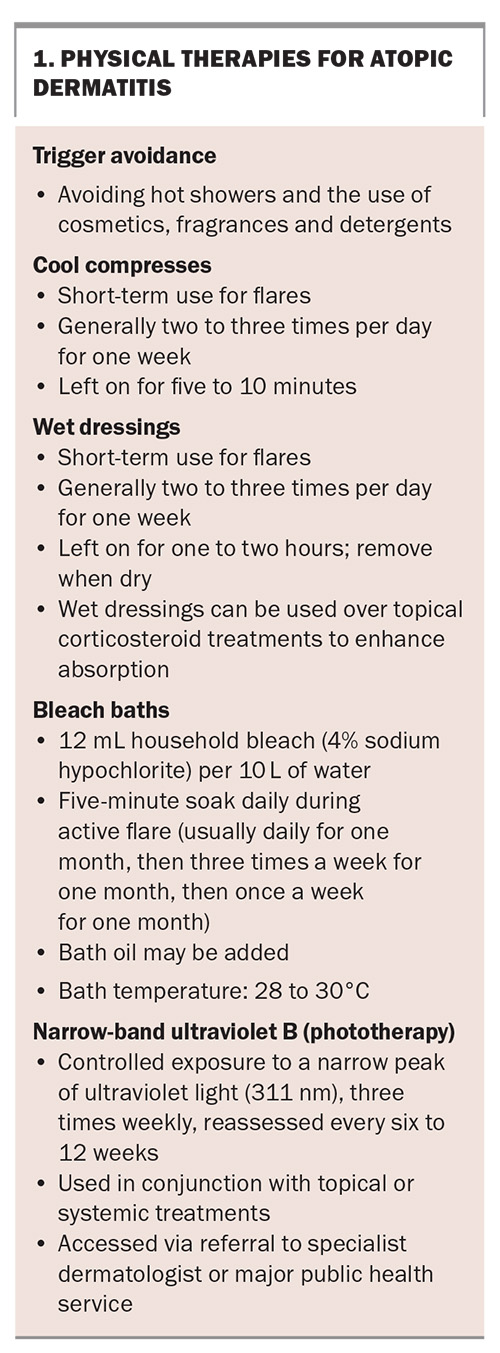

Physical therapies and antibiotics

AD is a relapsing disease. General management recommendations for patients with AD include avoiding irritants such as perfumed products and avoiding exposure to triggers (Box 1).1,24 Moisturising at least twice daily is recommended to maintain the integrity of the skin barrier.19,25 Daily bathing or luke warm showers are recommended to reduce bacterial skin load and are limited to a five-minute duration to avoid skin flares.1,19,24,25 Wet dressings may reduce skin irritation and protect the skin from further trauma but can be cumbersome and time consuming to apply and cause irritation if left overnight.1,25-27 Bleach baths may be recommended to avoid secondary skin infections.1,23,25,26,28 Other physical therapies, such as controlled exposure to narrow-band ultraviolet light therapy, are also considered for AD because of their immunosuppressive effects and ability to enhance the epidermal barrier.24

AD-affected skin can be colonised by S. aureus; therefore, a positive culture from a swab alone cannot differentiate between colonisation and active infection. The decision to treat with systemic antibiotics depends on the clinical relevance, ideally with antimicrobial sensitivities confirmed through culture.1,29 Skin swabs (viral and bacterial) are recommended in circumstances where a secondary skin infection is suspected, to confirm the diagnosis and guide treatment choice.

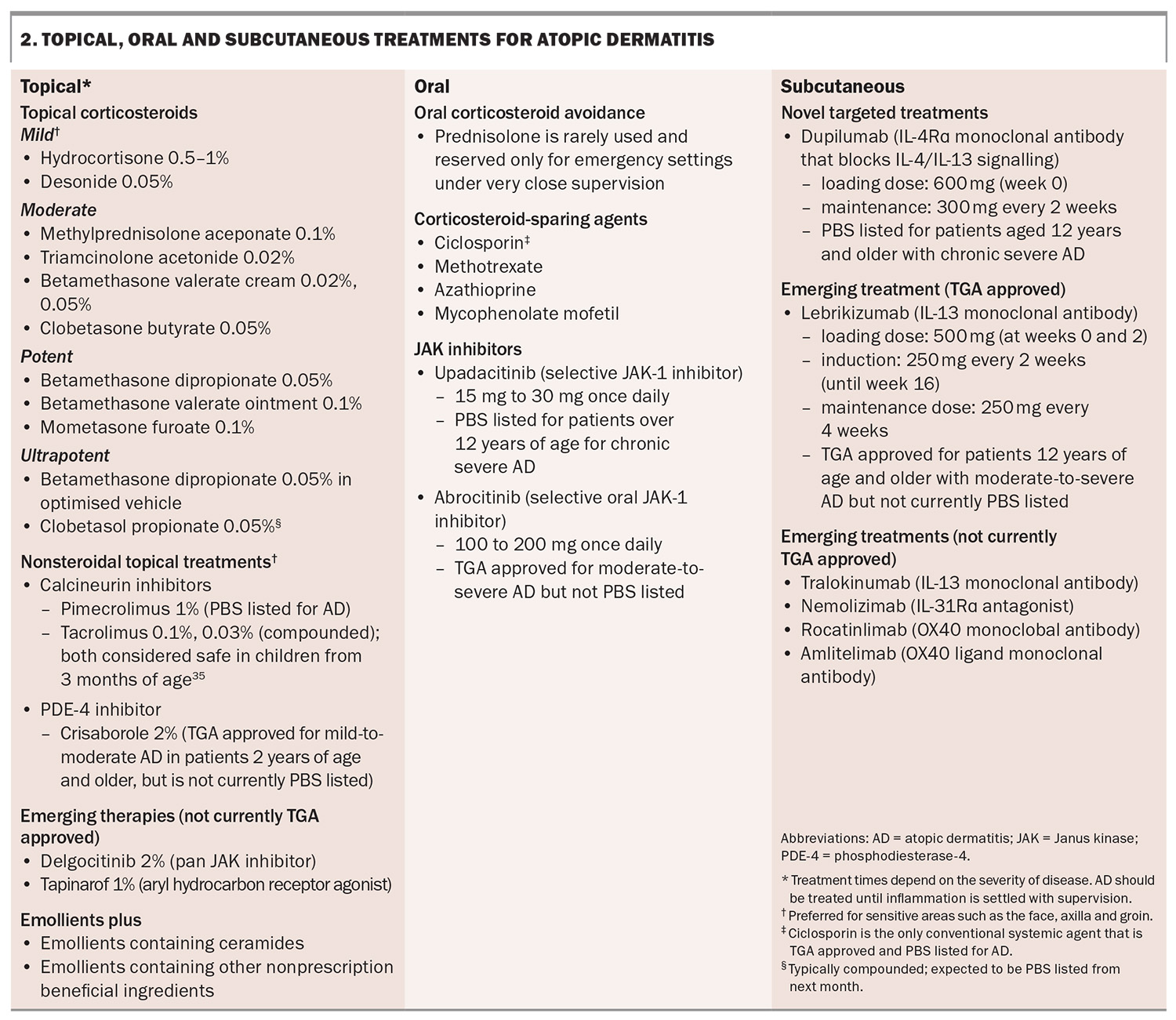

Topical corticosteroids

The mainstay of treatment for AD is the use of topical corticosteroids to reduce inflammation (Box 2).2 The recommended potency of topical corticosteroids depends on the severity and location of the AD. A mild-potency topical corticosteroid is recommended for the face and flexures (e.g. axilla, inframammary, inguinal, cubital or popliteal fossa, genitals) and high potency for thickened, lichenified areas and the palms and soles.1 The potency of corticosteroids is well documented.30 Topical corticosteroids can be applied directly onto skin, or in conjunction with emollients, which are generally applied over topical corticosteroids on inflamed skin.

Clobetasol propionate, the most ultrapotent topical corticosteroid, typically requires compounding, but it is expected to be listed on the PBS, as a 30 g cream and ointment, next month.

Long-term inappropriate use of corticosteroids can lead to skin atrophy, striae, rosacea, telangiectasias and purpura.30 A standard unit used for topical corticosteroid application is the fingertip unit (FTU), which covers the area of two adult hands (i.e. 1 FTU = 0.5 g = 2 palms = 2% of an adult’s body surface area).31,32 The recommended FTUs for adequate effectiveness is well documented.31,32 However, there is a plethora of misinformation about the safety of topical corticosteroids in the media leading to a suboptimal treatment response.33 Reassurance and regular clinical reviews can help overcome treatment barriers.

It is important to select an appropriate base for the topical therapy. Creams are reserved for hair-bearing areas or patient comfort, whereas ointments will increase the topical steroid potency and minimise stinging (thus prescribed for severe flares with major excoriations).

Alternative topical therapies to corticosteroids

Alternative topical therapies to corticosteroids for AD available in Australia are calcineurin inhibitors and crisaborole.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors include tacrolimus ointment (0.03% and 0.1% strengths) and pimecrolimus cream (1% strength). These topical calcineurin inhibitors are naturally produced by Streptomyces bacteria and inhibit T-cell activation, reducing the inflammatory response in AD.34 Topical pimecrolimus 1% is PBS listed for the treatment of AD and is safe to use in sensitive areas such as the eyelids and face in children over the age of 3 months.35 To date, access to topical tacrolimus requires compounding in Australia but the 0.1% tacrolimus ointment is TGA approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD, and is due for release soon.

Crisaborole 2% is a nonsteroidal topical ointment that inhibits the activity of phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4), the levels of which are elevated in patients with AD. The reported barriers are cost and tolerability.36 It is approved by the TGA for the treatment of mild-to-moderate AD in patients 2 years of age and older; however, it is not currently PBS listed (available for purchase in 60 g at a nonsubsidised private price).

Oral corticosteroids and conventional systemic agents

Oral corticosteroids are rarely required for management of severe AD. Patients with a severe flare can be managed with wet dressings and must be prescribed sufficient quantities of topical therapies. Moreover, these patients require a prompt review for initiation of a systemic therapy. Corticosteroid-sparing agents, such as methotrexate and ciclosporin, may be considered; however, with the increasing availability of targeted treatments, these systemic treatments are no longer the mainstay of treatment for severe AD because of their potential for severe life-threatening side effects (e.g. myelosuppression and hepatotoxicity with methotrexate; and hypertension and renal failure with ciclosporin).37

Novel targeted therapies approved and PBS subsidised for use in Australia

Patients with severe refractory cases of AD may be referred to a dermatologist to access novel systemic treatments. Practical considerations when referring patients to dermatologists for more advanced therapies are outlined in Box 3.

Dupilumab

Dupilumab is a human monoclonal antibody that binds IL-4Rα and inhibits signalling mediated by IL-4 and IL-13, key drivers of the inflammatory response of a variety of Th2-mediated diseases, including AD, asthma, rhinosinusitis, nasal polyposis and eosinophilic oesophagitis.38 It is administered fortnightly as a subcutaneous injection (300 mg, after a loading dose of 600 mg). It is generally well tolerated. Commonly reported side effects include conjunctivitis, injection-site reactions, nasopharyngitis, headache and oral herpes simplex virus reactivation.39 Rarer adverse effects that have been reported include seronegative arthritis and enthesitis, de novo psoriasis, paradoxical head and neck dermatitis and worsening of alopecia areata.40-42 Recent literature has raised the possibility of an increased risk of cutaneous T cell lymphoma, although further research is needed as reported data appear to be inconclusive.43,44

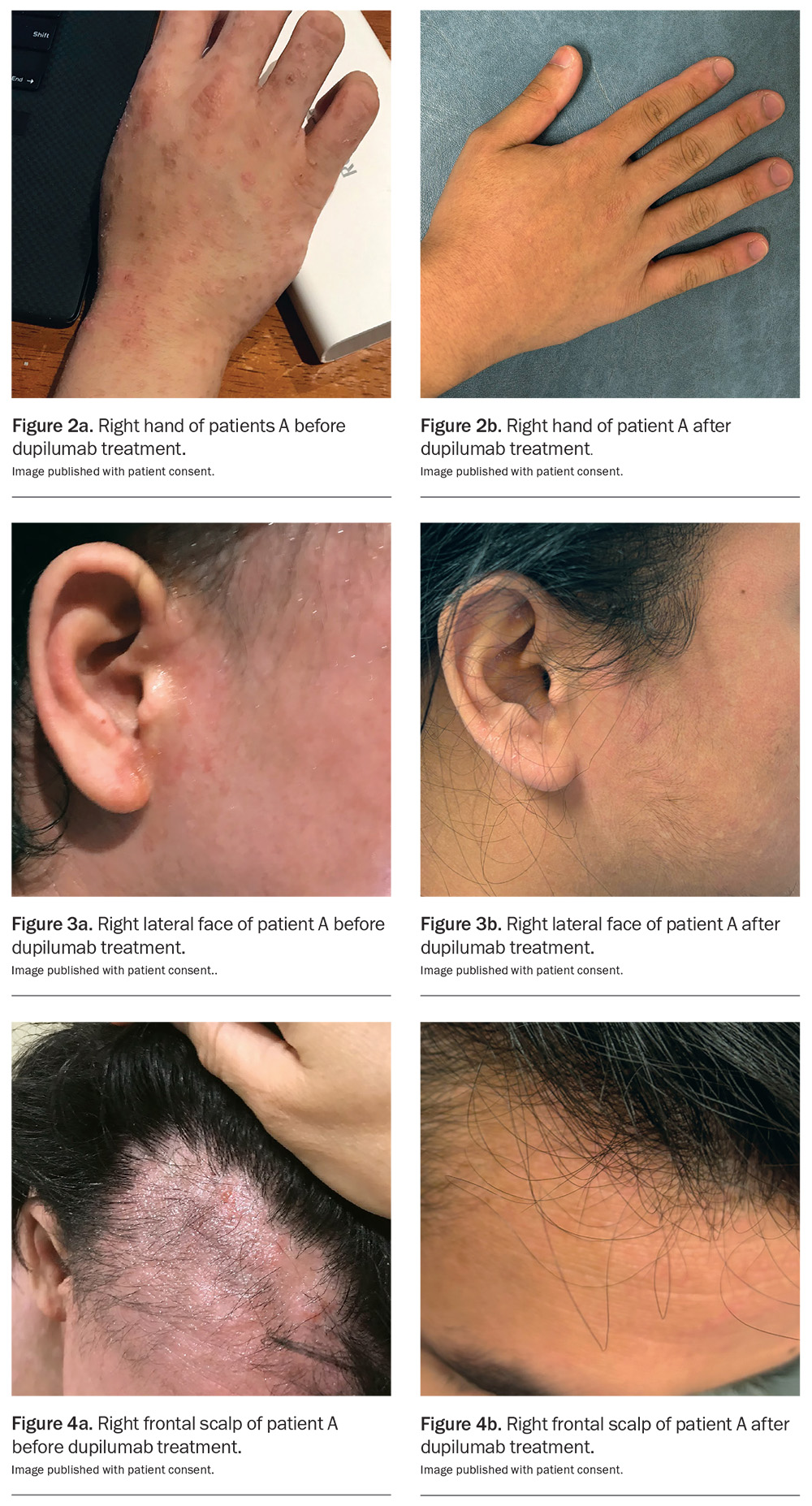

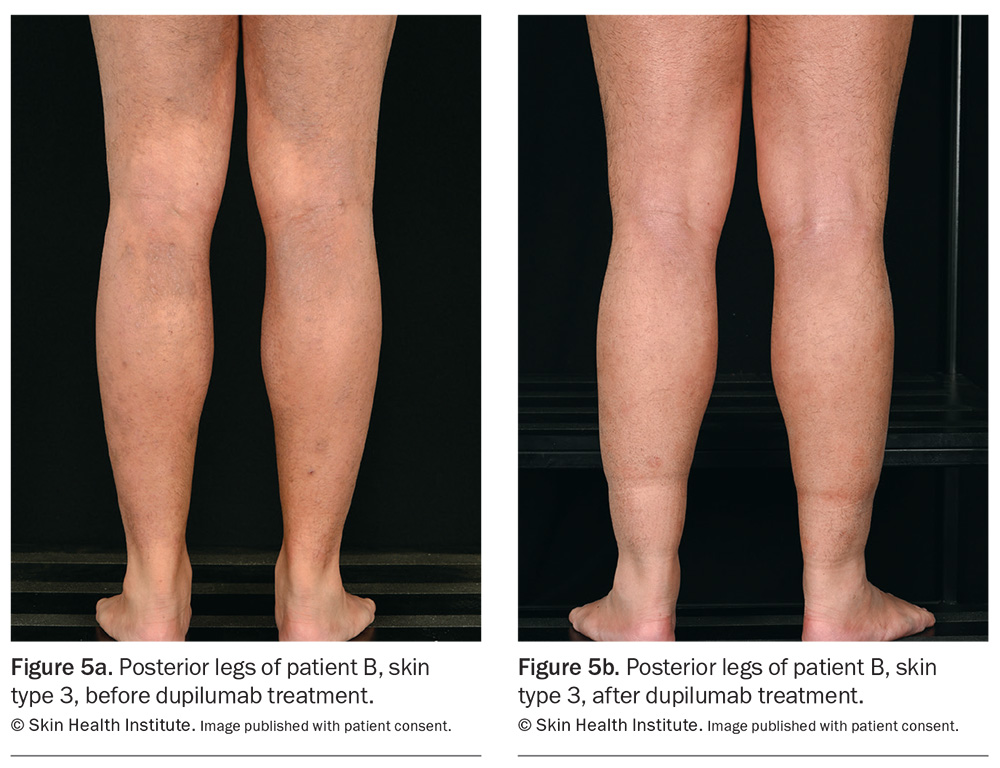

Dupilumab has been listed on the PBS since March 2021 for the treatment of chronic severe AD in patients aged 12 years and older who have failed to respond to optimally prescribed topical treatments. It is approved internationally for use in infants as young as 6 months of age, and real-world data already exist for children.44 Skin areas before and after treatment with dupilumab are shown in Figures 2 to 4 . Similar results appear in Figure 5.

Upadacitinib

Upadacitinib is an oral small molecule that selectively inhibits the signalling of Janus kinase (JAK)-1, which is a key intracellular mediator of Th2 cytokine signalling integral to AD pathogenesis. Upadacitinib has been PBS listed since March 2022 for patients over 12 years of age with chronic severe AD and has been range of inflammatory conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease.46 A head-to-head study comparing the efficacy of upadacitinib with dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe AD showed that upadacitinib was slightly superior to dupilumab. At week 16, 61.6% of patients treated with 30 mg upadacitinib achieved 90% improvement in the EASI (EASI90) versus 40.3% with 300 mg dupilumab.47 Upadacitinib was more rapid at improving itch symptoms compared with dupilumab.46

Upadacitinib is a well-tolerated, convenient, once-daily oral treatment, but requires close monitoring because of its immunosuppressive effect. Side effects include acne, upper respiratory tract infections, headache, gastrointestinal disorders, urinary tract infections and opportunistic infections such as herpes zoster reactivation.48 Haematological abnormalities such as anaemia, thrombocytosis, elevated transaminases and creatine kinase levels and changes in lipid profile have been noted in some patients following the initiation of treatment and require monitoring.

Major serious adverse effects have been described with general JAK inhibition and include cardiovascular events such as venous thromboembolism, stroke and increased risk of malignancy. The TGA has therefore recommended that JAK inhibitors should not be prescribed in patients who are aged over 65 years with a history of cardiovascular disease or at risk of cancer unless there are no alternative treatments. These recommendations are presented as a black box warning in the US, which were triggered by reported outcomes with tofacitinib (a small molecule with nonspecific JAK inhibition [JAK-1, JAK-2, JAK-3 and tyrosine kinase 2] prescribed in rheumatological patients).49 Shingrix and pneumococcal vaccination should be administered to all patients considering treatment with JAK inhibitors.

Emerging topical therapies

Delgocitinib

Delgocitinib is a topical pan-JAK inhibitor for moderate-to-severe hand dermatitis.50 Internationally, it is a 2% formulation, applied twice daily. To date, in Australia, compounding of this agent is unavailable. The medication is expecting TGA approval in late 2025. Pooled analysis of the DELTA 1 and 2 trials (phase 3) showed that 20% and 29% of patients treated with delgocitinib, respectively, achieved treatment success with improved hand eczema severity scores and DLQI scores after 16 weeks compared with 10% and 7% of patients who received the cream vehicle (placebo arm), respectively.51

Tapinarof

Tapinarof 1% is a novel nonsteroidal topical aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) agonist applied once daily, which was originally approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psoriasis. AhR is a cytoplasmic receptor that is ubiquitously expressed, and holds key roles in gene expression, cellular homeostasis and immune responses.52 Its anti-inflammatory effect is mediated by the downregulation of Th2 cytokines, reducing oxidative stress and improving the skin barrier. The phase 3 ADORING trials demonstrated favourable tolerability, safety and efficacy with the use of tapinarof in patients with AD from the age of 2 years. After eight weeks of therapy, an improvement of 75% in EASI (EASI75) was achieved in 56% of patients versus 23% for vehicle.15,53 Common adverse events, although minimal, include folliculitis, headache and nasopharyngitis.

Emerging oral and subcutaneous therapies

Abrocitinib

Abrocitinib is a selective oral JAK 1 inhibitor used for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD. It is TGA approved for moderate-to-severe AD and recently was recommended for a PBS listing (November 2024) for adult patients with chronic severe AD. In a phase 3, double-blind, clinical trial, abrocitinib at a dose of either 200 mg or 100 mg once daily resulted in a significantly improved EASI75 response for moderate-to-severe AD than placebo at weeks 12 and 16, comparable with dupilumab at the study end point.54 However, the 200 mg dose of abrocitinib was superior to dupilumab with respect to itch response at week 2.54 The most commonly reported side effects associated with this treatment included nausea, acne and herpes zoster infection.54

Lebrikizumab

Lebrikizumab is a selective anti IL-13 human monoclonal antibody that is effective for AD particularly because of its slow dissociation rate.55 Lebrikizumab prevents the formation of the IL-13Rα/IL4Rα complex, thus blocking IL-13 signalling (via binding to only the IL-13 α1 chain), which is thought be the key driver of inflammation in AD. Two phase 3 clinical trials have shown that in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD, treatment with lebrikizumab monotherapy every two weeks improved skin clearance compared with placebo over a 16-week induction period.56 An EASI75 response was seen in 58.8% of patients receiving lebrikizumab compared with 16.2% for placebo.57 Most side effects were mild in severity, with conjunctivitis and herpes zoster infections most commonly reported.56,57 Lebrikizumab is TGA approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD in patients 12 years of age and older, but the drug is currently not listed on the PBS (it received a recommendation for a PBS listing in March 2024).

Tralokinumab

Tralokinumab is also a selective anti IL-13 human monoclonal antibody, which is different to lebrikizumab in that it blocks the binding of IL-13 to both receptor chains. Phase 2 studies have shown that tralokinumab was superior to placebo at 16 weeks of treatment and was well tolerated, with most responders not requiring any rescue medication such as topical corticosteroids for the duration of the study.58 Selective IL-13 agents appear to be better tolerated compared with IL-4/-13 inhibitors owing to fewer ocular adverse effects and fewer injection-site reactions.

Nemolizumab

Nemolizumab is an IL-31Rα antagonist that prevents binding of IL-31 to its receptor. IL-31 has been implicated in the pathophysiology of multiple Th2-mediated atopic disorders. Notably, IL-31 has been identified as one of the main drivers of pruritus that characterises AD, exacerbating skin barrier disruption.59 Two replicate phase 3, double-blind, randomised clinical trials (ARCADIA 1 and ARCADIA 2) have demonstrated that nemolizumab 30 mg improved eczema assessment scores, itch and sleep at 16 weeks in adolescent and adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD.60 Generally, the treatment was well tolerated with minimal adverse effects, although those commonly reported were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infections.60 Moreover, there was no increased rates of conjunctivitis, herpes zoster infections or de novo cases of asthma reported.

Rocatinlimab and amlitelimab

The expression of OX40-positive T cells is increased in patients with AD compared with healthy controls. OX40 is present on sensitised T cells after antigen-specific activation, leading to the expression of OX40 on the surface of effector and memory cells, thereby promoting T cell survival and memory.61 It is not expressed in naïve T cells. Moreover, OX40 expression is increased in pathogenic T cells. In skin biopsies of AD lesions, OX40 and OX40 ligand-positive cells were co-localised in the dermis, lending strong support for their role in AD pathogenesis.61,62 The OX40 and OX40 ligand interaction has been reported to enhance cell mobility, promote an effector T cell phenotype, increase cytokine production and conversely, suppress the action of T regulatory cells.63,64

Rocatinlimab is an anti-OX40 monoclonal antibody that binds to OX40 present on an activated CD4-positive, CD8-positive T cell.63 It reduces the number and inhibits the expression of OX40-expressing pathogenic T cells. A phase 2 clinical trial has shown that rocatinlimab treatment improved EASI scores by 60% compared with placebo (15%) over the duration of the study period. The most efficacious response was noted in the group that received 300 mg, fortnightly.65 The most common adverse effects were pyrexia, chills, headache, aphthous ulcers and nausea.65

Amlitelimab is a OX40 ligand monoclonal antibody that binds to the OX40 ligand on antigen-presenting cells. In a phase 2a multicentre study, amlitelimab showed improvements in EASI scores of 80%, compared with 50% in the placebo arm.66 Adverse effects noted with this treatment included headache, hyperhidrosis, pyrexia, iron-deficiency anaemia and elevated aspartate aminotransferase levels.66

Conclusion

AD is a complex, multifactorial disease with a relapsing and remitting course. An improved understanding of the pathogenesis of AD has contributed to an array of novel therapeutics.67 In the era of precision medicine, specific targeted treatments for AD offer promise to patients who have not responded to conventional management. Although some agents are not yet PBS listed in Australia, many are in fact already in use overseas for patients with chronic severe AD with ‘real world’ experience being compiled. This will certainly shed light on the safety and efficacy of these novel therapeutics over years to come. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Goh MSY, Yun JSW, Su JC. Management of atopic dermatitis: a narrative review. Med J Aust 2022; 216: 587-593.

2. Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2020; 396: 345-360.

3. Martin PE, Koplin JJ, Eckert JK, et al. The prevalence and socio-dermographic risk factors of clinical eczema in infancy: a population-based observational study. Clin Exp Allergy 2013; 43:642-651.

4. Bantz SK, Zhu Z, Zheng T. The atopic march: progression from atopic dermatitis to allergic rhinitis and asthma. J Clin Cell Immunol 2014; 5(2): 202.

5. Spergel JM, Paller A. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 112: S118-S127.

6. Tran MM, Lefebvre DL, Dharma C, et al; Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development Study investigators. Predicting the atopic march: results from the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141: 601-607.e8.

7. Schneider L, Hanifin J, Boguniewicz M, et al. Study of the atopic march: development of atopic comorbidities. Pediatr Dermatol 2016; 33: 388-398.

8. Yaghmaie, Pouya, Caroline W. Koudelka, and Eric L. Simpson. Mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131: 428-433.

9. Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 121: 340-347.

10. Silverberg JI, Chiesa-Fuxench Z, Margolis D, et al. Epidemiology and burden of sleep disturbances in atopic dermatitis in US adults. Dermatitis 2022; 33: S104-S113.

11. Keow, S, Abu-Hilal M. Effectiveness of abrocitinib for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in patients switched from dupilumab and/or tralokinumab: a real-world retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2024; 91: 734-735.

12. Miyawaki, K., Nakashima C, Otsuka A. Real-world effectiveness and safety of nemolizumab for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in Japanese patients: a single-centre retrospective study. Eur J Dermatol 2023; 33: 691-692.

13. Olydam JI, Schlösser AR, Custurone P, Nijsten TEC, Hijnen D. Real-world effectiveness of abrocitinib treatment in patients with difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2023; 37: 2537-2542.

14. Nakagawa H, Igarashi A, Saeki H, et al. Safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of delgocitinib ointment in infants with atopic dermatitis: a phase 3, open-label, and long-term study. Allergol Int 2024; 73: 137-142.

15. Silverberg JI, Eichenfield LF, Hebert AA, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily: significant efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults and children down to 2 years of age in the pivotal phase 3 ADORING trials. J Am Acad Dermatol 2024; 91: 457-465.

16. Igarashi A, Tsuji G, Fukasawa S, Murata R, Yamane S. Tapinarof cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: efficacy and safety results from two Japanese phase 3 trials. J Dermatol 2024; 51: 1404-1413.

17. Nakahara T, Kido-Nakahara M, Tsuji G, Furue M. Basics and recent advances in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol 2021; 48: 130-139.

18. Irvine AD, McLean IWH, Leung DYM. Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic disease. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 1315-1327.

19. Leung DYM, Guttman-Yassky E. Deciphering the complexities of atopic dermatitis: shifting paradigms in treatment approaches. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 134: 769-779.

20. Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 70: 338-351.

21. Jones S. Triggers of atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2002; 22: 55-72.

22. Caubet JA, Philippe AE. Allergic triggers in atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2010; 30: 289-307.

23. Ahn, C, Huang W. Clinical Presentation of Atopic Dermatitis. In: Fortson, E., Feldman, S., Strowd, L. (eds) Management of Atopic Dermatitis. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 1027. Springer, Cham, 2017.

24. Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 657-682

25. Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;71: 116-132.

26. Dabade TS, Davis DM, Wetter DA, et al. Wet dressing therapy in conjunction with topical corticosteroids is effective for rapid control of severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: experience with 218 patients over 30 years at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012; 67:100–106.

27. Devillers AC, Oranje AP. Efficacy and safety of ‘wet-wrap’ dressings as an intervention treatment in children with severe and/or refractory atopic dermatitis: a critical review of the literature. Br J Dermatol 2006; 154: 579-585.

28. Majewski S, Bhattacharya T, Asztalos M, et al. Sodium hypochlorite body wash in the management of Staphylococcus aureuscolonized moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Dermatol 2019; 36: 442-447

29. Alexander H, Paller AS, Traidl‐Hoffmann C, et al. The role of bacterial skin infections in atopic dermatitis: expert statement and review from the International Eczema Council Skin Infection Group. Br J Dermatol 2020; 182: 1331‐1342.

30. Mooney E, Rademaker M, Dailey R, et al. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema: Australasian consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol 2015; 56: 241-251.

31. Stacey SK, McEleney M. Topical corticosteroids: choice and application. Am Fam Physician 2021; 103: 337-343.

32. Long CC, Finlay AY. The finger-tip unit--a new practical measure. Clin Exp Dermatol 1991; 16: 444-447.

33. Finnegan P, Murphy M, O’Connor C. #corticophobia: a review on online misinformation related to topical steroids. Clin Exp Dermatol 2023; 48: 112-115.

34. Martins JC, Martins C, Aoki V, et al. Topical tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; (7): CD009864.

35. Sigurgeirsson B, Boznanski A, Todd G, et al. Safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus in atopic dermatitis: a 5-year randomized trial. Pediatric 2015; 135: 597-606.

36. Schlessinger J, Shepard JS, Gower R, et al. Safety, effectiveness, and pharmacokinetics of crisaborole in infants aged 3 to open-label study (CrisADe CARE 1). Am J Clin Dermatol 2020; 21: 272-284.

37. Siegels D, Heratizadeh A, Abraham S, et al. Systemic treatments in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2020; 76: 1053-1076.

38. Halling A, Loft N, Silverberg JI, et al. Real-world evidence of dupilumab efficacy and risk of adverse events: A systematic review and metaanalysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 84: 139-147.

39. Beck, Lisa A, et al. Dupilumab in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a 5-year open-label extension study. JAMA dermatology 2024; 160: 805-812.

40. Jaulent L, Staumont-Sallé D, Tauber M, et al. De novo psoriasis in atopic dermatitis patients treated with dupilumab: a retrospective cohort. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35: e296-e297.

41. Pappa G, Sgouros D, Theodoropoulos K, et al. The IL-4/-13 axis and its blocking in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Clin Med 2022; 11: 5633.

42. Narla S, Silverberg JI, Simpson EL. Management of inadequate response and adverse effects to dupilumab in atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2022; 86: 628-636.

43. Hasan I, Parsons L, Duran S, Zinn Z. Dupilumab therapy for atopic dermatitis is associated with increased risk of cutaneous T cell lymphoma: A retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2024; 91:255-258.

44. Neubauer ZJK, Brunner PM, Geskin LJ, Guttman E, Lipner SR. Decoupling the association of dupilumab with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2024; 91: 1296-1298

45. Rob F, Pinkova B, Sokolova K, Kopuleta J, Jiraskova Zakostelska Z, Cadova J. Real-world efficacy and safety of dupilumab in children with atopic dermatitis under 6 years of age: a retrospective multicentric study. J Dermatolog Treat 2025; 36: 2460578.

46. He H, Guttman-Yassky E. JAK inhibitors for atopic dermatitis: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol 2019; 20: 181-192.

47. Blauvelt A, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib vs dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2021; 157: 1047-1055.

48. Burmester GR, Cohen SB, Winthrop KL, et al. Safety profile of upadacitinib over 15 000 patient-years across rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and atopic dermatitis. RMD Open 2023; 9(1): e002735.

49. Wlassits R, Müller M, Fenzl KH, Lamprecht T, Erlacher L. JAK-Inhibitors – a story of success and adverse events. Open Access Rheumatol 2024; 16: 43-53.

50. Worm M, Bauer A, Elsner P, Mahler V, Molin S, Nielsen TSS. Efficacy and safety of topical delgocitinib in patients with chronic hand eczema: data from a randomized, double‐blind, vehicle‐controlled phase IIa study. Br J Dermatol 2020; 182: 1103-1110.

51. Bissonnette R, Warren RB, Pinter A, et al. Efficacy and safety of delgocitinib cream in adults with moderate to severe chronic hand eczema (DELTA 1 and DELTA 2): results from multicentre, randomised, controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trials. Lancet 2024; 404: 461-473.

52. Furue M, Hashimoto-Hachiya A, Tsuji G. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20: 5424.

53. Igarashi A, Tsuji G, Fukasawa S, Murata R, Yamane S. Tapinarof cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: efficacy and safety results from two Japanese phase 3 trials. J Dermatol 2024; 51: 1404-1413.

54. Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al; JADE COMPARE Investigators. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 1101-1112.

55. Loh, Tiffany Y, Jennifer L. Hsiao, Vivian Y. Shi. Therapeutic potential of lebrikizumab in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Asthma Allergy 2020; 109-114.

56. Blauvelt A, Thyssen JP, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: 52-week results of two randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled phase III trials. Br J Dermatol 2023; 188: 740-748.

57. Silverberg, Jonathan I, et al. Two phase 3 trials of lebrikizumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2023; 388; 12: 1080-1091.

58. Wollenberg A, Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2 study investigators. Tralokinumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from two 52-week, randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2). Br J Dermatol 2021; 184: 437-449.

59. Nakahara T, Furue M. Nemolizumab and atopic dermatitis: the interaction between interleukin-31 and interleukin-31 receptor as a potential therapeutic target for pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis. Curr Treat Options Allergy 5 2018: 405-414.

60. Silverberg, Jonathan I, et al. Nemolizumab with concomitant topical therapy in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (ARCADIA 1 and ARCADIA 2): results from two replicate, double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet 2024; 404: 445-460.

61. Furue M, Mihoko Furue. OX40L–OX40 signaling in atopic dermatitis. J Clin Medicine 2021; 10: 12: 2578.

62. Elsner JS, Carlsson M, Stougaard JK, et al. The OX40 axis is associated with both systemic and local involvement in atopic dermatitis. Acta dermato-venereologica 2020; 100: adv00099.

63. Guttman-Yassky E, Croft M, Geng B, et al. The role of OX40L/OX40 axis signalling in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2024;191: 488-496.

64. Nakagawa H, Iizuka H, Nemoto O, et al. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of repeated intravenous infusions of KHK4083, a fully human anti-OX40 monoclonal antibody, in Japanese patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci 2020; 99: 82-89.

65. Guttman-Yassky, Emma, et al. An anti-OX40 antibody to treat moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b study. The Lancet 2023; 401: 204-214.

66. Weidinger S, Watkins T, Carr A, et al. 520-Evaluating the expression of OX40 and OX40 ligand in lesional skin versus non-lesional skin in volunteers with atopic dermatitis and in healthy control skin. Br J Dermatol 2024; 190(Suppl): ii22-ii23.

67. Facheris P, Jeffery J, Del Duca E, Guttman-Yassky E. The translational revolution in atopic dermatitis: the paradigm shift from pathogenesis to treatment. Cell Mol Immunol 2023; 20: 448-474.