The use of topical corticosteroids for inflammatory dermatoses

Topical corticosteroids have been a cornerstone in the management of inflammatory dermatoses for decades, offering potent anti-inflammatory effects while minimising the risk of the systemic adverse effects of oral corticosteroids. Carefully selecting the optimal preparation is crucial to maximise treatment efficacy and reduce complications.

- Topical corticosteroids are highly effective in treating a wide range of inflammatory dermatoses because of their anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive and antiproliferative effects.

- The potency and vehicle of a topical corticosteroid significantly affect its clinical efficacy, with various formulations offering different advantages depending on the severity of the condition and the area of skin involved.

- Misconceptions and fears about the safety of topical corticosteroids can lead to underuse and inadequate treatment, whereas inappropriate use may cause side effects; therefore, patient education is essential.

- Proper application techniques, including using the finger-tip unit system to guide dosing and combining topical corticosteroids with emollients, can improve treatment outcomes, and occlusion therapy may enhance effectiveness in severe or resistant cases.

- Nonsteroidal treatments, such as topical calcineurin inhibitors, phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors and Janus kinase inhibitors, may be suitable alternatives in certain cases, although cost and availability can be limiting factors.

Topical corticosteroids (TCS) are used widely to treat a range of inflammatory dermatoses, including atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus, immunobullous disorders, morphoea, vitiligo, cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and dermatomyositis.1,2 Their anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive and antiproliferative effects make them highly effective in managing these conditions.3 Despite their efficacy, misconceptions about TCS use and safety among patients and healthcare providers can lead to inadequate treatment, whereas inappropriate use of TCS may result in unwanted side effects.1,3 Corticosteroid phobia remains a major obstacle to effective treatment.4 Understanding how to select an appropriate TCS preparation is key to optimising patient outcomes.1

This article explores the key factors to consider when selecting a TCS preparation, examines the role of different TCS vehicles and potencies, and discusses TCS safety. It also identifies potential complications associated with prolonged or improper TCS use and discusses alternative, localised treatment options.

Mechanism of action of TCS

TCS exert anti-inflammatory properties, similar to oral corticosteroids, but are delivered in a localised manner. When applied locally, they can effectively reduce inflammation, pruritus and oedema at the site of application, without the systemic side effects associated with oral corticosteroids, such as osteoporosis, weight gain, hypertension and hyperglycaemia.3,5 TCS exert their anti-inflammatory effects through multiple actions by:

- inducing vasoconstriction, which reduces the delivery of inflammatory mediators to the affected area

- inhibiting phospholipase A2, leading to decreased production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes

- stabilising lysozymes in neutrophils, preventing degranulation, thereby limiting inflammation2,6,7

- altering gene transcription, thereby increasing the expression of anti-inflammatory genes

- reducing the expression of cytokines and other mediators involved in the aberrant inflammatory response.2,6,7

TCS also have an antimitotic effect that is thought to be particularly beneficial in patients with psoriasis.8,9

Selecting an appropriate TCS

When selecting a TCS preparation, various factors should be considered, including: potency of TCS and choice of vehicle; disease site and severity; and patient characteristics, such as age.3,10

TCS potency

The potency of a drug describes the amount of drug required to produce the desired therapeutic effect.2 The potency of a TCS depends on its specific molecular structure (e.g. betamethasone valerate or dipropionate), formulation (cream, ointment or solution), and the extent of transdermal absorption.1

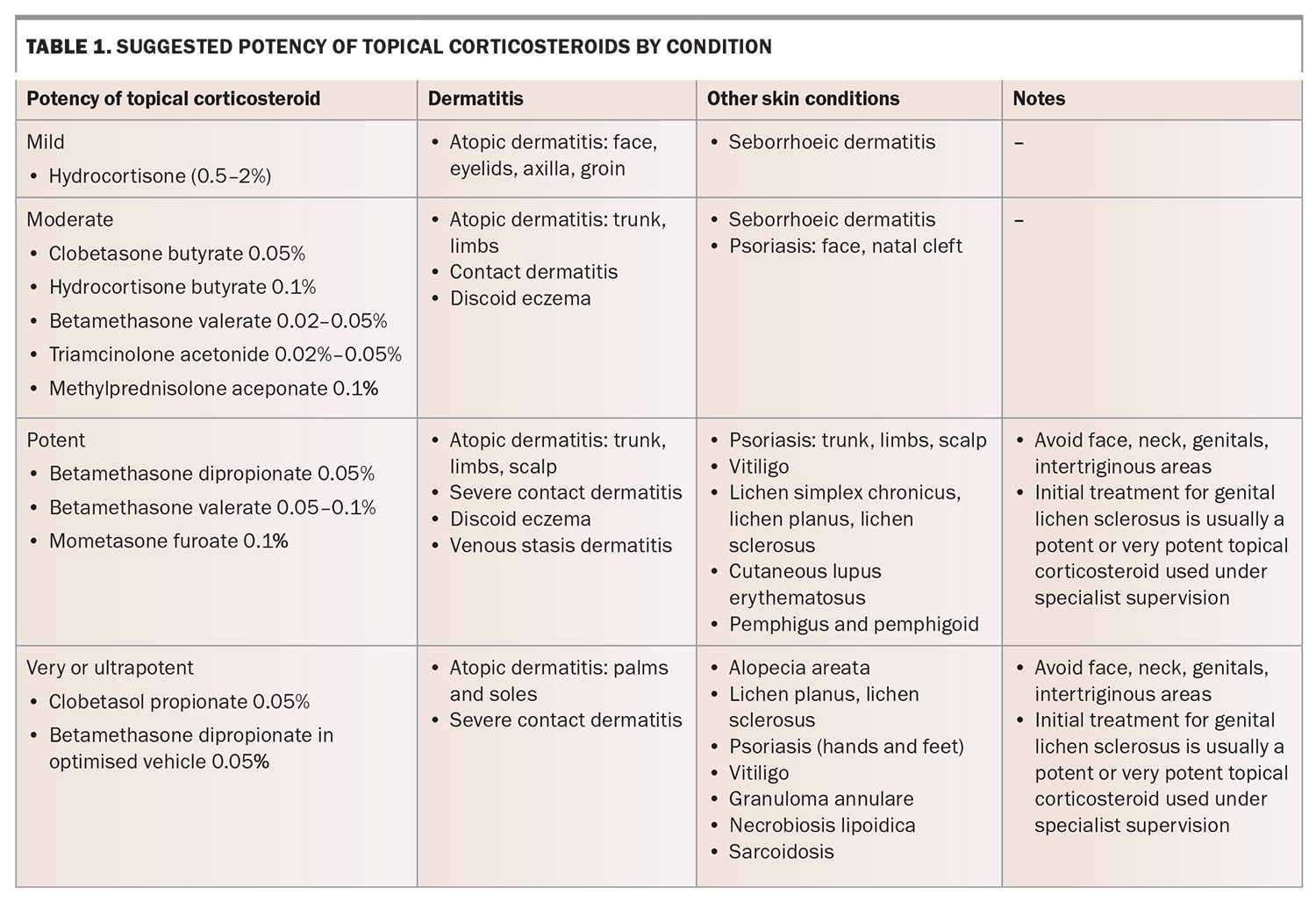

TCS are categorised based on potency, ranging from mild (e.g. hydrocortisone 1%) to very potent (e.g. clobetasol propionate 0.05%).11 TCS cannot be diluted as their potency does not significantly depend on concentration.12 Potency is reduced by choosing a less potent corticosteroid and therefore the relative potencies of different molecules need to be committed to memory.11 Ideally, clinicians should select the least potent TCS that will effectively treat the condition, considering disease site, disease severity and patient characteristics (Table 1). The penetration of TCS is increased in disease states of inflammation and desquamation because of skin barrier disruption.13,14

Vehicle choice

When delivering a TCS preparation, the active steroid is carried by a vehicle or a carrier (e.g. a cream or ointment base).15 The vehicle can affect TCS bioavailability by their interaction with the skin and by changing the characteristics of the steroid.15 TCS are available in various formulations, including ointments, creams, lotions, gels, foams and shampoos.16,17

- Ointments: these are mostly composed of a petroleum base, which provides superior occlusion, enhancing absorption and efficacy. Ointments are particularly useful for dry, hyperkeratotic lesions, and are effective as barrier moisturisers because they remain on the skin surface and prevent moisture loss. Less preservative is required, reducing the risk of contact allergy. However, ointments are greasy, and the degree of occlusion may increase the risk of folliculitis and heat rash.13

- Creams: these are composed of more equal proportions of water and oil, and tend to be easily absorbed. Creams leave less residue on the skin surface and may be preferable for areas with hair or acute exudative inflammation. Creams may contain preservatives or alcohol that may sting or cause irritant or allergic contact dermatitis.18

- Lotions: these contain a higher proportion of water and are useful for hairy areas, such as the scalp, as they are nonocclusive. Lotions can contain alcohol that may sting inflamed skin and cause irritation, as previously discussed, and may also have a drying effect on the skin.19

- Gels: these are aqueous, rapidly absorbed and nongreasy.10

- Foams: these preparations of TCS offer cosmetic and pharmacodynamic advantages over cream and ointment vehicles. Foams are highly effective for steroid delivery and are associated with excellent patient compliance with treatment.20

- Shampoos: those containing clobetasol propionate 0.05% are safe and effective for use in scalp psoriasis.17

Underlying skin disease

Some dermatoses, such as those outlined below, require a high-potency TCS.

- Oral lichen planus: TCS cream or ointment may be used safely and effectively inside the oral cavity.21 High-potency TCS may be required, especially for erosive or atrophic oral lichen planus.21 Oral candidiasis may be a complication of oral TCS use, and nystatin drops or amphotericin lozenges may be required.21 Intralesional corticosteroid injections may also be effective.22

- Lichen sclerosus: first-line treatment is a potent or ultrapotent TCS, even in the genital region. In most cases, the potency can be reduced for maintenance treatment.23 This treatment appears to be safe and effective long term and improves quality of life.24

- Vitiligo: may require potent or ultrapotent TCS for effective treatment.25

- Bullous pemphigoid: localised disease may be managed with a potent TCS.25

- Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: may require a more potent TCS.25

Severity and disease site

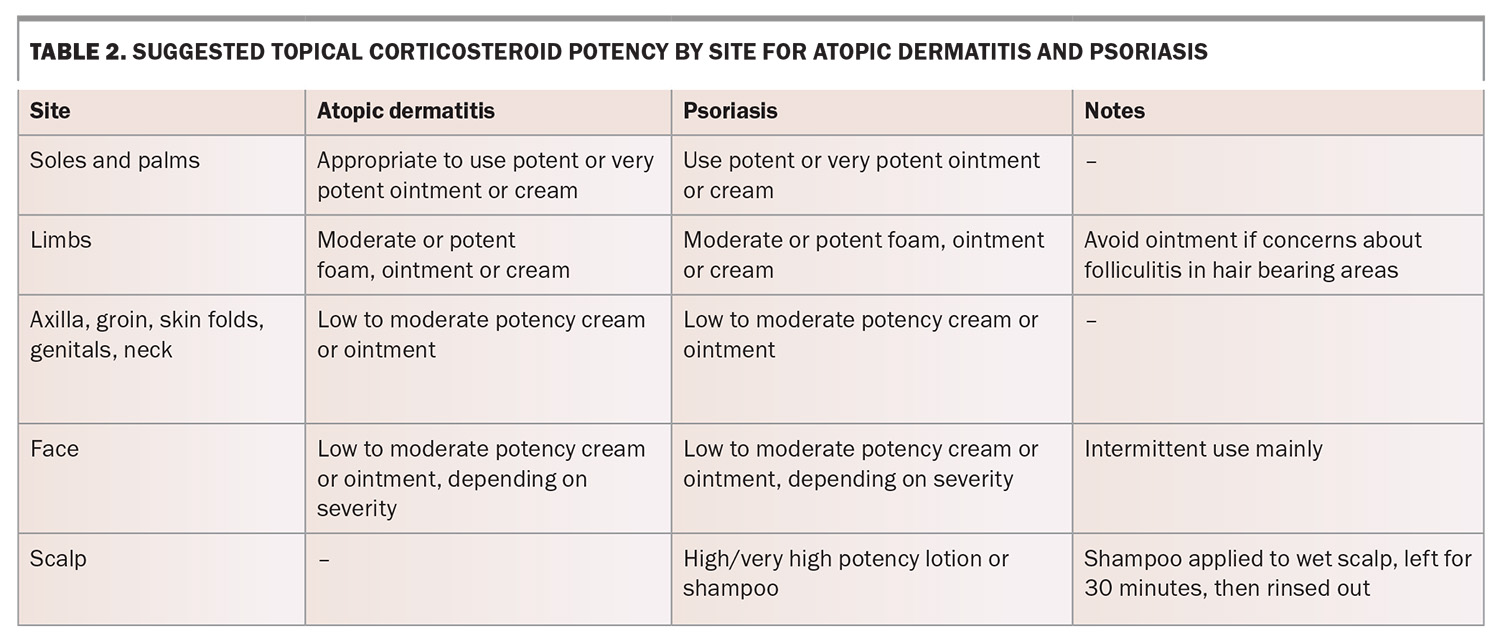

The recommended potency of TCS depends on the severity and disease site (Table 2). Areas such as the face, genitals and intertriginous regions (e.g. axilla, groin) are more prone to localised adverse effects, particularly with prolonged use of potent corticosteroids, and care should be taken when addressing inflammatory dermatoses in these areas. Low-potency TCS are recommended for these areas if required to minimise localised adverse effects.2,26

- Palms and soles: inflammation in thicker skin areas such as the palms and soles (with a thicker stratum corneum) may require higher-potency TCS, such as clobetasol propionate, for effective penetration.2,26

- Eyelids: low-potency TCS, such as hydrocortisone 1%, appear to be safe for use in eyelid dermatitis. There is no evidence that periorbital application of weak TCS result in ocular complications such as glaucoma.27

- Face: high-potency TCS should be avoided on the face to avoid periorificial dermatitis.28

Combination of TCS products

Combination products consisting of a TCS combined with another active ingredient, such as an antibiotic, anti-fungal or calcipotriol, are also available and may be prescribed for specific indications.12 The combination of betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% with calcipotriol appears to be more effective for psoriasis than either product alone. However, in general, the use of combination products is not considered best practice, except for the combination of 1% hydrocortisone and an antifungal product, which may be useful to treat dermatoses in the intertriginous zones where Candida colonisation can be a cofactor in inflammation.

Proper application of TCS

Dosage and frequency

TCS are usually used once to twice daily.11 There may be no therapeutic benefit in applying TCS more than once daily after the first few days of application, although the risk of complications might be increased.29 Emollients are recommended in combination with TCS because they have greater efficacy when used together compared with TCS alone.30 Treatment should be continued until active inflammation is resolved to minimise the likelihood of rebound recurrence and exacerbation of disease.31,32 As TCS are generally used for chronic-relapsing cutaneous dermatoses, intermittent treatment may be required for flares.33

There is no requirement to use TCS sparingly. This word is often printed on medication labels by pharmacists even when not written on the prescription. An adequate amount of TCS should be applied to cover the affected area.11 The traditional guidance to ‘apply thinly’ or ‘use sparingly’ may contribute to steroid phobia, fuelled by misinformation on social media platforms, potentially leading to inadequate treatment.34

Finger-tip unit

Judicious use of TCS is the key to maximise the efficacy of treatment and minimise the risk of adverse effects. The finger-tip unit (FTU) system was proposed in 1991 to simply quantify TCS use.35 One FTU refers to the amount of cream squeezed out of its tube onto the finger pad of the terminal phalanx of the index finger (from the tip to the skin fold overlying the palmar aspect of the distal interphalangeal joint). This equates to approximately 0.4 g in an adult woman, 0.5 g in an adult man and less in children.35

The recommended FTUs per body site are as follows:

- one palm: 0.5 FTU

- face and neck: 2.5 FTUs

- one arm: 3 FTUs

- one leg: 6 FTUs

- trunk (front and back): 14 FTUs

- entire body: about 40 FTUs.

Occlusion therapy

TCS may be applied under occlusion with a tubular bandage or plastic wrap to enhance penetration in severe or recalcitrant lesions. However, chronic use of large quantities of potent TCS used under occlusion over large surface areas can theoretically lead to systemic absorption and localised adverse reactions at the site of application.1,26,32,36

Complications and relative safety of TCS use

It is essential to educate patients about appropriate use of TCS. Although systemic absorption is rare, prolonged, inappropriate, use of high-potency TCS over large surface areas or under occlusion may lead to hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis suppression and Cushing’s syndrome.37

Localised adverse effects of TCS may occur in situations where TCS are used for long periods for an inappropriate condition or site. These include:

- skin atrophy

- striae

- easy bruising

- acne

- rosacea

- periorificial dermatitis

- ocular complications (periocular dermatitis, glaucoma and cataracts, when applied to the eyelids)

- hypertrichosis

- masking of fungal infections.1,3

As with medications in general, it is the inappropriate use of TCS that leads to complications. If TCS are used at the right potency for the site, severity and condition being treated, they are outstandingly safe.38 They remain the mainstay of treatment for mild atopic dermatitis and many other conditions.

Nonsteroidal treatments for cutaneous dermatoses

For patients who require long-term management of cutaneous inflammation, experience adverse effects or prefer nonsteroidal treatments, several treatments are available, as outlined below.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors

Topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus may be used as steroid-sparing agents for sensitive areas such as the face and eyelids. These are immunosuppressant treatments that suppress T-cell activation and cytokine release.26 Pimecrolimus 1% cream is PBS listed for treating facial and eyelid atopic dermatitis in adults and children who are at least 3 months of age, when TCS are contraindicated or fail to control the disease with intermittent use. Tacrolimus is more potent that pimecrolimus, is not PBS listed and needs to be compounded.

Topical phosphodiesterase type-4 inhibitors

Crisaborole 2% ointment is a topical phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor that is TGA approved for mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis in patients aged 2 years and older, but is not PBS listed. It has been shown to be well tolerated in clinical trials; however, cost may be a barrier.39

Topical Janus kinase inhibitors

The Janus kinase signalling pathways are key downstream mediators of inflammatory dermatoses and are an emerging target for the topical treatment of cutaneous disease. Several studies show significant promise for the use of Janus kinase inhibitors, including delgocitinib and ruxolitinib, as topical treatment for several inflammatory conditions, such as atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata and vitiligo.40 As with phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors, cost and availability are barriers. These are currently not commercially compounded in Australia.

Intralesional corticosteroids

For localised, recalcitrant lesions, such as thick psoriatic plaques, prurigo nodularis or keloid scars, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections may be useful.41

Conclusion

TCS remain the mainstay of treatment for inflammatory dermatoses because of their efficacy and rapid onset of action. However, appropriate selection of potency, vehicle and duration of use is crucial to minimise complications. Clinicians should be aware of site-specific risks, educate patients on proper application techniques and consider alternative therapies if needed. Ideally, clinicians should select the weakest possible TCS that will treat the condition; however, it is important to avoid using a subtherapeutic dose for the condition being treated. Balancing efficacy with safety through judicious TCS use and adjunctive treatments optimises long-term patient outcomes while mitigating risks associated with steroid overuse or misuse. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Iyengar, Dr Larney, Dr Punchihewa and Associate Professor Shumack: None. Associate Professor Foley has received research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, UCB Pharma; consulting fees from Apogee, Aslan, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, GenesisCare, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Mayne Pharma, MedImmune, Novartis, Oruka, Pfizer, UCB Pharma, payment or honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi, Sun Pharma and UCB Pharma, payment for expert testimony from Pfizer, and participated on an Advisory Board for AbbVie, Amgen, Aslan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Mayne Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sun Pharma and UCB Pharma.

References

1. Aung T, Aung ST. Selection of an effective topical corticosteroid. Aust J Gen Pract 2021; 50: 651-655.

2. Gabros S, Nessel TA, Zito PM. Topical Corticosteroids. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532940/ (accessed May 2025).

3. Mooney E, Rademaker M, Dailey R, et al. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema: Australasian consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol 2015; 56: 241-251.

4. Finnegan P, Murphy M, O’Connor C. #corticophobia: a review on online misinformation related to topical steroids. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 2023; 48: 112-115.

5. Yasir M, Goyal A, Sonthalia S. Corticosteroid Adverse Effects. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

6. Ahluwalia A. Topical glucocorticoids and the skin--mechanisms of action: an update. Mediators Inflamm 1998; 7: 183-193.

7. Abraham A, Roga G. Topical steroid-damaged skin. Indian J Dermatol 2014; 59: 456-459.

8. Uva L, Miguel D, Pinheiro C, et al. Mechanisms of action of topical corticosteroids in psoriasis. Int J Endocrinol 2012; 2012: 561018.

9. Mason AR, Mason J, Cork M, et al. Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(3): CD005028.

10. Stacey SK, McEleney M. Topical corticosteroids: choice and application. Am Fam Physician 2021; 103: 337-343.

11. The Australasian College of Dermatologists. The Australasian College of Dermatologists consensus statement: topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema. Rhodes, NSW: ACD, 2017. Available online at: www.dermcoll.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/ACD-Consensus-Statement-Topical-Corticosteroids-and-Eczema-Feb-2017.pdf (accessed May 2025).

12. Oakley A. Topical steroids. Dermnet.nz. Available at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/topical-steroid (accessed May 2025).

13. Ference JD, Last AR. Choosing topical corticosteroids. Am Fam Physician 2009; 79: 135-140

14. Tadicherla S, Ross K, Shenefelt PD, Fenske NA. Topical corticosteroids in dermatology. J Drugs Dermatol 2009; 8: 1093-1105.

15. Oakley R, Arents BWM, Lawton S, et al. Topical corticosteroid vehicle composition and implications for clinical practice. Clin Exp Dermatol 2021; 46: 259-69.

16. Lee NP, Arriola ER. Topical corticosteroids: back to basics. West J Med 1999; 171: 351-353

17. Papp K, Poulin Y, Barber K, Lynde C, et al. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of clobetasol propionate shampoo (CPS) maintenance in patients with moderate scalp psoriasis: a Pan-European analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012; 26: 1407-1414.

18. Coloe J, Zirwas MJ. Allergens in corticosteroid vehicles. Dermatitis 2008; 19: 38-42.

19. Lyon CC, Smith AJ, Griffiths CE, Beck MH. Peristomal dermatoses: a novel indication for topical steroid lotions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 43: 679-682.

20. Lebwohl M, Sherer D, Washenik K, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of clobetasol propionate 0.05% foam in the treatment of nonscalp psoriasis. Int J Dermatol 2002; 41: 269-274.

21. Zheng T, Liu C, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical clobetasol propionate in comparison with alternative treatments in oral lichen planus: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024; 11: 1391754.

22. Aliyah A, Noura S, Maryam M, et al. Intralesional corticosteroid injections for the treatment of oral lichen planus: a systematic review. JDDS 24: 74-80.

23. Yeon J, Oakley A, Olsson A, Drummond C, et al. Vulval lichen sclerosus: An Australasian management consensus. Australas J Dermatol 2021; 62: 292-99.

24. De Luca DA, Papara C, Vorobyev A, Staiger H et al. Lichen sclerosus: The 2023 update. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023; 10: 1106318.

25. Das A, Panda S. Use of topical corticosteroids in dermatology: an evidence-based approach. Indian J Dermatol 2017; 62: 237-250.

26. Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71: 116-132.

27. Daniel BS, Orchard D. Ocular side-effects of topical corticosteroids: what a dermatologist needs to know. Australas J Dermatol 2015; 56: 164-169.

28. Ross G. Treatments for atopic dermatitis. Aust Prescr 2023; 46: 9-12.

29. Williams HC. Established corticosteroid creams should be applied only once daily in patients with atopic eczema. BMJ 2007; 334: 1272.

30. Van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Christensen R, et al. Emollients and moisturisers for eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; (2): CD012119.

31. Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 657-82.

32. Goh MS, Yun JS, Su JC. Management of atopic dermatitis: a narrative review. Med J Aust 2022; 216: 587-593.

33. Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis. Section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71: 1218-1233.

34. Tan SY, Chandran NS, Choi EC. Steroid phobia: is there a basis? A review of topical steroid safety, addiction and withdrawal. Clin Drug Investig. 2021; 41: 835-842.

35. Long CC, Finlay AY. The finger-tip unit – a new practical measure. Clin Exp Dermatol 1991; 16: 444-447.

36. González-López G, Ceballos-Rodríguez RM, González-López JJ. Efficacy and safety of wet wrap therapy for patients with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177: 688-695.

37. Coondoo A, Phiske M, Verma S, Lahiri K. Side-effects of topical steroids: a long overdue revisit. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014; 5: 416-425.

38. Hong E, Smith S, Fischer G. Evaluation of the atrophogenic potential of topical corticosteroids in pediatric dermatology patients. Pediatr Dermatol 2011; 28: 393-396.

39. Yang H, Li P, Shu H, et al. Efficacy and safety of proactive therapy with 2% crisaborole ointment in children with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled study. Paediatr Drugs 2025; 27: 367-376.

40. Tavoletti G, Avallone G, Conforti C, et al. Topical ruxolitinib: a new treatment for vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2023; 37: 2222-2230.

41. Richards RN. Update on intralesional steroid: focus on dermatoses. J Cutan Med Surg 2010; 14: 19-23.