Popliteal artery aneurysms

Popliteal artery aneurysms are rare but are associated with increased mortality and limb loss once patients become symptomatic. Surgical intervention is considered for medically fit patients with a popliteal artery aneurysm when the artery reaches at least 20 mm in diameter.

Apopliteal aneurysm is defined as a popliteal artery that is at least 1.5 times the diameter of the proximal segment of the same vessel.1 However, as the entire arterial system is often enlarged a comparison between one segment and another may not be helpful; the most common size of popliteal artery is between 5 and 11 mm in diameter based on sex and body size so theoretically even an 8 mm popliteal artery could be considered aneurysmal in some people.2,3 According to most authors, the popliteal artery should be a minimum of 12 mm in diameter to qualify as an aneurysm. In other words the popliteal artery should be at least 50% larger than the healthy one and at least 12 mm in diameter (Figure 1).

There is also a difference between a false and a true aneurysm. False aneurysms are less common than true aneurysms and are most likely to be a consequence of trauma or iatrogenic injury. In these individuals, the enlarged segment of the vessel does not contain all the arterial layers that are present in true aneurysms.

Natural history

About 40% of patients will present with bilateral popliteal artery aneurysms. Popliteal artery aneurysms, unlike abdominal aortic aneurysms, tend to thrombose or embolise rather than rupture. Almost two-thirds of patients with popliteal artery aneurysms become symptomatic within five years of diagnosis. About one-third develop a thromboembolic complication or the aneurysm compresses surrounding structures such as the popliteal vein.4 The risk of limb loss is quite significant and major amputation has been reported in 14% of patients with popliteal artery aneurysms in a large systematic review of almost 900 patients.5 The risk of complications increase over time.6

Risk factors

Risk factors for popliteal artery aneurysms are similar to those seen in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Risk factors include:

- age

- male sex

- hypertension

- smoking.

Recognising a popliteal artery aneurysm

About 40% of patients with a popliteal artery aneurysm will also present with a simultaneous abdominal aortic aneurysm (Figure 1).4 Patients can develop acute limb-threatening ischaemia due to a sudden thrombosis of the popliteal artery but more often patients present with chronic symptoms. These include claudication pain, pain at rest or tissue loss caused by chronic obstruction of the arterial system of the leg as a result of embolisation and atherosclerotic progression.7 Embolic events or atherosclerotic progression can also lead to stenosis or occlusion of the tibial arteries below the aneurysm. Blue toe syndrome, a typical sign of an embolism, could also potentially be due to a popliteal artery aneurysm although atherosclerotic plaques are often the culprit.

Is the size of the aneurysm clinically relevant?

The risk of rupture with abdominal aortic aneurysms rises with increasing size but is this true for the most common complication of popliteal artery aneurysms – thrombosis of the artery? The size of the aneurysm increases over time – at a rate of between 0.7 and 3.7 mm per year according to some experts, based on the initial diameter (the larger the popliteal artery aneurysm the faster the growth). Interestingly, thromboembolic episodes do not particularly correlate with size.8,9 Larger popliteal artery aneurysms tend to cause local compression and the risk of rupture is small even in the largest popliteal artery aneurysms – between 0.1 and 2.8%.10 Abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture rates are much higher.11

Diagnosing popliteal artery aneurysms

As previously discussed, popliteal artery aneurysms should be excluded in patients with acute or chronic limb-threatening ischaemia. Many patients with a popliteal artery aneurysm will have an expansile popliteal pulse. However, clinical examination is not very reliable and imaging is necessary, not only to verify the suspected diagnosis, but also to establish a plan for surgical management.12 Duplex ultrasound is sensitive enough, readily available, non-invasive and reliable. It can also help describe the size, location and blood flow details of the popliteal artery.13 A CT or MRI angiogram can give us a precise anatomy of the aneurysm, providing characteristics of the vessel wall and burden of the thrombus (Figure 2). Surgical reconstruction can be reliably planned based on this information. The disadvantage of CT is its radiation exposure; MRI on the other hand is more expensive.

Digital subtraction angiography is not a method of choice for diagnosing popliteal artery aneurysms and should not be used as a first choice. It is invasive, can underestimate the size of the popliteal aneurysm and also carries the risk of radiation exposure and iatrogenic injury. Digital subtraction angiography is reserved for endovascular treatments (Figure 3).

Surgery to treat popliteal artery aneurysms

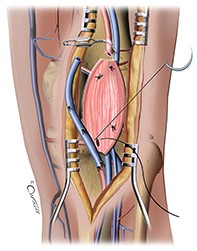

The aim of surgery is to exclude the aneurysm from the circulation while maintaining patency of the arteries supplying the leg and foot. This can be achieved using either open surgery or endovascular (key-hole) surgery to repair the artery (Figure 4). Results of surgical treatment for popliteal artery aneurysms are best when the aneurysm is asymptomatic.14 Even though some authors recommend surveillance only for small aneurysms, there is a general consensus among surgeons that medically fit patients should be offered intervention if they:15

- have an aneurysm that exceeds 20 mm in size

- are symptomatic, given the fact that critical limb ischaemia caused by thrombosis carries a high risk of morbidity and mortality.16

High-risk patients, bed-bound patients and patients with dementia may be treated conservatively, even if they have larger-size aneurysms.

Open surgery repair

Open surgical resection of the aneurysm with bypass or interpositioning using either a synthetic or autologous graft has been widely reported with good outcomes. Patency of these grafts is reported to be between 74 and 94% and mortality associated with the procedure is less than 1%.17

Endovascular repair

Endovascular stenting is a more recent intervention that is associated with very good outcomes in patients who have a popliteal artery aneurysm without thrombosis. In general, the primary and secondary patency rates of popliteal artery endografts have been reported to be between 86 and 91% at two years.18 Patients who underwent endovascular stenting also had shorter operating times and a shorter hospital stay compared with patients undergoing open surgery, whereas patency rates were similar between the two groups.19 Similar results have been reported by other groups.20

In acute settings where the popliteal artery aneurysm is thrombosed and causes acute limb-threatening ischaemia, outcomes using endovascular repair are much worse and the rate of major amputation is 13 to 14%, even if the repair is attempted.21,22 The long-term outcomes of endovascular repair are not known. There are some suggestions that patients with limited vessel run-off (partially thrombosed tibial arteries) and those who often bend their knees (perhaps more active people) should still have an open repair rather than an endovascular one.18,23

Conclusion

Popliteal artery aneurysms are rare but are associated with increased mortality and limb loss once patients become symptomatic. Most patients will become symptomatic in their life-time. The common symptoms are chronic limb claudication or a thromboembolic event that results in ulcers or pain at rest. However, open surgical treatment is reliable and has good outcomes, including low mortality. Endovascular (key-hole) repair is also available for selected patients. MT